Building a Collection #84

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77

By Johannes Brahms

____________

“It is a real pleasure to see music so bright and spontaneous expressed with corresponding ease and grace.”

-Johannes Brahms

We encounter Johannes Brahms for the fifth time on our survey, this time with his Violin Concerto in D major, certainly one of the great violin concertos ever composed and still one of the most frequently performed and recorded. Let’s take a closer look at how the concerto came to fruition.

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms (b. 1833 – d. 1897) was a German composer of the Romantic era and is generally regarded to be one of the greatest composers ever. Even though Brahms was from the Romantic era, he was very much connected to the Classical forms as seen in the works of Haydn, Mozart, and especially Beethoven. In that sense, Brahms represented a “conservative” approach to musical tradition at a time when form and convention were changing due to Wagner and others. Brahms wrote symphonies and other orchestral works, chamber music, concertos, keyboard works, vocal, and choral music.

Brahms was from a musical family in Hamburg and showed a great deal of promise even at a young age. He began as a pianist and would often perform around Hamburg in eating and drinking establishments. By adulthood, Brahms had become friends with well-known musicians of the time. He befriended the violinist Joseph Joachim, a relationship that would be personally and artistically important throughout his life. But perhaps most important was his friendship with the famous composer Robert Schumann. Schumann, twenty-two years older than Brahms, became his most fervent advocate. Brahms likewise had tremendous esteem for Schumann. Brahms practically became a member of Schumann’s family, and after Schumann’s death at the too young age of 46, Brahms continued to be close friends with his widow, the pianist and composer Clara Schumann. Brahms never married, although he apparently had several romantic relationships throughout his life. There is speculation about whether Brahms and Clara were more than friends, and there is evidence that Brahms was probably in love with her.

Many of Brahms’ compositions have become universally known, and many are perennial favorites that are frequently programmed by orchestras around the world. As part of the “Big 3” of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, he occupies a central place in the history of classical music. My personal favorites by Brahms include his Symphony no. 1, Symphony no. 4, Ein Deutsches Requiem, Piano Concerto no. 1, Violin Concerto, Haydn Variations, and his Piano Trio no. 1.

Violin Concerto in D major

Brahms finished his only Violin Concerto in D major in 1878 and dedicated it to his good friend and violinist Joseph Joachim. Joachim would later include Brahms’ concerto among the four greatest German violin concertos, joining the concertos of Beethoven, Bruch, and Mendelssohn. The premiere was given on New Year’s Day 1879 with Joachim as the soloist in Leipzig with Brahms conducting, and with Joachim insisting on playing the Beethoven concerto (also in D major) first, followed by the Brahms. Reception was lukewarm, with famous conductor Hans von Bülow reportedly declaring it a concerto “against the violin”. Later the violin prodigy Bronislaw Huberman would loudly disagree, proclaiming it “for violin against orchestra — and the violin wins.” After the concerto was played for the first time in Vienna shortly thereafter with Joseph Hellmesberger as soloist,it was received warmly. Still, the concerto divided opinion, with virtuosos Henryk Wieniawski and Pablo de Sarasate making critical comments about it. It took time for the concerto to gain a foothold, but it certainly did. Modern listeners see the concerto through a different historical lens of course and can more readily understand what Brahms was creating. There can be no doubt Brahms was paying homage to Beethoven in the key chosen as well as some other similarities but of course being written some 72 years later means it occupies a very different sound world than the Beethoven concerto.

While the concerto was originally planned in four movements, Brahms was unhappy with one of the middle movements and so removed it. Indeed, so uncomfortable was Brahms in composing a concerto for the violin (he was a pianist), that he turned to Joachim for advice. The concerto in its final version follows a traditional concerto form in three movements, in the typical faster-slower-faster sequence. The movements are as follows:

Allegro non troppo

Adagio

Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace — Poco più presto

Jan Swafford in program notes for the Boston Symphony comments:

“As much as anything he wrote, the Violin Concerto demonstrates Brahms’s singular mingling of tradition and innovation. In theory his model for a first movement of a concerto is Mozart’s: the orchestra plays the first exposition alone, introducing the basic material, then the soloist enters and begins a second exposition that roughly follows the first, with new material from the soloist. But Brahms’s second exposition is quite altered from the first, and the entry of the soloist changes the equation drastically.

The movement is enormous, longer than the other two put together. It begins quietly, strings and low winds presenting a D major theme that sounds like a distant horn call. At a magical change to C major the oboe sings a lyrical theme over pulsating strings. The first exposition largely unfolds as a calm and lovely expanse. Then a note of tension intrudes, ushering in the soloist with a D minor explosion of boldness and fury. The soloist takes over the music for a moment, like a little cadenza. From there on the second exposition, in contrast to the first, is a dialectic between peace and unrest.

Much of the time the violin plays rippling figures over the orchestra’s melodies, but none of the themes is very sustained until the end of the exposition, when the violin falls into a lyrical theme of melting beauty. The development produces a new tranquillo idea in the solo instrument. As part of the dialectic of tranquil and intense, that new theme transforms into something ferocious. After the cadenza the orchestra enters quietly, but works up to a full-throated finish.

What Brahms jokingly called his “wretched adagio” begins with a hymnlike theme, featuring a serene oboe melody that the violin in fact never gets to play (to the perennial annoyance of soloists). Brahms tends to develop his material constantly; the violin enters not with an echo of the oboe theme but a variation of it. In the middle of the simple ABA form the violin dispenses elegant garlands of notes that continue to the end.

All of Brahms’s concertos end in his Hungarian/Gypsy mode, and this one is the most uproarious of the lot. The tensions of the first movement resolve into gaiety. It is laid out more or less in sonata-rondo form, the rollicking leading theme returning regularly. The B-section recalls one of the furioso themes in the first movement, but without the anger. The finale is largely about delight, all the way to a breathtaking coda.”

Brahms included room for a cadenza at the end of the first movement, and the most commonly heard cadenza is by Joachim himself. However, many others have tried their hand at composing a cadenza here, including Leopold Auer, Fritz Kreisler, Jascha Heifetz, Max Reger, George Enescu, Nigel Kennedy, Augustin Hadelich, Joshua Bell, and Rachel Barton Pine among others.

The concerto is known to be one of the most demanding in the repertoire for the soloist, requiring deft finger work, playing arpeggios which are unusual for the violin, some very quick fingering passages, and the use of several double stop harmonic passages. In a manner somewhat consistent with Brahms’ two piano concertos, there is almost a symphonic quality to the concerto, with the interplay between the violin and the orchestra taking on particular importance. It is not merely a violin showpiece, and at times the violin doesn’t carry the main melody. It is in this sense that we find Brahms to be so innovative in creating something with a larger vision than had been traditional, while still using a traditional structure.

Recommended Recordings

For Brahms’ Violin Concerto I don’t have an essential recording, there are simply too many good ones and none that are head and shoulders above the rest. Violinists such as Joseph Szigeti, Jascha Heifetz, Itzhak Perlman, Yehudi Menuhin, and David Oistrakh recorded the concerto multiple times and so sorting through any differences between their individual recordings can be challenging. There have been many times I’ve been able to literally listen to all the commercially available recordings before making my recommended list, but this is not one of those times. So the list below is a “selected” list of my favorites. If your favorite recording of the concerto doesn’t appear, send me a quick message.

As always, the list of recommended recordings below is in chronological order by recording date.

The earliest recording I recommend is from the Russian American superstar violinist Jascha Heifetz and fellow superstar conductor Arturo Toscanini with the New York Philharmonic in a live recording from Carnegie Hall 1935 on the Archipel label. First, the sound is rather awful, and the live audience applauds at the end of each movement, so that may be a dealbreaker for some folks. But the performance itself is electric and has a great deal of verve, especially with Toscanini pushing the envelope as he often did with Brahms. Heifetz too seems more inspired by the live occasion, playing with unusual (for him) depth and expression. The Adagio is heavenly with breathtaking playing. Some of Heifetz’s later recordings are more well known, especially his 1955 recording on RCA/Sony Living Stereo with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. If you need your Heifetz in the best sounding recording, go for that one. But I would recommend sampling all of his recordings of this concerto while you’re at it, with Koussevitzky in Boston from 1939 (on Biddulph), and with George Szell in New York from 1951 (Archipel or Music & Arts). But I still prefer this one with Toscanini.

In somewhat better sound is the 1936 recording from Fritz Kreisler and John Barbirolli with the London Philharmonic Orchestra (Warner and Naxos). The oboe at the beginning of the Adagio is one of the most beguiling I have heard, and Kreisler has a charming, aristocratic tone. While the thicker orchestral parts get lost sometimes, the sound is fuller and warmer than with Toscanini/Heifetz, with the solo part heard to good effect. Kreisler shows tremendous control, even if his sound is not as full as his earlier effort with Blech, the faster passages are dispatched with more accuracy and nobility. The sound is certainly more than adequate for its time, and Kreisler was one of the all-time greats of the violin.

Jumping ahead to 1945, Eugene Ormandy and his fabulous Philadelphia Orchestra are joined by Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti on the Sony label for one of the finest early recordings of this concerto. Ormandy was also a violinist, and he and Szigeti both have the distinction of training under Jenő Hubay, a disciple of Joachim himself. Szigeti recorded this concerto three times commercially, and this recording finds Ormandy and his orchestra tighter and more incisive (and in better sound) than his 1928 recording with Harty. Furthermore, after about 1950 or so, Szigeti’s technique declined and his vibrato became disconcertingly large at times. But here in 1945 what we hear is Szigeti emotionally involved and generating a golden tone. At his best, Szigeti was every bit as impressive as Heifetz or Menuhin back in the day, and this recording highlights the unity of vision between Szigeti and Ormandy. The sound doesn’t have the depth you might hear in a modern recording, but taken on its own terms, this is an outstanding performance.

Another legendary historic recording is from the brilliant French violinist Ginette Neveu joined by the Philharmonia Orchestra and conductor Walter Susskind on EMI/Warner from 1946. Neveu was one of the greatest violinists of her generation before she was tragically killed in an Air France plane crash in 1949 off the Azores. Of course, the sound is what you would expect from 1946, which is to say not great. But also, not too bad. Neveu’s violin solo is warmhearted, assured, and romantically inclined, while Susskind’s accompaniment is fine enough but also lets Neveu be the star. And she is. The Adagio is achingly beautiful, with one of the finest oboe openings on record, followed by Neveu’s soaring tone. The Allegro giocoso finale is not spotless, but Neveu in particular builds excitement. The album is paired with a wonderful rendition of the Sibelius concerto.

It may go without saying that legendary German conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler was one of the finest Brahms interpreters of the century, and his 1949 recording of the concerto with American British violinist Yehudi Menuhin and the Lucerne Festival Orchestra (on the Naxos label) is hands down one of the best. Indeed, for me this is one of Menuhin’s best recordings, capturing him at his artistic peak, and with Furtwängler bringing his own particular stamp to the music. We also begin to hear the piece played at a slower tempo than had been traditional up to that point, with Menuhin giving the notes space to breathe and of course Furtwängler always did that anyway. Menuhin plays the Kreisler cadenza, and his “old-fashioned” vibrato adds color and feeling to the score. Menuhin was known to use a good deal of portamento and often he would “slide” into phrases, but this works to good effect here and lends the reading a nobility. The orchestra has a weighty, full sound and the emotional pulse and exchange between orchestra and soloist is palpable.

The 1953 recording with the Polish British Canadian violinist Ida Haendel with the London Symphony Orchestra and Romanian Sergiu Celibidache on HMV originally (now Testament, but I found it on YouTube) is a celebrated account, and for good reason. First, forget about late Celibidache where he became totally eccentric with his tempos, this early recording finds him well within the mainstream tempos for the era. Ida Haendel was one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, though not always given the same opportunities as male violinists. This recording shows just how awesome her playing chops were, as she was equally adept at technical virtuosity and expressivity. There is richness in her tone, not in the Oistrakh mold, but rather more like Milstein. For 1953, the LSO sounds pretty good despite the mono sound. Suffice it to say Haendel brings power to the larger phrases, while maintaining her lyrical sense elsewhere.

The Russian American violinist Nathan Milstein is one of my favorite violinists of the 20th century, and his 1954 recording with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra under William Steinberg on EMI/Warner shows Milstein with a style that is a bit of a throwback to earlier accounts with his somewhat quicker tempos and his incisive attack. He doesn’t have nearly as much vibrato as Heifetz, Kreisler, and Menuhin, but that is all to the good. Milstein’s style is direct and passionate, but he also doesn’t shortchange the more romantic elements. The Pittsburgh orchestra, under their long-time director William Steinberg, play magnificently and this remains one of the best recordings ever made in the Syria Mosque in Pittsburgh. While Milstein is captured very well, in a few spots the orchestra is not ideally balanced. But the sound is still better than adequate for its time, and the performance still stands out for its sheer elan and thrust. Similarly, his live 1957 Lucerne Festival account with Herbert von Karajan and the Swiss Festival Orchestra on the Audite label is extremely effective at drawing dynamic and emotional contrasts. Karajan’s strong direction is an advantage here, as is Milstein’s essentially lean and incisive tone. The sound from the Lucerne Kunsthaus is on a par with the Steinberg account, and the performance has marginally more electricity and spontaneity. Then we have Milstein’s 1960 recording with Anatole Fistoulari and the Philharmonia Orchestra originally on Capitol/EMI/Angel and now also on the Praga and Urania labels. This may be the best of the Milstein lot, with firm and alert accompaniment from Fistoulari and the Philharmonia, and with Milstein in fiery form. Listen to his entrance in the first movement, then how he pulls back at 3’23” into a more lyrical mood. The sound is certainly better than Steinberg or Karajan, and the orchestra sounds simply superb. It all flows so generously and sounds effortless. The first movement cadenza is nothing short of brilliant, the Adagio is beautiful and memorable, and the finale sizzles. Not to take a backseat to the rest of the Milstein versions, we have the 1974 recording with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and Eugen Jochum on Deutsche Grammophon. This recording is no less impressive, with Milstein’s performance being at least on a par with the others here, and the VPO in good sound under Jochum. Mistein’s interpretations on record are remarkably consistent, so you can’t go wrong with any of them, and they are all highly recommended if you want a more traditional reading with a highly perceptive and massively talented soloist. If I had to choose, I would probably opt for the Fistoulari performance, but that is splitting hairs.

Also from 1954 comes another superb account from Hungarian violinist Johanna Martzy joined by the Philharmonia Orchestra under Paul Kletzki on Warner (as well as reissued on other labels such as Testament and Profil). This is a white-hot performance which doesn’t take a backseat to any other recording in terms of the solo performance. Martzy is simply terrific, and this is one of the great historical accounts of this concerto. Yet another pupil of the Hungarian Hubay, Martzy’s playing may be characterized as rich, full, lyrical, and passionate. The pacing and phrasing are handled masterfully by both Kletzki and Martzy, and the recording from Kingsway Hall in London has warmth and depth. I can’t say enough about the meltingly beautiful Adagio followed by an incandescent final movement, with Martzy bringing an astonishing amount of personality. The sound is good for 1954 but naturally doesn’t have the detail we expect from more modern recordings. Still, I would not want to be without this one.

The great Soviet era Russian violinist David Oistrakh recorded the Brahms concerto several times, and four of them make the recommended list. The first is from 1954 with Oistrakh joined by the Grand Symphony Orchestra of All-Union National Radio Service and Central Television Networks (yes, that is the complete name) otherwise known as the Moscow RTV Orchestra conducted by Kirill Kondrashin on the Melodiya label. Oistrakh’s violin is miked very closely, but this ends up being what makes the recording great as the orchestra’s sound has a sharp twang to it which is not entirely pleasant. But Oistrakh’s solo here is memorable and so characteristic of his playing that it deserves a recommendation. Also from 1954 is Oistrakh with the Staatskapelle Dresden under conductor Franz Konwitschny on the Deutsche Grammophon label. While Oistrakh is not miked as closely as in Moscow, that is okay because the entire recording is better balanced and the orchestral contribution here is more desirable. While the sound is a bit thin and distant in spots, there is no doubt this is another masterful account from Oistrakh not only technically, but also in terms of emotional involvement. Next is Oistrakh’s 1960 recording with Otto Klemperer and the Orchestre National de France. Of course, Klemperer was a terrific Brahms conductor, and of the four recordings with Oistrakh recommended here, this one has the best sound (even better than Szell’s later account). This is a sort of halo around the sound which provides a nice resonance. The interplay between Oistrakh and Klemperer is nearly ideal, with Klemperer’s pacing giving Oistrakh’s ample and rich tone room to breathe. This is truly a magisterial recording. Finally, there is Oistrakh’s 1970 account on Warner with George Szell and The Cleveland Orchestra, where not surprisingly Oistrakh is given a much more disciplined and tauter accompaniment from Szell. The sound is better, although not quite as good as I would expect from 1970. Still, Oistrakh’s vision of the work is pretty consistent and while the finale is taken more broadly, we still hear his stunningly beautiful tone and quick vibrato which lengthens out nicely in more lyrical passages. All around you might say Oistrakh was one of the very finest interpreters of this concerto, and all of these accounts deserve to be recognized.

Soviet Russian violinist Leonid Kogan is vastly underrated in my view, and he is also one of my favorite violinists of the 20th century. His 1958 live Brahms concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Pierre Monteux on Doremi or West Hill feels like an event, and the performance has energy and bite. Kogan is fairly closely miked (although I don’t mind), and the orchestra is relatively well balanced. But just be aware the sound is somewhat compromised for 1958 and keep in mind this was a live recording, so don’t expect a sonic spectacular. But what is spectacular is Kogan’s burnished and precise tone partnered with a dramatic sensibility which fully equals Oistrakh or Milstein. There is just something about his silvery and clean tone which I love. Monteux was also a greatly underrated Brahms conductor in my view, and his overall vision pairs nicely with Kogan. Kogan’s 1959 studio account with Kirill Kondrashin and the Philharmonia Orchestra from Abbey Road originally on EMI, now on Archipel and others, is in significantly better sound and still retains most of the positive qualities of the Boston performance. Kondrashin was a frequent partner, and he and Kogan have a good rapport. Kogan’s violin is captured a bit more warmly, even though the sound is pretty dry. But what makes Kogan one of the best is fully present, his silvery tone with a very sweet top range and a wonderful singing quality, but then he could cut through butter with the edge of his sound if needed.

I went back and listened to Belgian violinist Arthur Grumiaux’s 1958 recording of the concerto with Eduard van Beinum and the Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam on Philips/Universal, and it is a beautiful performance which deserves recommended status. Grumiaux, of course, had a lovely tone which he uses to great effect here. In many ways this is a traditional, middle of the road interpretation. But when the playing is so fine, and the sound so good for its time, it ranks highly. Grumiaux was not flashy in the Heifetz, Kreisler, or Szigeti mold, but rather relied on an almost unparalleled lyrical sensibility which came through in a singing tone which is wonderful to hear. Don’t get me wrong, he had the virtuosic chops, but was in tune with the emotional variations that are needed in the score, and he executes. Van Beinum was also not flashy, but his accompaniment is solid and complementary with Grumiaux.

Another notable Doremi reissue from Boston is from 1959, this time with French violinist Christian Ferras and the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Charles Munch. Ferras is another favorite violinist, and here he is caught at his peak. The orchestra sounds much better than on the Monteux recording above, with Munch leading a characteristically extroverted and rhythmically astute reading. Ferras brings a thoughtful and swaggering performance, he being a most sensitive artist. I like the feeling of this live event, with Ferras’ violin captured in close sound which I like. This is an utterly beautiful performance, with a heartbreakingly gorgeous Adagio, and a lilting Hungarian-esque finale which is quite satisfying. Ferras' 1964 recording with Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic on Deutsche Grammophon, captured in the wonderful acoustics of the Jesus-Christus-Kirche in Berlin, is a model of refinement and beauty. It may not have quite the electricity of the Munch account but hearing his sensitive and lovely playing alongside Karajan’s BPO, then at their peak, is a treat. The orchestra sound is somewhat heavier than in Boston, while Ferras’s tone is a bit thinner, but the performance pays dividends in terms of additional details heard in the bass line and in the richness of the acoustic. Ferras was ultimately a tragic figure, committing suicide in 1982 at the age of 49. But his lyrical and evocative playing will live on through his recordings.

The American Jewish violinist Michael Rabin also had a tragic story. A prodigy from a young age, Rabin was struck by a neurological condition which would curtail his career and would eventually contribute to his death at the age of 35 from a fall in his New York City apartment. Rabin had made his Carnegie Hall debut at the age of 13 in 1950, and from there he embarked on a productive career as a soloist for a time before more health setbacks. The recording I recommend here is a live recording from 1967 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Rafael Kubelik from the Ravinia Festival on the Doremi label. Rabin was making something of a comeback at this point, and his musical instincts and virtuosity are not only fully intact, but this is a performance of real stature and personality. His tone was leaner and more direct in the manner of Milstein or Kogan, and this recording will truly give you a glimpse into his genius. We can revel in this performance and appreciate Rabin’s immense talent, as well as the tragedy of his life. Kubelik’s accompaniment with the CSO is very well done. The sound is more than adequate, but keep in mind it is from a live source.

Jumping ahead to 1992, there is the live recording from Tokyo featuring the Russian born British violinist Viktoria Mullova joined by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and Claudio Abbado on Philips/Universal (now on Abbado Deutsche Grammophon boxed set). I have long admired Mullova, and her desire to continue growing as an artist. Her tone has less vibrato than we normally hear, and her dramatic sensibilities are outstanding, and just listen to her top notes…something special. The first movement is taken at a reasonable pace which gives Mullova some flexibility in her phrasing. Abbado and Mullova are effective partners, and of course the BPO plays wonderfully as they usually do (even if the timpani is too far forward in the sound). Mullova projects a lean strength which gains in authority as the work progresses, and her playing of the Joachim cadenza is varied and enjoyable. The recording has a sense of occasion, and though the Suntory Hall acoustics are just a bit cavernous for Mullova’s tone, this is a great sounding live performance. The finale is balanced and has good orchestral power and detail, with Mullova in exciting form.

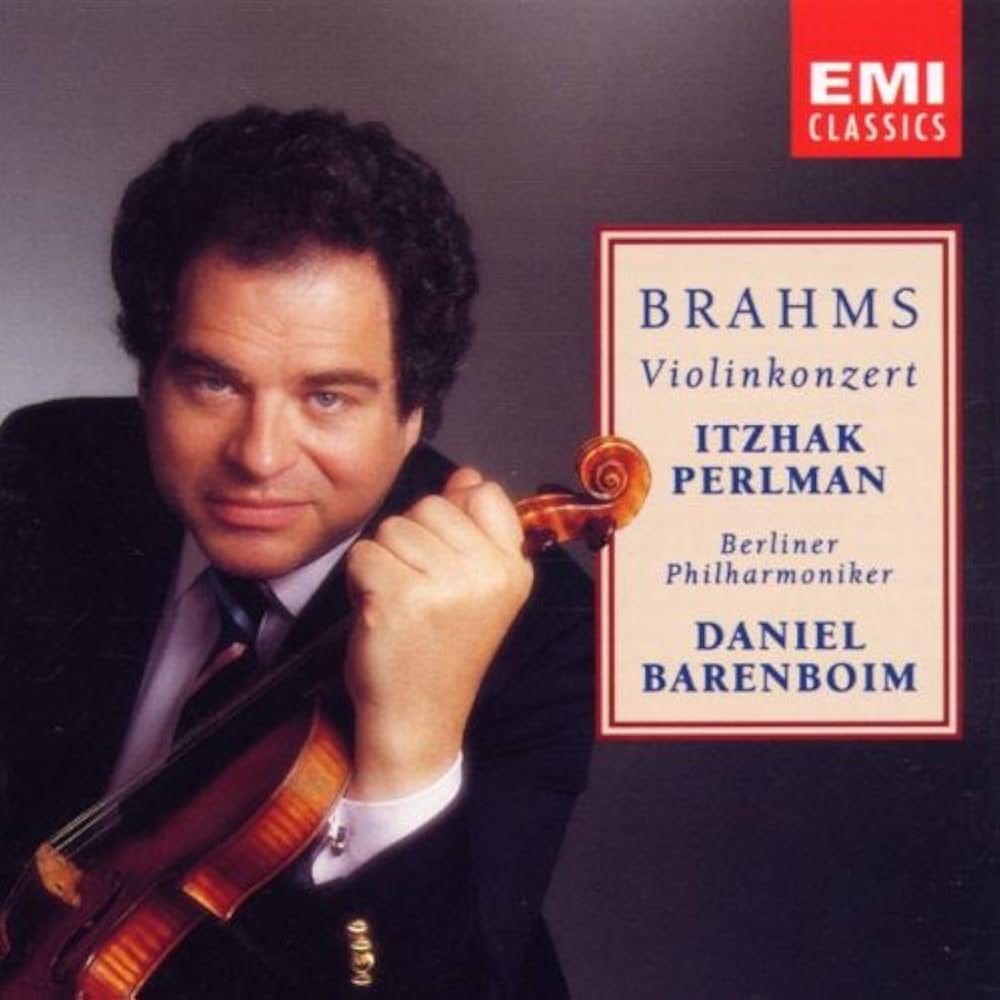

Also recommended recording from 1992 is the live recording with soloist the legendary Itzhak Perlman joined by Daniel Barenboim conducting the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra on EMI/Warner. Perlman’s full and flowing tone is ideal for the Brahms concerto, and I prefer the sound of this recording to Perlman’s 1977 recording with Giulini also on EMI/Warner. Perlman’s violin is miked somewhat artificially close, but his playing is nothing short of gorgeous. Barenboim sounds more engaged than Giulini and the entire performance is about five minutes quicker than with Giulini. The BPO plays marvelously and the sound from the Schauspielhaus (now called the Konzerthaus) in Berlin is excellent. Barenboim and Perlman are both traditionalists, so what you will hear is nothing revolutionary, but the portamento and emotive style from both is rather delightful.

Moving ahead to 2001 is the stunning recording from the then 21-year-old American violinist Hilary Hahn with the Academy of St. Martin’s-in-the-Field under Sir Neville Marriner on the Sony label. While the ASMF doesn’t have quite the heft of some larger orchestras, the real highlight is the amazing playing of Hahn. Hahn’s star hasn’t burned out yet either, she is still playing and recording at an extremely high level today. But the assurance she has on this recording is extraordinary, and she impresses not only technically but also musically. Her intelligence around dynamics and building tension and knowing when to back off in a more lyrical mood is something to hear. Marriner and the ASMF are a bit too relaxed for my taste, but many will like their approach. But back to Hahn…her ability to step on the accelerator and create magic just never gets old for me, and behind even her most tender playing is a feeling that fire will erupt at any moment. I love that, and I really love the way she uses portamento in the finale. She reminds me of Martzy and Kogan and fully deserves a spot near the top. The sound from the studio recording is very good.

The 2002 recording from American violinist Rachel Barton Pine with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under conductor Carlos Kalmar on the Cedille label is among the finest modern recordings of this concerto. Barton Pine plays with confidence and power here, and some listeners have even labeled this recording to be essential. Barton Pine has not garnered the attention she deserves in my estimation, and this recording is a prime example of her artistry. The overall conception from Barton Pine and Kalmar is more traditional in pacing, with the entire concerto actually being taken quite slowly in overall timing, but to me it never feels that way. Barton Pine’s warm and full sound is reminiscent of Perlman, but she finds even more nuance, variation, and shading. This is a performance to get lost in, to revel in, to let the time get away from you. Soloist and orchestra are well-nigh perfectly balanced, and there is drama and personality aplenty. The Adagio is breathtaking, and the finale I didn’t want to end. Barton Pine includes her own cadenza on a separate track, as well as the Joachim cadenza. The Brahms concerto is paired with the very substantial Joachim concerto on this album, and this is probably the finest recording of that concerto you will find anywhere.

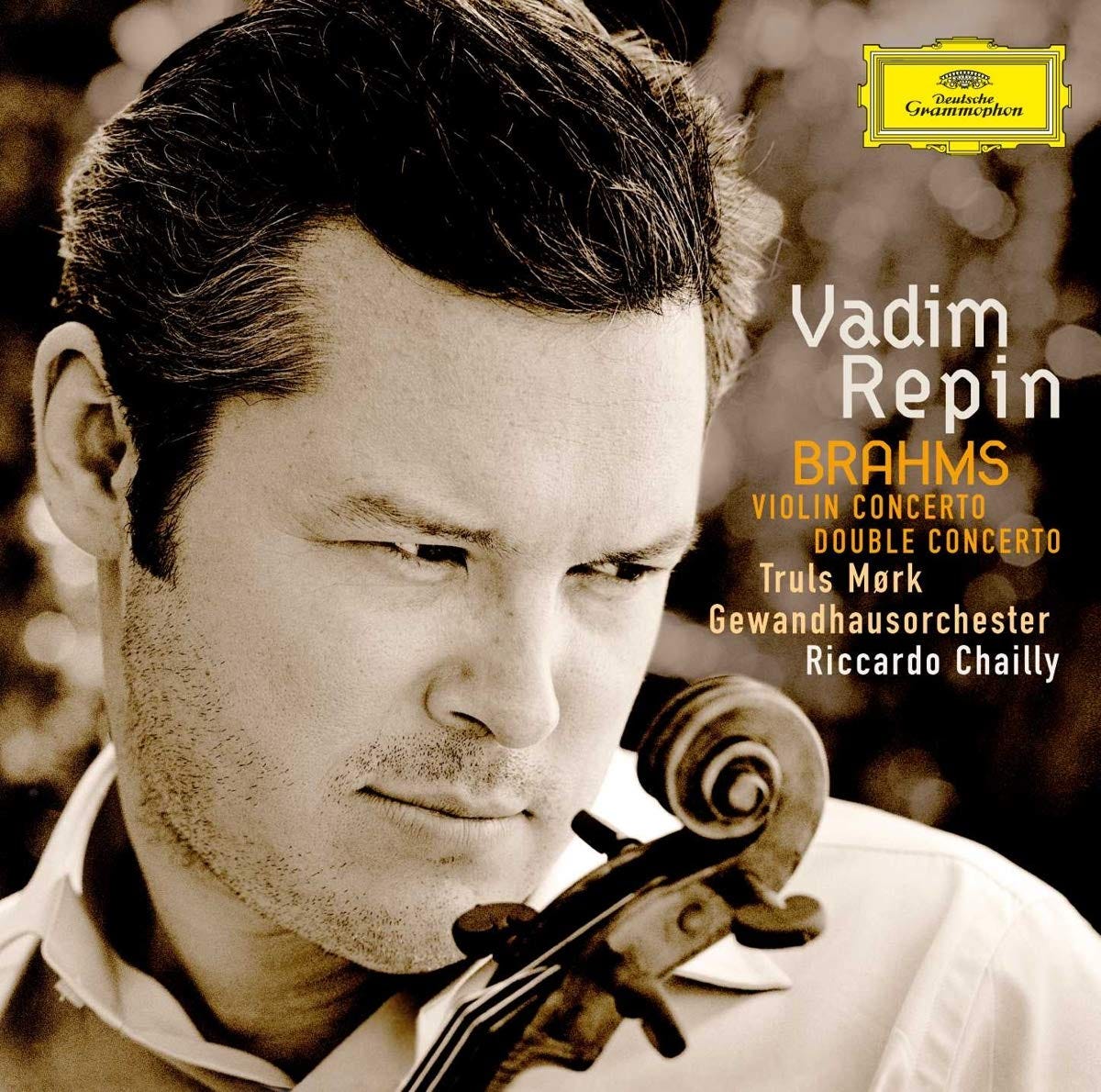

The immensely gifted Russian Belgian violinist Vadim Repin recorded the Brahms concerto in 2008 with the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig under Riccardo Chailly for Deutsche Grammophon, and it is a stunning recording. Repin has long been one of the foremost virtuosos in classical music, and his technique and sound are exemplary. But moreover here he plays with supreme musicality, and Repin brings a flowing and lyrical sense to much of the first movement without resorting to any fireworks. He uses the Heifetz cadenza in this recording, but he is so convincing in everything he plays. The double stops are produced with seemingly little effort, and he can withdraw or bolster his tone on the spot at will. The Leipzigers under Chailly sound terrific, balanced with good depth of sound, and there is a good amount of detail heard in a well engineered recording. The Adagio is sublime in its innocence and inevitability, while the finale has a perfect amount of lift and playfulness, the brass and woodwinds along with bass strings are caught superbly. A triumph of a recording.

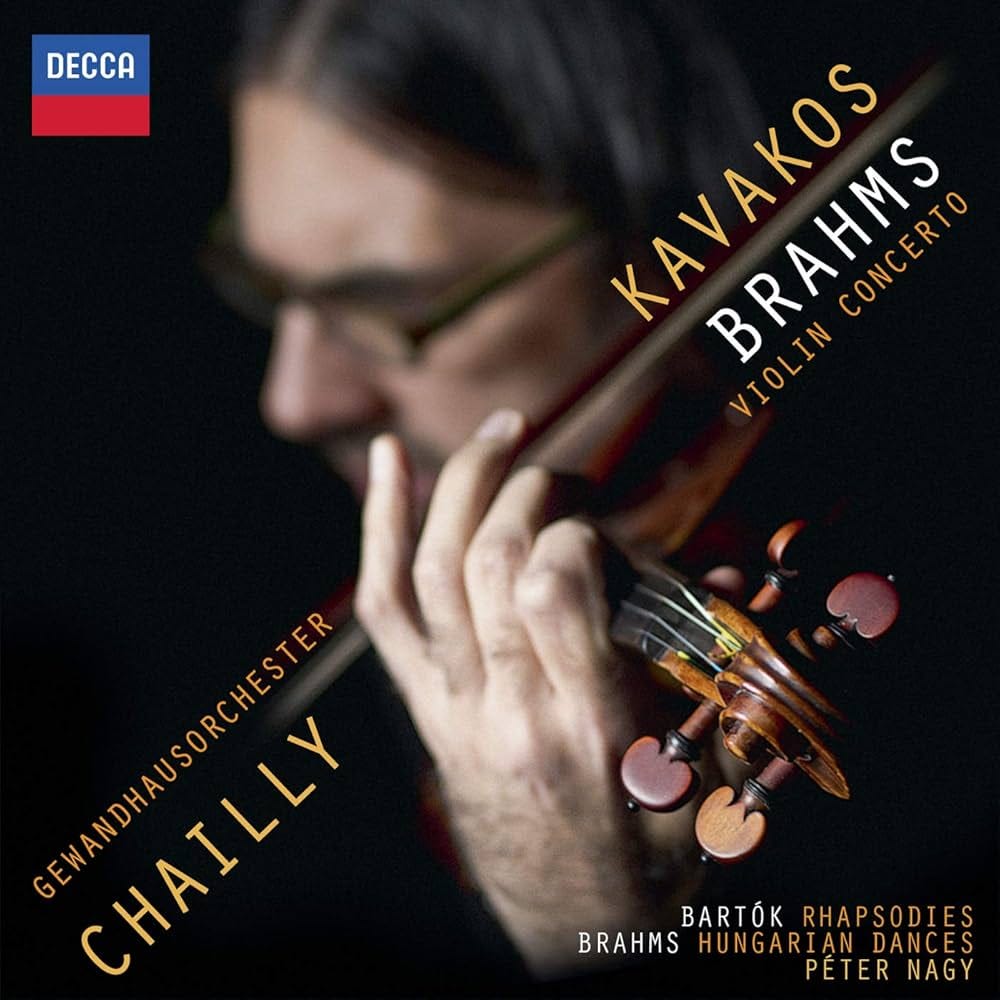

The next recommended recording on the list is the outstanding 2013 account on Decca by Greek violinist Leonidas Kavakos and the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig under Riccardo Chailly. I don’t think brilliant is too strong of a word for Kavakos’ playing on this recording, balancing virtuosity and expressiveness quite well together. Chailly and the Leipzigers’ roughly contemporary recordings of the Brahms’ complete symphonies is instructive with how they will perform here, which is to say superbly. Still, this is no historically informed performance with relaxed tempos in the first two movements especially. Kavakos is a bit of a throwback to Milstein or Menuhin, and I mean that as a compliment. His tone is firm and assured, with plenty of depth and flexibility in dynamics and phrasing. Kavakos also brings some tender intimacy to the Adagio, not to mention the second theme in the opening movement. The double stops are to die for honestly, and Chailly and his team partner ideally to create a luscious sound world which is very satisfying. Kavakos’ varies his vibrato from hardly any to pretty wide in spots, and this feels purposeful and effective. The sound is exemplary, even better than with the Repin recording from the same source.

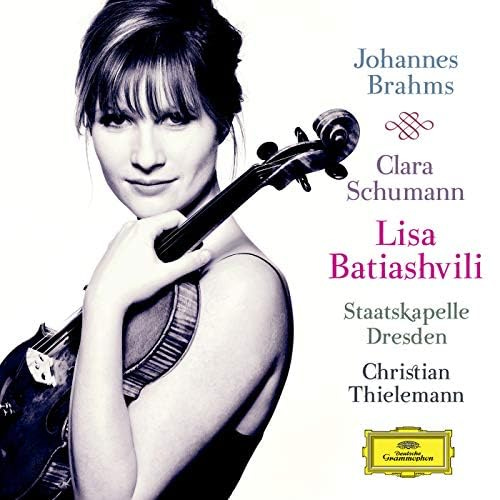

Georgian violinist Lisa Batiashvili has long been one of my favorite modern day violinists, and her Brahms concerto from 2013 with the Staatskapelle Dresden under Christian Thielemann on Deutsche Grammophon is simply terrific. For once Thielemann doesn’t conduct like the walking dead, and Batiashvili enters with authority and brio in the opening movement. I remember when I first heard this recording shortly after it was released and thinking the acoustic of the Lukaskirche in Dresden gave the recording an atmospheric and almost otherworldly feeling, and that still strikes me now when I listen. Batiashvili’s pitch and tone seem perfect to my ears, though I might have preferred her violin to be slightly closer in the picture. But she plays gorgeously in the lyrical second theme of the first movement, and clearly revels in the more romantic mood. As the movement progresses her playing intensifies and she brings quite a fire to the second half of the movement. The Adagio is beautifully played, but not overemoted as Batiashvili avoids oversentimentalizing the main subject. The finale is blazing, one of the quickest on the recommended list, with Batiashvili pulling out subtle touches here and there which add to the reverie. The playing of the Dresden orchestra is good, though to mind not at the level of the Leipzigers with both Repin and Kavakos. Thielemann is a sympathetic accompanist, but he tends to draw with broad strokes rather than in stark detail and to be honest I miss some of Chailly’s detail. The overall sound is good, though as I mentioned a bit overreverberant.

I have enjoyed pretty much every recording Israeli violinist Vadim Gluzman has made, and his Brahms concerto is no exception. He is joined on the 2015 recording by the Lucerne Symphony Orchestra conducted by American conductor James Gaffigan on the BIS label. The quality of the recorded sound is a great asset, there is a wonderful transparency to the sound and while the Lucerne band is not a powerhouse, they play splendidly. Gluzman enters with swagger and a wiry tone, but also with passion. There is an almost irresistible sense of emotion from his violin, and his playing most reminds me of Oistrakh. His playing has a sweetness of tone that is disarming, and like Repin he is able to control dynamics and nuance at a moment’s notice. Occasionally I would like more heft and drama from Gaffigan and the orchestra, but the basic vision is of an intimate, more transparent, almost chamber like performance, and to that end they are quite successful. Overall timing is pretty standard, and Gaffigan gives Gluzman plenty of room to breathe. The cadenza of the first movement is well done, and the Adagio is poignant and sentimental. Orchestral details never heard before come through thrillingly, and the BIS engineering from the Kultur und Kongresszentrum in Lucerne is top shelf. Gluzman even adds some appealing portamento in the Adagio. The finale is exciting and urgent, with Gluzman and the orchestra complementing each other perfectly. This is one of the most enjoyable of modern recordings.

The 2019 recording by the brilliant German American violinist Augustin Hadelich with the Norwegian Radio Orchestra under Miguel Harth-Bedoya on the Warner label ranks with the best as well. Speeds are on the more traditional side, but the sound from the Norwegians is extremely appealing, immediate and fresh. Hadelich’s entrance is similarly sparkling, followed by some of sweetly lyrical moments that are worth the price of admission. Importantly Hadelich adds his own impressive cadenza in the first movement, something that not all listeners will like, but for me it is well integrated. The slow movement is played with pathos, the opening oboe setting the tone for a well judged solo part from Hadelich. It has a natural flow with nice detail from the orchestra noted, and with Hadelich reaching inward for some truly beautiful playing. The finale bounces along with a perfect lilt, the balance between orchestra and soloist ideally captured. They sound as though they are having fun too, the dance-like quality coming through well. The recording quality is outstanding in my opinion. The Ligeti concerto which follows the Brahms is as unique and interesting a pairing as you are likely to hear.

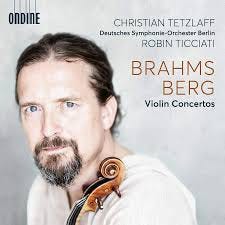

If you want an even fresher approach with marginally quicker tempos and perhaps less schmaltz than the older, traditional style I recommend Christian Teztlaff’s 2022 recording with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin conducted by Robin Ticciati on the Ondine label. Recorded in the Philharmonie in Berlin, the recording has plenty of amplitude and resonance to it, with the playing of the DSO Berlin matching Tetzlaff’s essentially ripe and energetic vision. There is not a lot of wallowing in phrases here, but what Teztlaff does he does extremely well and he is followed precisely by Ticciati and his orchestra. You can tell that Teztlaff is more invested in this performance than his prior outing with Dausgaard from 2007, there is more emotion present in his tone and more effective subtle nuances. This performance puts to rest my prior belief that the concerto must ooze romanticism and heaviness to really work. To the contrary, this more direct and stirring rendition is every bit as moving. The Adagio has plenty of touching moments, but the underlying pulse keeps moving underneath Teztlaff’s silvery tone. The finale takes off pretty fast, and maintains a zippy tempo throughout. The excitement at the end is palpable. The sound from Ondine is excellent.

Honorable Mention Recordings

There are so many good recordings of this concerto, you may find some real gems among those listed below. While I haven’t included them in my recommendations, these are still very considerable interpretations which deserve to be heard (if you have time!).

A quick note about Heifetz’s 1955 recording with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on RCA/Sony Living Stereo. Yes, it is a great sounding album, and yes it is a legendary recording. For me, it is taken too fast to really appreciate Brahms’ scoring and to me it feels as though Heifetz shortchanges the emotion and lyricism in favor of virtuosic fireworks. Others will likely disagree, but I just can’t give it a top recommendation.

Szigeti / Hallé Orchestra / Harty (M & A 1928)

Heifetz / Boston Symphony Orchestra / Koussevitzky (Sony 1939)

Schneiderhan / Staatskapelle Dresden / Böhm (Warner 1940)

Busch / New York Philharmonic / Steinberg (M & A 1943)

Huberman / New York Philharmonic / Rodzinski (M & A 1944)

Schneiderhan / Berlin Philharmonic / Van Kempen (DG 1953)

Ferras / Vienna Philharmonic / Schuricht (Archipel 1954)

Heifetz / Chicago Symphony Orchestra / Reiner (Sony 1955)

Francescatti / Philadelphia Orchestra / Ormandy (Sony 1956)

Morini / Royal Philharmonic Orchestra / Arthur Rodzinski (DG 1956)

Menuhin / Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Kempe (Warner 1957)

Francescatti / Vienna Philharmonic / Mitropoulos (Orfeo 1958)

Szeryng / London Symphony Orchestra / Monteux (Sony 1958)

Stern / Philadelphia Orchestra / Ormandy (Sony 1960)

Spivakovsky / New York Philharmonic / Krips (Doremi 1961)

Francescatti / New York Philharmonic / Bernstein (Sony 1962)

Grumiaux / Philharmonia Orchestra / C. Davis (Universal 1972)

Szeryng / Concertgebouw Amsterdam / Haitink (Universal 1974)

Perlman / Chicago Symphony Orchestra / Giulini (Warner 1977)

Stern / New York Philharmonic / Mehta (Sony 1978)

Accardo / Leipzig / Masur (Universal 1979)

Mutter / Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Karajan (DG 1981)

Kremer / Vienna Philharmonic / Bernstein (DG 1982)

Ughi / Philharmonia Orchestra / Sawallisch (RCA 1982)

Little / Royal Liverpool / Handley (Warner 1991)

Kremer / Concertgebouw Amsterdam / Harnoncourt (Warner 1997)

Vengerov / Chicago Symphony Orchestra / Barenboim (Warner 1999)

Shaham / Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Abbado (DG 2000)

Rachlin / Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra / Jansons (Warner 2004)

Fischer / Netherlands / Kreizberg (Pentatone 2006)

Kashimoto / Staatskapelle Dresden / Chung (Sony 2007)

Skride / Stockholm / Oramo (Orfeo 2009)

Faust / Mahler Chamber / Harding (HM 2011)

Capucon / Vienna Philharmonic / Harding (Warner 2012)

Jansen / Santa Cecilia / Pappano (Decca 2015)

Shaham / The Knights / Jacobsen (Canary 2019)

Dego / BBC / Stasevska (Chandos 2023)

Whew! That was a mouthful and then some. I do realize this is a long post, and I hope it has been a worthwhile read for you. For me, it has been a bit of a labor of love. Working my way through so many recordings has been a challenge, but it has also been a lot of fun for me. I hope you are able to find some recordings you enjoy of this great concerto.

Join me next time when we will cover #85 on the list, Gabriel Fauré’s Requiem. See you then!

_____________

Notes:

Fink, Michael Dr. THE STORY BEHIND: Brahms' Violin Concerto. https://www.riphil.org/blog/the-story-behind-brahms-violin-concerto. January 13, 2022.

Fuller-Maitland, J.A. Joseph Joachim, London and New York, J. Lane, 1905, p. 55.

Gal, Hans (1963). Johannes Brahms. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 217.

Steinberg, Michael. "Bruch: Concerto No. 1 in G Minor for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 26". San Francisco Symphony. Archived from the original.

Swafford, Jan. Violin Concerto in D, Opus 77. Boston Symphony Orchestra program notes found online at https://www.bso.org/works/brahms-violin-concerto.

Swafford, Jan. Johannes Brahms: a biography 1997:448ff discusses the writing of the Violin Concerto.on 7 November 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

https://www.azquotes.com/quote/1463358

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Violin_Concerto_(Brahms)?scrlybrkr=40ad99ec

![Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-Flat Major, Op. 83 & Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 77 (Remastered 2023) [Live] - Album by Arturo Toscanini, Vladimir Horowitz & Jascha Heifetz - Apple Music Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-Flat Major, Op. 83 & Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 77 (Remastered 2023) [Live] - Album by Arturo Toscanini, Vladimir Horowitz & Jascha Heifetz - Apple Music](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!1XSN!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fab66afcb-011c-4c49-a8f4-ecd0018b7f1f_221x229.jpeg)

![Brahms, Joseph Szigeti With The Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy – Violin Concerto – Vinyl (LP, Reissue, Mono), [r16938420] | Discogs Brahms, Joseph Szigeti With The Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy – Violin Concerto – Vinyl (LP, Reissue, Mono), [r16938420] | Discogs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Bn33!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F18ff6fb7-4b76-4e64-b7d9-4854b685c783_599x590.jpeg)

![Brahms, Ida Haendel And The London Symphony Orchestra Conducted By Sergiu Celibidache – Brahms Violin Concerto – Vinyl (LP), 1955 [r15584119] | Discogs Brahms, Ida Haendel And The London Symphony Orchestra Conducted By Sergiu Celibidache – Brahms Violin Concerto – Vinyl (LP), 1955 [r15584119] | Discogs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!DmEl!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdc6beba2-7aa1-402f-a087-592340432fd9_599x590.jpeg)

![Brahms - Milstein, The Philharmonia Orchestra, Anatole Fistoulari – Violin Concerto – Vinyl (LP, Stereo), 1961 [r14989885] | Discogs Brahms - Milstein, The Philharmonia Orchestra, Anatole Fistoulari – Violin Concerto – Vinyl (LP, Stereo), 1961 [r14989885] | Discogs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!zvH9!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc72a7502-ea70-4c04-9d4c-1170f45a3e9b_600x591.jpeg)

![Brahms · Tchaikovsky / David Oistrakh, Staatskapelle Dresden, Franz Konwitschny – Violin Concertos · Violinkonzerte – CD (Compilation, Mono), 1988 [r11455969] | Discogs Brahms · Tchaikovsky / David Oistrakh, Staatskapelle Dresden, Franz Konwitschny – Violin Concertos · Violinkonzerte – CD (Compilation, Mono), 1988 [r11455969] | Discogs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Cq4z!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0ee2b783-f492-4b78-82e4-cb3eea79670a_300x298.jpeg)

![Brahms, Vadim Gluzman, Luzerner Sinfonieorchester, James Gaffigan, Angela Yoffe – Violin Concerto & Sonata No. 1 – SACD (Hybrid, Multichannel), 2017 [r10493947] | Discogs Brahms, Vadim Gluzman, Luzerner Sinfonieorchester, James Gaffigan, Angela Yoffe – Violin Concerto & Sonata No. 1 – SACD (Hybrid, Multichannel), 2017 [r10493947] | Discogs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!8Oa8!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa45c60b4-33dd-4402-b3e0-8a7a6648d375_225x225.jpeg)

I just listened to both Pine and Hahn. While both are wonderful, I prefer Pine. The dynamics are much better and her ability to be gentle and yet commanding is amazing. Her musicality is second to none

Para mí, las mejores grabaciones son Klemperer/Oistrakh y Reiner/Heifetz.