Building a Collection #81B

The Pines of Rome (I Pini di Roma)

By Ottorino Respighi

____________

Welcome back! The second of the three “Roman Trilogy” tone poems from Italian composer Ottorino Respighi is The Pines of Rome (1924). The Pines of Rome is arguably the most famous and most often performed and recorded of the trilogy.

Ottorino Respighi

The biographical information below on Respighi is repeated from #81A (Fountains of Rome), so if you have already read the following, feel free to jump down to the information on the Pines of Rome.

The Italian composer Ottorino Respighi was born in Bologna, Italy in 1879 and died in Rome in 1936. Encouraged to pursue his interest in music from a young age, Respighi would eventually become one of the leading composers of the early 20th century. Respighi’s works span operas, ballets, orchestral suites, songs, chamber music, concertos, and transcriptions of 16th to 18th century Italian music. However, it was his three kaleidoscopic orchestral suites that form the “Roman Trilogy” (The Fountains of Rome, The Pines of Rome, and Roman Festivals) which brought him international fame and that continue to live on in frequent recordings and performances.

After taking lessons in violin and piano as a youth, Respighi enrolled at the Liceo Musicale di Bologna where he continued his music studies. For a few seasons he was the principal violinist at the Russian Imperial Theatre in Saint Petersburg, and it was during that time he met the Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. He took some lessons from Rimsky-Korsakov, and Respighi’s compositions would eventually show some definite influence from the great Russian. Giuseppe Martucci, Respighi’s composition professor in Bologna, would later say of him, "Respighi is not a pupil, Respighi is a master."

Respighi relocated to Rome in 1913, where he would remain for most of the rest of his life between short periods in Bologna. In Rome he would take the position of professor of composition at the Liceo Musicale di Santa Cecilia. While continuing to teach a bit, from 1923 onward Respighi focused most of his time on composition. Once he began to develop an international reputation, Respighi toured other countries, often guest conducting his own works in the United States, South America, and Europe. While working on his opera Lucrezia in 1935, Respighi became ill with bacterial endocarditis. He died four months later at the age of 56. His wife Elsa would survive him by some 60 years, tirelessly championing her husband’s music for the rest of her life.

Respighi’s great gift was putting into music the visual images and emotions evoked by cherished places. In particular, his orchestration is often colorful and exquisite in detail, but also contains a lot of charm and beauty. In terms of music history Respighi falls somewhere between the Romantic and the Avant-Garde or modern time periods, but is often considered to be “neoclassical”, meaning his compositions are highly tonal, accessible, and relatively easy to understand. He wrote a great deal of programmatic music, or music that is meant to depict ideas or images that are non-musical in nature. In other words, there is a background narrative driving the music. Italian music was undergoing a revival after World War I especially, and Respighi began studying Italian Medieval and Renaissance music. He either transcribed works (which is where a composer rewrites a piece of music, either solo or ensemble, for another instrument or other instruments than which it was originally intended) or borrowed some themes or snippets from ancient works. He did this most famously in another popular work, Ancient Airs and Dances for orchestra.

There is much evidence, including Respighi’s own comments, to suggest that his goal was to become a great opera composer. No doubt he would have been greatly influenced by the operas of Italian compatriots Giuseppe Verdi and Giacomo Puccini. But even though Respighi would compose several operas, none of them took hold with audiences and critics. Indeed, even his other compositions attracted little attention until he composed The Fountains of Rome, finished in 1916. Respighi worked a few times with the famous Russian ballet impresario Sergei Diaghelev, most notably creating the ballet La boutique fantasque, after Rossini in 1918. Several other Respighi compositions went on later to become well-known, including Gli uccelli (The Birds), Trittico botticelliano (Three Botticelli Pictures), Impressione brasiliane (Brazilian Impressions), and Il tramonto (The Sunset).

The Pines of Rome (1924)

Following the success of the Fountains of Rome, Respighi turned to The Pines of Rome in 1924, depicting “the century-old trees that so characteristically dominate the Roman landscape and become testimony for the principal events in Roman life.”

The movements are described below by Donald Ferguson in his 1968 book Masterworks of the Orchestral Repertoire: A Guide for Listeners:

I. I Pini di Villa Borghese

This movement portrays children playing by the pine trees in the Villa Borghese gardens, dancing the Italian equivalent of the nursery rhyme “Ring a Ring o’ Roses” and “mimicking marching soldiers and battles; twittering and shrieking like swallows.” The Villa Borghese, a villa located within the grounds, is a monument to the Borghese family, who dominated the city in the early seventeenth century. Respighi’s wife Elsa recalled a moment in late 1920, when Respighi asked her to sing the melodies of songs that she sang while playing in the gardens as a child as he transcribed them, and found he had incorporated the tunes in the first movement.

II. Pini presso una Catacomba

In the second movement, the children suddenly disappear and shadows of pine trees that overhang the entrance of a Roman catacomb dominate. It is a majestic dirge, conjuring up the picture of a solitary chapel in the deserted Campagna; open land, with a few pine trees silhouetted against the sky. A hymn is heard (specifically the Kyrie ad libitum 1, Clemens Rector; and the Sanctus from Mass IX, Cum jubilo), the sound rising and sinking again into some sort of catacomb, the cavern in which the dead are immured. An offstage trumpet plays the Sanctus hymn. Lower orchestral instruments, plus the organ pedal, suggest the subterranean nature of the catacombs, while the trombones and horns represent priests chanting.

III. I Pini del Gianicolo

The end of the third movement features this recording of the song of a nightingale which Respighi incorporated into the score. The third is a nocturne set on the Janiculum hill and a full moon shining on the pines that grow on it. Respighi called for the clarinet solo at the beginning to be played “come in sogno” (“As if in a dream”). The movement is known for the sound of a nightingale that Respighi requested to be played on a phonograph during its ending, which was considered innovative for its time and the first such instance in music. In the original score, Respighi calls for a specific gramophone record to be played–”Il canto dell’Usignolo” (“Song of a Nightingale, No. 2”) from disc No. R. 6105, the Italian pressing of the disc released across Europe by the Gramophone Record label between 1911 and 1913. The original pressing was released in Germany in 1910, and was recorded by Karl Reich and Franz Hampe. It is the first ever commercial recording of a live bird. Respighi also called for the disc to be played on a Brunswick Panatrope record player. There are incorrect claims that Respighi recorded the nightingale himself, or that the nightingale was recorded in the yard of the McKim Building of the American Academy in Rome, also situated on Janiculum hill.

IV. I Pini della Via Appia

Respighi recalls the past glories of the Roman empire in a representation of dawn on the great military road leading into Rome. The final movement portrays pine trees along the Appian Way (Latin and Italian: Via Appia) in the misty dawn, as a triumphant legion advances along the road in the brilliance of the newly-rising sun. Respighi wanted the ground to tremble under the footsteps of his army and he instructs the organ to play bottom B♭ on the 8′, 16′ and 32′ organ pedals. The score calls for six buccine – ancient circular trumpets that are usually represented by modern flugelhorns, and which are sometimes partially played offstage. Trumpets peal and the consular army rises in triumph to the Capitoline Hill. One day prior to the final rehearsal, Respighi revealed to Elsa that the crescendo of “I Pini della Via Appia” made him feel “‘an I-don’t-know-what’ in the pit of his stomach,” and the first time that a work he had imagined turned out how he wanted it.

Even though audiences initially booed some parts of The Pines of Rome at the premiere, the triumphant march down the Appian Way that concludes the work won the audience over and was greeted with a tremendous ovation. The work was soon played all over Europe to great acclaim, and became a frequent concert piece in the United States as well. Several Hollywood film composers in particular have pointed to Respighi’s Pines as being inspirational for their work. There were critics that condemned the work for being trashy, overblown, or even too conservative. But time has proven the work’s staying power, as well as its advocacy from conductors such as Toscanini, Reiner, Koussevitzky, Stokowski, and others.

Recommended Recordings

Until recently, I had Sir Antonio Pappano’s recording at the top of the heap for all three of the Roman Trilogy tone poems, but my assessment has changed. The Pappano is very good, and still recommended. For now I don’t have an essential recording of The Fountains of Rome, but I recommend several recordings below, and many more in the honorable mention category.

I lived at the North American College on the Janiculum Hill in Rome at two different times between 1991 and 1995, and Respighi’s music has personal meaning for me. I have been fortunate to travel to many places in the world, but nowhere has the sentimental hold over me that Rome has. The way the light hits the buildings in the morning and evening, the sounds and smells of the vibrant cultural center of the city, the ghosts lingering around all the ancient monuments, the markets and the food, and the way the city’s history and reputation overshadow the present day all make it an awe-inspiring place to be. What we have with Respighi’s music, for me, is the apogee in the development of the symphonic poem, which spins a narrative based on a place. Respighi perfectly captures the moods, images, and feelings of Rome in a way that almost defies words. This music is close to my heart.

Legendary Italian maestro Arturo Toscanini had a special relationship with Respighi’s music, and was an early advocate for these tone poems. His 1953 recording with the NBC Symphony Orchestra on RCA (Sony) set a standard for decades to come with these performances, even with the somewhat compromised and boxy sound. Toscanini’s reading is full-blooded and headstrong, emphasizing dramatic and dynamic contrasts better than almost anyone else. While the off-stage trumpet is a little too far offstage and difficult to hear in Pines Near a Catacomb, the bird sounds in The Pines of the Janiculum are very well done for a recording this old. I will mention again that many critics have noted that the Pristine label version is a significant improvement in sound, though I haven’t heard it myself.

Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra recorded The Pines of Rome for RCA Living Stereo in 1959 and many count this as THE essential recording of the work. I agree it is a terrific recording, and certainly one of the best ever made of Pines. First, the sound from RCA is excellent for any period of time, but to think this was recorded over 65 years ago is unbelievable. The sound picture is full spectrum with a wide dynamic range and an incredible level of detail. Moreover, Reiner conjures some amazingly ripe and intelligent playing from the CSO. Textures are rich and layered, Reiner finding just the right mood for each movement. The Pines of the Appian Way is particularly impressive and overwhelming in its power and impact. Tempos and balances are well nigh perfect, and the tam tam splashes are quite effective and atmospheric.

The 1960 Antal Dorati recording of Pines with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra for Mercury Living Presence remains as vivid today as when it was released. Typical of the Living Presence series, we have to live with some dryness in the sound, but there is no lack of depth. Just listen to the bass and pedal on the Appian Way combined with the brass…it is overwhelming in its intensity. The trumpets are simply heroic. The opening Villa Borghese is sparkling and vibrant. The Janiculum is tastefully done, tender and lyrical without tipping over into schmaltz. Indeed, Dorati keeps things moving well, though he does slow things down on the march in the final movement. Dorati seems to have the measure of Pines in a way that somewhat eludes him in Fountains, and while the sound is not as sumptuous as for Reiner, and even though the Minneapolis Symphony band was not quite the Chicago Symphony, this is still an excellent recording.

One of the finest albums Lorin Maazel ever recorded, in my opinion, was his 1976 pairing of The Pines of Rome and Roman Festivals with The Cleveland Orchestra for Decca. The recording features ripe and lush Decca analog sound, and details come to the fore wonderfully. Maazel’s direction here captures the fun and colorful aspects of the score, complete with terrific contributions from brass, percussion, and strings. Catacombs is subtle, but contains plenty of atmosphere, even if the “offstage” trumpet sounds quite immediate. The bass line comes through marvelously throughout, but especially in the Appian Way, where the crescendo is big enough to put us in the middle of the action. The organ pedal hits you in the gut too. Kudos to legendary Kenneth Wilkinson for the superb engineering.

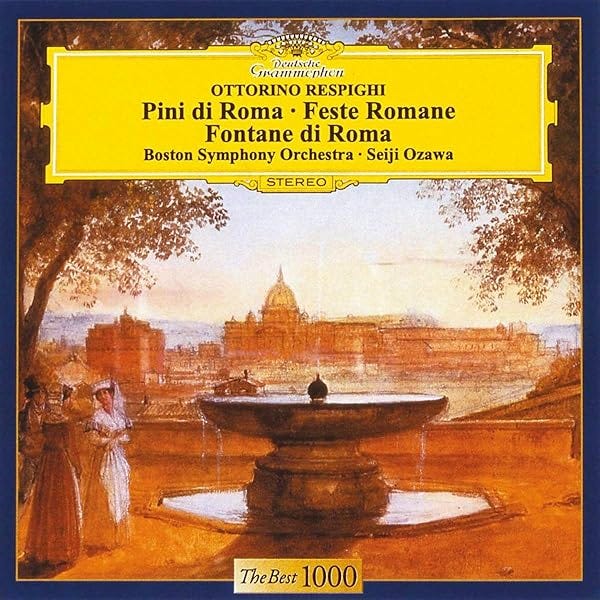

The Pines from 1979 with Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony Orchestra on Deutsche Grammophon is also recommended. The whole trilogy is good from Ozawa and the BSO, but Pines (and Festivals) are particularly good. I love the sound and feel of Symphony Hall in Boston on this recording, there is plenty of atmosphere and air around the sound, creating a nicely resonant, almost cathedral-like effect. The BSO percussion and brass shine in the Villa Borghese, while Ozawa draws evocative and touching playing in Catacombs (listen to the harp, just beautiful). The slightly off stage trumpet is done to absolute perfection here, creating an almost impressionistic sound world along with the strings. The strings and brass hit the climax hard, but not too hard, which is ideal for this movement. The Janiculum is equally effective, the opening piano and clarinet delicately and subtly delivered. Later the BSO strings are beguiling. The Appian Way has an excellent rhythmic pulse, with clear bass and plenty of power.

The relationship between Decca and Charles Dutoit and the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal was extremely productive, and they made many excellent recordings together in the 1980s. Their recording of Pines from 1983 is the most noteworthy selection from their Respighi album, and of course it boasts the rich and full sound typical of their releases from the time period. Dutoit also has an urgency missing from many other recordings, and it gives the reading a pleasing freshness and spark. The march down the Appian Way is performed with electricity, energy, and abandon and the terrific sound quality adds to the effect. However, Dutoit’s overall vision is not one of power, but rather refinement. Thus, if you are looking for a more visceral impact, turn to Muti or Maazel.

Speaking of Riccardo Muti, there is no doubting that his 1985 traversal through the triptych is one of the finest available, and the Pines is very well done. The sound from EMI (now Warner) still has some glare in louder passages and this is not the most subtle reading on record. But Muti lets The Philadelphia Orchestra off the leash which presents the Pines as a colorful and high octane adventure. The entire album is passionate and Italianate in character, and the Philadelphians are spectacular. The Catacombs and Appian Way are as exciting as they come, and the level of engagement from Muti and the orchestra are consistently high throughout. The audio engineering remains an issue at both the high and low end, even after remastering, although it is somewhat better than the original master.

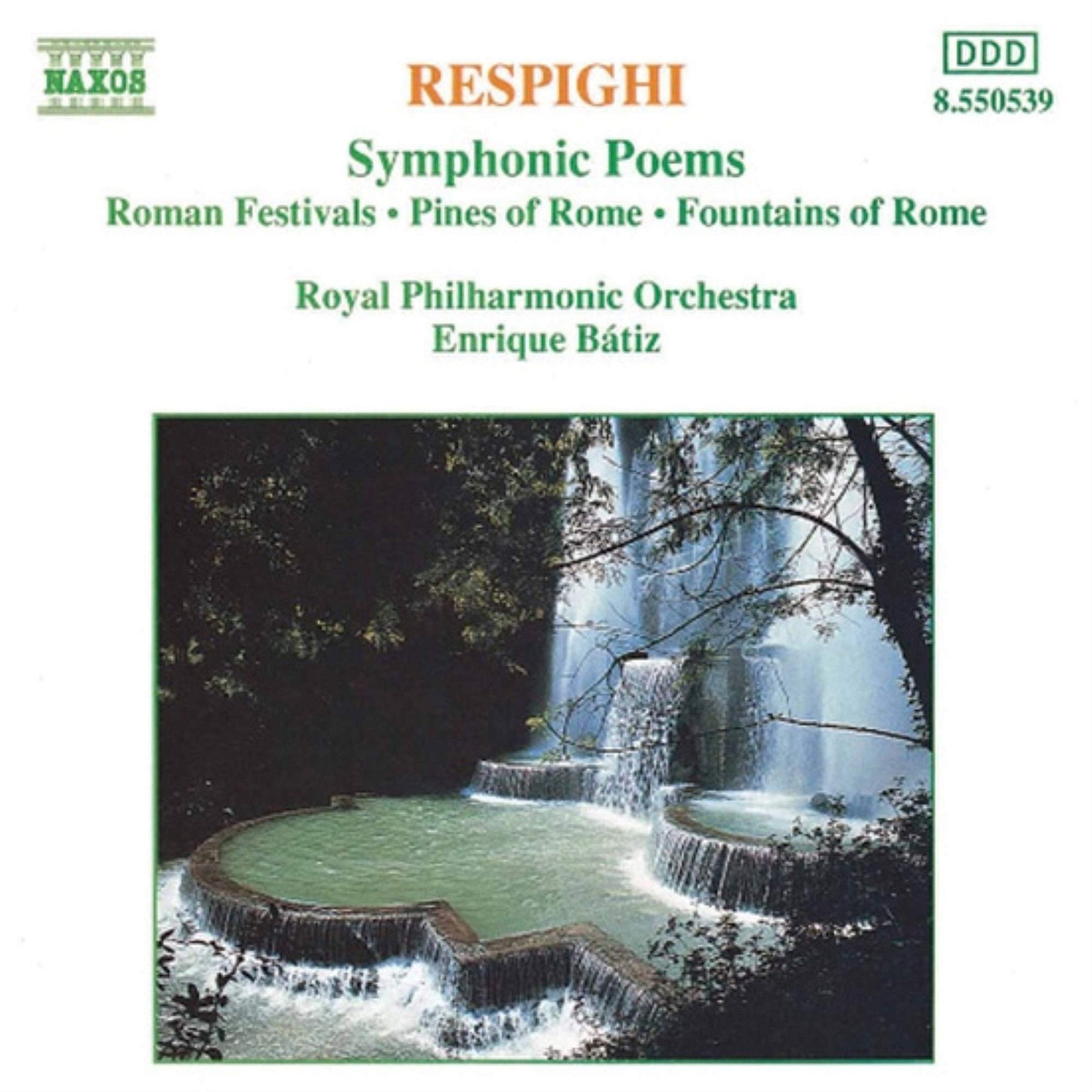

In 1991 the Naxos budget classical label was still quite new, but one of the finest recordings the label has produced in my opinion is their recording of Respighi’s Roman Trilogy under Mexican conductor Enrique Bátiz made in 1991 with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. This performance of The Pines of Rome takes a backseat to no one in either interpretation or sound. Bátiz’s reading reminds me of Muti’s, big boned and heavy on spectacle. But that is the point, isn’t it? Brass, woodwinds, and strings are incisive and there is an impressive range of precision from the RPO. There is no dawdling either, as Bátiz keeps things moving with great momentum without making it feel rushed. I also enjoyed the first half of Catacombs and the Janiculum more than many other recordings, the mood is evocative and vivid.

The 1991 Chandos recording from the Philharmonia Orchestra under Yan Pascal Tortelier remains recommended for its natural flair, consistency, and superb sound. There is plenty of power as well as tonal color on display here, and while the Villa Borghese is a bit too calculated, the imposing Catacombs and roaring Appian Way more than compensate. The Janiculum captures the sense of the outdoors quite well, and also the solitude you might experience on a walk on the hill above the city. The playing of the Philharmonia is outstanding in its refinement and detail.

From the opening notes of the Pines of Villa Borghese, it’s clear that Antonio Pappano’s recording with the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia on EMI (Warner) will be something special. This is played with zing, and on the quicker side, but certainly effectively. Prominent reviewer David Hurwitz calls Pappano’s Catacombs “dead”, but I could not disagree more. The offstage trumpet is handled perfectly, the buildup to the climax is clear and impactful with the trumpets and horns coming through terrifically. The Pines of the Gianicolo is delicately played as it should be, with plenty of imagination and wonderful playing from the woodwinds followed by the strings. The Appian Way builds slowly but surely, Pappano measuring the distance of the Roman soldiers perfectly in proportion to the pace and dynamics of the music. The gradual buildup is managed splendidly, with volume and mass growing, but with Pappano also holding some in reserve for closer to the end in what turns out to be an epic conclusion. The acoustical space is perhaps too cavernous to be ideal for this music, but it is perfectly acceptable.

Similar to their Fountains, Robert Treviño and the Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI (Turin) on the Ondine label bring a freshness of approach and sound to Pines as well. The first thing I notice is the stunningly immaculate and clean sound, in fact almost too clean. But the amount of detail is amazing. It gets off to a good start with a vivid Villa Borghese, while the first half of Catacombs is appropriately evocative. I wasn’t sure what to make of the bigger second half of Catacombs in the steady buildup up to the climax, where Treviño smooths out the strings, making it feel less weighty. Upon listening to it again, I quite like the effect and when considering the theme it feels appropriate. The Janiculum is extremely effective, subtle and tender. The Appian Way reminds me more of Dutoit and is less overwhelming than Muti or Pappano, but no less effective. I like what Treviño does with the score, and so this is another excellent version of Pines.

Honorable Mention Recordings

Symphony of the Air / Leopold Stokowski (Urania 1958)

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Lorin Maazel (DG 1958)

London Symphony Orchestra / István Kertész (Decca 1968)

New Philharmonia Orchestra / Charles Munch (Decca 1969)

New York Philharmonic / Leonard Bernstein (Sony 1970)

The Philadelphia Orchestra / Eugene Ormandy (Sony 1971)

Atlanta Symphony Orchestra / Louis Lane (Telarc 1983)

San Francisco Symphony Orchestra / Edo de Waart (Universal 1983)

New York Philharmonic / Giuseppe Sinopoli (DG 1991)

Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields / Sir Neville Marriner (Universal 1991)

London Symphony Orchestra / Lamberto Gardelli (Warner 1995)

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra / Lorin Maazel (Sony 1996)

Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra / Jesús López Cobos (Telarc 1999)

São Paulo State Symphony Orchestra / John Neschling (BIS 2008)

Dallas Symphony / Eduardo Mata (Sono Luminus 2011)

Sinfonia of London / John Wilson (Chandos 2019)

Thank you for joining me again for this installment of Building a Collection. Next time we will conclude Respighi’s Roman Trilogy with Roman Festivals. See you then!

____________

Notes:

Blain, Terry (29 June 2012). "Composers - Respighi, Ottorino: The Roman Visionary". BBC Music Magazine. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

Brennan, Gerald. Gailey, Meredith. Lewis, Uncle Dave. Minderovic, Zoran. Rodman, Michael. Schrott, Allen. Woodstra, Chris. All Music Guide to Classical Music, The Definitive Guide. All Media Guide. Pp. 1089-1090. Backbeat Books, San Francisco. 2005.

Duchen, Jessica (February 2012). "Balancing Act". Opera News: 18–22.

Ferguson, Donald N. (1968). Masterworks of the Orchestral Repertoire: A Guide for Listeners. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-816-65762-9.

Heald, David (2006). Respighi - Preludio, Corale e Fuga, Burlesca, Rossiniana, Five Etudes-Tableaux (PDF) (Media notes). Gianandrea Noseda, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. Chandos Records. CHAN 10388. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

Hurwitz, David. Respighi: Roman Trilogy/Pappano. Review online at https://www.classicstoday.com/review/review-14254/.

Ottorino Respighi: A Dream of Italy 1982, 15:36–15:50.

Perry, Tim. RESPIGHI Roman Trilogy Review. http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2007/nov07/respighi_trilogy_3944292.htm

"(Program notes)" (PDF). University of Washington Symphony Orchestra. 2007. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

"The Three Arts". The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland). 28 December 1920. p. 12 – via newspapers.com.

Webb, Michael (2019). Ottorino Respighi: His Life and Times. Troubador Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-789-01895-0.

https://santacecilia.it/en/orchestra-and-chorus/orchestra/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transcription_(music)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottorino_Respighi

![Respighi, Riccardo Muti, The Philadelphia Orchestra – The Pines Of Rome / The Fountains Of Rome / Roman Festivals – Vinyl (DMM (Direct Metal Mastering), LP, Stereo), 1985 [r4725858] | Discogs Respighi, Riccardo Muti, The Philadelphia Orchestra – The Pines Of Rome / The Fountains Of Rome / Roman Festivals – Vinyl (DMM (Direct Metal Mastering), LP, Stereo), 1985 [r4725858] | Discogs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ewx-!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2a0d1dbe-df6e-4ce1-b709-521af67156b9_599x594.jpeg)

For completists there is another great (hard to find) italian version that deserves a mention: a young Daniele Gatti conducting the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. CD Conifer out to print.