Building a Collection #77

Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104

By Antonín Dvořák

____________

“I like praying there at the window when I look out on the green and at the sky. I study with the birds, flowers, God and myself.”

– Antonín Dvořák

Welcome back regular readers, and if this is your first time checking out my publication, I am happy you are here! At #77 on our list we encounter the great Czech composer Antonín Dvořák for the second time (his Symphony no. 9 “From the New World” came in earlier at #15. Dvořák’s Cello Concerto is without a doubt one of my favorite concertos ever written, it is an absolute gem, and some consider it the greatest concerto ever written for cello.

Antonín Dvořák

Antonín Dvořák (d(ə-)VOR-zha(h)k;) was born in Muhlhausen, Germany (Nelahozeves, Bohemia) in 1841 and died in 1904 in Prague, Czech Republic. Even though his hometown was technically ruled by Germany at the time, the people considered themselves to be Czech. Dvořák was definitely Czech through and through, and proud of his heritage.

Antonin was the eldest of nine children, and the son of a butcher. He was expected to follow his father into the butcher business, but as it happens that was not Antonin’s fate. His first love was always music, and at the age of 16 he asked his father’s permission to pursue a musical career. His father agreed, but with the condition that Antonin study the organ with the practical thought it would provide a living for the young man. Antonín Dvořák graduated from the Organ School in Prague, but was barely scraping by playing piano in local establishments. Eventually he landed a job as a violinist at the Provisional Theater, which presented mostly plays and operas in the native Czech language.

In a way, Dvořák came along in the right place at the right time. Being proud of his heritage led to a desire on his part to bring a true Czech idiom to his love of music. At the time, the Germans dominated the music scene across Europe. It is true the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana had made his mark, and Dvořák was an admirer of Smetana. Similar to Smetana, Dvořák wanted to bring a more nationalistic flavor to his music. While his early attempts at opera were not successful, Dvořák began to have more success when he began composing other works.

Dvořák married a former piano student of his, Anna Cermakova, and their family began to grow. Tragedy soon befell them, as they lost three young children to various causes within the span of less than two years. The losses were devastating for Dvořák, a devout Catholic. He poured his grief into his composing, and the result was his Stabat Mater from 1877. It became the first real Czech sacred masterpiece, as well as Dvořák’s first major triumph as a composer. He and his wife would go on to have six more children, and would have a happy family life.

From that point on, it seems Dvořák’s creativity exploded with compositions that garnered widespread acclaim. His Symphonic Variations (1877) and the popular Slavonic Dances (1878) soon followed, and then his Serenade in D minor (1878). Other major works would come later, the most well-known being the Violin Concerto (1879), Symphony no. 7 (1885), Symphony no. 8 (1889), Symphony no. 9 “From the New World” (1893), String Quartet no. 12 “American” (1893), and his last concerto composition the Cello Concerto (1895).

Dvořák began a correspondence with the composer Johannes Brahms in 1878, and a friendship developed that was to enrich the lives of both men. Dvořák is often associated with Brahms, as Brahms himself greatly admired Dvořák’s work. Dvořák’s music often paid tribute to Brahms in terms of mood and structure, and both men had a tremendous gift for melody and orchestration. During the time their careers overlapped, Brahms and Dvořák were considered the two best composers in the world.

In 1891, received the unbelievable offer of $15,000 to come to New York City and become the director of the National Conservatory of Music. After a long time deciding, Dvořák finally agreed and they packed up the family and embarked on the long sea voyage to the United States. Upon settling in Manhattan, Dvořák began his time teaching and composing. They enjoyed New York, but the pace of city life was perhaps not the best match for a family that spent most of their evenings at home. Although the family considered going home for summers, another invitation came to Dvořák from Spillville, Iowa of all places. Spillville was a small, almost entirely Czech-speaking village in Iowa. Dvořák was quite comfortable there, and the family felt at home. In hindsight, one might conclude that Dvořák came away from his time in America with an overly positive view of the country, although he may not have been exposed to some of the less bucolic elements.

Besides being very impressed with America in general, Dvořák was also profoundly impacted by his exposure to American folk music during his stay in the United States, and in particular African-American spirituals and Native American music. Although his claims that American folk music was similar to European folk music were not entirely substantiated, his claim that black spirituals and native music could become the basis for all sorts of musical genres was actually born out in the work of composers such as Gershwin, Joplin, Price, and others. Through his teaching and visits to rural America, Dvořák heard a lot of folk music and became fascinated with African-American melodies and themes. He even incorporated some similar sounding melodies into his New World symphony and American quartet. Dvořák attempted to depict some of the idealism and energy of America at the time, while at the same time remaining true to his own style and voice.

After a few years Dvořák and his family returned home. With his reputation solidified, and now financially secure, Dvořák’s last few years were more taken up with teaching and representing the interests of Czech music. Dvořák’s works are some of the most easily enjoyed and accessible pieces in all of classical music. You might say his music is memorable, melodic, as well as colorful and vigorous. Dvořák is one of the leading “nationalist” composers by virtue of his use of folk tunes and popular melodies from Bohemia, and by taking those elements and integrating them into the classical genre. Today his music is part of the standard repertoire for orchestras all over the world.

Cello Concerto in B minor

Dvořák was still in America when he wrote his final concerto, this one for cello. Despite his aversion to using the cello as the subject for a concerto, he went on to write this masterpiece which became arguably the greatest cello concerto ever written and some would say one of the greatest concertos written for any instrument. There is a story of Dvořák visiting Niagara Falls during his stay in the USA, and upon seeing it declared, “My word, that’s going to be a symphony in B minor.” Although a symphony in B minor never materialized, his soon to be composed cello concerto is indeed in B minor, perhaps owing to that visit to Niagara.

During Dvořák’s time as Director at the National Conservatory in New York, he heard a cello concerto (perhaps no coincidence also in B minor) composed by his teaching colleague composer Victor Herbert. He was so impressed, he was inspired to write his own cello concerto. As it turns out, cellist Hanus Wihan had been asking Dvořák to write him a concerto for years. Dvořák finally had the impetus to do it, and thus began work on the concerto. Between visits home to the Czech Republic and his time in New York, Dvořák began composing and then continued to revise the sketches over the course of about six months, and it was completed in February 1895. Although Wihan was the official dedicatee of the concerto, and it was planned that he would be the first to perform it publicly, circumstances dictated that Wihan was not available for the premiere. In November 1895, the London Philharmonic Society wrote to Dvořák to ask him to conduct a concert in London. Dvořák immediately thought of premiering his cello concerto with Wihan as soloist, but the date chosen had already been set and Wihan had previous obligations. To complicate matters, Wihan had proposed to Dvořák several fairly major edits and changes to the concerto, which Dvořák adamantly rejected. At the concert, the concerto was played by soloist Leo Stern. Wihan remained the work’s dedicatee, and later performed it to great acclaim.

Dvořák wrote to his publishers: “I give you my work only if you will promise me that no one – not even my friend Wihan – shall make any alteration in it without my knowledge and permission, also that there be no cadenza such as Wihan has made in the last movement; and that its form shall be as I have felt it and thought it out.”

The finale, he wrote, should close gradually with a diminuendo "like a breath ... then there is a crescendo, and the last measures are taken up by the orchestra, ending stormily. That was my idea, and from it I cannot recede.”

The concerto is in a pretty standard concerto structure of:

Allegro (B minor then B major)

Adagio, ma non troppo (G major)

Finale: Allegro moderato — Andante — Allegro vivo (B minor then B major)

The work’s duration is about 40 minutes.

Upon reading the final score, his colleague and friend Brahms is reported to have said, “Why on earth didn’t I know that one could write a cello concerto like this? Had I known, I would have written one myself long ago!”

The solo part for cello is certainly demanding, but it is not designed to be a showpiece. Rather the cello is integrated, and the orchestral part is more developed and more important than in some other concertos.

Allen Schrott in the All Music Guide describes the concerto movements:

“The first movement is constructed around two main themes, the first of which is surprisingly brief, and the second of which (stated by solo horn), was one of the composer’s personal favorites. The passing of these ideas back and forth between the soloist and orchestra allows for substantial thematic development; the first, brief theme is given substantially more weight in the eventual recapitulation.

In contrast to the dynamic first movement, the second movement Adagio opens with a more peaceful theme in G major. A middle section in G minor incorporates the melody from Dvořáks own song, “Leave me alone” - a favorite tune of his sister-in-law, Josefina Kaunitzova, who had taken ill during the concerto’s composition. Dvořák was devoted to her, and her death not long after his return home would cause him to revise the end of the work to include the same song in a lengthy epilogue. The finale (Allegro moderato) is an energetic rondo, followed by an epilogue which recalls the opening movement, as well as the song mentioned above.”

The Essential Recording

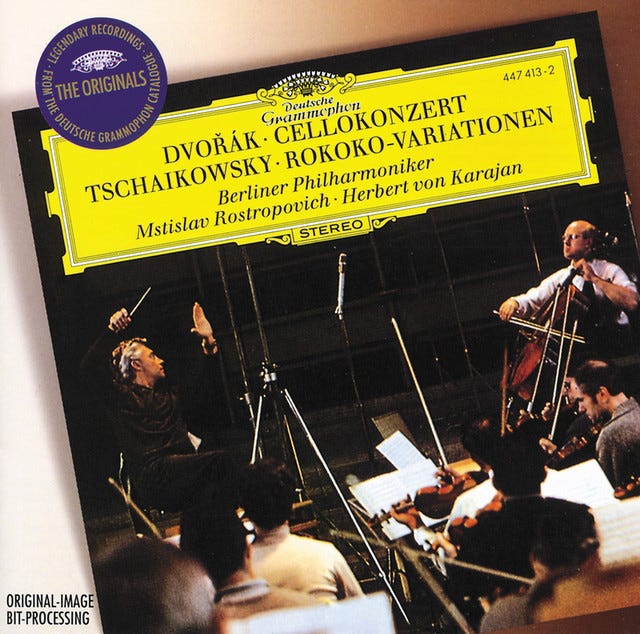

Mtislav Rostropovich was one of the supreme soloists of all-time, and for many the greatest cellist ever. Sometimes forgotten is that Rostropovich also began conducting later in his career to some acclaim, directing strongly emotional performances. But on this essential account of the Dvořák Cello Concerto he is joined by Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra recorded by Deutsche Grammophon in 1968 in Berlin’s Jesus Christ Kirche.

What we can hear on this recording is the rich tone produced by Rostropovich, as well as the ease with which he plays even the most difficult passages. The confidence and power in his playing, along with his mastery of the most subtle details, are heard well in this recording. The range displayed by Rostropovich, along with the emotional intensity of his playing, make this a special recording. But that is not all, as he is accompanied by Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic caught at the height of their artistic time together. For me, this is one of the best recordings Karajan ever made, and that is saying a lot since he and the Berliners recorded a massive discography. The orchestral playing here is epic and dramatic, giving the piece the weight and gravitas it fully deserves. The sound is very good analog for the time period, at times the loudest passages lose some clarity, but the recording venue provides depth and warmth to the sound. A few times I find myself wishing the cello was slightly closer (for that you can listen to Rostropovich’s recording with Boult, see below), but overall it is a realistic sound picture.

This is a grand vision of the work, spacious and sweeping, and the performance is captivating. This is a true partnership, with the size of Rostropovich’s personality matched well by that of Karajan and the Berliners. They are equally eloquent in the loudest passages as well as the more lyrical. Karajan’s “larger than life” is somewhat indulgent, and some listeners may prefer more direct. But I still find it irresistible.

Gramophone Magazine said of this recording:

“There have been a number of outstanding recordings of the Dvorák Concerto since this DG record was made, but none to match it for the warmth of lyrical feeling, the sheer strength of personality of the cello playing and the distinction of the partnership between Karajan and Rostropovich. Any moments of romantic license from the latter, who's obviously deeply in love with the music, are set against Karajan's overall grip on the proceedings. The orchestral playing is superb…Rostropovich's many moments of poetic introspection never for a moment interfere with the sense of a spontaneous forward flow. The description 'legendary' isn't too strong for a disc of this calibre.”

Recommended Recordings

There are so many recommended recordings, and as we often see, there are a plethora of honorable mention recordings as well. Some listeners will find those every bit as good as the recommended ones.

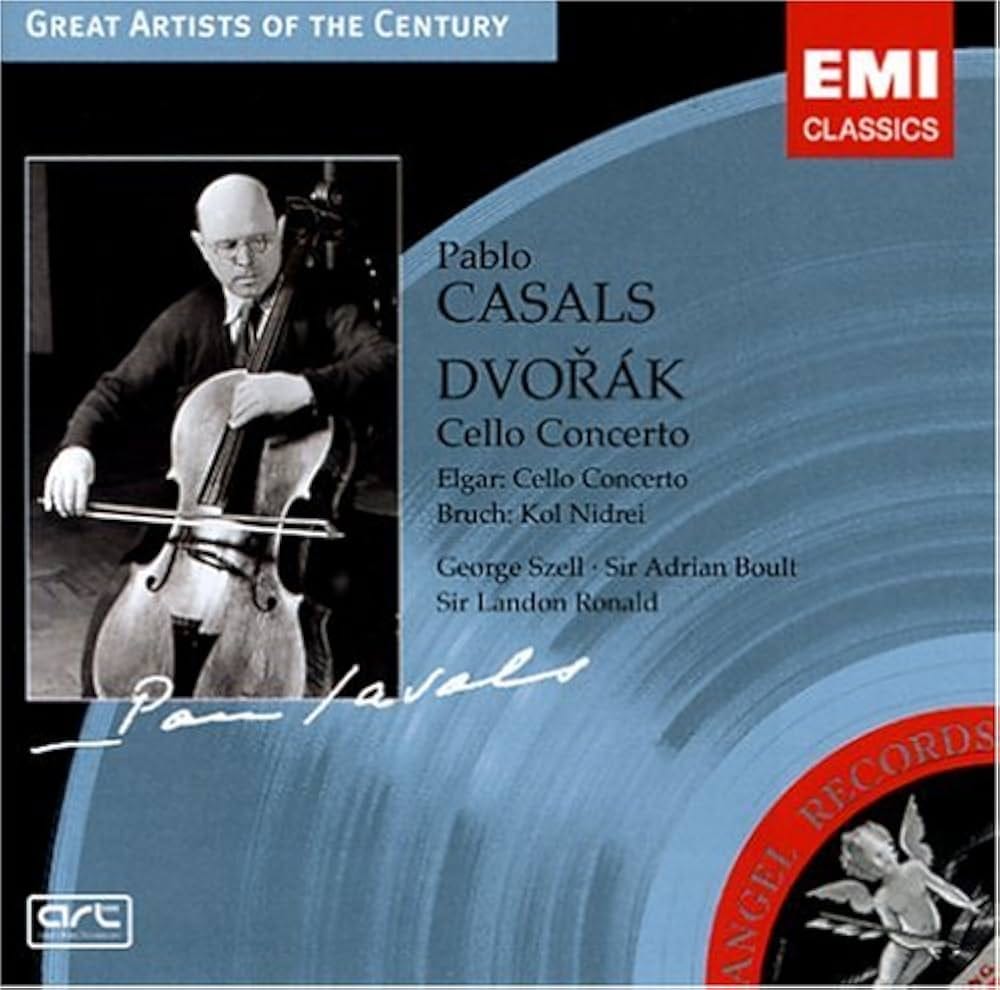

Pablo Casals’ 1937 recording with a young George Szell leading the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra on EMI/Warner, Naxos, and other labels, is a sort of landmark early recording. The sound is not good by any means, but decent for 1937 and has improved with remasters over the years. Casals was not by any means the first great cellist to meet the Dvořák concerto, but as timing would have it, he took great advantage of the blossoming recording medium to put some wonderful performances on record. This is one of them. Casals also possessed a large and generous tone, which mirrored his personality, and he exudes warmth and romanticism on this recording. You won’t hear the sort of orchestra-soloist balance heard on more modern recordings, here it is Casals out front conspicuously in the sound picture. Whether that was a by-product of the recording technology, or purposeful on his part, doesn’t really matter these days. Szell for his part was a terrific Dvořák conductor, and of course you have the Czech Philharmonic sounding excellent. Szell had not started pushing things forward incessantly as he would in Cleveland, but he does keep Casals from schmalzing it up too much. In summary, a treasured recording.

The second Rostropovich recording I am recommending is his 1957 Abbey Road recording with Sir Adrian Boult and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra on EMI/Warner (though I prefer the Praga version I heard). The sound is considerably better than with Talich (in honorable mention), and Rostropovich plays with intensity and power. The cello is spotlit, but the orchestra is fairly close too. Boult’s accompaniment is solid if rather faceless. The faster passages in the Finale by Rostropovich are stunning, and he enters phrases with a real purpose. Boult and Rostropovich avoid getting too bogged down and drawing phrases out for effect. I like the directness of this account, and it has a bounce and a joy that is missing from some other recordings. The Adagio is managed well by Rostropovich, though perhaps less sensitively by Boult. Listen from 11’10” in the Finale to the end to sample the subtlety of Rostropovich and then the terrific buildup to the conclusion.

I hope you will indulge me a bit to include a sentimental favorite of mine, but it is also in my view one of the very best early stereo recordings of the concerto. The 1958 recording by cellist Gregor Piatigorsky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Charles Munch remains for me a recommended choice, and it has the benefit of superb RCA Living Stereo sound. Munch is one of my very favorite conductors of the twentieth century, and Piatigorsky was one of the greats as well. Some have commented on how Much and Piatigorsky were opposites, with Munch being characteristically combustible and extroverted and Piatigorsky being more reserved and brooding. Nevermind all that. They make it work marvelously, with Munch conducting with flair and spontaneity, and Piatigorsky bringing great beauty to the more inward moments but by and large keeping up with Munch. There is no doubt events alternate between the red-blooded approach of Munch and the more reflective moments of Piatigorsky. But the deciding factor for me is the incredible playing of the BSO on this recording, it is nothing short of stunning. The orchestra is rather forwardly miked, and at times I could use Piatigorsky to be closer in the sound picture.

Pierre Fournier with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra led by George Szell from 1961 on the Deutsche Grammophon label remains highly recommended. The aristocratic Fournier is a bit more inward looking than Rostropovich, but he plays beautifully and majestically. The partnership with Szell is ideal, both working in unison and riding the waves of alternating moods so well. Szell in his usual way pushes hard in some parts, but never too much, and the sense of teamwork and interchange is palpable and the sound of Fournier’s cello is captured better than Piatigorsky on the Munch recording. Then there is the Berlin Philharmonic playing like gods, with all parts of the orchestra sounding marvelous (brass are a bit distanced in spots, but no big concern). Fournier employs a singing tone so wonderfully, but never overplays his hand, leading to an introspective and yet exciting performance. A great classic recording.

One of the surprises I found on my survey is the 1974 recording on Vox by the Canadian-Russian-Jewish cellist Zara Nelsova joined by the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra and the underrated conductor Walter Susskind. Nelsova had recorded the concerto previously, but this is a joyful and lively performance buoyed by Nelsova’s naturally lyrical tone and her controlled sense of musical line. There are no tricks here, no extra emotion or sentimentality, but she finds the right balance between expression and structure. Susskind is a solid accompanist, showing the SLSO at its best, rhythmically taut but also drawing some nicely flexible phrasing out as well. The sound is good, perhaps not quite as good as the larger classical labels at the time, but still better than average. While not displacing Casals, Fournier, or Rostropovich, this is every bit as enjoyable in its way and stands alongside other more feted versions.

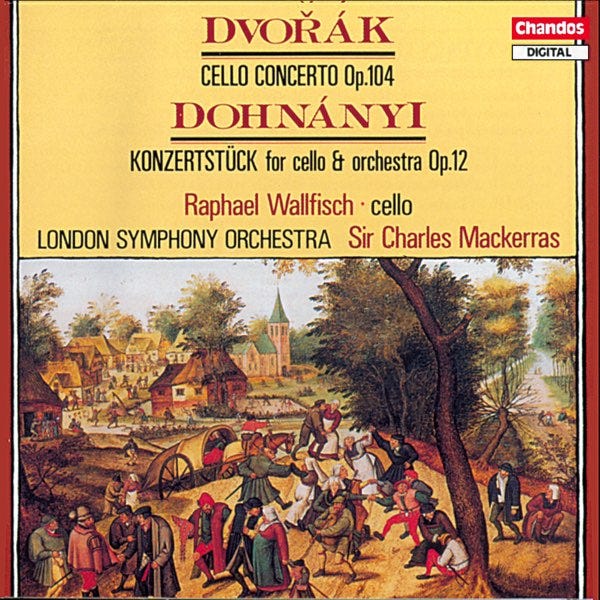

The 1988 recording from Sir Charles Mackerras and the London Symphony Orchestra with cellist Raphael Wallfisch on the Chandos label is delightful as well. Of course we have Mackerras, one of the truly great Dvořák interpreters of his generation, leading a typically idiomatic performance. The recording sounds terrific, up to Chandos’ exalted early standards, and the acoustic of St. Jude’s Church in London is detailed and generous if just a tad reverberant. Wallfisch’s performance is excellent throughout, not overly dramatic, but supremely lyrical and warm. He handles all the more virtuoso passages easily, and his tone is pure with no excessive vibrato. Wallfisch is perhaps not quite as incisive as Rostropovich or even Fournier, but still delivers a satisfying performance. The tender moments in particular are well done, and Mackerras lets the LSO off the leash for the big tuttis. Altogether this is a wonderful recording (and the Dohnányi piece on the album is well worth hearing too).

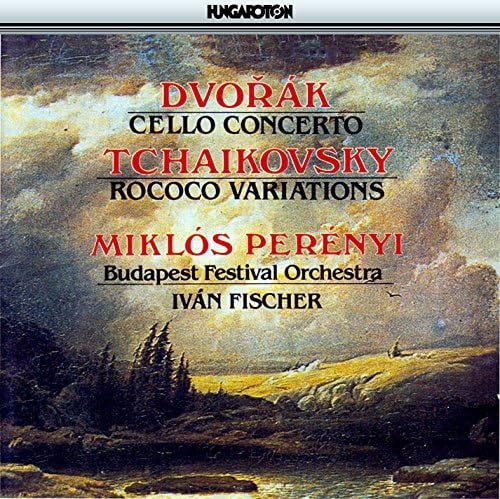

Another relatively surprising find for me was the 1994 recording from cellist Miklós Perényi and the Budapest Festival Orchestra under their long time director Iván Fischer on the Hungaroton label. The sound is wonderful, glowing and detailed. Fischer always has good ideas when it comes to Dvořák, and this recording is no exception. This is a more direct reading than Karajan or even Szell, phrases are not lingered over too long, and tempos are marginally faster than many recordings. The performance is fresh and lively, and perhaps more rhythmically alert than many. Perényi follows Fischer’s lead in moving the flow along nicely without shortchanging Dvořák’s lyrical exchanges and expressiveness. There is some mighty impressive playing here from Perényi, heartfelt but also somewhat lighter on its feet.

The 2005 recording from Jean-Guihen Queyras accompanied by the Prague Philharmonia and the late conductor Belohlávek, Jirí on Harmonia Mundi is superb and recommended in every way. Queyras has a wonderful tone and technique, and possesses a stunning virtuosity. But more than that, he is uncanny at finding and exploring the musical line and putting his own stamp on it. Moreover, his sound on the cello is never harsh or growling even in more assertive passages. Somewhat like Nelsova, Queyras doesn’t over-emote but also can draw tremendous tenderness and feeling from his instrument. Vibrato is used, but not self-consciously, and there is no shortage of power or fullness of tone in the solo passages. The Prague Philharmonia is a smaller orchestra, and as such textures are leaner and more transparent. But there is no lack of heft, and Belohlávek and Queyras are extremely attuned to one another. The interplay between soloist and orchestra is as tight and seamless as I’ve ever heard. The sound is well balanced, the whole picture slightly recessed but with no lack of weight or detail.

Also from 2005 we have Iván Fischer conducting the Budapest Festival Orchestra again, this time with cellist Pieter Wiseplwey on Channel Classics. This is a live recording, though you might not know it from the excellent sound (though applause is kept on the recording). Wispelwey always brings an intelligence and intensity to his performances, and here we get a good sense of his spontaneity in concert but also his natural musicality. His tone is not quite as deep and sonorous as Rostropovich or Fournier, but he is such a pleasure to hear. Similar to Queyras, he hardly ever makes a harsh noise. The nuance and sensitivity he brings to the solo part is delectable and unique. Fischer and the Budapest orchestra are great partners, and the blend is ideal. Fischer pays careful attention to dynamics and phrasing, as he does on his other Dvořák recordings.

The 2012 Hyperion recording with Steven Isserlis and Daniel Harding leading the Mahler Chamber Orchestra is another outstanding performance and recording, again highlighting a more modern approach using a smaller orchestra, somewhat quicker tempos, and a less grand conception overall. Recorded at the Teatro Comunale in Ferrara, Italy, Harding leads an incisive performance from the chamber sized orchestra, again emphasizing rhythmic and dynamic accents and transparent textures. Speeds are marginally faster than average. But Isserlis and Harding don’t ignore the romanticism and wistfulness in the score either. Indeed, Isserlis provides one of the most lyrical and poetic interpretations on record. But his tone is never heavy and thick, his agility on the cello is impressive, and he has just the right sense of when to quicken his pace and when to back off to bring out the more lyrical phrases. The sound is excellent.

The outstanding 2014 Decca recording featuring Alisa Weilerstein on cello with the Czech Philharmonic led by the late Czech conductor Jiří Bělohlávek remains highly recommended. The Adagio second movement is played with the utmost touch and grace, and even though the opening of the concerto’s first movement is not my favorite, the rest of the recording more than makes up for it. This is full flavored Dvořák than the Isserlis or Wispelwey, with Weilerstein’s cello coming through with a darker and fuller tone. The Czech Philharmonic has this music in their veins, and if Bělohlávek occasionally sounds like he is on auto-pilot, the accompaniment is still quite good. While I haven’t been as taken with Weilerstein’s other recordings, this one is among the best. The sound is warm, lacking some inner detail in the strings and woodwinds in a spacious acoustic.

Honorable Mention

Philharmonia Orchestra / Fournier / Kubelik (Artemisia 1948

Czech Philharmonic / Rostropovich / Talich (Pristine 1952)

Tonhalle Zurich / Tortelier / Ackermann (Datum 1952)

National Symphony Orchestra / Navarra / Schwarz (Profil 1954)

Philharmonia Orchestra / Starker / Susskind (Warner 1957)

Hamburg State Philharmonic / Hoelscher / Keilberth (Warner 1958)

London Symphony Orchestra / Starker / Dorati (Mercury 1961)

The Philadelphia Orchestra / Rose / Ormandy (Sony 1965)

Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra / du Pré / Celibidache (DG 1967)

Chicago Symphony Orchestra / du Pré / Barenboim (Warner 1971)

London Symphony Orchestra / Tortelier / Previn (Warner 1979)

Concertgebouw Orchestra / Schiff / Davis (Universal 1981)

Boston Symphony Orchestra / Rostropovich / Ozawa (Warner 1985)

Vienna Philharmonic / Schiff / Previn (Univeral 1992)

Oslo Philharmonic / Mørk / Jansons (Warner 1993)

New York Philharmonic / Ma / Masur (Sony 1995)

Taipei / Finckel / Chen (Artlisted 2003)

Indianapolis Symphony / Bailey / Märkl (Telarc 2011)

Prague Philharmonia / Moser / Hrusa (Pentatone 2015)

Moravian Philharmonic / Miranda / Vronsky (Navona 2015)

DSO Berlin / Poltera / Dausgaard (BIS 2016)

NDR Symphony Orchestra / Müller-Schott / Sanderling (Orfeo 2016)

DSO Berlin / Coppey / Karabits (Audite 2017)

Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège / Julien-Laferrière / Madaras (Alpha 2020)

Ukraine National Orchestra / Gromes / Sirenko (Sony 2024)

Philharmonia Orchestra / Kotova / Litton (Sony year not listed)

Thank you once again for reading! We have made it to the end of this installment, but join me next time when we discuss Antonio Vivaldi’s ever popular The Four Seasons. See you then!

_____________________

Notes:

Brennan, Gerald. Schrott, Allen. Stevenson, Joseph. Woodstra, Chris. All Music Guide to Classical Music, The Definitive Guide. All Media Guide. Pp. 397, 402-403 1129. Backbeat Books, San Francisco. 2005.

Clapham, John. "Antonín Dvořák, Musician and Craftsman". St. Martin's Press, New York, 1966.

Clapham, John, Dvořák. New York: Norton, 1979.

Dvořák, Antonín: Violoncellový koncert op. 104. (Violoncello e piano) Praha: Editio Bärenreiter, 2004. H 1200.

Kraemer, Uwe. Dvorak Violin Concerto and Cello Concerto. Essential Classics. 1990. Sony Classical Liner Notes. Pp. 5-6.

Lunday, Elizabeth. Secret Lives of Great Composers. Antonin Dvorak. Pp. 137-144. Quirk Books, Philadelphia. 2009.

Smaczny, Jan. Dvořák: Cello Concerto. Cambridge Music Handbooks. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999.

The Gramophone Classical Music Guide. 2010. Online at https://www.prestomusic.com/classical/products/7924179--dvorak-tchaikovsky-works-for-cello-orchestra.

Tibbets, John C. (ed.), Dvořák in America, Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1993.

Westler, Max. Strange Bedfellows. Online review at https://www.enjoythemusic.com/magazine/music/1004/classical/piatigorsky.htm.

https://en.wikipedia.org/Antonin_Dvorak

The Rostropovich/Karajan has always been my favorite. I've been listening to it since college (mid 80's). Great post, as always!

Very complete survey, almost all the great versions are here. In my opinion there are two great omission: Gendron/Haitink (one of the best) and Helmerson/Jarvi, a sleeper but a great one too. Please John, try to listen and let me know what you think