Building a Collection #92

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

By Richard Wagner

_____________________

“I believe in God, Mozart and Beethoven, and likewise their disciples and apostles.”

-Richard Wagner

Dear reader, we have arrived at #92 in our Building a Collection series, and we again encounter Richard Wagner. In this slot is his only fully mature comic opera, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. The biographical information below on Richard Wagner is edited for length, but if you would like to read more about Wagner, I refer you to one of my earlier posts here: https://open.substack.com/pub/classicalguy/p/42-richard-wagner-tristan-und-isolde?r=avz62&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

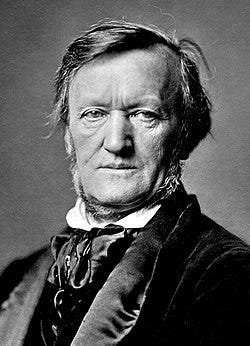

Richard Wagner (1813 - 1883)

German composer Richard Wagner was born in 1813 in Leipzig, Germany and died in 1883 in Venice, Italy. Wagner remains one of the most important, influential, and controversial composers in the history of classical music. In addition to composing, Wagner was also a theater director, conductor, and polemicist. Wagner is remembered primarily for his operas, or as he liked to call them “music dramas”. In addition to writing the music for his operas, unusually and astonishingly he also wrote the libretto for each of them. Wagner’s music is known for its rich harmonic textures, complex themes, and his extensive use of leitmotifs, defined as musical phrases associated with individual characters, places, ideas, or plot elements. Wagner is credited with contributing new ideas in music such as shifting tonal keys, his further development of chromaticism, and his innovative use of language. His opera Tristan und Isolde is often considered to be the beginning of modern music.

Of all the great composers, Wagner was one of the latest bloomers. He really didn’t begin taking a more significant interest in music until 1828 when he attended a performance of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony “Choral” at the Gewandhaus Leipzig. Wagner was indelibly impressed by this experience, and Beethoven became a lifelong inspiration. Other musical experiences that were formative include hearing Mozart’s Requiem, and a performance by dramatic soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient. Later recalling this moment Wagner wrote, "When I look back across my entire life I find no event to place beside this in the impression it produced on me," and he claimed that the "profoundly human and ecstatic performance of this incomparable artist" kindled in him an "almost demonic fire."

As a music student, Wagner was like a sponge, quickly learning everything he was taught and picking up music theory and composition extraordinarily quickly. He was largely self-taught, eventually giving up other pursuits entirely to devote himself to music. Wagner’s first opera to achieve success was Rienzi from 1842, followed by Die Fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman) in 1843 and Tannhauser in 1845. His next big opera was not until 1851 with Lohengrin, and then Tristan und Isolde was the next huge success many years later in 1865. The primary reason for the big gap in time was that during most of the 1850s Wagner was working on what would become the four operas of The Ring Cycle. In 1868 his only full-length comic opera, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, premiered at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich to resounding acclaim and is often considered his most accessible and immediately enjoyable opera (despite its length of more than four hours).

By most accounts, on a personal level Wagner was a rather loathsome man and possessed some of the most unpleasant human characteristics. Harold Schonberg in The Lives of the Great Composers says,

“There was something messianic about the man himself, a degree of megalomania that approached actual lunacy…he radiated power, belief in himself, ruthlessness, genius. As a human being, he was frightening. Amoral, hedonistic, selfish, virulently racist, arrogant, filled with the gospels of the Superman and the superiority of the German race…”

Wagner was a controversial figure during his lifetime, and that has continued to the present day. Wagner’s antisemitic thoughts and writings reflected common trends of the day in 19th century Germany. Some scholars give examples of Jewish stereotypes present in his operas, although throughout his life Wagner had Jewish friends and colleagues. In his final years, Wagner became interested in the philosophy of Arthur de Gobineau. Gobineau believed that Western society was doomed because of the miscegenation between superior and inferior races. Whether Wagner took up these beliefs, or incorporated them into his operas, is still a matter of debate.

Still other scholarly theories about Wagner exist, notably those claiming that his art was influenced by his early socialist leanings, and that there are socialist ideas present in some of his operas. There are several leftist authors that have identified Wagner as part of the left-wing German bourgeois radicalism in the mid-19th century born out of Karl Marx’s writings. If Wagner was a revolutionary while younger, it is clear he became more of a reactionary in his older age, wanting to uphold the order that he had once railed against.

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

Wagner’s opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg is a music drama in three acts and is one of the longest single operas commonly performed at major opera houses in the world today. A typical performance runs about four and a half hours, and the opera is rarely cut or abbreviated. Die Meistersinger is rather unique among Wagner’s operas in that it is the only comedy among his major operas, and is set at a defined historical time and place whereas many of operas are based on legend or myths. It is based on an entirely original story, and unlike Wagner’s other operas it contains no references to the supernatural or mythology. The opera even contains several musical devices which Wagner generally criticized such as arias, choruses, ensemble numbers, and ballet music.

The genesis of the opera stems from Wagner’s own reading of German literary commentator Georg Gottfried Gervinus’ book on the History of German Poetry. Gervinus discusses a real historical figure by the name of Hans Sachs (1494-1576) who was legendary because he was considered the most prominent Meistersinger (Master Singer) and craftsman of the city of Nürnberg. At the time Nürnberg was considered one of the great centers of Renaissance art and music, and Wagner became fascinated with the guild of Meistersingers, an amateur association of musicians all of whom were also traditional craftsmen from various trades. Wagner used Sachs as a main character as he was the most famous of all Meistersingers and by also incorporating singing contests into the story, as well as some of Sachs’ own poetry in the libretto. Wagner first worked on a draft of his story in 1845.

Wagner was also profoundly influenced by the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, in particular his ideas about aesthetics. The philosophy says that art is essentially an escape from the world, and furthermore that music is the highest of the arts since it is the most abstract and is able to represent the world and human emotions without words. Wagner’s Die Meistersinger articulates the composer's ideas on many aspects of society, namely the importance of the human will and our tendency to deceive ourselves about reality (this takes the form of mistaken identity in Act II of the opera). In Act III, Sachs’ monologue Wahn, Wahn, überall Wahn (Madness! Madness! Everywhere madness!) is an idea from Schopenhauer about how self-delusion can ultimately lead us to self-destructive behavior.

Wagner once again began working on Die Meistersinger in 1861, complete with these additional thoughts influenced by Schopenhauer. Indeed, as Wagner scholar Lucy Beckett notes, the character of Sachs is very similar to Schopenhauer’s description of the “noble man”:

“We always picture a very noble character to ourselves as having a certain trace of silent sadness... It is a consciousness that has resulted from knowledge of the vanity of all achievements and of the suffering of all life, not merely of one's own.”

In rejecting the prospect of becoming Eva’s husband in the opera, Sachs also takes on another key idea from Schopenhauer, that of denying his own will for higher ideals.

Even though Wagner had completed the Prelude by 1862, the complete opera was not finished until 1867. During those years Wagner endured some of his most devastating personal setbacks which significantly contributed to the delay. Finally the premiere was given on June 21, 1868 at the Königliches Hof- und National-Theater in Munich, conducted by Hans von Bülow. The premiere was a great success, and the audience called for Wagner himself to stand from the Royal box where he had been seated with the work’s sponsor, King Ludwig II of Bavaria. Wagner allegedly broke royal protocol by bowing, something only the King was permitted to do.

The list of roles in the opera is extensive:

Eva, Pogner's daughter - soprano

David, Sachs's apprentice - tenor

Walther von Stolzing, young knight from Franconia - tenor

Sixtus Beckmesser, town clerk, mastersinger - baritone

Hans Sachs, cobbler, mastersinger - bass-baritone

Veit Pogner, goldsmith, mastersinger - bass

Supporting roles:

Magdalena, Eva's nurse - soprano

Kunz Vogelgesang, furrier, mastersinger - tenor

Balthasar Zorn, pewterer, mastersinger - tenor

Augustin Moser, tailor, mastersinger - tenor

Ulrich Eisslinger, grocer, mastersinger - tenor

Fritz Kothner, baker, mastersinger - baritone

Nachtwächter, or Nightwatchman - bass

Konrad Nachtigall, tinsmith, mastersinger - bass

Hermann Ortel, soapmaker, mastersinger - bass

Hans Foltz, coppersmith, mastersinger - bass

Hans Schwarz, stocking weaver, mastersinger - bass

Citizens of all guilds and their wives, journeymen, apprentices, young women, people of Nuremberg

Synopsis

The synopsis of the opera from the Metropolitan Opera is a helpful guide:

ACT I

Nuremberg, 16th century. At St. Katherine’s Church, the visiting young knight Walther von Stolzing approaches Eva, daughter of the wealthy goldsmith Pogner, who is attending mass with her companion, Magdalene. Eva tells her admirer that she is to be engaged the following day to the winner of a song contest held by the local guild of mastersingers. David, Magdalene’s sweetheart and apprentice to the cobbler and mastersinger Hans Sachs, explains the rules of song composing to Walther, who is surprised by the complicated ins and outs of mastersinging. Meanwhile David’s fellow apprentices set up for a preliminary trial singing. The masters arrive, including Eva’s father, and Walther expresses his desire to become a mastersinger in order to ask for Eva’s hand. The town clerk Beckmesser, a spiteful pedant who also wants to marry Eva, is immediately suspicious of the young knight. As proof that tradesmen value art, Pogner offers his daughter’s hand as the prize for the next day’s contest and explains that she can reject the winner, but must marry a mastersinger or can marry no one. Walther introduces himself and describes his natural, self-taught methods of musical composition, provoking mocking comments from Beckmesser. For his trial song, Walther sings an impulsive tune in praise of love and spring, breaking many of the masters’ rules. Beckmesser vigorously keeps a count of his errors. Rejected by the masters, Walther leaves, while Sachs wonders about the unexpected appeal of Walther’s song.

ACT II

That evening in front of Pogner’s house, David tells Magdalene about Walther’s misfortune and Eva gets the disappointing news from Magdalene. Across the street, Sachs sits down to work in his doorway, but the memory of Walther’s song distracts him. Eva appears, hoping to learn more about the knight’s trial. When Sachs mentions that Beckmesser hopes to win her the next day, she suggests she wouldn’t be unhappy if Sachs himself won the contest. Sachs, who has known Eva since she was a child, responds with paternal affection. Asked about Walther, he pretends to disapprove of the young man, which leads Eva to reveal her true feelings and to run off. In the street, she is met by Walther who convinces her to elope. The two hide as a night watchman passes. Sachs, who has overheard their conversation, decides to help the lovers but prevent their flight. He lights the street with a lantern, forcing Eva and Walther to stay put. Meanwhile Beckmesser arrives to serenade Eva. As he is about to begin, Sachs launches into a cheerful cobbler’s song, much to the clerk’s irritation, claiming he needs to finish his work. They agree that both would make progress if Beckmesser were to sing while Sachs marked any broken rules of style with his cobbler’s hammer. Beckmesser finally sings his song, directing it at Magdalene who is impersonating Eva at a window of Pogner’s house. Sachs frequently interrupts with hammer strokes, to Beckmesser’s mounting anger. Walther and Eva observe the scene from their hiding place, bewildered at first, then amused. Confusion increases when David appears and attacks Beckmesser for apparently wooing Magdalene. Finally the night-shirted neighbors, roused from sleep, join in the general tumult until the sound of the night watchman’s horn disperses them. Pogner leads Eva inside while Sachs drags Walther and David into his shop. The night watchman passes through the suddenly deserted street.

ACT III

The next morning in Sachs’s workshop, David apologizes for his unruly behavior. Alone, Sachs reflects on the world’s madness. Walther arrives to tell Sachs of a wondrous dream he had. Recognizing a potential prize song, Sachs takes down the words and helps Walther to fashion them according to the rules of mastersinging. When they leave to dress for the contest, Beckmesser appears. He notices Walther’s poem and, mistaking it for one of Sachs’s own, pockets it. The returning cobbler tells him to keep it. Certain of his victory with a song written by Sachs, Beckmesser leaves. Now Eva arrives, pretending there is something wrong with her shoe. Walther returns, dressed for the festival, and repeats his prize song for her. Eva is torn between her love for Walther and her affection for Sachs, but the older man turns her towards the younger. When Magdalene arrives, Sachs promotes David to journeyman and asks Eva to bless the new song. All five reflect on their happiness—Sachs’s tinged with gentle regret—then leave for the contest.

Guilds and citizens assemble in a meadow outside the city. The masters enter and the people cheer Sachs, who responds with a moving address in praise of art and the coming contest. Beckmesser is the first to sing. Nervously trying to fit Walther’s verses to his own music he makes nonsense of the words, earning laughter from the crowd. He furiously turns on Sachs and runs off. Walther then steps forward and delivers the song. Entranced, the people proclaim him the winner, but Walther refuses the masters’ necklace. Sachs convinces him to accept—tradition and its upholders must be honored, as must those who create innovation. Youth and age are reconciled, Walther has won Eva, and the people once again hail Sachs.

After the premiere the famously sharp-tongued critic Eduard Hanslick wrote:

"Dazzling scenes of colour and splendour, ensembles full of life and character unfold before the spectator's eyes, hardly allowing him the leisure to weigh how much and how little of these effects is of musical origin."

Within a short time the opera was being performed all over Germany and in Vienna. Ironically, the opera became a symbol of German pride and unity despite the opera’s own commentary about the dangers of cultural self-regard. Sachs’ warning toward the end of the opera on the need to protect German art from foreign intervention became a point of emphasis for German nationalism. Although it took some time for the opera to catch on with foreign audiences, it did eventually spread throughout Europe by 1882 and premiered in the United States in 1886.

Die Meistersinger was unfortunately often used by the Nazis for propaganda purposes. In 1933 at the founding of the Third Reich, the opera was performed live with Hitler in attendance. In the 1935 Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will by Leni Riefenstahl the Prelude to Act III is played while footage of Nuremberg is shown during the Nazi party congress of 1934. During the war years of 1943 and 1944, Die Meistersinger was the only opera actually performed at the Bayreuth Festival. A further oddity involving Die Meistersinger occurred in 1956 when the opera was staged for the first time at Bayreuth since the end of World War II. The production by Wieland Wagner, Wagner’s grandson, was presented in an abstract staging which distanced the opera as far as possible from German nationalism by removing any hint of Nuremberg from the scenery, thereafter dubbed Die Meistersinger ohne Nürnberg (The Mastersingers without Nuremberg).

The character of Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger has frequently been decried by many Wagner scholars as a Jewish stereotype, and some claim that Beckmesser’s humiliation in the opera at the hands of the Aryan Walther is a prime example of Wagner’s antisemitism. Even members of Wagner’s family have admitted they believe he intended Beckmesser’s character to be an antisemitic trope. But it is still a controversial topic, and other scholars have theorized Wagner meant Beckmesser to represent academic pedantism in general. Still others point out that Beckmesser’s name in Wagner’s original draft was “Veit Hanslich”, and that Wagner actually meant for the character to mock the famed music critic of the time Eduard Hanslick. Hanslick was known to dislike Wagner and his music (although as mentioned before he praised Die Meistersinger), and Wagner is known to have made derogatory comments about Hanslick’s Jewish background.

I am not an expert on Wagner’s operas, but from a purely musical perspective I admit to having a hard time with Wagner’s operas. But Die Meistersinger is more accessible opera than any other Wagner opera, and for me is more enjoyable musically. The Prelude is one of my absolute favorite overtures ever composed, and is a brilliant piece of music on its own. Wagner’s use of arias, choruses, and ensemble numbers is another reason that Die Meistersinger is among his best loved operas despite its length.

Recommended Recordings

As I have with other opera recordings on the survey, along with my own impressions from listening to recordings I have turned to Ralph Moore from MusicWeb International for assistance with my recommendations for Die Meistersinger.

The first recording I recommend is from 1944 conducted by Karl Böhm. Böhm was a distinguished Wagner conductor, and this early live mono recording on the Preisler label (and other labels) was apparently made on metal tape which was entirely new at the time. The sonic results are impressive for the 1940s, and despite the fact this recording was made near the end of the Third Reich it is a satisfying performance which features some of the finest Wagner voices of the day. I would point to Paul Schöffler as Sachs and Irmgard Seefried as Eva for particular praise. Schöffler has a warm and rounded tone with depth and character, and Seefried is appropriately feminine sounding and confident throughout. Erich Kunz as Beckmesser is equally fine, his lovely voice paired with a keen vocal acting ability. The Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and Vienna State Opera Chorus are especially fine, on point and energetic.

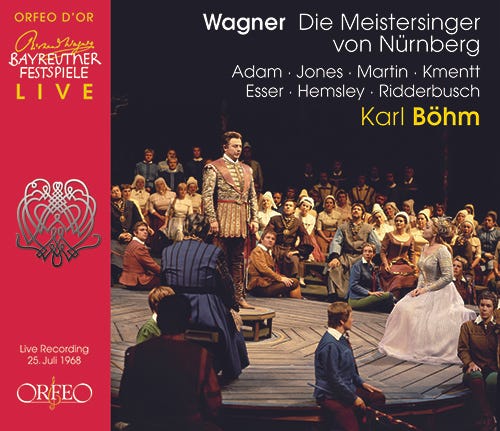

Böhm clearly felt a strong connection to Die Meistersinger, and his live stereo Bayreuth recording from 1968 on the Orfeo label is further evidence. The sound is terrific, perhaps the best sounding production ever from Bayreuth, full and vibrant. Böhm leads the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra and Chorus. Gwyneth Jones as Eva is an interesting choice, her voice perhaps rather large for the role, but she is impressive throughout. Karl Ridderbusch as Pogner is in fine form, and a young Kurt Moll as the Night-watchman is unparalleled. Thomas Helmsley as Beckmesser is ideally satirical and comical, and he sings his significant role well. Theo Adam doesn’t have the perfect voice for Sachs, as he is missing some depth and resonance. However, he characterizes the role very well and is undeniably musical in what can be a strenuous role for anyone. Böhm’s conducting is superb, sparkling, and nicely paced. Recommended.

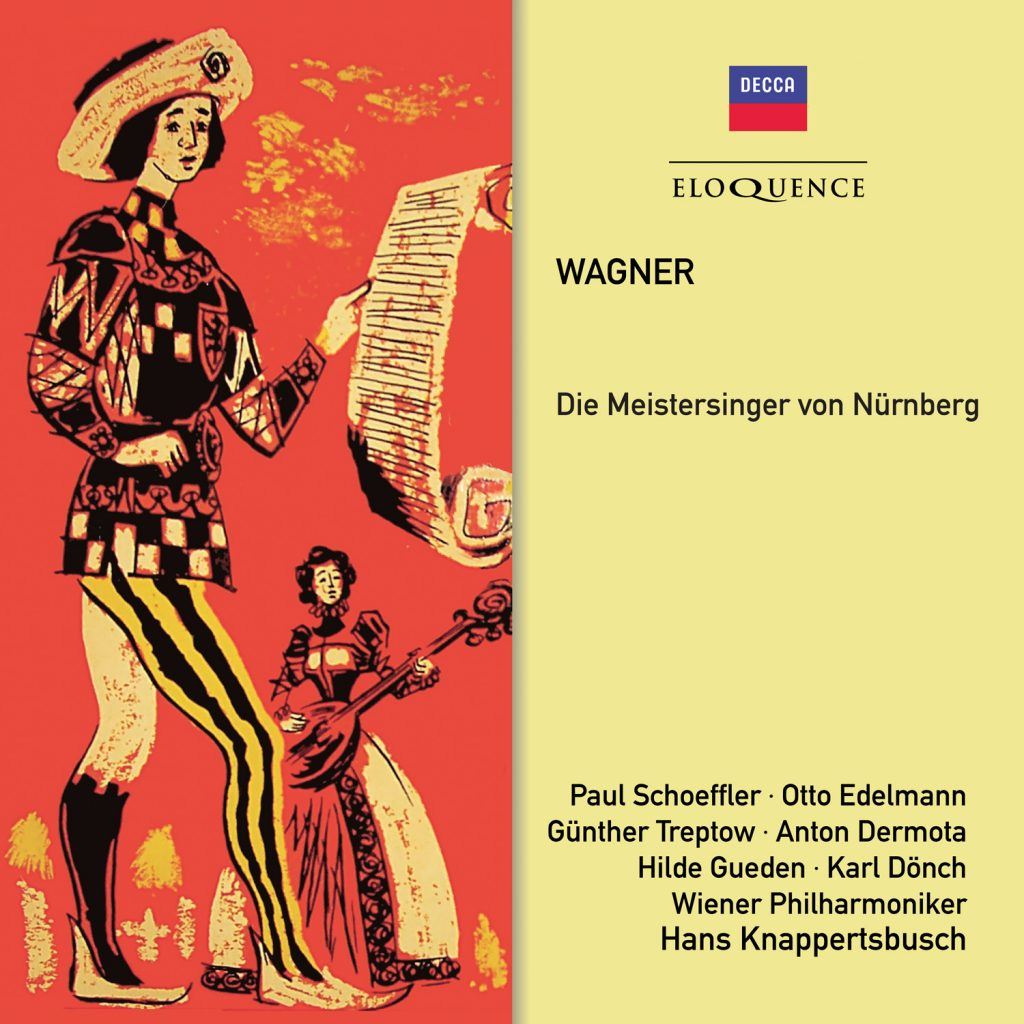

German conductor Hans Knappertsbusch was a specialist in the music of Wagner, Bruckner, and Strauss. His opera recordings, particularly those from the 1950s, are almost invariably worth investigating. While he eventually developed a reputation for some odd interpretive decisions, and while he did not fully embrace the recording medium blossoming at the time, there is no doubt he was a first-rate Wagner conductor. In the case of Die Meistersinger, he left us two recordings which are recommended. The first is a mono studio recording from 1950-51 on Decca made with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and Vienna State Opera Chorus, the first ever studio recording of the complete opera. The acoustic is somewhat tubby and thin sounding, but perfectly listenable. Once again we hear Paul Schöffler in the role of Sachs, and he is again in glorious voice. Hilde Güden’s tone as Eva is shining, and Otto Edelmann as Pogner is very good. Tristan Günther Treptow as Walther sings dramatically and effectively, even if his tone is a bit harsh. Altogether, this is a fine production.

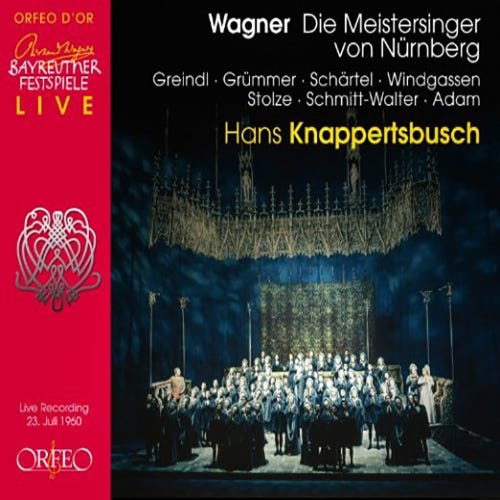

Knappertsbusch’s second recommended recording on the list is a live production from 1955 on the Orfeo label, this time in Munich. He leads the Bavarian State Opera Orchestra and Chorus, and they enjoy better sound than the 1951 set. Knappertsbusch really blazes through the Prelude, something that sets the tone for the entire performance. The casting of Lisa della Casa is noteworthy, as she brings a rare brilliance and clarity to the role of Eva. Ferdinand Frantz as Sachs is fully up to the challenge, and while a few notes are strained, as a whole he is a big asset to the set. Gottlob Frick as Pogner is excellent, and Hans Hopf as Walther is less than subtle but also perfectly fine. The Bavarians play with real gusto here, and they seem to match the energy of the cast all the way along. Knappertsbusch’s direction here seems marginally more vital than the earlier Decca set, and if I had to choose one it would be this live set from Munich.

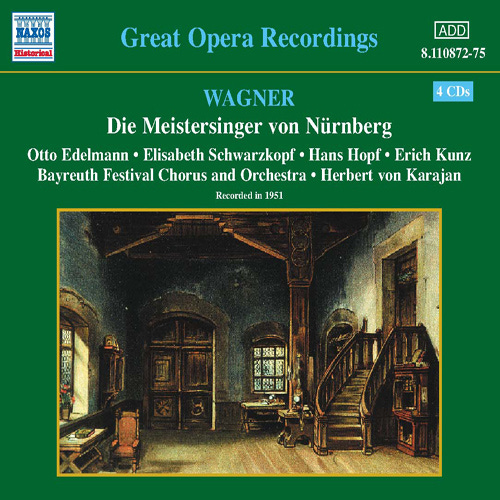

Superstar conductor Herbert von Karajan was a mere 43 years of age when he recorded his live mono 1951 Die Meistersinger at Bayreuth, now available on the Naxos, MYTO, and EMI (Warner) labels. Karajan leads the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra and Chorus in a recording that many believe is Karajan’s best of this opera. The sound is on the boomy and over-resonant side with some glare on top (mitigated somewhat on the Naxos version I heard), but not bad considering the year and source. First, I should say that Karajan was a consummate Wagner conductor, and he almost always found the right mood and pacing for his performances. Otto Edelmann is quite good as Sachs, delivering the top notes without a hint of strain and with the ability to characterize the role as well as anyone. You won’t find a more famous or more refined Eva than Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, and while I may prefer della Casa or Janowitz, she does a very nice job with the role. Hans Hopf is not my favorite Walther as he rarely varies his tone, but he does not detract. Erich Kunz brings an excellent voice to Beckmesser, even if he somewhat under-characterizes the role for my taste. Karajan builds a lot of drama, and leads a more smiling performance than you might expect.

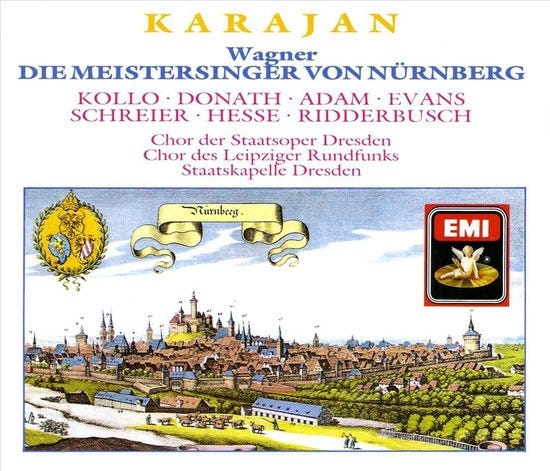

Yet another recommended recording from Karajan is the celebrated Dresden version on EMI (Warner) from 1970. In considerably better sound than the historic version above, Karajan leads the Staatskapelle Dresden along with the Dresden Opera Chorus and the Leipzig Radio Chorus. It is a beautiful sounding recording, and features some of the best Wagner voices of the time. Theo Adam is cast as Sachs this time, and while he does not rival the best, his performance is fully in character and Adam knew how to use his voice to best effect. Helen Donath as Eva is excellent, with both weight and sweetness in her voice. Kurt Moll is the Night-watchman once again, certainly one of the finest voices ever in the role. René Kollo is captured early in his career as Walther, and although his voice is not terribly appealing, he delivers the essence of the role. Karl Riddersbusch is very fine again as Pogner. The Beckmesser of Geraint Evans is perhaps the only blemish on the set, his voice and characterization being nothing short of grating. Karajan shines in his overall interpretation, and the orchestral and choral contributions are very well done. I had trouble finding this recording on streaming services, which is a mystery to me as to the reason. But I found it easily on YouTube.

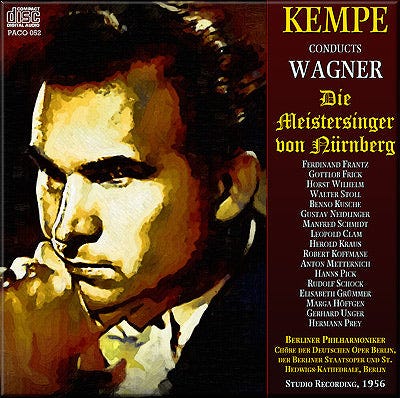

The often underrated and overshadowed Rudolf Kempe was an excellent Wagner conductor, and his 1956 recording with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Deutsche Opera Berlin Chorus, Staatskapelle Berlin Chorus, and the St. Hedwigs Cathedral Chorus for EMI (Warner) and now on the Pristine label, remains one of the most recommendable versions. We hear the very fine Ferdinand Frantz as Sachs, the crystal clear and pure Elisabeth Grümmer as Eva, and the veteran Gottlob Frick as Pogner. Rudolf Schock as Walther is good, if not particularly distinguished. Gustav Neidlinger and Gerhard Unger are among the best on record in their roles, and while the Beckmesser of Benno Kusche is too over the top, he does not detract from an otherwise excellent production. Kempe finds the warmth and humor in the score, and is able to be incisive when needed. The BPO plays beautifully here, and the choral contributions are satisfying and full. In summary, this is another excellent historic recording of this opera.

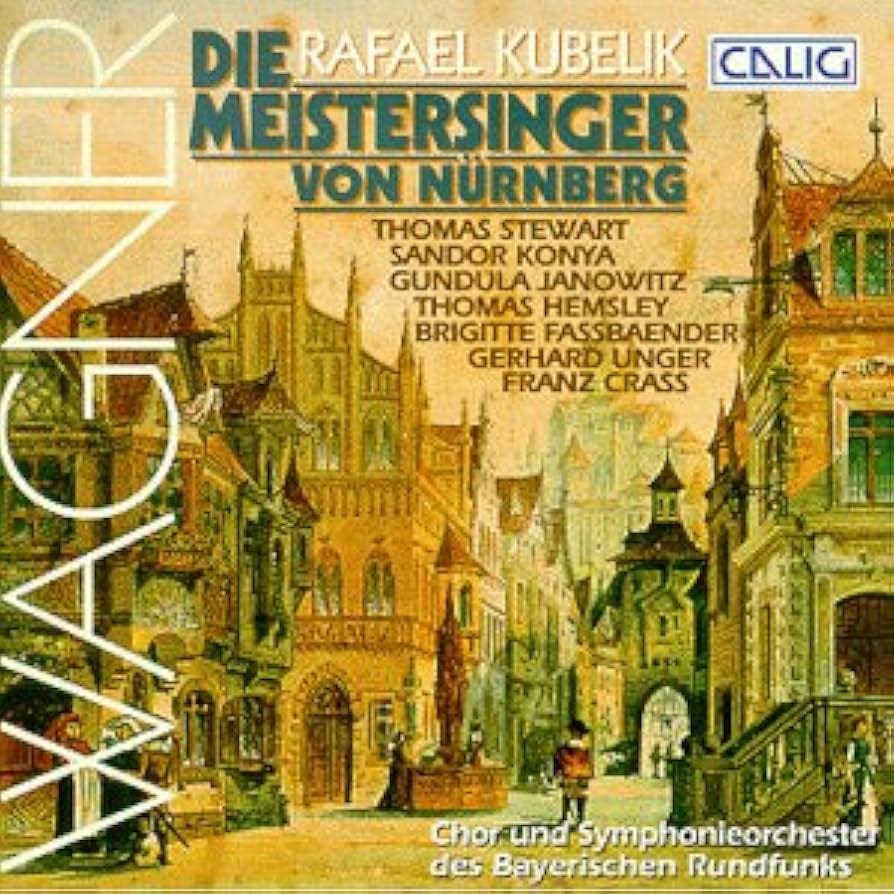

Legendary Czech conductor Rafael Kubelik led an outstanding live account of Die Meistersinger in 1967 with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, available on several labels (the best sounding one being on the Calig label) but not currently on audio streaming services. I easily found it on YouTube. The sound is astonishingly good for a live radio broadcast, the Prelude jumping out at you and rarely sounding so good. Kubelik could do wonders with Wagner (as well as Dvořák and Mahler), and this is a terrific example of his touch. Thomas Stewart as Sachs and Gundula Janowitz as Eva are at the top of their class in these roles, both among the finest on record. Sándor Kónya as Walther is very good, and the rest of the cast is at least as good as any others on the list. The ensemble singing, especially the famous Quintet from Act III, is exceptional. The BRSO and Chorus sound extraordinarily good. This one is certainly a top recommendation.

The most recent recording in my recommended list is 1975-76 with Sir Georg Solti leading a studio recording with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus of the Vienna State Opera on Decca. Of course, we are blessed with excellent sound on Decca from the old Sofiensaal in Vienna. This recording reasserts Solti’s gift for conducting Wagner, and he was certainly one the greatest Wagner conductors of the 20th century. But it also comes down to the primary voices, and here we have a wonderful Sachs in Norman Bailey. I’ve always been a fan of Kurt Moll’s warm, resonant voice and here he is very effective as Pogner. Bernd Weikl is also animated and effective as Beckmesser, and René Kollo is good (if not great) as Walther. The weakest link in the main voices is Hannelore Bode as Eva, and while she is not in the same league as others mentioned in this survey, she is at least decent. The VPO sounds rich and warm, and even though Solti’s pacing is on the relaxed side, he rises to the occasion where needed. This is preferable to his later 1995 recording in most aspects, although that one shows up below in my honorable mention list.

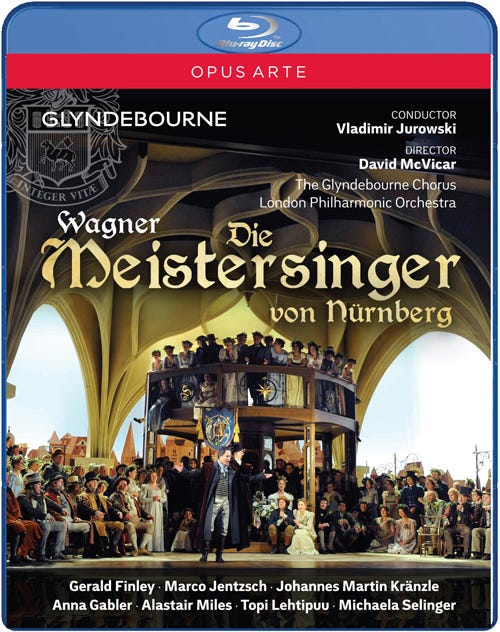

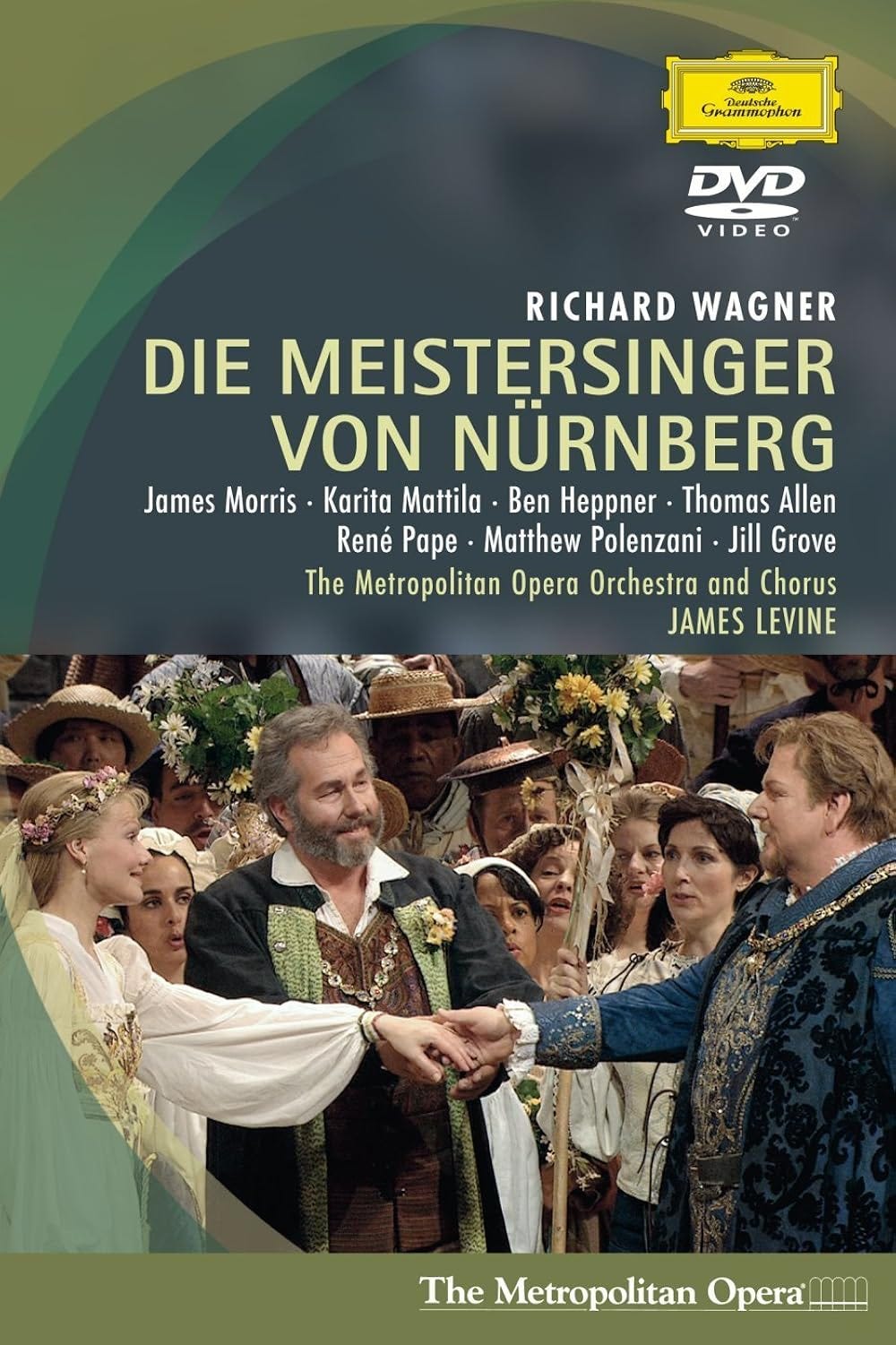

If you are looking for a video production of Die Meistersinger, I recommend the 2011 Glyndebourne recording led by Vladimir Jurowski on the Opus Arte label. Gerald Finley is quite good as Sachs, and Alastair Miles as Pogner is in good voice. The Eva of Anna Gabler is fine, although not up to the best I’ve heard in the role. David McVicars staging is one of the selling points here. His production is unique and clever, and he pokes fun at politics and social conventions in subtle, yet unmistakable ways. Jurowski conducts the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Glyndebourne Chorus and his direction is especially incisive and pointed, and the playing has a clarity and momentum rarely heard in this opera. It works marvelously. The 2004 Metropolitan Opera production with James Levine on Deutsche Grammophon is also worth exploring with a starry cast including Ben Heppner, James Morris, Karita Mattila, Rene Pape, and Thomas Allen. I have only seen clips of some of the major numbers, but in what I have seen the singing is very fine. Levine’s conducting is sometimes criticized for lacking intensity and being too leisurely. But you can decide for yourself if you are interested.

Honorable Mention Recordings

Vienna Philharmonic / Toscanini (Andante 1937)

Dresden Staatskapelle / Kempe (Profile 1951)

Bayreuth Festival / Cluytens (Walhall 1957)

Metropolitan Opera / Schippers (Sony 1972)

Bayreuth Festival / Varviso (Universal 1974)

Deutsch Opera Berlin / Jochum (DG 1976)

Bavarian State Opera / Sawallisch (Warner 1993)

Chicago Symphony and Chorus / Solti (Decca 1995)

Bayreuth Festival / Barenboim (Warner 1999)

Staatskapelle Dresden / Thielemann (Profil 2020)

See you next time when we will discuss #93: Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. See you then!

______________

Notes:

Bogart, Richard S. (7 May 2012). "Die Meistersinger: Performance History". OperaGlass. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

Carnegy, Patrick (1994). "Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg". Cambridge Opera Handbooks (in German). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44895-6.

Gregor-Dellin, Martin (1983) Richard Wagner: his life, his work, his Century. William Collins, ISBN 0-00-216669-0 page 376.

Lee, Patrick (2014). "The Mastersingers of Nuremberg and St Catherine's Church". Retrieved 13 December 2014.

Lunacharsky, Anatoly (1965) [1933]. "Richard Wagner (On the 50th Anniversary of His Death)". On Literature and Art. Translated by Pyman, Avril. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Magee, Bryan (2002). The Tristan Chord. New York: Owl Books. ISBN 0-8050-7189-X. (UK title: Wagner and Philosophy, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-029519-4)

Magee, Bryan (2000). Wagner and Philosophy. London: Allen Lanes. ISBN 978-0-7139-9480-3.

Moore, Ralph. Wagner’s Die Meistersinger: A partial discographical survey. Online at https://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2018/Dec/Wagner_Meistersinger_survey.pdf.

Millington, Barry (ed.) (1992). The Wagner Compendium: A Guide to Wagner's Life and Music. Thames and Hudson, London. ISBN 0-02-871359-1 p. 304.

Newman, Ernest (1976). The Life of Richard Wagner (4 vols.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schonberg, Harold C. The Lives of the Great Composers (Revised Edition). Pp. 274-277. W. W. Norton & Company, New York. 1981.

Schopenhauer, Arthur. The World as Will and Presentation. The Longman Library of Primary Sources in Philosophy. Volume I, ISBN 0-321-35578-4. Volume II, ISBN 978-0275967147.

Tenenbom, Tuvia. "Hallo, Herr Hitler!", Die Zeit, August 13, 2009.

Vazsonyi, Nicholas (19 May 2018). Wagner's Meistersinger: Performance, History, Representation. University Rochester Press. ISBN 9781580461689. Retrieved 19 May 2018 – via Google Books.

von Westernhagen, Kurt (1980). "(Wilhelm) Richard Wagner". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 20. London: Macmillan Publishers.

"Wagner Operas – Productions – Die Meistersinger, 1956 Bayreuth". Wagneroperas.com. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

Wagner, Richard (1911). Family Letters of Richard Wagner. Translated by Elli, William Ashton. London: Macmillan. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-8443-0014-6.

Wagner, Richard (1992). My Life. Translated by Gray, Andrew. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80481-6.

Warrack, John (1994). Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Cambridge Opera Handbooks. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44895-6.

https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/13890.Richard_Wagner?scrlybrkr=40ad99ec.

https://www.metopera.org/discover/synopses/die-meistersinger-von-nurnberg/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Die_Meistersinger_von_N%C3%BCrnberg?scrlybrkr=40ad99ec

![Wagner - Bailey, Kollo, Bode, Hamari, Weikl, Moll, Wiener Philharmoniker, Sir Georg Solti – Die Meistersinger Von Nürnberg – Box Set 4 x CD, [r11408947] | Discogs Wagner - Bailey, Kollo, Bode, Hamari, Weikl, Moll, Wiener Philharmoniker, Sir Georg Solti – Die Meistersinger Von Nürnberg – Box Set 4 x CD, [r11408947] | Discogs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!1E4L!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5cc3c372-627f-46ad-a7aa-ce08da08f763_600x513.jpeg)