Building a Collection #91

Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85

By Edward Elgar

____________

“I believe in the power of music to bring people together, to heal, and to inspire.”

-Edward Elgar

As we continue our survey of the top 250 classical works of all-time, we come once again to English composer Edward Elgar. At #91 is Elgar’s poignant and emotive Cello Concerto, certainly one of the most famous works ever composed for the cello. Elgar is one of my favorite composers, and his Cello Concerto reminds us of how he could take us to the very heart of what it means to be human. The concerto’s staying power, and its ability to speak directly to us in our modern world is a great gift.

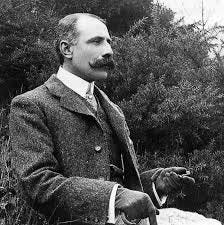

Edward Elgar (1857 - 1934)

Sir Edward Elgar was born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, England in 1857. Almost completely self-taught, Elgar spent his first forty-two years as a relative unknown. In England at the time, Elgar did not fit the role of a great composer. He was from a rural part of the country rather than one of the cities, he was not an eccentric type (indeed he was a devout Roman Catholic), and he had no musical connections that would have made his road easier. If you had seen Elgar in those days you would have noticed a distinguished-looking country gentleman, tall with a thick moustache, and piercing eyes. It was said that you could easily read Elgar’s mood from his eyes, and he carried himself with dignity.

But beginning in 1899, Elgar experienced several successes one after another which brought him not only national but international acclaim. His first big success was the Enigma Variations, followed by The Dream of Gerontius, Sea Pictures, Pomp and Circumstance Marches (no doubt you are familiar with from your high school or college commencement exercises), In the South, Introduction and Allegro for Strings, Symphony no. 1, the Violin Concerto, Symphony no. 2, Falstaff, and a series of chamber works. This string of successes lasted until about 1919.

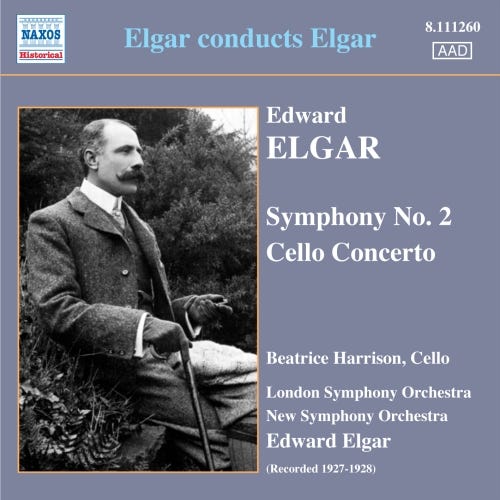

When Elgar’s wife Alice passed away in 1920, he was devastated. Thereafter, Elgar was rather lost and his attention was diverted away from composing toward other hobbies. Furthermore, the trends in classical music were most decidedly progressing on from Elgar’s neo-classical and romantic notions. He enjoyed attending the horse races, and he kept a homemade chemistry lab in his back yard. Elgar was one of the first composers to take advantage of the developing gramophone technology, and after 1926 he began recording many of his works. While he had been interested in the medium for many years, the advent of electrical microphones was revolutionary. Works which Elgar recorded included the Enigma Variations, Falstaff, Symphonies 1 & 2, and the Cello and Violin Concertos. When several of these recordings came to light much later in the century, listeners were astonished at some of the fast tempos he employed for his own works, certainly quicker than had become the norm.

While he had been a devout Roman Catholic most of his life, when inoperable colon cancer was detected in 1933, he told his doctor that he had no faith in an afterlife stating, "I believe there is nothing but complete oblivion”. He died in February 1934 at the age of 76 and is buried at St Wulstan's Roman Catholic Church in Little Malvern, Worcestershire.

Cello Concerto

By the time Elgar began work on his Cello Concerto in 1919, he had established himself as one of the most famous of all English composers. By 1918 England was already four years into the Great War. In 1917 Elgar and his beloved wife Alice had moved to a cottage in Sussex in the south of England to find some quiet amid the war, and because Elgar felt he did all his best composing while being close to nature. In fall 1918, his wife Alice commented in her diary that Edward was working on, “wonderful new music, real wood sounds & other lament which should be in a war symphony”. It was almost certainly the Cello Concerto Elgar was working on at the time, not a war symphony. The work was given its premiere about a year later in October 1919 in London with Elgar himself conducting the London Symphony Orchestra. Another year later his beloved wife Alice died, and Elgar composed very little of significance after her death.

The concerto itself is in four movements rather than the traditional three, a structure that followed Brahms’ pioneering four movement Piano Concerto no. 2. But in this case, Elgar uses the four movements to depict contrasting moods. The opening statement transitions to a Moderato theme which is brooding and full of anguish. It is followed by an Allegro Molto that finds the cello soloist faced with the most demanding and virtuoso passages that move continuously. The third movement Adagio is essentially a song for cello, while the final movement moves from Allegro to Moderato again, and finally Allegro, ma non troppo. While there is an undeniable autumnal feeling to the work, and the main themes that recur throughout are somewhat wistful and melancholy, there are also playful and energetic passages. The movements are fairly concise, and the bold and dramatic opening statement on solo cello returns again changed in the scherzo, and then returns again toward the end of the finale before the headlong dash to the end.

There can be little doubt of the concerto’s stormy and wrenching emotions being Elgar’s depiction of the destruction and aftermath of the war. This was somewhat at odds with Elgar’s previous rather Edwardian style. Elgar already suffered from bouts of extreme self-doubt, and coupled with his natural style falling out of favor, it left him in a crisis. The day after having his tonsils removed in 1918 Elgar wrote out the melody in his head that would eventually become the main theme of the concerto. As it developed it was clear that the work was darker, more somber, and even mournful. Granted there are moments of reprieve such as the Adagio, which is thoroughly and utterly Elgarian in its flavor. It is a very emotional work, at times bordering on schmaltz, but ultimately more poignant and meaningful than any other work Elgar would compose. Of course the cello itself lends itself well to emotive and expressive music, being one of the most distinctive and beautiful of stringed instruments.

The premiere in 1919 was a notable disaster, with Elgar conducting a poorly rehearsed London Symphony Orchestra, prompting one prominent critic to declare, “never, in all probability, has so great an orchestra made so lamentable an exhibition of itself”. For a while the work did not receive its due, but eventually it worked its way into the repertoire and then after the legendary recording (see below) and live performances of the work by Jacqueline du Pré, the work has since been considered one of the truly great works for cello and orchestra.

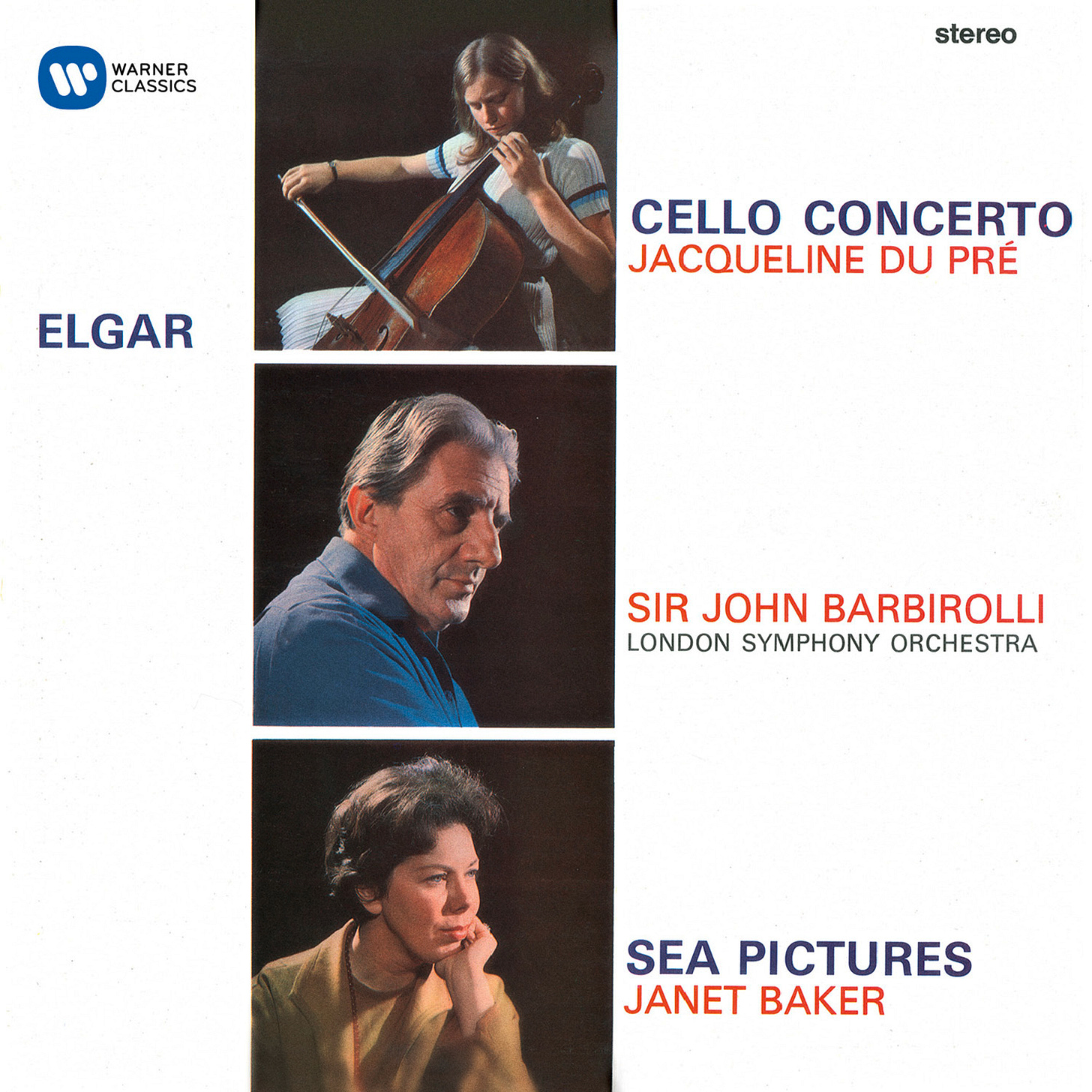

The Essential Recording

The essential recording for Elgar’s Cello Concerto is a nearly unanimous choice, that being the 1965 recording by English cellist Jacqueline du Pré accompanied by the London Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Sir John Barbirolli on the EMI(Warner) label. Recorded in August 1965 (when du Pré was only 20 years of age!) at Kingsway Hall in London, it still sounds terrific and it caught the London Symphony Orchestra during one of the very finest periods in their history. One of the interesting facts about this recording is that 19 year-old John Barbirolli himself played in the cello section of the LSO under Elgar himself when the work was premiered in 1919. It is known that Barbirolli had a deep connection to the work.

But it is du Pré that makes this recording so special. She plays this piece like no other cellist ever has, or possibly ever will. This is an unabashedly passionate and romantic account where she and the orchestra pull out all the stops to present the work as both tragic and transcendent. Sadly, du Pré’s career was cut short by multiple sclerosis, and she died at the age of 42. Perhaps knowing her tragic story, we listen with different ears to her playing? Or perhaps du Pré just had a special affinity with the piece. In any case, what we hear is playing of true emotional depth and breathtaking virtuosity. This recording brought the cellist international recognition, and it has remained the benchmark ever since. Barbirolli and the LSO provide full and idiomatic accompaniment.

Recommended Recordings

The concerto has been quite well served on record, particularly in more recent years, and there are many excellent recordings to choose from among those available. I will list my favorites, and then please explore the honorable mention list as well which contains some additional high-quality performances.

As noted above, Elgar was interested in the possibilities of gramophone recordings early on. Elgar himself was to conduct the first complete recording of the concerto in 1928 for EMI (Warner) and Naxos with the New Symphony Orchestra of London with soloist Beatrice Harrison on cello. The sonic limitations are immediately obvious, but the recording is valuable not just for historical reasons. Yes, it is interesting to hear Elgar’s own tempo choices, but more importantly Harrison is an engaging soloist who plays with a depth and range that is amazing when you consider the age of the recording. She is fully attuned to the outpouring of grief and emotion inherent in the work, and this is a memorable performance.

Moving ahead to 1945 and recording technology had advanced quite a bit by the time legendary cellist Pablo Casals took up his bow to record the work with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Sir Adrian Boult, a recording available on Biddulph as well as other labels. On paper Casals and Boult would not be an ideal match, Casals the firebrand with a wild streak and Boult the stiff upper lip type. But Boult was often at his best with Elgar, and Casals brings passion and personality aplenty. The ensemble is not always tight, and Casals flubs a few notes. But it matters little when you have such expressive phrasing and such exquisite support from Boult. Casals’ tone was such that he could have played nearly anything and made it sound rich, but in this concerto, he adds an extra ounce of pathos, and he sounds natural and spontaneous. The Biddulph version is preferable to the Warner remastering in my opinion.

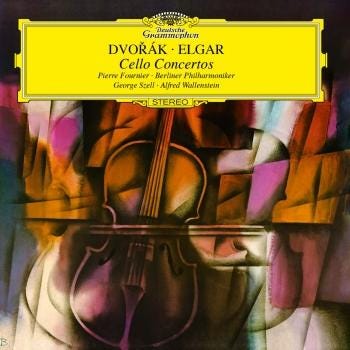

French cellist Pierre Fournier never played a boring note, and he had a distinctively full and aristocratic tone. His 1966 recording on Deutsche Grammophon with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra under conductor Alfred Wallenstein comes across significantly better than I remembered from previous hearings, and it deserves a recommendation. I should mention the cello is placed unnaturally forward in the picture, although this is not a big issue. Fournier’s warmth combined with his consistency of musical line guarantees Elgar’s structure is maintained while also highlighting the underlying emotional pulse. Fournier is never overly sentimental, and he never lingers unnecessarily, but his playing is completely disarming in its beauty.

The English cellist Robert Cohen was a young prodigy who made his debut on stage at the Royal Festival Hall at the age of 12. His first recording of Elgar’s Cello Concerto came when he was 19 with the London Philharmonic Orchestra under conductor Norman Del Mar for EMI (Warner). I did not expect a 19 year-old to be able to plumb the depths of this concerto, but Cohen’s understanding, virtuosity, and artistry turned out to be remarkably impressive by any measure. This is a reading of stature and expressivity, with the recorded sound having a nice balance putting us in the center of the audience. Cohen doesn’t miss a turn as far as the dramatic intensity required, and Del Mar and the LPO sound warm and generous. While Cohen’s instrument is not quite as full sounding as Maisky, Fournier, or Casals, its more piquant sound (similar to Yo-Yo Ma’s cello) actually lends the piece more spice. I will certainly be returning to this recording.

Jumping ahead to 1991 we have the recording from Soviet Israeli cellist Mischa Maisky on Deutsche Grammophon. He is supported by the late Italian conductor Giuseppe Sinopoli and the Philharmonia Orchestra. Maisky brings his typically extroverted personality to the concerto, but also his “heart on sleeve” approach which works well in the case of Elgar. I have always liked Maisky’s tone, and he is helped here by the atmospheric acoustic of Watford Town Hall, London. The Philharmonia shows a unity of vision with Sinopoli (something that was not always the case), and the tempos and dynamics are well judged. Maisky’s solo performance is deeply penetrating and certainly brings out the contrasting moods well. Recommended.

A recording that gives the du Pré account a real run for its money is the 2005 Orfeo recording by German cellist Daniel Müller-Schott with André Previn leading the Oslo Philharmonic. Müller-Schott is superb, technically impeccable with the ability to shade phrases in subtle ways and to inflect the music effectively. He has the emotional intensity required, but also is unfailingly refined and never sounds harsh. While the recording has a great deal of warmth and intimacy, the climaxes carry plenty of weight sonically. Of course, Previn was a considerable scholar of English music and was a marvelous Elgar conductor. His judgment of tempos and dynamics is spot on in my view, and he shows why he was always in demand to accompany concerto recordings. The Oslo Philharmonic may not be quite as full sounding as some others, but their playing is cohesive and absolutely first-rate.

Dutch cellist Pieter Wispelwey is one of my favorite cellists of recent decades, and regular readers will know he has appeared before in my surveys. His 2006 recording with the Dutch orchestra Radio Filharmonisch Orkest (Hilversum) under the direction of Jac van Steen is on the Channel Classics label and is an extremely perceptive and deeply felt performance. Wispelwey displays his masterful touch here again, as perhaps more than any other cellist on this list, he shows the ability to vary his tone both in terms of dynamics and rubato at will. His tone is always clean and clear, and while he tends toward the less emotive side, he also knows when to lean more heavily into the phrases. Wispelwey’s utter control is also evident, and so while you won’t hear the extrovert personality of a Casals here, his vision is one of continuous flow and momentum. Indeed, the first movement may be almost too controlled, but the cellist relaxes as things progress, and the final movement has tremendous feeling and sweep. The sound is warm, detailed, and natural.

Argentine cellist Sol Gabetta has recorded the Elgar concerto twice, but it is her first recording from 2010 on Sony that takes the recommendation. She is joined by Mario Venzago conducting the Danish National Symphony Orchestra. While Gabetta may benefit from some “splashy” promotion from Sony, she is the real deal as a performer. Here she finds an ideal balance between the intense yearning and melancholy in the score and an eloquence that even escapes du Pré on occasion. Gabetta is captured warmly, her cello is full sounding and resonant without a hint of coarseness, and she seems to have an intuitive sense of how this music should be played for maximum effect. At the same time, she has the virtuosic chops to play the faster passages and even infuses mystery into these passages. She is given strong support from the Danish orchestra under Venzago, although at times they are almost too strident. But it adds up to a satisfying and recommended recording. Gabetta’s later recording with Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic (2016) is similar in many ways and also well worth hearing (see honorable mention section).

Another legitimate contender versus du Pré is the 2012 recording by American cellist Alisa Weilerstein on Decca. She is joined by Daniel Barenboim and the Staatskapelle Berlin. First, kudos to the Decca engineers for top-shelf sound, among the finest sounding of all the recordings on this list. Weilerstein, similar to Gabetta, projects a warm and full sound from her cello which is certainly in the romantic vein. The opening by Weilerstein is bracing and almost jarring in its intensity. This is a signal that this will be a reading of passion and feeling, and indeed that is the case. Weilerstein followed this recording with a terrific recording of the Dvořák concerto, even if I’ve been marginally disappointed in her subsequent recordings. But never mind that, as on this occasion she is spectacular. Weilerstein manages the inward phrases in a heartfelt and subtle way, and the more extroverted moments are truly bursts of emotion and intensity. There is no doubt she has the measure of this score, and her tone throughout is sublime. Barenboim is unusually sensitive and deferential to the soloist, and his Berliners create a sumptuous and rich sound (much as they did on his award-winning recording of Elgar’s Symphony no. 1). This is a tremendous effort all around and enthusiastically recommended.

A wonderful surprise I found in this survey was the excellent 2016 recording by German cellist Marie-Elisabeth Hecker joined by the Antwerp Symphony Orchestra under Edo de Waart on the Alpha label. Hecker’s tone is somewhat leaner than Gabetta and Weilerstein, but she is so impressive in how she makes the cello sing. I should say her low notes are especially striking, and her sense of proportion and dynamics is right on. I love how Hecker adds some lilt to the melodies, and she genuinely sounds as though she is enjoying herself. Her natural lyricism is evident, and it is clear she has studied the score enough to infuse it with her own personality. In the softer, more intimate moments Hecker is touching in her subtlety and the almost woody sound of her cello adds to her individualism. De Waart is an ideal partner, leading the Antwerp orchestra to create a sound which complements Hecker perfectly. Their tone is also leaner than you will hear from Berlin or London, but the level of detail heard is stunning. This is an impressive recording all around and gets a full recommendation.

Finally on the recommended list is another 2016 recording, this time from German Canadian cellist Johannes Moser. He is joined by the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande led by Andrew Manze for this recording issued on the Pentatone label. This performance has a refreshing directness about it, and it never gets too bogged down in the melancholy. Oh, it is there to be sure, but Moser and Manze admirably maintain the flow throughout. The Pentatone engineering is exceptionally clear and warm, and the cello has an immediacy which is very appealing. Moser and Manze seem to locate the drama and the vibrancy in the score more so than the overt anguish, and this is a welcome approach. There is no excessive handwringing, but rather the team remains faithful to the score. Indeed, if you go back to Elgar’s own recording, we are reminded of how effective a more direct approach can be. In addition, we hear Moser’s rich and autumnal tone which carries all the emotion and fullness of the notes without Moser needing to indulge in his own eccentricities. Manze, once upon a time a period instrument specialist, shows that even the romantic strains of Elgar are in his wheelhouse. His leadership and the warmth of the OSR are remarkably clear and enjoyable. Heartily recommended.

Honorable Mention Recordings

Hallé / Navarra / Barbirolli (Warner 1957)

BBC / Du Pré / Barbirolli (Melodiya 1967)

LSO / Ma / Previn (Sony 1984)

RPO / Lloyd-Webber / Menuhin (Decca 1986)

LSO / Schmidt / Frühbeck de Burgos (LSO 1988)

LSO / Isserlis / Hickox (Warner 1989)

Philharmonia / Starker / Slatkin (Sony 1993)

CBSO / Mørk / Rattle (Warner 1999)

Hallé / Schiff / Elder (Hallé 2004)

RLPO / Wallfisch / Dickins (Nimbus 2006)

Philharmonia / Walton / Briger (Signum 2008)

BBC / Watkins / Davis (Chandos 2011)

BBC / Queyras / Belohlavek (HM 2012)

LPO / Qin / Yi (Long 2014)

BPO / Gabetta / Rattle (Sony 2016)

New Zealand / Hurtaud / Northey (Rubicon 2020)

See you next time when we cover #92 on the list, Richard Wagner’s opera Die Meistersinger. See you then!

_____________

Notes:

Kennedy, Michael (1972). Elgar: Cello Concerto & Sea Pictures. EMI Liner Notes.

Macdonald, Hugh (2016). Edward Elgar: Cello Concerto in E minor, Opus 85. Boston Symphony Orchestra Program Notes, Week 4, 2016-2017 Season. Pp. 39-45.

Moore, Jerrold N. (1984). Edward Elgar: a Creative Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315447-1.

Sternberg, Michael. The Symphony: A Listener's Guide, p. 155. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

Padfield, Will. What’s the history of Elgar’s Cello Concerto – the work with a disastrous premiere? December 12, 2024. Online at https://www.classicfm.com/composers/elgar/history-cello-concerto-disastrous-premiere/.

https://musicwebinternational.com/masterwork-idx/elgar-cello-concerto/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cello_Concerto_(Elgar)?scrlybrkr=40ad99ec

Thank you John for the exhaustive survey about this wonderful concerto. I have two listening suggestion for you: an historic performance by Erling Blöndal Bengtsson on Danacord (hard to find) and the recent Natalie Clein version with Royal Liverpool Symphony Orchestra and Vernon Handley on the baton. For my money both deserves a place in the list.