Building a Collection #90

Otello

By Giuseppe Verdi

____________

“A man like Verdi must write like Verdi.”

-Giuseppe Verdi

As we progress further up the list of the Top 250 Greatest Classical Works of All-Time, I hope you are becoming more familiar with some compositions that were previously unknown or little known to you. This is certainly true for me, and #90 on our list is a prime example. Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Otello in four acts is an opera I have known in the back of my mind was a truly great opera, but up until now I had only minimal knowledge of the music from the opera. Of course, Shakespeare’s Othello on which the opera is based was familiar to me, and I have seen the play. But it has been a joy to learn more about the opera, and I would like to share more about this discovery with you.

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)

Giuseppe Verdi was born in 1813 in Le Roncole, Italy and died in 1901 in Milan, Italy. Certainly one of the greatest opera composers in history, Verdi perfected Italian opera, taking the genre to new heights dramatically and musically. Considered among the greats in opera alongside Mozart, Wagner, and Puccini, Verdi lives on in the many performances of his greatest works including: Rigoletto, La Traviata, Il Trovatore, Aida, Otello, Falstaff, and his Messa da Requiem.

Verdi showed early musical talent on the piano, and by the age of 15 had already begun composing. After the Milan Conservatory turned him away, he studied privately with several well-known teachers. In 1839, after moving full-time to Milan, he composed his first opera Oberto. Oberto was a success, but his second effort, Un giorno di regno, was a failure. Worse yet, after tragically losing his two children in previous years, his wife died leaving Verdi alone and depressed. In the immediate years after his wife’s death, Verdi attempted to rebound with the operas Nabucco, I Lombardi, Macbeth, and Luisa Miller in a series of mostly successful productions.

In the period 1851 through 1853, Verdi wrote three of his most popular operas, Il Trovatore, La Traviata, and Rigoletto. Although Il Trovatore and Rigoletto were immediate successes, La Traviata was not well-received initially. After some revisions, it too became a great success. For a time Verdi was involved in politics, and this became evident in his next works, Simon Boccanegra and Un Ballo in Maschera. By now he was well established as one of the greatest composers of his time, and the public eagerly awaited his new works. In the 1860s, Verdi composed La forza del destino and Don Carlos, both premiered in St. Petersburg.

Verdi moved permanently to Genoa, Italy and composed Aida in 1870, which was a great success. But the composer gave up opera for a period of time thereafter, composing his String Quartet and Messa da Requiem in the 1870s. After a long opera gap, he turned out another opera in Otello in 1886 and then his final opera Falstaff in 1893. Falstaff, a bold and creative comic opera, became one of his greatest triumphs. In his final years, Verdi founded a hospital and a home for retired musicians. He retired to live at the Grand Hotel in Milan, composing his final work Quatro pezzi sacri (Four Sacred Pieces) published in 1897.

Otello

Verdi’s opera Otello is in four acts based on a libretto by Arrigo Boito based on Shakespeare’s play Othello. It was Verdi’s penultimate opera, with Falstaff still to come. The premiere was given at Teatro alla Scala in Milan in February 1887. Verdi had intended to retire from composing after the success of his opera Aida in 1871, and it would be another decade before Verdi even considered writing another opera.

Verdi’s publisher in Milan, Giulio Ricordi, refused to accept that Verdi was done writing operas because he believed Verdi still had much to create, and besides his operas were a cash cow for Ricordi. For many years, Verdi steadfastly refused to look at a libretto, or to even consider another project. But Ricordi was persistent, even communicating through Verdi’s wife Giuseppina to try to get the composer to reconsider. Ricordi knew that for there to be any chance of Verdi composing again, the libretto would have to captivate him and hold his interest. After more unsuccessful attempts at enticement, Verdi declared, "For what reason should I write? What would I succeed in doing?”.

In May 1879 Ricordi tried another approach, which was to ask Verdi to revise his 1843 opera Simon Boccanegra. Verdi refused, but Ricordi then suggested to him a collaboration with Boito (a fellow composer) on a libretto for Shakespeare’s Othello. Of course the story was well known to Verdi, and furthermore he had great admiration for Shakespeare’s works, always having the goal of adapting one of his plays for opera. Indeed, he had done so in 1847 with the opera Macbeth, which although initially successful was rather less so when the revised version was presented in Paris in 1865. But Verdi was intrigued by Othello, mostly because the story seemed to be straightforward and easily adapted.

Verdi agreed to work with Boito on the revision of Simon Boccanegra, and this helped solidify the working relationship between the two men, and it showed Verdi that Boito was well equipped to provide the full libretto for Othello (or what was to become Otello in Italian). At a private dinner with Ricordi in May of 1879, a subtle suggestion was made to Verdi about using Othello as the subject of a new opera and the possibility of working with Boito on the libretto. Ricordi recounted the conversation:

“The idea of a new opera arose during a dinner among friends, when I turned the conversation, by chance, on Shakespeare and on Boito. At the mention of Othello I saw Verdi fix his eyes on me, with suspicion, but with interest. He had certainly understood; he had certainly reacted. I believed the time was ripe.”

While Verdi remained noncommittal, he indicated that he was open to receiving whatever Boito worked on and to review it. Just a few months later Boito sent Verdi what he had created so far. Giusseppina secretly told Ricordi that "Between ourselves, what Boito has so far written of the African seems to please him, and is very well done”. Between 1881 and 1884, little was done on the project. In fact, Ricordi was impatient and for three Christmases in a row sent the Verdis a large cake with a chocolate statue of Othello on top as further encouragement. While Verdi still dragged his feet, in 1884 he began to slowly work on something based on what Boito had sent him. Over the course of about a year and a half, Verdi had spent three considerable chunks of time working on the music for the libretto, and was making good progress.

In his correspondence with Verdi, Boito continued to encourage Verdi to compose and indicated that it was his view that Verdi was destined to complete Otello because of his affinity for Shakespeare. Verdi wrote to Boito: "It seems impossible, but it's true all the same! I'm busy, writing!! ... without purpose, without worries, without thinking of what will happen next...". When Verdi finished the fourth act in October of 1885, he wrote to Boito,"I have finished the fourth act, and I breathe again". Yet the additional scoring and finalizing the text took many more months, but finally in November of 1886 Verdi was able to send the message: "DEAR BOITO, It is finished! All honour to us! (and to Him!!). Farewell. G. VERDI".

Rumors were flying in Italy about Verdi writing another opera, and there was rampant speculation. While the location, the Teatro all Scala in Milan, had been chosen and the conductor and principal singers had been tapped as well, the opera was shrouded in secrecy until the premiere. Truth be told, Verdi was not completely confident about the opera or the singers. But he need not have worried, for the premiere on February 5, 1887 proved to be a resounding success, so much so that Verdi was called back for 20 curtain calls! The opera was soon staged throughout Europe and the United States. As we know today the opera is frequently performed throughout the world and is considered part of the standard opera repertoire.

The roles in the opera are as follows:

Role

Otello, a Moorish general - tenor

Desdemona, his wife - soprano

Iago, Otello's ensign - baritone

Emilia, wife of Iago and maid of Desdemona - mezzo-soprano

Cassio, Otello's captain - tenor

Roderigo, a gentleman of Venice - tenor

Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic - bass

Montano, former Governor of Cyprus - bass

A herald - bass

Chorus: Venetian soldiers and sailors; and Cypriot townsfolk and children

For much of the history of Otello it has been common practice to blacken the face of the title role because he is a Moor from Africa. However, the Metropolitan Opera stopped this practice in 2015. Some critics argue that in the case of Otello, the dark face is merely accurate costuming and not a true example of “blackface”. Others have used the controversy as a reason to push for more diverse casting and more opportunities for people of color in opera.

The following is a condensed synopsis of Otello from the Metropolitan Opera online:

ACT I

Cyprus, late 19th century. During a violent storm, the people of Cyprus await the return of their governor and general of the Venetian fleet, the Moor Otello. He has been fighting the Muslim Turks and guides his victorious navy to safe harbor. In his absence, the young Venetian Roderigo has arrived in Cyprus and fallen in love with Otello’s new wife, Desdemona. Otello’s ensign Iago, who secretly hates the governor for promoting the officer Cassio over him, promises Roderigo to help win her. While the citizens celebrate their governor’s return, Iago launches his plan to ruin Otello. Knowing that Cassio gets drunk easily, Iago proposes a toast. Cassio declines to drink, but abandons his scruples when Iago salutes Desdemona, who is a favorite of the people. Iago then goads Roderigo into provoking a fight with Cassio, who is now fully drunk. Montano, the former governor, tries to separate the two, and Cassio attacks him as well. Otello appears to restore order, furious about his soldiers’ behavior. When he realizes that Desdemona has also been disturbed by the commotion, he takes away Cassio’s recent promotion and dismisses everyone. Otello and Desdemona reaffirm their love.

ACT II

Iago advises Cassio to present his case to Desdemona, arguing that her influence on Otello will secure his rehabilitation. Alone, Iago reveals his bleak, nihilistic view of humankind. He makes dismissive remarks about Desdemona’s fidelity to Otello, whose jealousy is easily aroused. Otello’s suspicions are raised when Desdemona appears and appeals to him on Cassio’s behalf. Otello evasively complains of a headache, and Desdemona offers him a handkerchief, which he tosses to the ground. Emilia, Iago’s wife and Desdemona’s maidservant, retrieves it, and Iago seizes the handkerchief from her. Left alone with Otello, Iago fans the flames of the governor’s suspicions by inventing a story of how Cassio had spoken of Desdemona in his sleep, and how he saw her handkerchief in Cassio’s hand. Seething with jealousy, Otello is now convinced that his wife is unfaithful. The two men join in an oath to punish Cassio and Desdemona.

ACT III

Iago’s plot continues to unfold as he tells Otello that he will have further proof of his wife and Cassio’s betrayal. When, moments later, Desdemona approaches Otello and once again pleads for Cassio, Otello again feigns a headache and insists on seeing the missing handkerchief, which he had once given her as a gift. When she cannot produce it, he insults her as a whore. Alone, he gives in to his desperation and self-pity. Iago returns with Cassio, and Otello hides to eavesdrop on their conversation, which Iago cleverly leads in such a way that Otello is convinced they are discussing Cassio’s affair with Desdemona. Cassio mentions an unknown admirer’s gift and produces the telltale handkerchief—in fact planted by Iago in his room. Otello is shattered and vows that he will kill his wife. Iago promises to have Roderigo deal with Cassio.

A delegation from Venice arrives to recall Otello home and to appoint Cassio as the new governor of Cyprus. At this news, Otello loses control and explodes in a rage, hurling insults at Desdemona in front of the assembled crowd. He orders everyone away and finally collapses in a seizure. As the Cypriots are heard from outside praising Otello as the “Lion of Venice,” Iago gloats over him, “Behold the Lion!”

ACT IV

Emilia helps the distraught Desdemona prepare for bed. She has just finished saying her evening prayers when Otello enters and wakes her with a kiss to tell her he is about to kill her. Paralyzed with fear, Desdemona again protests her innocence. Otello coldly strangles her. Emilia runs in with news that Cassio has killed Roderigo. Iago’s plot is finally revealed and Otello realizes what he has done. Reflecting on his past glory he pulls out a dagger and stabs himself, dying with a final kiss for his wife.

While of course Otello is the main character of the opera that bears his name, Iago is arguably just as important, if not more so, to the drama and the success of any performance. If you are familiar with the story, or have seen the play, you understand the reason. I would argue that the tenor singing Otello and the baritone singing Iago are the most important roles in the opera, although Desdemona has a few terrifically demanding arias and her role may be sung and acted in different, but equally effective ways. Of course, the conductor is also an essential component to any successful performance or recording.

In summary, the importance of Verdi’s opera Otello cannot be overstated because it showed that even after taking a decade off from composing, he still had the gift. And although Rossini had previously composed an Otello as well, there can be little doubt about the greatness of Verdi’s work and how well it represents Shakespeare’s unspeakable tragedy.

Recommended Recordings

The three primary roles of Otello (tenor), Desdemona (soprano), and Iago (baritone) are extremely demanding and require a lot of skill both vocally and dramatically. The tenor role of Otello is often considered to be the highest pinnacle of operatic art to be surmounted in terms of sheer range. Iago’s baritone voice must be intelligently crafted, weighty, infused with personality and well acted. Desdemona must convey not only beauty and emotion, but must also show firmness of voice in the ensemble numbers and in her two arias, the “Willow Song” and the “Ave Maria”. Down through the performance history of Otello, many of the greats of opera have taken on these roles. The most celebrated and effective Otellos on stage and on record have included Ramón Vinay, Mario del Monaco, Jon Vickers, and Plácido Domingo. Some of the most famous Iagos include Tito Gobbi, Leonard Warren, Lawrence Tibbett, and Giuseppe Valdengo. For Desdemona there have been many famous performances, but most notably those by Elisabeth Rethberg, Renata Tebaldi, Mirella Freni, and Margaret Price. Having said that, you dear listener must decide for yourself what kind of voice quality and dramatic sensibility you believe fits the role and the story best. We can disagree of course on matters of taste.

Many of the greatest conductors have taken the podium for Otello productions as well, but those that have been most successful in my view include Arturo Toscanini, Alberto Erede,Tullio Serafin, Alain Lombard, and James Levine. Toscanini played cello under Verdi for the premiere in 1887, Votto was later Toscanini’s assistant at La Scala, and Erede attended the Verdi Conservatory in Milan. When you look at my reviews below, you will notice that they skew significantly toward recordings from the 1940s through the 1970s, generally acknowledged as the golden era of opera recordings. There are a few outside that timeframe, but not too many. In the case of Otello, my bias is strongly for the older recordings, and I am afraid that in general opera performances and recordings from more recent decades are not in the same league. But I am open to being persuaded otherwise.

Two further notes about the recommendations below. I am only reviewing complete and unabridged recordings, and I will only comment on the three principal soloist voices in each recommendation. That is not to say the quality of the supporting cast are not important, but they are of lesser importance in my view.

The earliest recording that deserves a recommendation is the 1947 RCA recording by Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus taken from live broadcasts in Studio 8-H. One of the first great Otellos on record, the Chilean tenor Ramón Vinay, is featured here along with a terrific performance by baritone Giuseppe Valdengo as Iago, and with soprano Herva Nelli as Desdemona. Toscanini leads a confident and extroverted performance full of vibrancy and energy. Vinay has a particularly strong and forceful voice and uses it well in that regard. For me, he also characterizes the inner conflict of the Otello in a way that feels authentic. The Iago of Valdengo is perhaps my favorite on record, and he sings with a vocal acting component that well represents the morally compromised character. Nelli is not my favorite Desdemona either vocally or dramatically, and Toscanini esteemed her voice to a fault in my opinion in using her for so many recordings, but she is perfectly fine and sings consistently well. The sound is rather dry, but very good for its age and far better than many other live recordings of the time.

Italian conductor Alberto Erede was vastly underrated as a conductor, especially of Italian opera. His 1954 studio recording on Decca is also an underrated version of Otello, but for me it checks all the boxes. Erede directs the Orchestra e Coro dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome, and soloists are Mario Del Monaco as Otello, Renata Tebaldi as Desdemona, and Aldo Protti as Iago. It was around this time that Del Monaco was beginning to be recognized as the next great Otello. His singing is not only heroic, but it feels his voice is just right for the role. While it is true the sound has some roughness to it, and Del Monaco in particular has some unsteadiness, it feels part and parcel of the evolution of the character he is playing. Tebaldi is captured early enough that her voice still has the soaring and creamy high notes. Protti is not at the same level, and he is not as effective as some others such as Gobbi or Tibbett, but his voice is quite good, and his acting is on point. Similar to Toscanini, Erede leads a committed and energetic performance in good sound. Recommended.

The name of conductor Fausto Cleva was completely unknown to me, but I have now been educated. His live 1958 recording with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus (issued on the Myto label, but also on Pristine), is a model of refinement and intensity. The sound quality is surprisingly good and while it is apparently in mono, it is every bit as good as many stereo recordings. This is perhaps Mario Del Monaco’s finest Otello on record, or certainly among the best, and his voice is nothing less than thrilling. Leonard Warren’s Iago is excellent, and although I prefer Gobbi’s voice, Warren’s performance is inspired and satisfying despite his rather wide vibrato. Victoria de los Angeles is of course one of the great sopranos of the century, and she shows a good understanding of the role by emphasizing the emotional vulnerability of Desdemona. All in all, this is a solid recommendation.

It was just five years later that we find Erede again, this time in a live mono recording taken from a performance in Tokyo in 1959, the recording was issued by Andromeda and other labels. The orchestra is the NHK Symphony Orchestra, the Tokyo Broadcasting Chorus, the NHK Italian Opera Chorus, the Fujiwara Opera Chorus, and the Tokyo Boys’ Choir. This is a revelation as well, and the sound is remarkably good for a live recording of this vintage. Yes, there are some odd stage and audience noises, but that hardly gets in the way of what is a gripping live performance. We hear Del Monaco again in even better voice than five years earlier and equally dramatic. Desdemona is Gabriella Tucci, a name I was not familiar with, but she is nothing short of outstanding, with a lovely and effortless voice. What also raises this to the top tier is the Iago of Tito Gobbi, one of my favorite baritone voices ever. Not so different from his famous characterization of Scarpia in Tosca, Gobbi brings confidence and fearlessness to his performance. It is a delectable account, and he even pulls off all the high notes asked of him. There are some minor slips occasionally, as well as some roughness in the chorus, but in terms of bringing off the most dramatic and tragic aspects of the story, this cannot be beat.

Just a year later in 1960 we encounter a studio production led by Italian conductor Tullio Serafin on RCA Living Stereo (Sony). Serafin leads the Orchestra and Chorus of the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma with soloists Jon Vickers as Otello, Leonie Rysanek as Desdemona, and Tito Gobbi as Iago. While none of the three principals have the most beautiful voice, this is an example of a recording where the white-hot intensity and sheer passion carry the day. Gobbi is again outstanding as Iago, even though his voice is beginning to show some marginal decline. Vickers voice has an edge to it, but his Otello is distinguished and original in its dramatic intensity. Rysanek seems perhaps a bit miscast to me, her palette is too heavy and mature sounding, but she has the measure of the emotional turmoil of the role. Serafin’s conducting is refined and fully idiomatic, if less urgent and dramatic than Toscanini and Erede. Still, this is a very fine set for Vickers and Gobbi and for the excellent sound for its vintage.

There can be little doubt that Plácido Domingo is one of the finest Otello interpreters on record, and like Del Monaco, he performed it hundreds of times on stage. Domingo recorded the role three times, and many critics and listeners like his final recording with Chung on DG. But I prefer his first recording from 1978 on RCA conducted by James Levine joined by the National Philharmonic Orchestra (London) and the Ambrosian Opera Chorus. While Domingo is not as ideal vocally for the role as Del Monaco and Vinay, there is no question he is an excellent dramatic performer. For me his voice doesn’t carry enough weight, and at times his tone has a tendency to become nasally and thin in the higher register. But the power of his younger voice here helps him enormously, and he brings out the emotional aspects so well. Moreover, Levine’s conducting is electrifying and superb throughout and the sound of the studio recording is outstanding. Sherrill Milnes is in his prime here, and we get to hear his rich, full, and satisfying voice. If he doesn’t quite get inside the character and doesn’t have the edge or growl of Gobbi or Tibbett, his singing is still very enjoyable. By this time Renata Scotto’s voice had declined some from her prime, and there was a noticeable slight break in her high notes. Nevertheless, she is completely convincing emotionally and has a wonderful lower register intact. She also can sing the softer parts in a moving and heartbreaking way. This recording might not be the top choice, but it is satisfying and recommended.

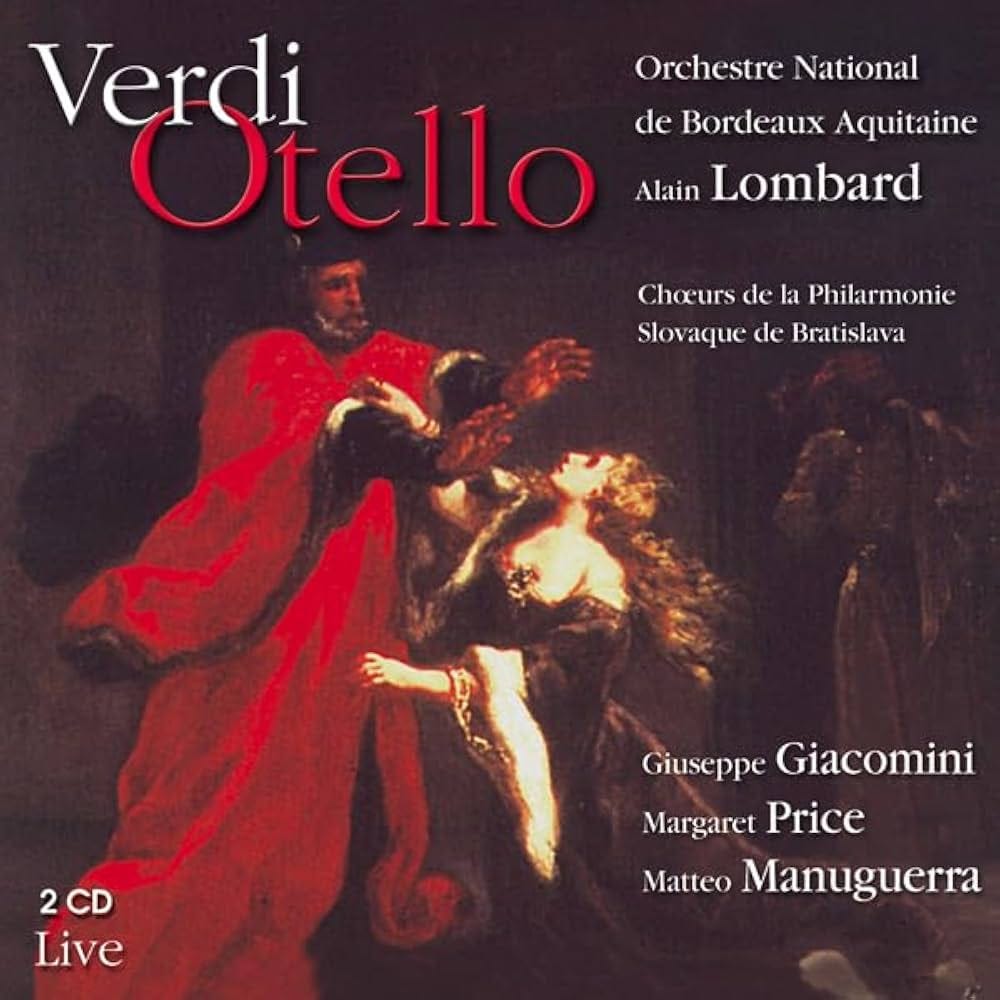

In looking at the versions of Otello available on streaming services, I noticed one conducted by French conductor Alain Lombard. I passed it over initially but then went back and began to listen to it. As it turns out, this recording turned out to be a very pleasant surprise in nearly every way and can be confidently recommended. The recording is taken from live performances in 1991 with the Orchestre National Bordeaux Aquitaine, the Slovak Philharmonic Choir, and Les Petits Chanteurs de Bordeaux. It was issued on the Forlane label, but as I mentioned it is available to stream. Considering this is a live recording, the sound is excellent. Lombard’s approach has more in common with Serafin than Toscanini, but the orchestra, chorus, and soloists all bring exceptional effort and artistry to the performance. I should first point out the terrific Desdemona of Margaret Price, one of the finest on record. Her top notes float wonderfully, and her tone has weight and yet vulnerability. Giuseppe Giacomini as Otello is fully up to the task, carrying the part with a voice that possesses weight and secure top notes. Finally, Matteo Manuguerra was unknown to me, but his Iago is positively menacing and intimidating, and his acting is top notch. Put it all together and you have a highly recommended recording.

Honorable Mention Recordings

Metropolitan Opera / Panizza (Sony 1938)

Metropolitan Opera / Busch (Preiser 1948)

Vienna Philharmonic / Karajan (DG 1961)

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden / Solti (ROH 1992 DVD)

Opera Bastille / Chung (DG 1993)

Thanks to everyone for your readership, and I appreciate your support. Please join me next time for #91 on the list, Edward Elgar’s wonderful Cello Concerto. See you then.

________________

Notes:

"An Otello Without Blackface Highlights an Enduring Tradition in Opera". The New York Times. 20 September 2015.

Budden, Julian (1992). The Operas of Verdi. Vol 3: From Don Carlos to Falstaff (2nd ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-30740-8.

"Met's Otello casting begs the question: Is whitewash better than blackface?". The Globe and Mail. 7 August 2015.

Parker, Roger (1998). "Otello". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-522186-2.

Moore, Ralph. Verdi’s Otello - A partial discographical survey. https://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2019/Mar/Verdi_Otello_survey.pdf.

Walker, Frank (1982) [1962]. The Man Verdi. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-87132-0.

https://www.azquotes.com/quote/1048081

https://www.metopera.org/user-information/synopses-archive/otello/

![Otello : Erede / NHK Sympnony Orchestra, Del Monaco, Gobbi, etc (1959 Stereo Tokyo Live)(2CD) : Verdi (1813-1901) | HMV&BOOKS online : Online Shopping & Information Site - ANDRCD5143 [English Site] Otello : Erede / NHK Sympnony Orchestra, Del Monaco, Gobbi, etc (1959 Stereo Tokyo Live)(2CD) : Verdi (1813-1901) | HMV&BOOKS online : Online Shopping & Information Site - ANDRCD5143 [English Site]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!egxw!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb5c95cbb-0b93-46df-b88c-f072873775d8_400x400.jpeg)

Opera was the precursor of the musical and therefore jazz