Building a Collection #88

Adagio for Strings (from String Quartet, Op. 11)

By Samuel Barber

____________

“…In fact, it is said that I have no style at all, but that doesn't matter. I just go on doing, as they say, my thing. I believe this takes a certain courage.”

-Samuel Barber

At #88 on the list of the Top 250 Classical Works is American composer Samuel Barber’s iconic Adagio for Strings. Next to Pachelbel’s Canon, the Adagio for Strings is one of the shorter works on our survey, as performances of it average about 9 minutes. It is also a work that has been embedded in the public consciousness due to the emotional catharsis it contains in the score. It is one of the most haunting and memorable works ever composed.

Samuel Barber (1910 -1981)

Samuel Barber was an American composer, pianist, conductor, and music educator. He is regarded as one of the greatest American composers of the 20th century. Even though Barber came of age in a time when modernism was taking over classical music, he primarily avoided modernism and instead continued with the more traditional tonal and emotionally expressive musical language of the late 19th century.

Barber was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania into a cultured and relatively prominent family. His father was a physician, and his mother was a pianist. His aunt, Louise Homer, was a contralto opera singer who sang regularly at the Metropolitan Opera and his uncle Sidney Homer was a composer of some renown in the area of American art songs. It is believed that Barber gained his interest in song and the human voice through his aunt and uncle, and his uncle Sidney became Barber’s musical mentor for some 25 years. There can be little doubt that his uncle influenced Barber’s compositional style significantly.

The young Barber was a prodigy at the piano, studying from the age of six, and composing his first piano piece at the age of seven. While his parents held out hope their son would be a typical boy, outgoing and athletic, Samuel was clearly not typical and was not interested in sports. At the age of nine, he wrote to his mother:

Dear Mother: I have written this to tell you my worrying secret. Now don't cry when you read it because it is neither yours nor my fault. I suppose I will have to tell it now without any nonsense. To begin with I was not meant to be an athlete. I was meant to be a composer, and will be I'm sure. I'll ask you one more thing.—Don't ask me to try to forget this unpleasant thing and go play football.—Please—Sometimes I've been worrying about this so much that it makes me mad (not very).

By the age of 10, Barber had written an operetta called The Rose Tree, and at the age of 12 he accepted a job playing the organ at a local church. At 14, Barber entered the youth artist program at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where he would spend ten years honing his gifts in piano, composition, conducting, and voice. He studied under several well-known musicians, most notably Fritz Reiner for conducting. In 1928, he met Italian classmate and composer Gian Carlo Menotti, who would become his life partner as well as musical colleague.

Barber composed rather prolifically as a young man, and those works could be described as tonal and lyrical with moderate use of dissonance and chromaticism. His first big success was The School for Scandal Overture, for which he was awarded the Bearns Prize from Columbia University, written when he was just 21. During his time at Curtis, Barber also used the summer months to travel extensively in Europe, including visits to France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, and Austria. Time spent in Paris, Vienna, and Italy (with Menotti) proved quite influential to Barber’s style. While he had been composing, Barber still wanted to become a baritone vocalist and thus spent a lot of time on that craft while in Europe (indeed Barber would eventually have a short-lived career singing with the NBC Music Guild). At the same time, Barber was taking conducting lessons as well. Through the benefit of being awarded a Pulitzer scholarship in 1935, as well as winning the Rome Prize, Barber was able to study at the American Academy in Rome from 1935 to 1937. Some years later in 1946, he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship which gave him the ability to study conducting privately with George Szell. Throughout those years, Barber maintained his strong interest in the human voice, and fully two-thirds of his compositional output would eventually be in the form of song.

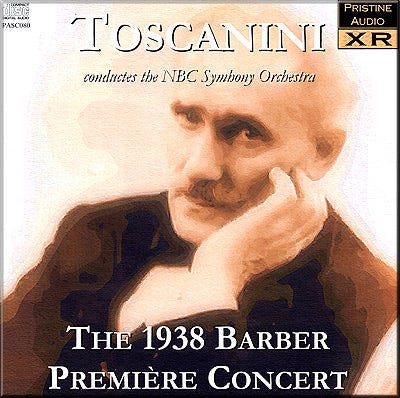

While in Rome, Barber composed his first major orchestral work, his Symphony in One Movement, which would eventually be played in New York and Cleveland, as well as being the first orchestral composition by an American to be played at the Salzburg Festival in 1937. In 1938, Barber’s Adagio for Strings was premiered by the NBC Symphony Orchestra under Arturo Toscanini after being adapted and arranged for orchestra from his String Quartet Op. 11. Toscanini conducted relatively few American works, but after the first rehearsal for the Adagio, he commented on the work’s simplicity and beauty. Toscanini would also stay true to the composer’s pacing for the work, which Barber maintained should be between seven and eight minutes. Over the years, other conductors would slow the piece down, maintaining that it works better at a slower tempo, where today the average playing time is closer to nine minutes.

Around 1940 the beginning of the second part of Barber’s career saw him include more modern styles and techniques into his music. Barber became more influenced by composers such as Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and Bartók, as well as American jazz. Barber served in the Army Air Corps during the war, and while serving was commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Serge Koussevitzky, those works included his Cello Concerto and what was his Symphony no. 2. Barber revised the symphony later, and it was published by Schirmer in 1950. Barber even recorded the score with the NSO of London in 1951, but it is believed Barber inexplicably destroyed the score years later. Pieces of the score were later found and reconstructed, but it is unclear whether that resulting score is what Barber intended.

Barber and Menotti purchased a home north of New York City in the suburbs in 1943, and it was there that Barber was most productive as a composer from that point until the end of his life. He composed his best known works there including the ballet Medea, his work Knoxville: Summer of 1915 for soprano and orchestra, and his Piano Sonata, which was premiered to great acclaim by Vladimir Horowitz, and which has become one of his most beloved works. In 1953, Barber met soprano Leontyne Price and he was quite struck by the quality of her voice. Subsequently, Barber engaged Price to premiere several of his works including the song cycle Hermit Songs and the cantata Songs of Kierkegaard with the BSO.

Barber won the Pulitzer Prize in 1958 for his opera Vanessa, which premiered at the Metropolitan Opera with a star-studded cast including Nicolai Gedda, Eleanor Steber, Rosalind Elias, Regina Resnik, and Giorgio Tozzi. Later Vanessa was produced at the Salzburg Festival, becoming the first American opera to be played there. The opening of Lincoln Center in New York produced the commission for Barber’s Piano Concerto, with pianist John Browning as the dedicatee. It was premiered at Philharmonic Hall in 1962 by the New York Philharmonic with Browning as soloist, and was well received. However, another commission for Lincoln Center, his final opera Antony and Cleopatra, was poorly received when it premiered in 1966. It is thought this rejection deeply affected Barber, and he went into a depression and his alcoholism emerged. Barber spent more time in isolation, and Menotti urged them to end their romantic relationship, which happened in 1970. The house in New York was sold, but Barber and Menotti remained on friendly terms.

Barber continued composing during his later years, and his most notable compositions from that period are his cantata The Lovers from 1971, which received acclaim at its premiere with the Philadelphia Orchestra. His final major work was his Third Essay for Orchestra from 1978.

Barber passed away in 1981 at the age of 70 after a long battle with cancer.

Adagio for Strings

The Adagio for Strings was originally the second movement of Barber’s String Quartet, but he wrote the orchestral arrangement later in 1936, the same year the quartet was completed. Arturo Toscanini gave the premiere of the orchestrated version on November 5, 1938 with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, which was a live broadcast from NBC Studio 8H. The piece has unofficially been accepted in the United States as music that is often played during periods of national mourning. It has also appeared in TV and movie soundtracks.

Interestingly, when Barber sent the score to Toscanini in 1938, Toscanini sent it back to him without any comment which annoyed Barber. But Toscanini sent word through Barber’s partner Menotti that indeed he would be playing the piece and the only reason he sent it back was because he had already memorized it. Toscanini didn’t look at the score again until the day before the premiere. While it was warmly received by some critics, others disagreed and felt it was overrated.

According to music theorist Matthew BaileyShea, the Adagio "features a deliberately archaic sound, with Renaissance-like polyphony and simple tertian harmonies" underlying a "chant-like melody". The work is in "the key of B♭ minor (with some modal inflections)". The Adagio is an example of a form which builds on a melody that first ascends and then descends in stepwise fashion. Meanwhile, Barber varies the tempo slightly throughout which gives it the pulse it has.

Music critic Olin Downes wrote that the piece is very simple at climaxes but reasoned that the simple chords create significance for the piece. Downes said: "That is because we have here honest music, by an honest musician, not striving for pretentious effect…”

The key to the music’s emotional impact, according to music commentator and composer Rob Kapilow, "is that beneath all this emotion, it is one of the most clearly calculated and strongly simple and direct constructions of any piece.” Kapilow says the melody, which sounds so emotional, is "completely mathematical…You have a sequence of three notes up, three notes up again, then you do it up a step. Then you do it again. And then ... just, stop. The simplest pattern," he says. “A whole second wing of copying the pattern starts in the violas. Gradually, the slow repetitions acquire more expression and emotion.” In explaining why the piece is often used for mourning or funereal processions, Kapilow says, “it starts from incredible sadness, builds to an incredible climax of intensity, and then finally reaches a kind of serene acceptance, which is completely appropriate for those occasions.” What's so powerful, Kapilow says, “is the inevitability of the emotional cycle of the piece. The simplicity of it: You hear it once, it's copied again, it comes back, it reaches a climax, then gets reduced to four notes…the simplicity of the logic, is to make you feel the universality of the journey: from the simple note to the high emotional wailing to release and to final acceptance, but never in the place you thought it was going to lead you to…the slowness is at the core of the piece, because acceptance is not a rapid process."

The Adagio for Strings may just be the most recognizable piece of American orchestral music ever written. It is Barber’s most famous work, and has become part of the standard repertoire. Despite its mournful tone and dissonant nature, the Dutch DJ Tiësto took the music as the basis for one of his most well-known dance tracks Adagio for Strings, which became a popular dance anthem. In 2004, however, BBC listeners named Adagio for Strings the saddest classical work ever composed. Many of you may have come to know Adagio for Strings the same way I did, as part of the soundtrack for the 1986 Oliver Stone movie Platoon, which depicted the horrors of the Vietnam War. It is an unforgettable part of the film, as it accompanies Charlie Sheen’s voice commentary at the end, and it perfectly captures how painful the Vietnam era was for people on all sides of the conflict.

Other notable times Adagio for Strings has been used include the following events, among others:

Broadcast over radio at the announcement of Franklin D. Roosevelt's death in 1945.

Played at the funeral of Albert Einstein in 1955.

Performed by the National Symphony Orchestra in a national radio broadcast following the funeral of assassinated President John F. Kennedy in 1963. The piece was one of Kennedy's favorites.

Conducted by Leonard Bernstein at four consecutive New York Philharmonic concerts in memory of Samuel Barber shortly after Barber's death in 1981.

Performed at Last Night of the Proms in 2001 at the Royal Albert Hall, London to honor the victims of the September 11 attacks.

Played in Trafalgar Square, on January 9, 2015, by an ensemble of 150 string players led by Thomas Gould of the Aurora Orchestra following the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo.

Played in Central Park in New York City on June 15, 2016, for the victims of the Orlando nightclub shooting.

Played at the televised memorial in Manchester, England on May 23, 2017, for the victims of the Manchester Arena bombing.

Played at the digital European Concert in the Berliner Philharmonie by the Berlin Philharmonic under Kirill Petrenko on May 1, 2020, for Covid-19 victims.

For his part, Barber didn’t love that he became almost exclusively associated with the Adagio for Strings, commenting in an interview in 1978 that he wished his other pieces would be played more often. But you cannot deny how achingly beautiful the piece is, and how meaningful it is to people of all backgrounds.

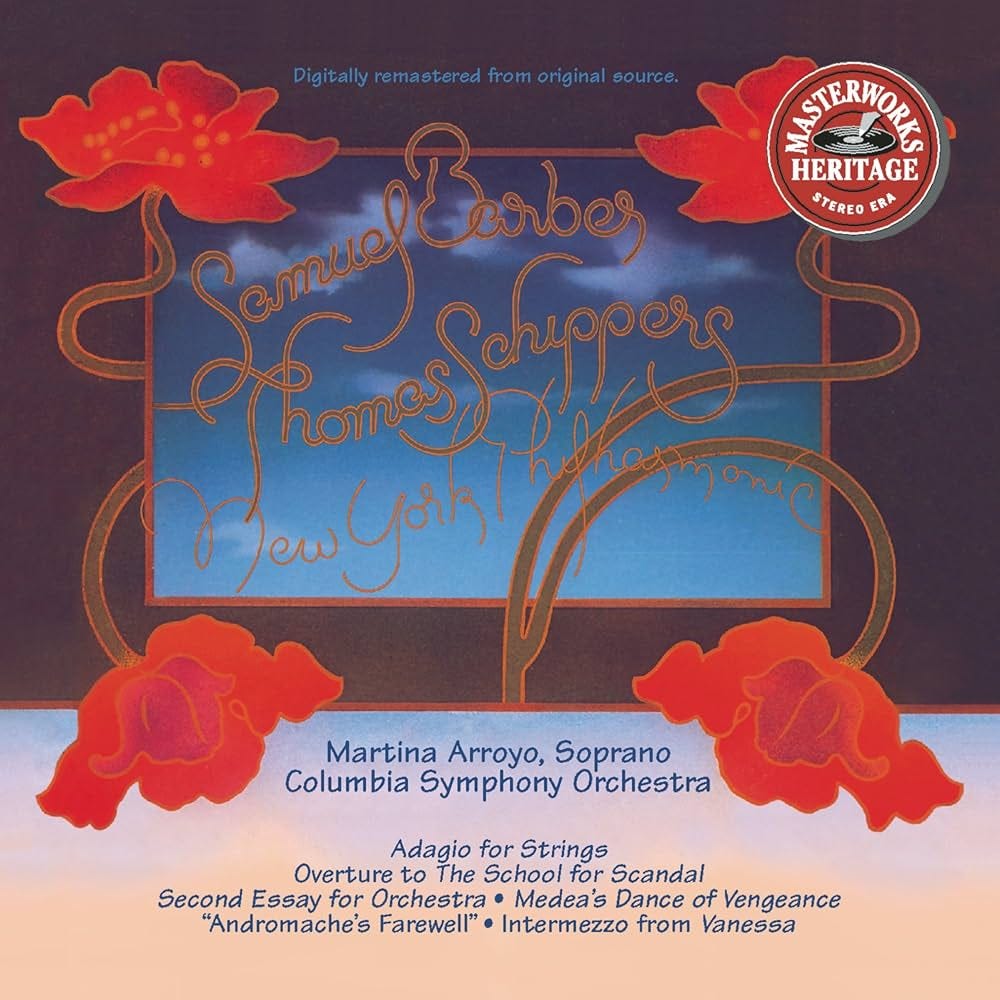

The Essential Recording

Choosing an essential recording for such a short piece is somewhat difficult, but in this case, there is one that stands out and has been front and center for decades now. The 1965 recording of Adagio for Strings by the American conductor Thomas Schippers and the New York Philharmonic on the Columbia (Sony) label has stood the test of time as the one recording that truly captures all aspects of this score in a balanced reading. It doesn’t move too fast, robbing the score of emotion and passion; nor does it try to wring every ounce of feeling out of it at the expense of the structure.

Schippers was a bright light in the music world, particularly in opera, where he was extremely well regarded. After spending time as Leonard Bernstein’s protégé, Schippers went on to conduct many operas at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, as well as guest conducting the New York Philharmonic and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Eventually he would land his own directorship with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. But his life was tragically cut short by lung cancer in 1977 at the age of 47.

With any performance of the Adagio, the tempo and total playing time are important, as they indicate how much the conductor will “milk” long-breathed phrases, and rests, for emotive effect. Performances between 7 and 8 minutes were prescribed by Barber, but in reality that tends to be on the faster end for the music and perhaps drains some of the passion from the score. On the other hand, performances which wallow in the emotion too much lose some momentum.

With Schippers, timing is at 9:03, so he lets the phrases breathe plenty and also allows us to hear the underlying bass line quite well. The balance is near ideal, as all the voices of the orchestra can be heard equally well, something Schippers’ time in the opera pit would have suggested. Each time the main theme returns, Schippers carefully builds the dynamics and controls the tempo perfectly. The cellos and violas are especially poignant, almost more than the violins, a credit to Schippers’ big picture of the score. Nothing is rushed, but neither does he pull out the big schmaltz a la Bernstein (nothing against schmaltz). The echoing phrases at 5:09 are masterfully done. Even in the build up to the main climax, we continue to hear each and every line of the orchestra, where with some recordings the top strings overpower the bottom. Finding the “correct” tempo and pulse in this music is somewhat open to interpretation, but for me Schippers nails it perfectly…not only with the consistency of his pace, but also in terms of when to really push the volume higher.

There are other excellent recordings of Barber’s Adagio, but in reality how many do you need with a piece this short? If you stopped now with the Schippers recording, you would do very well indeed. It is a recording for the ages in my opinion.

Recommended Recordings

The very first recording of Adagio for Strings was made by Arturo Toscanini and his fine NBC Symphony Orchestra, recorded live in 1938 in Studio 8H at Rockefeller Center in New York, and broadcast on the radio. This was also the premiere of the orchestrated version of the work. Toscanini, in his rather extrovert and objective way, plays the piece quicker than we are used to now (timing at 7:13), and he tends to underplay the pathos in his typically unsentimental way. Nevertheless, I recommend this recording not just for historical reasons, but also because I think it is closer to the composer’s intentions in terms of pacing and also because it is extremely well played. Despite the sonic limitations which are real, the sound is decent enough to allow us to hear everything well (and actually on the Pristine remastering sounds even better). Don’t get me wrong, Toscanini doesn’t miss the passion, and the climax is as wrenching as they come. But there is no wallowing in it.

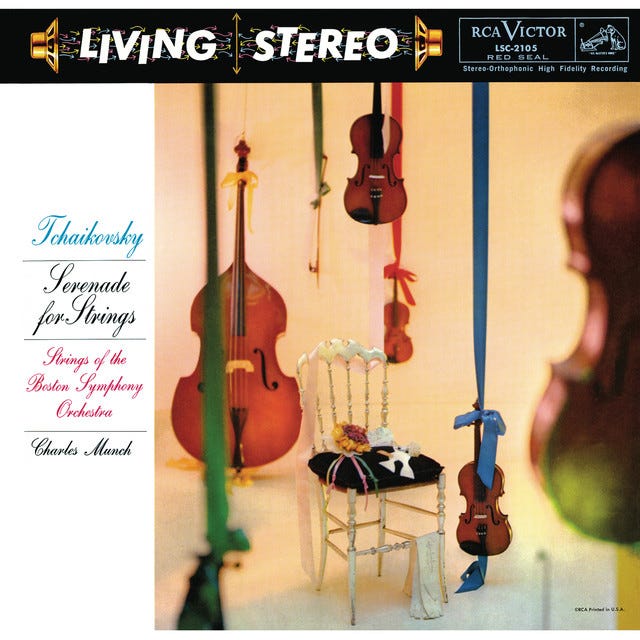

Fast forward to 1957, and we have the very fine account by Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra on RCA Living Stereo. I compared this recording back-to-back with Eugene Ormandy’s Philadelphia recording from the same year, and Munch has better sound and evokes more raw emotion, although he is on the quicker side at 7:44. I admit to some bias, as I love Munch’s recordings from the Living Stereo series, and because of the acoustics of Symphony Hall in Boston. There are a lot of parallels here with Toscanini, even if Munch lets the music breathe a bit more. This is still on the more urgent side, as was Munch’s habit. But when it comes to the main cathartic climax, this is played to the hilt. Indeed, Munch even speeds up marginally toward the big climax, something Toscanini also did. Ormandy is a worthy account too, but just didn’t move me as much.

Leonard Bernstein made two commercial recordings of Adagio for Strings, the first being with the New York Philharmonic from 1971 on Sony and the second with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra from 1982 on Deutsche Grammophon. Lenny being Lenny, he conducts this music as though it were Mahler, but in the case of the Adagio, I believe it works well. I am recommending both recordings because I believe Bernstein had a special affinity for American music. But his approach may not be for everyone, as he definitely tries to wring every bit of emotion possible from the score. This leads to longer playing time, the NYPO version is at 9:55 and the LAPO version is at 10:02, both among the longest on record. Bernstein’s vision of the piece takes its time to build, and there is obviously a great deal of thought in doing this. What I like about Bernstein is that while he is slow, he doesn’t create any exaggerated expressions, but rather just lets the music speak for itself. In the hands of a lesser musical god, the slower pace would not work. But for Lenny it does because every phrase is imbued with an almost devotional quality which doesn’t take any note for granted. The NYPO sound is somewhat closer, while the LAPO sound is warmer and more like a concert hall. Take your pick, they are pretty similar. This is music Bernstein was born to conduct.

American conductor Leonard Slatkin also recorded Adagio for Strings twice, both times with the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra. The first recording is from 1981 on the Telarc label, and the second is from 1989 on EMI (Warner). I hold a strong preference for the latter, it is more involving and better played. Slatkin moved from 7:37 for the first recording to 9:08 on the second recording, but it’s not just the slower pace that gives more satisfaction. It is also the sense of inevitability with a buildup to the main climax that is patient in getting there. There is a wistful quality to it, an almost hopeful tone at moments, until that original theme comes back with a passion. Slatkin is masterful at controlling the dynamics, and especially at pulling back the reins each time, taking us through cycles of emotion which of course eventually lead to the ultimate climax beginning at 5:30. There is tenderness and thoughtfulness here which I love. The sound is a bit recessed, but also warm and inviting.

The 1994 recording by Michael Tilson Thomas with the London Symphony Orchestra on EMI (Warner) is one of my favorites. You will notice right away the quite immediate sound, and in fact I had to turn down the volume on my headphones. But to be honest I quite like it, as it gives everything a bit of a three-dimensional quality. Pacing is moderate, even a bit on the quicker side, and I find Tilson Thomas emphasizes the tenderness and flow more than the schmaltz inherent in the piece. Some have labeled the performance “detached”, which is complete nonsense. The sense of forward pulse is maintained, and this is a good thing. It also gives us an individual view of the work which is still filled with emotion, but is not quite as sad or mournful. This is a performance which holds out for some hope in the end, and it is extremely well played. As I mentioned, the forward sound may not be to everyone’s liking.

A good find in my survey comes from another American conductor, Robert Spano, recorded with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra in 2009 on the Telarc label. First, I really like the sound quality on this recording, it captures the upper and lower registers well and the sound is immediate. Furthermore, Spano hits the emotional high points for me in terms of depth and poignancy. But the Atlantans also paint a beautiful canvas, sad as it may be. The wall of sound they create at around 5:15 onward is tremendous and the climax at 5:52 is as moving as any on record. This is outstanding really, and strongly recommended. It also helps that Adagio is on a well programmed album that includes John Adams’ fascinating On the Transmigration of Souls, as well as Barber’s own 1967 adaptation of Adagio for Strings into the choral Agnus Dei.

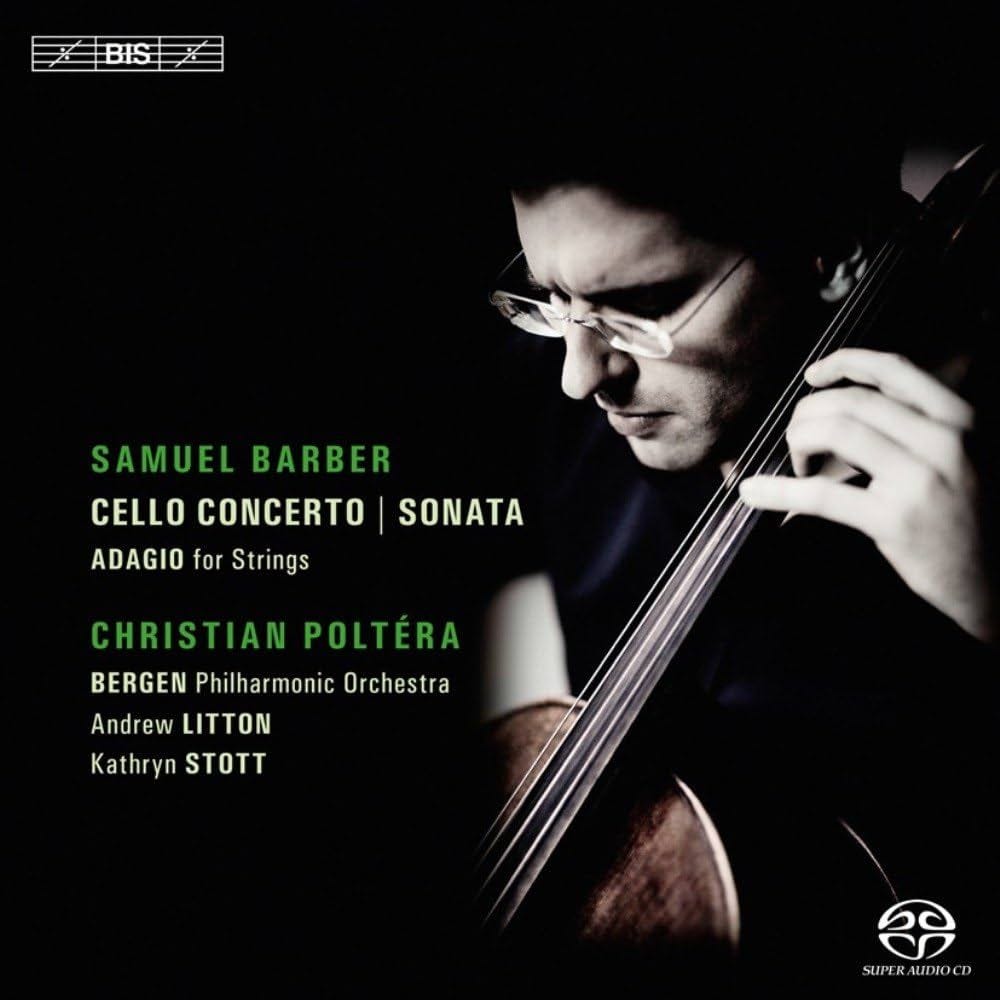

American conductor Andrew Litton made a marvelous recording of Adagio for Strings in 2009 with the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra on the BIS label. The way the piece opens as though the sound just fades in out of nowhere is well done, and the sound quality is outstanding. The pacing works quite well, and overall timing is at 9:01. Litton directs a reading of passion and depth, and similar to Schippers we can hear all parts of the orchestra incredibly well in a balanced picture. Dynamics are well controlled, and as things progress toward the main climax beginning from about 5:10 we are treated to refined strings which create a spacious glow. So, more in the mold of Schippers, Bernstein, and Slatkin, but none the worse for it.

Canadian conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s performance of Barber’s Adagio with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra from 2022 on the occasion of a benefit concert for Ukraine is highly recommendable. The recording was made live at the Met (Decca). The performance is on the somewhat quicker, more flowing side, and that is not a drawback at all. Indeed, there is something that feels so right about the pacing here, and even so there is certainly no lack of tension or pathos. This is a reading I believe Barber and Toscanini would have approved of, and Nézet-Séguin avoids any hint of vulgarity or odd interpretive intervention. The sound from the Met is a bit interesting, not altogether perfect, but the performance has a sense of occasion about it. In summary, this is a performance that rewards for its directness and relative lack of sentimentality.

Honorable Mention Recordings

I feel my recommendations above are solid, but perhaps more than some works on the survey, this is an extremely subjective list. Some of the recordings below are also excellent, but didn’t quite do it for me.

NBC Symphony Orchestra / Toscanini (RCA 1942)

The Philadelphia Orchestra / Ormandy (Sony 1957)

Academy-of-St.-Martin-in-the-Fields / Marriner (Argo/Decca 1976)

Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra / Slatkin (Telarc 1981)

Israel Chamber Orchestra / Talmi (Chandos 1987)

London Sinfonia / Hickox (Erato/Warner 1988)

Australian Chamber Orchestra / Tognetti (Sony 1992)

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra / Zinman (Argo/Decca 1992)

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Bychkov (Philips/Universal 1993)

Detroit Symphony Orchestra / N. Järvi (Chandos 1993)

Emerson String Quartet (DG 2002)

Royal National Scottish Orchestra / Alsop (Naxos 2005)

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra / Honeck (Reference 2013)

Vienna Philharmonic / Dudamel (Sony 2019)

Thanks again for reading! I hope you have enjoyed this installment on Barber’s Adagio for Strings. Next time I will be discussing Beethoven’s epic Missa Solemnis. See you then!

___________

Notes:

BaileyShea, Matthew (August 2012). "Agency and the Adagio: Mimetic Engagement in Barber's Op. 11 Quartet". Gamut. 5 (1): 7–38. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

Giordano, Diego. "Samuel Barber: Kierkegaard, From a Musical Point of View". In Kierkegaard Research: Sources, Reception and Resources (Series), Jon Stewart (ed.), Vol. 12, Kierkegaard's Influence on Literature, Criticism, and Art, Tome IV, The Anglophone World.

Gorman, Robert F. (2008). Great Lives From History: The 20th Century. Pasadena, California: Salem Press. p. 230. ISBN 9781587653452.

Henahan, Donal. (January 24, 1981). "Samuel Barber, Composer, Dead: Twice Winner of Pulitzer Prize". The New York Times.

Heyman, Barbara B. (2001). "Barber, Samuel (Osmond)". In Stanley Sadie; John Tyrrell (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan.

Kapilow, Rob. Barber's 'Adagio': Naked Expression Of Emotion. NPR online. March 9, 2010. Found online at https://www.npr.org/2010/03/09/124459453/barbers-adagio-naked-expression-of-emotion.

Lee, Douglas A. (2002). Masterworks of 20th Century Music: The Modern Repertory of the Symphony Orchestra. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93846-5.

Morin, Alexander (2001). Classical Music: Third Ear: The Essential Listening Companion. Backbeat Books. p. 74. ISBN 0-87930-638-6.

"NPR 100: Barber's 'Adagio for Strings'". NPR. March 13, 2000. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

Pollack, Howard (2023). Samuel Barber: His Life and Legacy. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-04490-8.

Schenck, Andrew. 1988. Booklet notes. Samuel Barber: Symphony No. 2; Music for a Scene from Shelley; Overture to The School for Scandal; First Essay; Adagio for Strings. The New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, Andrew Schenck, cond. CD recording. Stradivari Classics SCD 8012. Hackensack, New Jersey: Special Music Company.

Simmons, Walter (2004). Voices in the Wilderness: Six American Neo-Romantic Composers. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4884-8.

Stearns, David. (May 4, 2017). "Documentary sheds new light on fascinating West Chester composer Samuel Barber". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Tick, Judith; Beaudoin, Paul, eds. (2008). Music in the USA: a documentary companion. Oxford University Press. pp. 470–474. ISBN 978-0-19-513987-7.

Wise, Brian (September 8, 2010). "WQXR Features Barber's Adagio: The Saddest Piece Ever?". Retrieved August 30, 2012.

Wright, Jeffrey Marsh II (2010). The Enlisted Composer: Samuel Barber's Career 1942–1945 (PhD diss). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/samuel_barber_825394

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Barber?scrlybrkr=40ad99ec

Esta es una de las obras que a mi madre le traslada el espíritu.