Building a Collection #85

Requiem in D minor, Op. 48

By Gabriel Fauré

____________

“For me, art, and especially music, exist to elevate us as far as possible above everyday existence.”

-Gabriel Fauré

It is my pleasure to welcome back subscribers and regular readers, as well as any new readers, to Building a Classical Music Collection, where we have reached #85 on our survey (counting upwards) to the Top 250 Classical Works of All-Time. This series, redundantly titled Building a Collection is free to all subscribers. If you become a paid subscriber you will also receive an additional 3-4 posts per month in two other series: The Best New Classical Albums of 2025 (thus far there have been 17 albums covered this year) and The Top 75 Conductors (I just posted a profile of conductor Riccardo Chailly at #15 in that alphabetical list). If you would like a sample from those series, send me a message and I would be happy to send you a copy.

At #85 is Gabriel Fauré’s Requiem, one of the most sublime and uplifting choral works ever created. Up until the time of Fauré, most settings of the Roman Catholic Requiem (Mass for the repose of the dead) followed in the manner of Mozart and later Verdi with music that was hardly consoling. Indeed, it was downright frightening musically with a dramatic sense of foreboding and judgment pending upon the soul in a palpable way. By contrast, we have the Requiem of Fauré which is much calmer, filled with hope and consolation, and which delivers a peaceful send off for the deceased. Not only that, but Fauré evokes images of a reality where we are not met by a wrathful God, but rather a joy which words cannot express. It is one of my favorite works in all of music in the way it gives us hope and makes us look upon death in a different light.

Gabriel Fauré

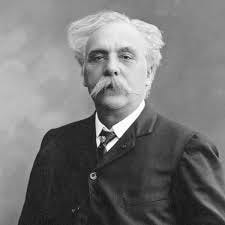

Gabriel Urbain Fauré (1845 - 1924) was a French composer, organist, pianist, and teacher who had a significant influence on French music in general and on other composers of his time. He did not come from a particularly musical family, and his father was a schoolmaster. Apparently there was a chapel attached to the school where his father worked where the young boy would steal away to and play on the harmonium (a “reed” or “pump” organ). In his own judgement he played terribly, but a blind woman that came to listen to him reported back to his father the young boy’s aptitude for music. When he was just nine years of age in 1854, his talent was recognized and he was sent to Paris to study the organ and to be a choirmaster.

As it turns out he would end up boarding at the school for 11 years, financially assisted by his home diocese. While there the young Gabriel would also learn harmony, counterpoint, piano, and composition. When Louis Niedermeyer, the founder of the school, passed away his organ class was taken over by none other than Camille Saint-Saëns, and this began a lifelong friendship between Fauré and Saint-Saëns. Fauré would credit the older friend with exposing him to the great masters, and for his part Saint-Saëns took the young man under his wing and spent extra time to go in more depth into detailed aspects of the craft. Their friendship lasted 60 years until Saint-Saëns’ death.

While Fauré would begin composing at a young age, few of his first attempts have survived. In any case, he didn’t have much time to compose after accepting his first position as a church organist at the Church of Saint-Sauveur, in Rennes. For four years, in addition to his normal duties Fauré also accepted numerous private students for piano lessons. Fauré didn’t especially like the job, felt unchallenged, and was not a man of strong faith. There are stories of Fauré rushing outside to smoke a cigarette during the homily, and he was eventually sacked for showing up one Sunday morning still in his prior evening’s clothes.

In 1870 Fauré volunteered for military service at the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, and he saw a considerable amount of action at Le Bourget, Champigny and Créteil. He was subsequently awarded the War Cross. France was defeated by Prussia, and in the aftermath Fauré fled to Switzerland and took up a post teaching at the École Niedermeyer which had taken up residence there to get out of Paris. His compositions from this period took on a darker, more somber note, similar to many of his fellow French composers. Upon returning to Paris, Fauré was appointed to a post at the Église Saint-Sulpice where he worked under the well-known French organ composer Charles-Marie Widor. He would also frequent salons in the city to hear the music of other composers such as Saint-Saëns and singers such as Pauline Viardot. Fauré became a founding member of the Société Nationale de Musique in 1871 which had the goal of championing French music. He joined other composers such as Georges Bizet, Emmanuel Chabrier, Vincent d'Indy, Henri Duparc, César Franck, Édouard Lalo and Jules Massenet in this effort.

Even though Fauré was an organist by trade and was extremely skilled, it seems he preferred the piano for his own enjoyment and compositions, as he left no organ compositions at all. In 1877 Fauré scored his first great success as a composer with his Violin Sonata no. 1. Later in 1877, Fauré was engaged to marry Marianne Viardot, daughter of Paulin Viardot, and there is every indication that he was in love with her. However, she broke off the engagement for unknown reasons. Saint-Saëns, in at least a partial attempt to distract the young man from his sorrow, took him to Weimar to meet Franz Liszt. Fauré liked traveling so much he began touring around Europe to see Wagner’s operas such as The Ring Cycle, Der Meistersinger, and Parsifal. While Fauré greatly admired Wagner, and knew his music well, it is interesting to note that unlike many composers of the day, Fauré’s music bears little Wagnerian influence.

In 1883, Fauré married Marie Fremiet, the daughter of a well-known sculptor. Biographer Jean-Michel Nectoux says she was "without beauty, wit or a fortune ... narrow and cold", though Fauré did have affection for her. Meanwhile, Marie was a homebody and did not enjoy going out like her husband. This would cause strain in the marriage, and Fauré had several affairs and dalliances outside the marriage. They had two sons together, the first of which Emmanuel Fauré-Fremiet went on to become a biologist of some renown. Their second son Philippe became a writer.

Fauré’s other love affairs took on something of a legend in the Paris salons, and women were apparently quite fond of him. After several on again, off again affairs, Fauré settled to some degree with a pianist named Marguerite Hasselmans who would essentially become his life-long partner while he kept her in a Paris apartment. Even though he was married, his relationship with Marguerite was well-known and open. During this time Fauré would continue working in his duties at the Church of the Madeleine, supplementing his income by teaching piano and organ lessons. What compositions he did create during those years, his publisher paid him a flat sum and therefore he received no royalties. In 1887 he composed the first version of his Requiem, his most well-known large-scale work, which would receive its final fully orchestrated treatment in 1901. Reportedly (and incredibly), the priest at the Madeleine was not impressed with the work and dismissed its use.

While Fauré was a happy, even carefree, young man, once into his 30s, Fauré would experience bouts of depression which we may only speculate about the cause. Perhaps his failed engagement, or perhaps his lack of significant success as a composer, or a combination of factors? An offer to compose an opera was aborted when the poet writing the libretto could not produce anything, which also sent Fauré into a deeper spiral so deep his friends began to worry. A friend invited him to Venice, where he recovered his spirits and began to compose more.

The 1890s saw fortunes improve for Fauré because he was given various positions at the Paris Conservatoire, and he was eventually appointed professor of composition in 1896. Among Fauré’s pupils were Maurice Ravel, Charles Koechlin, Louis Aubert, George Enescu, Alfredo Casella, and Nadia Boulanger. Ravel later noted Fauré’s open-minded approach to teaching, once admitting he was wrong in evaluating Ravel’s String Quartet. The musicologist Henry Prunières wrote, "What Fauré developed among his pupils was taste, harmonic sensibility, the love of pure lines, of unexpected and colorful modulations; but he never gave them [recipes] for composing according to his style and that is why they all sought and found their own paths in many different, and often opposed, directions."

In 1905, Fauré was appointed the head of the Paris Conservatoire, and stepped into a fractured environment owing to many feuds between traditionalists and modernists. Fauré instituted many changes in terms of admissions, how awards were judged, and the range of music which was permitted to be taught. In many ways, he opened the conservatory to broader horizons both in terms of looking back at baroque, classical, and romantic masters, but also in terms of looking ahead and being open to new methods and techniques. Indeed, he became a champion of new music. While his position left him in a good place financially, he still did not have the time needed to compose as he wished. Around 1910, Fauré began to go deaf, a condition that caused him both physical and emotional pain.

Fauré’s music slowly gained a following outside France, first in England followed by Germany, Spain, and Russia. After playing at Buckingham Palace in 1908, other opportunities opened up for him such as meeting Edward Elgar and hearing his First Symphony. Elgar subsequently tried to get Fauré’s Requiem performed in England, but that did not happen until 1937. After receiving more exposure, Fauré would also become friends with Tchaikovsky, Albéniz, Richard Strauss, and the young American composer Aaron Copland. When WWI broke out, some in Fauré’s circle (including Saint-Saëns) tried to ban German music in France. But Fauré never considered himself a “nationalist” composer, and disagreed with the effort to ban German music (even though his own music was never deeply loved by the Germans).

Fauré retired from the conservatory in 1920 due to deafness and frailty. He received the Grand-Croix of the Légion d'honneur, something very rare for musicians. The French president put on a public tribute to the composer, with the composer present, where they played all of his most well-known music. Even though Fauré could not hear any of it, he was pleased with the recognition. In his later years, his health declined even more, at least partially due to his heavy smoking. In his final year, under encouragement from Ravel, Fauré wrote a String Quartet he worked tirelessly on and which was finished less than two months prior to his death in 1924. It was not premiered until after his death. Fauré died from complications due to pneumonia in Paris in November 1924 at the age of 79.

In terms of his music, scholars have noted there is not so much difference between his early and late compositions. Chopin, Mozart, and Schumann were early influences, but in his later works can be heard foreshadowing of more modern and even atonal influences such as Schoenberg, as well as some jazz. The importance of harmony from his early studies remained throughout his career, though it became progressively more dissonant as time went on. In this sense, Fauré was somewhat of a forerunner to the impressionists. He still emphasized the uninterrupted flow of the musical line while making rhythmic changes more subtly.

Fauré is particularly known for his vocal art songs, the French equivalent to the German Lied. His songs number over one hundred, and span the entire length of his composing life. He also composed some song cycles around specific themes including Cinq mélodies "de Venise", La bonne chanson and later La chanson d'Ève and Le jardin clos. Fauré’s two existing operas have never made much of an impression, but his piano music certainly has. Major piano works include thirteen nocturnes, thirteen barcarolles, six impromptus, and four valses-caprices. They were composed across the years of his career, and are varied in style and mood. He also wrote some shorter, separate pieces such as Romances sans paroles, Ballade in F♯ major, Mazurka in B♭ major, Thème et variations in C♯ minor, and Huit pièces brèves. For piano duet, Fauré composed the Dolly Suite and, together with his friend and former pupil André Messager, an exuberant parody of Wagner in the short suite Souvenirs de Bayreuth. While influenced by Chopin and Schumann, Fauré’s piano works are known to be quite difficult to play and while his earlier works are happy and wistful, many of the later works are darker and unsettled. There are also few opportunities for a virtuoso to show off in these works, as Fauré consciously avoided composing for virtuosic effect alone.

Fauré apparently did not care for orchestration, and often turned to friends or pupils to help him with it. Thus, some of his orchestration is on the sparse, or simple side. He did not like ostentatious showpieces or having to resort to special effects for orchestral music. His best-known orchestral works Masques et bergamasques (Suite), Dolly, orchestrated by Henri Rabaud, and Pelléas et Mélisande. His Requiem, as we shall see below, is widely believed to have been fully orchestrated in its final version by someone other than Fauré, although we don’t know exactly who helped him.

As for Fauré’s chamber works, his two Piano Quartets are relatively well-known today, and he also wrote two piano quintets, two cello sonatas, two violin sonatas, a piano trio and a string quartet. Aaron Copland in his writing on Fauré deemed his Piano Quintet in C minor to be one of Fauré’s most brilliant works. His final String Quartet in E minor is also highly acclaimed, and held as one of the truly great string quartets written.

Requiem in D minor

Fauré’s Requiem, first written between 1887 and 1890, is his representation of the Roman Catholic Mass for the Dead in Latin, and it is Fauré’s most well-known and best loved work. We don’t know for certain who coined the term “A Lullaby for the Dead” to describe Fauré’s Requiem, but it certainly seems to fit because Fauré’s focus was consolation, tenderness, and eternal rest rather than the more terrifying aspects evoked by the requiems of Mozart, Verdi, and Britten. A more apt analogy might be to compare it to Brahms’ A German Requiem in terms of its humanity and solace, but then again Brahms uses other literary texts, German language, and a different structure other than the Latin Mass for his work.

Before going too far, it is important to note that there are really three different versions of the score for Fauré’s Requiem:

First Version (1888)

Fauré completed the first version of the Requiem in January 1888, and that first version only contained five of the seven sections:

Introït et Kyrie

Sanctus

Pie Jesu

Agnus Dei

In Paradisum

Thus the Offertoire and Libera Me were missing, and were added sometime later, but before 1893. The Libera Me that was eventually added was actually composed some 11 years prior to the Requiem as a solo for baritone voice. This original version asked for a choir of about 40, a combination of boys and men (at the time the Church of the Madeleine did not permit women choristers), solo boy treble, harp, timpani, organ, and strings. A few months later for a performance at the Madeleine, Fauré added horn and trumpet. You hardly hear this version played at all today for the simple reason that it is felt to be incomplete without the two missing sections. There have been some recordings made of this version, but I am purposely not including any recordings of this version in my recommendations.

Second Version (1893)

Fauré had continued to work on the piece, and in 1893 he finally felt it was ready to be published, but alas no publisher could be found at the time. While Fauré’s own manuscript survived, it was a complete mess overwritten many times with changes that may or may not have been Fauré’s own. A wonderful discovery was made in 1968 somewhere in the Church of the Madeleine of a set of the orchestral parts and a copy of the bass score with Fauré’s own annotations on it. Thus, several scholars began to try to put together a new edition of the entire Requiem, and in particular the Fauré scholar Jean-Michel Nectoux tried to do it in the 1970s. But the first 1893 edition to be published was by English conductor John Rutter in 1985 (by Oxford University Press), and this second version adds two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, and a baritone solo. It might be seen as a chamber-sized middle ground between the sparse original and the fully orchestrated version to come later. However, importantly Rutter did not have access to what had been found in 1968. Meanwhile, Nectoux’s edition was published in 1994. It took longer and includes scholarship from musicologist Roger Delage, but most importantly it DOES include the 1968 discoveries. Rutter’s version, though important, was really a makeshift until Nectoux’s more complete version was published. It includes some timpani and harp parts not present previously, as well as some other scoring. Rutter’s 1984 recording of the 1893 version was the first recording of this smaller sized chamber reading, but since then this has become a much more common edition to use for recordings. We also hear the solo violin part in the Sanctus in this version, something I personally love. It is known that Fauré's preference was for female voices in the choir, and for a soprano to sing the Pie Jesu if possible.

Third Version (1901)

The third and final version came about because his publisher urged him to score the Requiem for larger concert venues rather than just for liturgical use. This fully orchestrated version was completed in 1900 and published in 1901. The original copy does not survive, and so it is unknown whether Fauré himself completed it, or whether as many scholars believe, it was delegated to one of his pupils. There are some significant changes from the original 1888 version. This version is for mixed choir, solo soprano, solo baritone, two flutes, two clarinets (only in the Pie Jesu), two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets (only in the Kyrie and Sanctus), three trombones, timpani (only in the Libera me), harp, organ, and strings. During his lifetime, Fauré never made it clear which version he preferred. In some cases his references were to the original version or the 1893, while at other times he commented on how much he enjoyed the greater sound produced with a full orchestra. The recordings made up until 1984 were all of the 1901 edition, and it is still used for some recordings.

So in terms of what we hear in recordings today, there are seven sections as follows:

Introït et Kyrie

Offertoire

Sanctus

Pie Jesu

Agnus Dei

Libera me

In Paradisum

John Sinclair in his notes for the Bach Festival of Florida comments:

“Structured in seven movements, the Requiem begins with the Introit and Kyrie, which opens solemnly, almost monolithically, as if time has suddenly stopped. The entry of the voices in the Offertoire highlights one of Fauré’s lovely and mysterious modal melodies, sung in canon by the tenors and altos in close harmony as they plead for the freeing of the souls of the departed. The short Sanctus begins ethereally and rises to a triumphant climax before quickly settling back into its sweet reverie. Pie Jesu features the soprano soloist accompanied by simple harmonies. The Agnus Dei movement is introspective, expansive, and flowing. Libera Me is the most somber music of the whole Requiem, an impassioned plea for liberation and redemption. In Paradisum, the famous and otherworldly finale, brings the work to a prayerful closure in which the treble voices again float ethereally through a beautiful and simple melody.””

In a 1902 interview, Fauré commented: “It has been said that my Requiem does not express the fear of death, and someone has called it a lullaby of death. But it is thus that I see death: a happy deliverance, an aspiration towards happiness above, rather than as a painful experience.”

Aaron Copland commented further, “Those aware of musical refinements cannot help admire the transparent texture, the clarity of thought, the well-shaped proportions. Together they constitute a kind of Fauré magic that is difficult to analyze but lovely to hear.”

Recommended Recordings

Although I don’t have an essential recording for Fauré’s Requiem, there are loads of extremely good recordings out there. I have listed my favorites below, and several honorable mention recordings below that. A few things that I listen for specifically in this work:

The baritone entrance in the Offertoire should be relatively smooth with a soothing but full tone. This is not a place for the baritone to become operatic, it must be sung firmly but also with warmth and tenderness;

The Sanctus is a potential sticking point for me, clarity is essential, as well as gentleness and subtlety in the first half, and then when the big climax comes I want to hear power in the chorus without hitting the notes too hard and without hectoring. The contrast between the softer section and the climax must shake you to your core, this is the “wow” moment of the entire work, and it must have an impact. But if the voices or horns hit too hard, or for too long, it becomes overly profane for my taste. Also the horns must be heard, but again must also pull off quickly. The choir and the orchestra must become quiet again just as quickly as they grew.

In the Pie Jesu, I like an innocent sounding voice without too much vibrato, my imagination conjures up an angel singing this section. Therefore, clarity, perfect intonation, and articulation are desired. I don’t like sopranos that take too much of an operatic approach, nor do I like it taken too slow. This is a sacred song, and deserves the utmost reverence in my view. A boy treble voice, if done well, is even better because of the lack of vibrato and the clearer, purer tone.

I think the list below has a variety of different editions, including a few which use a boy treble rather than soprano as well. They are listed in chronological order by recording date as usual. Due to the sheer number of recordings, I will try to keep my summaries brief.

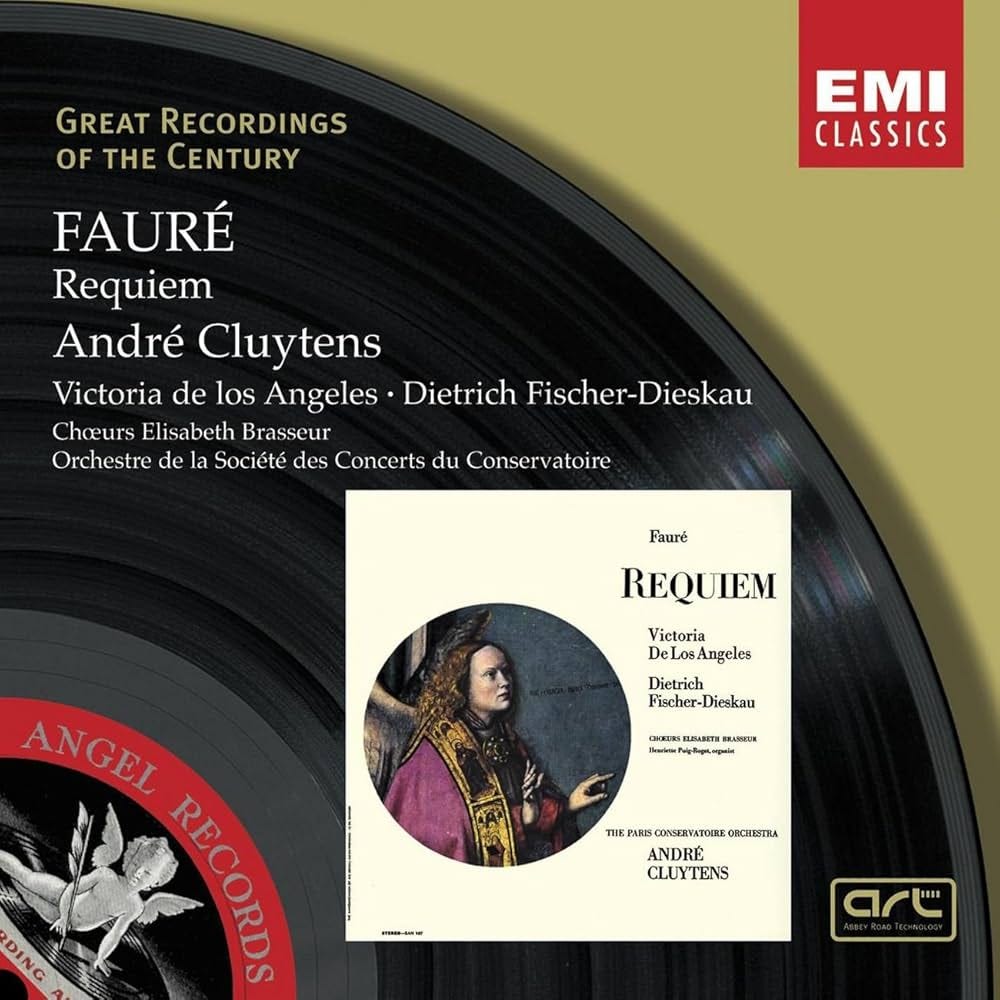

The first recommended recording is a classic on EMI/Warner from 1963 conducted by André Cluytens and he is joined by the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra and the Choeurs Elisabeth Brasseur. Soloists are baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and soprano Victoria de los Angeles. While the sound is a bit thick and creamy for Fauré, this was indicative of when it was recorded, and in any case the performance is beautiful. I questioned whether Fischer-Dieskau would have the subtlety and tenderness in his voice required for his parts in the Offertoire and Libera me, but it turns out he is superb. De Los Angeles was a superstar at the time, and she sings like it, but though some complain she is too operatic, I disagree. I find her quite affecting and moving. The choral work is very good, and Cluytens has a natural feeling for the character of each section. The 1901 edition is used, and soprano for the Pie Jesu.

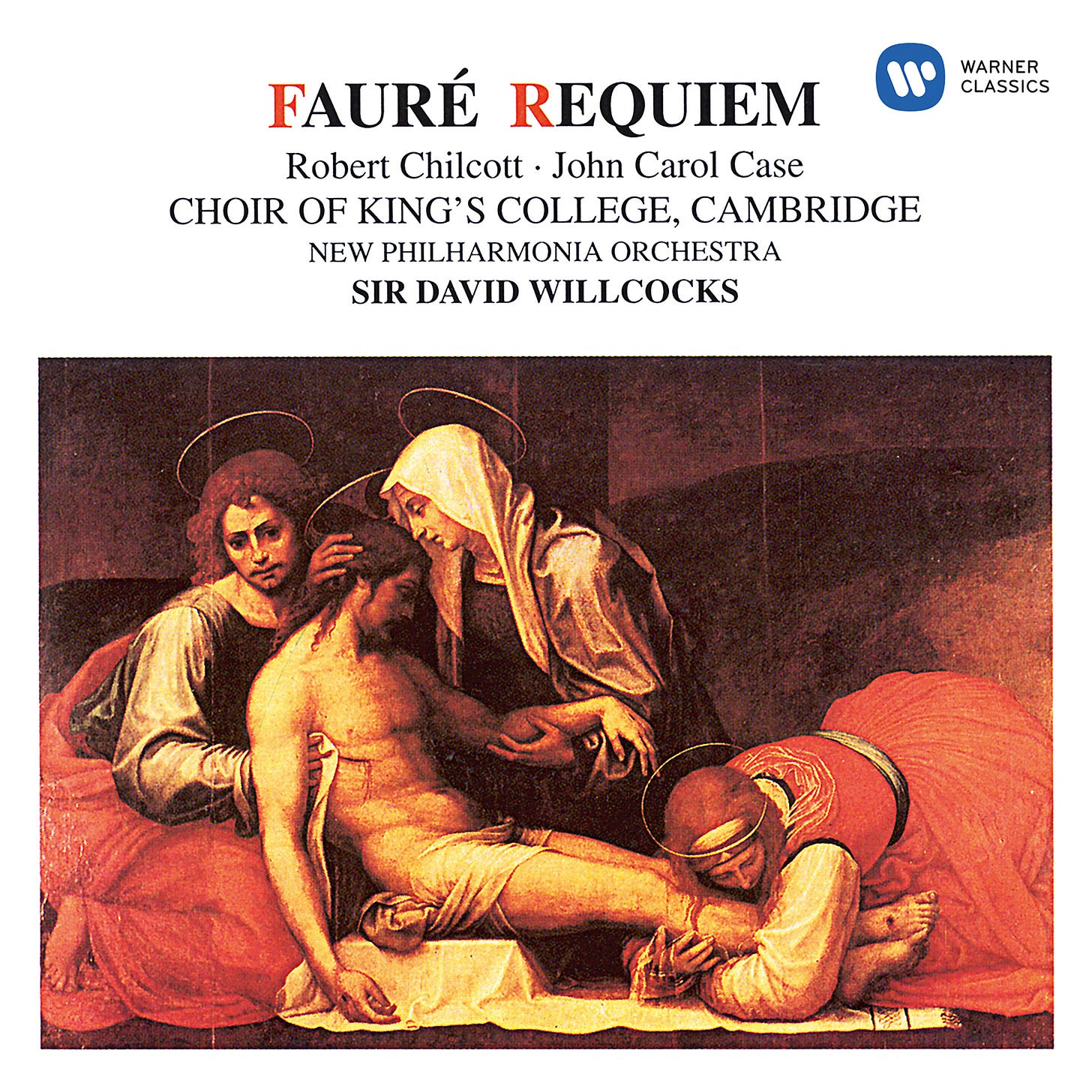

The 1967 recording on EMI/Warner with choirmaster Sir David Willcocks is another classic recording of this masterpiece, and he directs the New Philharmonia Orchestra and the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge. Soloists are baritone John Carol Case and boy treble Bob Chilcott. I must say when it is as well sung as Chilcott’s Pie Jesu, I actually prefer the treble to a soprano. This recording has been highly acclaimed, and in terms of a recording that best highlights English choral singing (without regard for whether this is what Fauré envisioned) , this is a particular favorite of mine. The clear voices are captured in good sound, the solos are delivered with an extra ounce of feeling, and the orchestral/choral balance is very well done. I just love the feeling of the entire performance, and the rich sound. The 1901 edition is used, and a boy treble is used for the Pie Jesu.

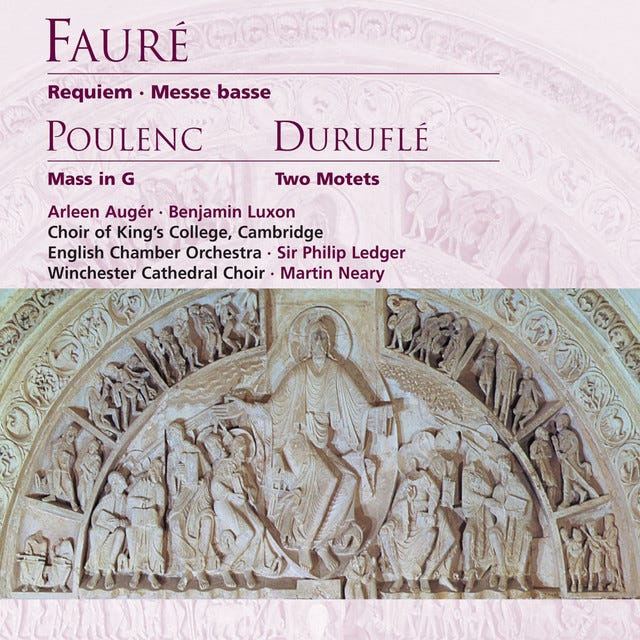

Similarly, the 1982 recording from Sir Philip Ledger on Warner (Classics for Pleasure) is also in the tradition of English choral singing, as he is joined by the English Chamber Orchestra and the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge. Soloists are soprano Arleen Auger and baritone Benjamin Luxon. Both soloists are outstanding, and I especially enjoy hearing Auger in her prime. The ECO has always been one of my favorite chamber orchestras due to their fullness of sound with nice transparency, and they deliver that here. The King’s College singers are once again outstanding, and remind me of the many albums of Christmas carols they have produced over the years. The sound is very good from the early digital years, and balances are well achieved. They use the 1901 edition and a soprano for the Pie Jesu.

In 1984 English composer and conductor John Rutter came out with his recording on Conifer (Collegium) with the City of London Sinfonia and The Cambridge Singers. Soloists are soprano Caroline Ashton and baritone Stephen Varcoe, with John Scott on organ and Simon Standage on solo violin. This album won a Gramophone Award in 1985, and it still sounds good. Of course there is the historical aspect that they performed Rutter’s own orchestration of the 1893 edition. Ashton is terrific in the Pie Jesu, and Varcoe is very fine too. The sound is not ideal, to me it is almost a bit grainy and lacks the depth of more recent recordings. It is certainly well played and detailed, and while some people swear by this recording, and I agree it is very good, I would not want it as my only version. The 1893 edition is used, and a soprano sings the Pie Jesu.

A sentimental favorite of mine is the 1986 recording by Richard Hickox and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the London Symphony Chorus on the MCA/RPO label (it was not available on idagio, but I found it on Spotify for streaming). Soloists are baritone Stephen Roberts, and boy treble Aled Jones (who became famous as a young singer, and has continued since with a very successful career). Once again in the English choral tradition, this version sounds wonderful to my ears and the chorus is clear and immediate in the sound. Hickox was a wonderful choral conductor in my view, and he leads an energetic but also detailed performance. Roberts brings an appropriately reverent tone, and the young treble Jones is beautiful, very likely the best treble Pie Jesu on record. Well worth hearing. The 1901 edition is used, and a treble sings the Pie Jesu.

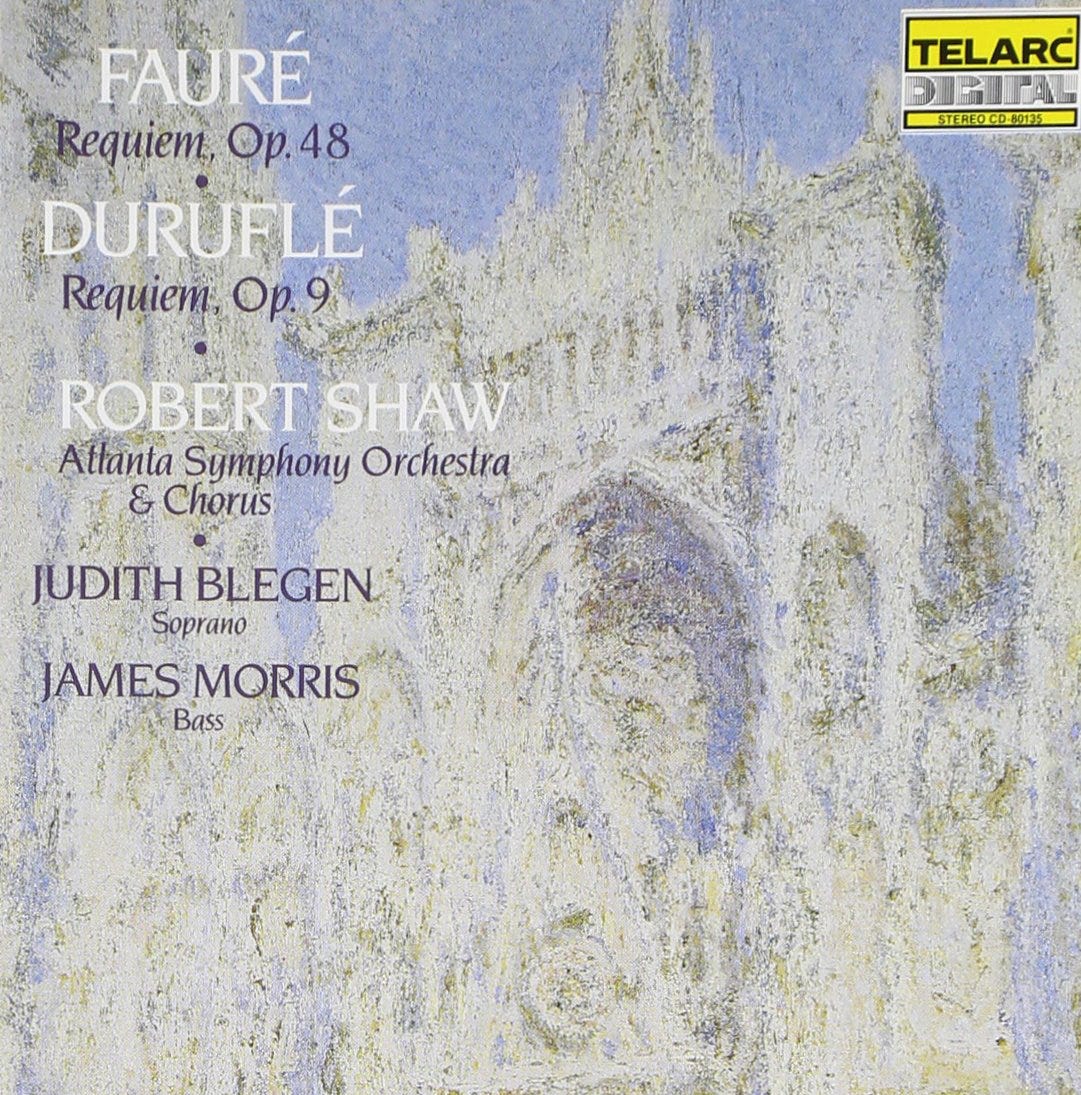

Also from 1986 comes a gloriously fully orchestrated recording from the famed choral director and conductor Robert Shaw joined by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chorus on the Telarc label. Soloists are soprano Judith Blegen and baritone James Morris. First, the sound is terrific, immediate, warm, and full. The chorus sounds (and is, of course) utterly American, which I have found annoying with some recordings, yet here I find no issue with their Latin. Blegen sounds wonderful, better than I recall her sounding on other recordings. Morris has a deep, dark baritone but he uses it with warmth and tenderness. Pacing is ideal, there is plenty of weight but also detail, and of course this was the kind of music Shaw was born to conduct. Around the same time they also recorded Verdi’s Requiem which garnered great reviews, but going back to it now I find it a bit flat. Not so here, this is one of Shaw’s greatest recordings. The 1901 edition is used, with a soprano on the Pie Jesu.

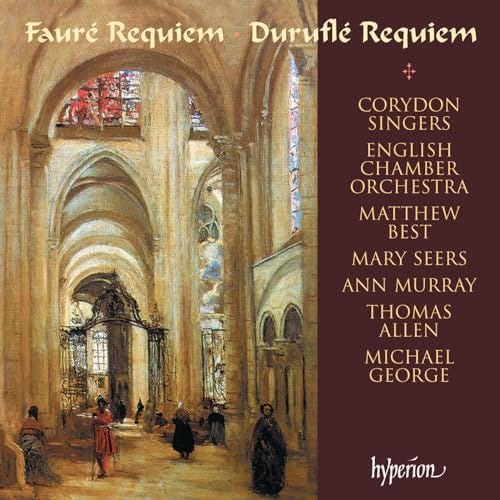

The 1987 recording by Matthew Best and the Corydon Singers joined by the English Chamber Orchestra on Hyperion is easily one of the finest recordings of this work. Soloists are soprano Mary Seers and baritone Michael George, and they both sing wonderfully. The recording has more of a “church” or liturgical feel to it, meaning that the performers are perhaps marginally less emotionally demonstrative than on some larger scale recordings. But the serenity is unmatched, and the gentle way it lifts your spirits is genuine and satisfying. The Hyperion recording sounds excellent, with warmth and depth but also nicely captured detail. Pacing is moderate, and dynamics are perhaps not as wide as elsewhere but that is not to say it has less impact. The more devotional approach is actually very appealing. The 1893 edition is used, and a soprano for the Pie Jesu.

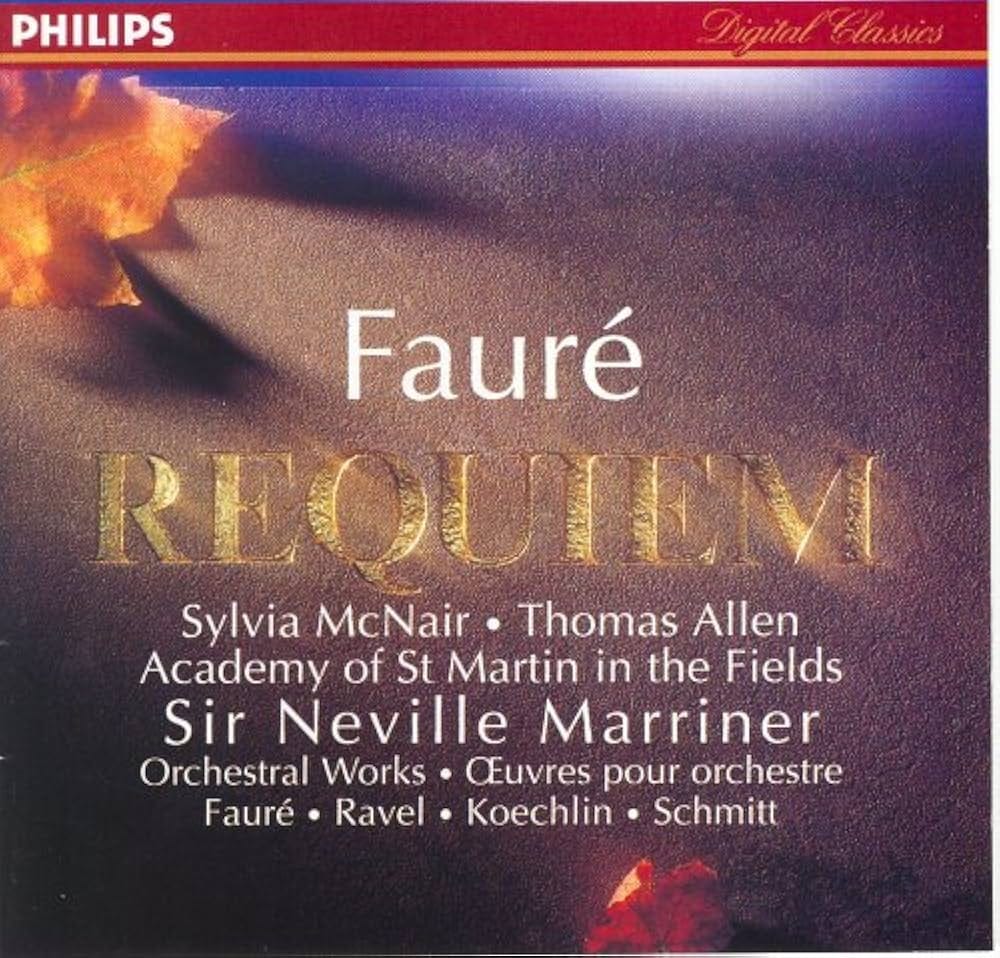

It might not surprise you to find Sir Neville Marriner on this list, and he did record the Requiem twice. However, it is his second recording from 1993 on Philips/Universal that is most recommendable. He is joined of course by the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields and Chorus. One of the main attractions here, at least for me, is the incredible voice of baritone Thomas Allen, one of my all time favorite singers. The soprano is Sylva McNair, at the height of her career at the time. Both are tremendous. Allen doesn’t disappoint, and brings singing of warmth, humanity, and tenderness. McNair is not quite as good, but still excellent. Like most Marriner productions, tempos are down the middle and dynamics are nothing crazy. It is perhaps a performance more geared toward the concert hall, but nothing wrong with that. The sound is very good. The 1901 edition is used, and a soprano for the Pie Jesu.

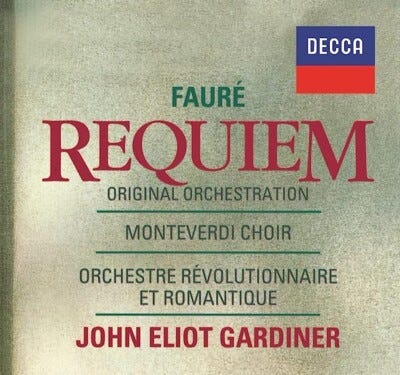

Few surveys of choral recordings are complete without mentioning John Eliot Gardiner, and while I am not a fan of the man, there is no questioning his credentials as a choral conductor. His 1994 recording of the Requiem on Philips (Philips/Universal/Decca) with his own Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique and the Monteverdi Choir is extremely well done, with soloists baritone Gilles Cachemaille and soprano Catherine Bott singing clearly and sensitively. Gardiner creates an atmospheric and ethereal effect with his pacing and use of the 1893 edition, and the acoustic of the Priory Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in Leominster, UK gives the performance a nice resonance. The performers are first rate all the way, and Gardiner infuses life and transparency into the recording as usual. The 1893 edition is used, and a soprano for the Pie Jesu.

The now late Japanese conductor Seiji Ozawa’s last several years in Boston were not the best artistically for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and there were more than whispers that Ozawa’s best years were behind him. Still, he was a terrific conductor of French music in particular, and his 1997 recording with the BSO and the Tanglewood Festival Chorus on RCA/BMG is one of his finest. The very good soloists are soprano Barbara Bonney and baritone Håkan Hagegård, both in fresh voice. Of course I’m a huge Barbara Bonney fan, and her creamy yet clear soprano is perfect for the Pie Jesu, and Hagegård is expressive and moving. The Sanctus is on the heavier side in terms of the climax, it certainly wakes you up, and is well done. Some may find it too heavy-handed, but Ozawa’s judgments elsewhere are superb, and the Tanglewood chorus sounds idiomatic and rich. To my ears, the louder passages suffer from some sonic overload which leads to a bit of distortion, but it could be my equipment. The 1901 edition is used, and a soprano for the Pie Jesu.

Yan Pascal Tortelier’s excellent Chandos recording from 2003 features the BBC Philharmonic and the City of Birmingham Symphony Chorus. The soloists are soprano Libby Crabtree and baritone James Rutherford. The recording is greatly aided by the radiant Chandos sound, which is full and sparkling. While Tortelier and forces may not get to the most depth in terms of atmosphere and interpretation, the beauty of this recording more than makes up for it in my view. Crabtree and Rutherford are both up to the task vocally as well as interpretively, and the chorus and orchestra are well balanced. This is a bigger boned performance than some others, but equally enjoyable to any of the recommended recordings on the list. The 1901 edition is used, and a soprano for the Pie Jesu.

The late Swiss conductor Michel Corboz held special affection for this work, as he performed and recorded it many times. But I especially enjoy his 2006 recording on the Mirare label with the Sinfonia Varsovia and the Ensemble Vocal de Lausanne. The soloists are baritone Peter Harvey and soprano Ana Quintans. The recording has wonderful presence, and the details and transparency are real assets. The 1893 version is used, so forces are a bit smaller, but I don’t notice any lack of weight. Both Harvey and Quintans are excellent, among the best I’ve heard, and the Lausanne chorus is outstanding. The acoustics of the Abbey of Fontevraud are more crisp than you might imagine, with a bit dryer acoustic than I would expect from a church. But this is good in my view, it gives a more intimate feeling, and the entire performance is devotional in nature. A beautiful recording which I heartily recommend. The 1893 edition is used, with a soprano for the Pie Jesu.

English conductor Harry Christophers has been making acclaimed recordings for a long time now, and his 2007 recording of the Requiem on the Coro label is recommended. Christophers leads the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, and the chorus of The Sixteen, as well as soloists soprano Elin Manahan Thomas and baritone Roderick Williams. Williams is as good in his parts as I’ve ever heard, really expressive and sensitive to the mood. Thomas is superb as well, and her Pie Jesu is clear and pure, just lovely. I have been a fan of The Sixteen for many years, but at times have felt they don’t pack enough of a punch. No concerns here, as they bring just the right amount of power along with a good amount of polish as well as that traditional English choral sound which is a bit hard to define. The Barbican acoustic in London is a bit dryer than I might want, but the clarity is there. It is a beautiful live performance, and even though the ASMF uses modern instruments, you might think it is a period performance given their lack of vibrato here. The 1893 edition is used, and a soprano is used for the Pie Jesu.

Nigel Short’s outstanding 2012 recording on LSO Live with the Tenebrae and the London Symphony Orchestra Chamber Ensemble features soloists soprano Grace Davidson and baritone William Gaunt. The entire team deserves praise here, but first mention goes to the choral group Tenebrae. They sing with precision and passion, giving us an equal amount of devotion and weight of sound, and it seems fully immersing themselves in the meaning of the text as well. Gaunt’s entrance in the Offertoire is profound, the Sanctus is deeply felt with Gordan Nikolic’s violin cutting through wonderfully, and Davidson’s Pie Jesu is haunting and pure. While most of LSO Live’s recordings have been made in the less than stellar acoustic of the Barbican in London, this one was made in Church of St. Giles which makes a huge difference in a sacred choral work such as this. Top notch recommendation. These use Rutter’s version of the 1893 edition and a soprano in the Pie Jesu.

The late English choral director and conductor Sir Stephen Cleobury had recorded the Requiem previously, but his most recent recording from 2014 is one of my top recommendations. Recorded for the King’s College own label, it features the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge. The soloists are boy treble Tom Pickard and veteran baritone Gerald Finley. We first notice the immediate and clear sound, which also gives a good amount of prominence to the organ, which is good of course. Cleobury uses a revised version of the original 1888 edition for which the two missing sections are added. Remember, there are fewer instruments in that edition, and the organ is more prominent. But as recorded in the Chapel of King’s College, this more devotional setting makes a lot of sense, and then of course you have the lovely and pure voice of the boy treble Tom Pickard and although he is no competition for Bob Chilcott or Aled Jones, he is still very affecting. Finley uses his voice very intelligently and never overpowers the accompaniment. Moreover, he is effective in his tender and prayerful delivery of the text. This recording uses the 1888 edition, with a treble singing the Pie Jesu.

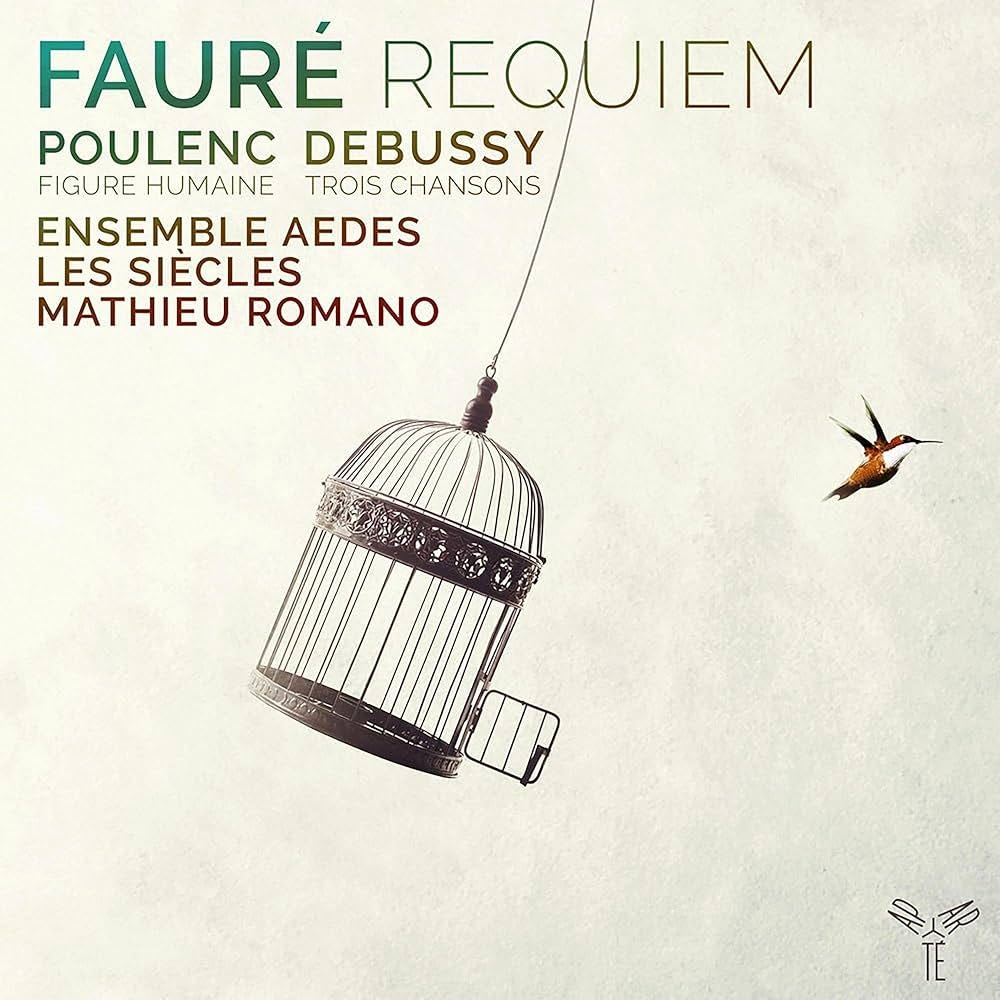

Finally, there is the excellent 2019 recording from the French conductor Mathieu Romano and the fine French orchestra Les Siècles joined by Ensemble Aedes on the Aparté label. I am struck by the precision of the choir, and the lovely transparent textures…just begin listening at 3’20” at the start of the Kyrie for some wonderful stuff. Baritone Mathieu Dubroca has an ideal voice for this music, not too heavy with not too much vibrato, and that matches the overall period feeling of the performance along with the period instruments of Les Siècles. Soprano Roxane Chalard’s Pie Jesu is not at the same level, in that she has more vibrato, slightly less control, and not the best diction, but nonetheless sings well. You may notice some of the French pronunciation of Latin from the choir especially, but I find it less distracting than on some other French performances, and in any case the style and beauty of the performance tends to override any concerns. There is a terrific sound from the instruments of the orchestra, and the balance with the choir is notably good. The 1893 edition is used, and as noted a soprano is used for the Pie Jesu.

That brings us to 16 recommended recordings if you can believe it. I think that is enough! But if you really can’t find one you like in the group above, check out the honorable mention recordings listed below as many of them are quite good as well.

Honorable Mention Recordings

Lamoureux Orchestra / Fournet (Decca 1953)

Orchestre de la Suisse Romande / Ansermet (Decca 1956)

New York Philharmonic / Boulanger (Diapason 1962)

Bern Symphony Orchestra / Corboz (Erato 1972)

Rotterdam Philharmonic / Fournet (Universal 1975)

Academy of St. Martin in the Fields / Guest (Decca 1976)

Philharmonia Orchestra / A. Davis (Sony 1977)

City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Frémaux (Warner 1977)

Orchestre national du Capitole de Toulouse / Plasson (Warner 1984)

Staatskapelle Dresden / C. Davis (Universal 1985)

Philharmonia Orchestra / Giulini (DG 1986)

Oblique / La Chapelle Royale / Herreweghe (HM 1988)

Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal / Dutoit (Decca 1988)

London Musici / Marlow (Conifer 1989)

Schola Cantorum / Summerly (Naxos 1993)

Philarmonia Orchestra / Legrand (Warner 1994)

Bournemouth / Hill (Warner 1996)

Gent / La Chapelle Royale / Herreweghe (HM 2002)

Netherlands / Spanjaard (Pentatone 2005)

Accentus / Equilbey (Naive 2008)

Orchestre de Paris / Järvi (Warner 2011)

Basel / Bolton (Sony 2019)

That wraps it up for Fauré's Requiem, and I want to thank you once again for reading and your interest in this great music. Join me next time for #86 on the survey, Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra. See you then!

____________

Notes:

Anderson, Robert (1993). Elgar. London: J M Dent. ISBN 0-460-86054-2.

Blyth, Alan (1991). Choral Music on Record. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36309-8.

Caballero, Carlo. "Review: Gabriel Fauré: A Musical Life", 19th-Century Music, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Summer, 1992), pp. 85–92 (subscription required).

Copland, Aaron. "Gabriel Fauré, a Neglected Master", The Musical Quarterly, October 1924, pp. 573–586 (subscription required)

Duchen, Jessica (2000). Gabriel Fauré. London: Phaidon. ISBN 0-7148-3932-9.

Jones, J Barrie (1989). Gabriel Fauré: A Life in Letters. London: B T Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-5468-7.

Landormy, Paul and M. D. Herter. "Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924)", The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 3 (July 1931), pp. 293–301 (subscription required).

Nectoux, Jean-Michel (1984). Gabriel Fauré: His Life Through Letters. Translated by J A Underwood. London: Boyars. ISBN 0-7145-2768-8.

Nectoux, Jean-Michel (1991). Gabriel Fauré: A Musical Life. Roger Nichols (trans). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23524-3.

Nichols, Roger (1987). Ravel Remembered. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-14986-3.

Nichols, Roger. "Fauré and Ravel", Gramophone, August 2000, p. 69

Oliver, Michael (1991). "Fauré: Requiem". In Alan Blyth (ed.). Choral Music on Record. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36309-8.

Orledge, Robert (1979). Gabriel Fauré. London: Eulenburg Books. ISBN 0-903873-40-0.

Prunières, Henry, quoted in Copland. (Copland spells the given name as "Henri" and uses the older English term "receipts" for "recipes".).

Ravel, Maurice (1922). "Les Mélodies de Gabriel Fauré". In Henry Prunières (ed.). Hommage musical à Fauré (in French). Paris: La revue musicale. OCLC 26757829.

Sackville-West, Edward; Desmond Shawe-Taylor (1955). The Record Guide. London: Collins. OCLC 500373060.

Sinclair, John V. GABRIEL FAURÉ Requiem, Op. 48. Online at https://www.bachfestivalflorida.org/faurs-requiem-program-notes.

Slonimsky, Nicholas. "Fauré, Gabriel (-Urbain)", Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, Schirmer Reference, New York 2001, accessed 8 September 2010 (subscription required)

Willmer, E. N. "Emmanuel Fauré-Fremiet, 1883–1971", Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, Vol. 18 (November 1972), pp. 187–221 (subscription required).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabriel_Faur%C3%A9?scrlybrkr=40ad99ec

![Fauré - The Cambridge Singers, Members Of The City Of London Sinfonia Directed By John Rutter – Requiem (1893 Version) And Other Choral Music – CD (Album), 1988 [r13521311] | Discogs Fauré - The Cambridge Singers, Members Of The City Of London Sinfonia Directed By John Rutter – Requiem (1893 Version) And Other Choral Music – CD (Album), 1988 [r13521311] | Discogs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!GEfe!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7cbc3bb8-b417-4872-9384-4e44f658f7a8_300x300.jpeg)

![Gabriel Fauré, Leonard Bernstein, Aled Jones – Requiem Op.48 / Chichester Psalm – CD (Album), 1986 [r8951425] | Discogs Gabriel Fauré, Leonard Bernstein, Aled Jones – Requiem Op.48 / Chichester Psalm – CD (Album), 1986 [r8951425] | Discogs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!BkJv!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F22b3f8fa-77b4-419a-bb01-8912b2d066d7_300x293.jpeg)