Building a Collection #82

Má vlast (My Fatherland)

By Bedřich Smetana

____________

A warm welcome to new and returning readers! On our long journey up the mountain of the top 250 classical music works of all-time, we are now at #82. In this slot is the epic Czech nationalistic set of tone poems titled Má vlast (My Fatherland) by the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana. I don’t have a drop of Czech blood (that I know of), and yet over the years this music has captured my heart and taken its place among my personal favorites.

Bedřich Smetana

Bedřich Smetana was born in 1824 in what was then Bohemia (now the western half of the Czech Republic), and died in an asylum in Prague in 1884. He is widely considered in his homeland to be the “Father of Czech Music” (although Dvorak and his advocates may object to that designation). In any case, Smetana was certainly one of the leaders of the movement toward musical nationalism.

As a youth, Smetana was not a good student except when it came to music. The famous composer and pianist Franz Liszt assisted Smetana in getting some of his music published, and later Smetana opened his own piano school. In 1860, Bohemia was granted autonomy by the Austro-Hungarian Empire and in the arts there was a desire to find some genuine “Czech” voices. A national theater was built, and soon thereafter Smetana composed his first opera The Brandenburgers in Bohemia, which premiered in 1866. It was a success, and he very soon thereafter composed The Bartered Bride which was to become his most popular and enduring opera, even though the opera was a failure when it premiered in 1866.

Má vlast

In 1874, Smetana had developed a ringing in his ears, a symptom from syphilis, that led to his complete deafness by the end of that year. It was during this time from 1874 to 1879 that he composed his symphonic masterpiece Má vlast. Unfortunately, there was lingering brain damage from the same syphilis that eventually led him to madness, and he died in an asylum in 1884. A period of national mourning was proclaimed, and he was buried at Vysehrad, one of the sites from Má vlast.

The six parts or tone poems of Má vlast are as follows:

Vyšehrad (The High Castle) – depicts the large castle on the southern outskirts of the city of Prague which overlooks the Vltava river and which has enormous historical importance to the residents of the city. The harp which opens the piece is a haunting and symbolic melody. The grand sweep of this poem reaches a bracing climax that is thrilling, representing temporary triumph, but then descends into desolation again symbolizing the fleeting glory of the Czech people. This is my personal favorite of the movements, even more than Vltava.

Vltava (The Moldau in German) – far and away the most popular and recognizable movement from Má vlast, this piece has often been performed and recorded on its own apart from the other five movements. The river’s course starts slowly, is joined at another place, and then grows into a broad flowing body of water passing through fields and forests. There are sounds of hunting horns arriving at the scene of dancing and celebrating at a wedding on the banks of the river. Here you can distinctly hear the lilt in the music, and as night falls the distant imagery continues, but softer as the river flows further down toward Prague.

Šárka – Šárka was a warrior heroine, the subject of operas, and here it is probably Smetana’s most dramatic poem of the six. Šárka’s story is told in the music, it is full of mood contrasts of beauty, vengeance, and violence. In the story, Šárka vows vengeance on the entire male race due to infidelity. It ends with Šárka and her companions slaughtering all the men without mercy.

Z českých luhů a hájů (“From Bohemia’s woods and fields”) – Smetana depicts Czech country life. There are momentary mood changes representing clouds and sunshine alternating, heard in minor and major harmony. According to Smetana, a country girl is walking through the fields and is struck by the beauty of nature on a summer’s day. A polka can be heard that has the country folk dancing.

Tábor – Tábor is a village in southern Bohemia which became a symbol for religious freedom due to it being a center for the Hussite movement in the fifteenth century. The main theme of the movement is a Hussite hymn. Tábor is strongly linked to the sixth poem by its final bars, so it is rarely heard performed on its own without Blanik following it.

Blanik – Blanik’s opening is a repeat of the end of Tábor , only louder and more emphatic. The story is told of the Hussites hiding out in Blanik mountain after they were outlawed. They fall into a deep sleep until the day they can come out to save their country. A shepherd boy can be heard on his pipe near the mountainside while the warriors sleep within.

There is no doubt Má vlast is somewhat bombastic and nationalistic in its themes. I happen to like bombastic and nationalistic music, but there is much more here too. There is great beauty, pastoral feelings, folk music at its most melodic, horn and trumpet calls, lovely sustained strings, and life-affirming themes. This is grand, epic music. Smetana was a great admirer of the tone poems of Franz Liszt, and he incorporated much of the design he had learned from Liszt’s works. He also admired Berlioz and Wagner, but Smetana was always able to maintain his own unique musical voice.

The Essential Recording

I have loved Má vlast since I bought a bargain CD decades ago with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra of London conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent (which takes its place in the honorable mention section below). But now having heard so many different versions, and in preparation for writing this essay I listened again to dozens of recordings, it is those conducted by Czech native Rafael Kubelik that I return to the most. Kubelik was one of the most respected conductors of the twentieth century, and made his reputation by conducting and recording large orchestral works of the nineteenth century. One of the composers he is most associated with is his compatriot Smetana.

Rafael Kubelik is associated with Smetana’s Má vlast more than any other work, and there are at least five commercial recordings available today on major music streaming services: his 1952 recording with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on the Mercury label, a 1958 recording with the Vienna Philharmonic on the Decca label, this one I’m highlighting from 1971 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra on the Deutsche Grammophon label, his 1984 recording with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra on the Orfeo label, and finally his historic 1990 recording with the Czech Philharmonic on Supraphon when Kubelik returned to his homeland to conduct at the Prague Spring Festival.

It is Kubelik’s 1971 recording from Boston that in my view is essential for this work. Be sure to listen to the 2008 remastered version of this recording, because it significantly improves upon the sound of the original remaster for CD. The sound is clearer, more immediate, and eliminates some of the muddy background noise. It is the performance by the Boston Symphony Orchestra that shines through, with not a hint of routine. They play with electricity, momentum, and commitment. The BSO brass shine through brilliantly, and Kubelik imbues this most versatile of American orchestras with Czech feeling and sentiment. The warmth and radiance of Boston’s Symphony Hall is also on display, and this is certainly Kubelik’s liveliest and engaging account of his several recorded versions. This recording clocks in at around 76 minutes, so it is a fine accomplishment to sustain the listener’s attention all the way through as this recording does. It feels like an event, like a special occasion, and that is why I return to the recording every chance I get.

Recommended Recordings

One of the finest recordings of Má vlast is from the Czech conductor Karel Ančerl and the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra on the Supraphon label from 1963. While Václav Talich and Rafael Kubelik made notable recordings prior to this, Ančerl has better sound and the CPO play with characteristic passion and depth. The Gramophone Magazine review of this recording says this reading is too low-key, but I disagree. All around this is one of the best performances, and maintains the idiomatic “Czech” sound.

The 1979 recording from Finnish conductor Paavo Berglund and the Staatskapelle Dresden on Warner is one of the top recommendations. The sound is rich, sumptuous, and detailed. The Dresden brass and woodwinds are burnished and warm, and Berglund brings out more than enough drama to rival any recording. If the performance lacks the last ounce of “Czech” feeling, it hardly matters when the music is played with such beauty and commitment. Berglund’s manner is direct, but also allows the overall flow to be maintained. Listening to this one again I concluded this is one of my favorites and deserves to be in the top tier.

The aforementioned live Rafael Kubelik recording from the 1990 recording with the Czech Philharmonic Supraphon was recorded at the Prague Spring Festival. During the years of communism, Kubelik had chosen to be in exile from his homeland. After a long illness and having not conducted for several years, Kubelik returned to Prague to conduct Má vlast in a concert celebrating the liberation of the country from Communist rule. It is worth finding the video of the performance on YouTube as well, as it is an historic and inspiring outing. Kubelik owned this work, but more than that it is clear that the piece was deeply meaningful to him. While the recorded sound is not perfect, it is perfectly fine and the extra dose of electricity from the event is palpable.

Another recording with nearly unbeatable sound is the 1995 traversal from Estonian conductor Neeme Järvi and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra on the Chandos label. While Järvi makes some unexpected tempo changes here and there, overall I find it works effectively. There is passion and quite a bit of energy, and I like how the brass can be easily heard as I believe they are a key to any Smetana performance. Järvi has the DSO sounding terrific here, and in my view this recording has flown under the radar for too long.

The late Australian conductor Sir Charles Mackerras and the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra recorded Má vlast live at the Prague Spring Festival for the Supraphon label in 1999, and this is another favorite recording. Mackerras specialized in music by Czech composers, and he brings a freshness to work that is appreciated. Mackerras could always be counted on for a new perspective, and the Czech PO bring their characteristic tart and woody tone to the proceedings. While perhaps not possessing the same sense of drama and occasion as Kubelik, this is really very fine and the sound is excellent, especially for a live recording. I appreciate the balance achieved here as well, with the orchestra front to back being heard well.

Sir Colin Davis’ recording of Má vlast with the London Symphony Orchestra on the LSO live label is from 2005, and after listening to it the past three days I believe it deserves to be recommended. Davis and the LSO would not be a logical choice for Smetana’s music, but in this case they deliver a performance which is direct, unassuming, and sharply etched. The dry acoustic of Barbican drains some of the warmth from the sound, but there is still plenty of drama and adrenaline. The LSO brass are terrific, and tempi are in the mainstream, perhaps slightly quicker here and there, but overall there is a feeling of rightness for me. This recording would not replace Kubelik or Ančerl for me, but I quite like Davis’ no nonsense approach. In fact, in the best way it reminds me of Malcolm Sargent’s recording I mentioned earlier. While perhaps missing some of the traditional Czech phrasing, this is a rousing Vyšehrad and the closing Blanik is triumphant. Meanwhile, the Moldau is nicely shaped and not too sentimental, which I enjoy.

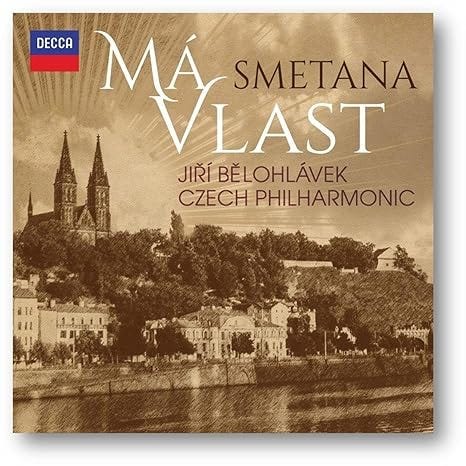

The late Czech conductor Jiří Bělohlávek was known throughout his career for his evocative performances of Czech music, including recordings by Suk, Dvořák, and especially Martinů. Some critics and scholars considered Bělohlávek the finest living advocate for Czech music until his untimely death in 2017. The 2018 release of this live 2014 performance of Má vlast with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra by Decca has perplexed me. Even though the recording was loved by the critics, the first several times I listened to it, I was left rather cold. But listening to it again, and on some better equipment, has completely changed my view. This is a thoroughly idiomatic performance, and when I listened closer, I can now hear what Bělohlávek was trying to achieve. The sound is warm and rich, although the acoustic is a tad reverberant, something which annoyed me initially. But with some headphone adjustments, I now realize how good this performance is, and that it stacks up well against the competition. It has some similarities with Kubelik’s final recording in Prague, as well as with Berglund in Dresden. I would not want to be without it, even if I would give the top nod to Kubelik.

Honorable Mention

The honorable mention list is substantial this time, with some really terrific recordings that for one reason or another gave me pause. But I would not let that stop you from checking them out.

Chicago Symphony Orchestra / Rafael Kubelik (Mercury/Decca 1952)

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra / Václav Talich (Andromeda 1954)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Rafael Kubelik (Decca 1958)

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra / Malcolm Sargent (HMV/EMI 1964)

Leipzig Gewandhausorchester / Václav Neumann (Edel 1966)

Orchestre de la Suisse Romande / Wolfgang Sawallisch (RCA 1978)

ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra / Lovro von Matačić (Orfeo 1982)

Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra / Rafael Kubelik (Orfeo 1984)

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra / Antal Dorati (Universal 1987)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / James Levine (DG 1987)

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra / Libor Pešek (Warner 1990)

Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra / Zdeněk Mácal (Telarc 1992)

Polish National Radio Symphony / Antoni Wit (Naxos 1994)

USSR / Vladimir Fedoseyev (Various 1994)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Nikolaus Harnoncourt (Sony 2003)

Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra / Theodore Kuchar (Brilliant 2006)

Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra / Claus Peter Flor (BIS 2011)

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra / Semyon Bychkov (Pentatone 2024)

Thank you once again for reading! I hope you have enjoyed this installment of Building a Collection. Join me next time for Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Symphony no. 2. See you then!

_______________

Notes:

Brennan, Gerald. Schrott, Allen. Woodstra, Chris. All Music Guide to Classical Music, The Definitive Guide. All Media Guide. Pp. 1286 - 1287, 709. Backbeat Books, San Francisco. 2005.

Macdonald, Hugh (2007). “Ma Vlast” (“My Country”) – A cycle of six symphonic poems. Boston Symphony Orchestra Program Notes, Week 8, 2007-2008 Season. Pp. 47-53.

Ottlová, Marta; Pospíšil, Milan; Tyrrell, John; St. Pierre, Kelly (2020). "Smetana, Bedřich [Friedrich]". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

A sleeper to try: Collegium 1704, Václav Luks . CD Accent. Very strange combination but great result. Better than many recent version, great energy