Building a Collection #81C

Roman Festivals (Feste Romane)

By Ottorino Respighi

____________

Welcome back and thank you for your patience on this third piece of the Roman Trilogy by Ottorino Respighi. The third tone poem from Roman Festivals (1928). While generally thought to be the least popular and least accomplished of the three works, it still packs a punch and has been a personal favorite of mine since the first time I heard it.

Ottorino Respighi

The biographical information below on Respighi is repeated from #81A (Fountains of Rome), so if you have already read the following, feel free to jump down to the information on the Pines of Rome.

The Italian composer Ottorino Respighi was born in Bologna, Italy in 1879 and died in Rome in 1936. Encouraged to pursue his interest in music from a young age, Respighi would eventually become one of the leading composers of the early 20th century. Respighi’s works span operas, ballets, orchestral suites, songs, chamber music, concertos, and transcriptions of 16th to 18th century Italian music. However, it was his three kaleidoscopic orchestral suites that form the “Roman Trilogy” (The Fountains of Rome, The Pines of Rome, and Roman Festivals) which brought him international fame and that continue to live on in frequent recordings and performances.

After taking lessons in violin and piano as a youth, Respighi enrolled at the Liceo Musicale di Bologna where he continued his music studies. For a few seasons he was the principal violinist at the Russian Imperial Theatre in Saint Petersburg, and it was during that time he met the Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. He took some lessons from Rimsky-Korsakov, and Respighi’s compositions would eventually show some definite influence from the great Russian. Giuseppe Martucci, Respighi’s composition professor in Bologna, would later say of him, "Respighi is not a pupil, Respighi is a master."

Respighi relocated to Rome in 1913, where he would remain for most of the rest of his life between short periods in Bologna. In Rome he would take the position of professor of composition at the Liceo Musicale di Santa Cecilia. While continuing to teach a bit, from 1923 onward Respighi focused most of his time on composition. Once he began to develop an international reputation, Respighi toured other countries, often guest conducting his own works in the United States, South America, and Europe. While working on his opera Lucrezia in 1935, Respighi became ill with bacterial endocarditis. He died four months later at the age of 56. His wife Elsa would survive him by some 60 years, tirelessly championing her husband’s music for the rest of her life.

Respighi’s great gift was putting into music the visual images and emotions evoked by cherished places. In particular, his orchestration is often colorful and exquisite in detail, but also contains a lot of charm and beauty. In terms of music history Respighi falls somewhere between the Romantic and the Avant-Garde or modern time periods, but is often considered to be “neoclassical”, meaning his compositions are highly tonal, accessible, and relatively easy to understand. He wrote a great deal of programmatic music, or music that is meant to depict ideas or images that are non-musical in nature. In other words, there is a background narrative driving the music. Italian music was undergoing a revival after World War I especially, and Respighi began studying Italian Medieval and Renaissance music. He either transcribed works (which is where a composer rewrites a piece of music, either solo or ensemble, for another instrument or other instruments than which it was originally intended) or borrowed some themes or snippets from ancient works. He did this most famously in another popular work, Ancient Airs and Dances for orchestra.

There is much evidence, including Respighi’s own comments, to suggest that his goal was to become a great opera composer. No doubt he would have been greatly influenced by the operas of Italian compatriots Giuseppe Verdi and Giacomo Puccini. But even though Respighi would compose several operas, none of them took hold with audiences and critics. Indeed, even his other compositions attracted little attention until he composed The Fountains of Rome, finished in 1916. Respighi worked a few times with the famous Russian ballet impresario Sergei Diaghelev, most notably creating the ballet La boutique fantasque, after Rossini in 1918. Several other Respighi compositions went on later to become well-known, including Gli uccelli (The Birds), Trittico botticelliano (Three Botticelli Pictures), Impressione brasiliane (Brazilian Impressions), and Il tramonto (The Sunset).

Roman Festivals (1928)

The four movements of Roman Festivals describe musically a scene of celebration in ancient and contemporary Rome, specifically gladiators battling to the death, the Christian Jubilee, a harvest and hunt festival, and a festival in the Piazza Navona. It is the longest of the triptych, and is said to be the most demanding to play as well. Legendary Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini led the premiere in February 1929 at Carnegie Hall in New York with the New York Philharmonic.

Even if Roman Festivals is not as highly regarded as Fountains and Pines (an assessment I don’t share), Respighi is still very successful at depicting images and sounds through his imaginative orchestration, his ingenious use of harmony and dissonance, and his assertive and sometimes brutal rhythmic drive.

Edward Yadzinski describes each of the four movements:

"Circenses" ("Circus Games" or "Circus Maximus")

"Il Giubileo" ("The Jubilee")

"L'Ottobrata" ("The October Harvest" or "The October Festival")

"La Befana" ("The Epiphany")

Circenses (Circus Games) depicts the ancient contests in which gladiators battled to the death, with the sound of trumpet fanfares. Strings and woodwinds suggest the plainchant of the first Christian martyrs which are heard against the snarls of the beasts against which they are pitted. The movement ends with violent orchestral chords, complete with organ pedal, as the martyrs succumb. Il Giubileo (The Jubilee) portrays the every-fiftieth-year festival in the Papal tradition (see Christian Jubilee). Respighi quotes the German Easter hymn, "Christ ist erstanden". Pilgrims approaching Rome catch a breath-taking view from Mt. Mario, as church bells ring in the background. L'Ottobrata (The October Harvest) represents the harvest and hunt festival in Rome. The French horn solo celebrates the harvest as bells and a mandolin portrays love serenades. La Befana (The Epiphany) takes place in the Piazza Navona. Trumpets sound again and create a festive clamour of Roman songs and dances, including a barrel organ and a drunken reveler depicted by a solo tenor trombone.

Recommended Recordings

I suppose you could say I am a bit particular about my Roman Festivals. I want it to be brash and almost garish in effect, especially Circenses and La Befana. There must be forward thrust and drive, and I would like to hear all the instruments clearly, even in the cacophony of sound.

The first recording that gets it right for me is Arturo Toscanini’s 1942 recording with The Philadelphia Orchestra on RCA (Sony). This is a fierce, intense reading led with characteristic fire by Toscanini, the man that conducted the premiere. While Roman Festivals has benefited in recent decades from the improvement in sound reproduction and recording techniques, capturing the larger than life orchestration, Toscanini and the Philadelphians sound remarkably good for 1942. But it is the performance itself which leaves a deep impression, the brass in particular being especially memorable. Just listen to Circenses, it is the perfect balance of control and abandon, and even the percussion can be heard relatively well. L’Ottobrata is fresh and lively, and La Befana will knock your socks off (despite the flubbed trumpet note at about 3’40” into La Befana). Toscanini’s NBC version from just a few years later in 1949 is also very good, but is less dramatic and the sound is not vastly better.

I have always loved the Leonard Bernstein recording of Roman Festivals from 1970 with the New York Philharmonic on Sony, and going back to hear it again just confirms it. First, the sound is up front and immediate, and it may be too present for some listeners. But I love it, and find that Bernstein balances the two main sections of brass and percussion where they both have a big impact, but don’t swallow up the strings. The tam tam strikes splash wonderfully, and the brass are full and menacing. The over the top personality of this work matches Bernstein’s own personality well, and he plays up the more exaggerated parts to the hilt. It could be mistaken for a film score, such is the high level of drama achieved. Tempos are pushed, but never out of control. If only technology (or the recording venue) had permitted just a tad more bass to come through, but as it is the sound is still very good. Giubileo has more presence and pace than heard on other recordings, and this is all to the good. It still carries mystery and delight as it transitions to a more lyrical, major key mood at about 4’10”. The fanfare that follows is majestic, but not at all sentimental, and we once again hear the wonderfully percussive orchestral writing. L’Ottobrata dances along at a quick pace, never breathless, but with a purpose and with all the details heard marvelously, the second half slowing down to showcase the violin solo at about 5’10”. This La Befana is the best ever recorded in my opinion, perhaps rivaled by Toscanini and Maazel, but they don’t have the same overwhelming impact for me. This is good stuff.

Speaking of Lorin Maazel, I still go back to his 1976 recording of Roman Festivals on Decca with the Cleveland Orchestra to hear one of the finest accounts of this work. Of course we have vintage Decca sound to thank for the rich and detailed sound picture, as well as the wonderful acoustics of the Masonic Temple in Cleveland, but Maazel leads a completely idiomatic performance which has loads more drive and personality than his later Pittsburgh version on Sony (even though that later one boasts terrific sound). This is not quite as brash as Bernstein, but may be preferred for some, and it has just as much going for it in terms of intensity. Listen from 1’30” in Circenses for some amazing brass work, as well as the strings and percussion. The depth and presence, as well as the virtuosity of the Clevelanders is stunning. The brass are given a slightly forward place compared to the percussion, but this works quite well. Giubileo is more refined and well considered than Bernstein’s account, giving the entire movement more weight and pathos. Maazel takes a similarly brisk approach to L’Ottobrata as Bernstein, and once again the Decca sound wins here. Maazel has sparkle and panache to spare, and it is easy to see why this work is a “orchestral showpiece” when it is played as well as it is here. The strings are glorious in the second half of L’Ottobrata as well, and pacing and dynamics are ideal from Maazel. La Befana doesn’t pack quite the same punch as Bernstein’s version, but this is still very substantial and perhaps more well balanced. The brass are spectacular, rhythms are crisp, and Maazel manages the cacophony in Piazza Navona superbly. Hugely enjoyable.

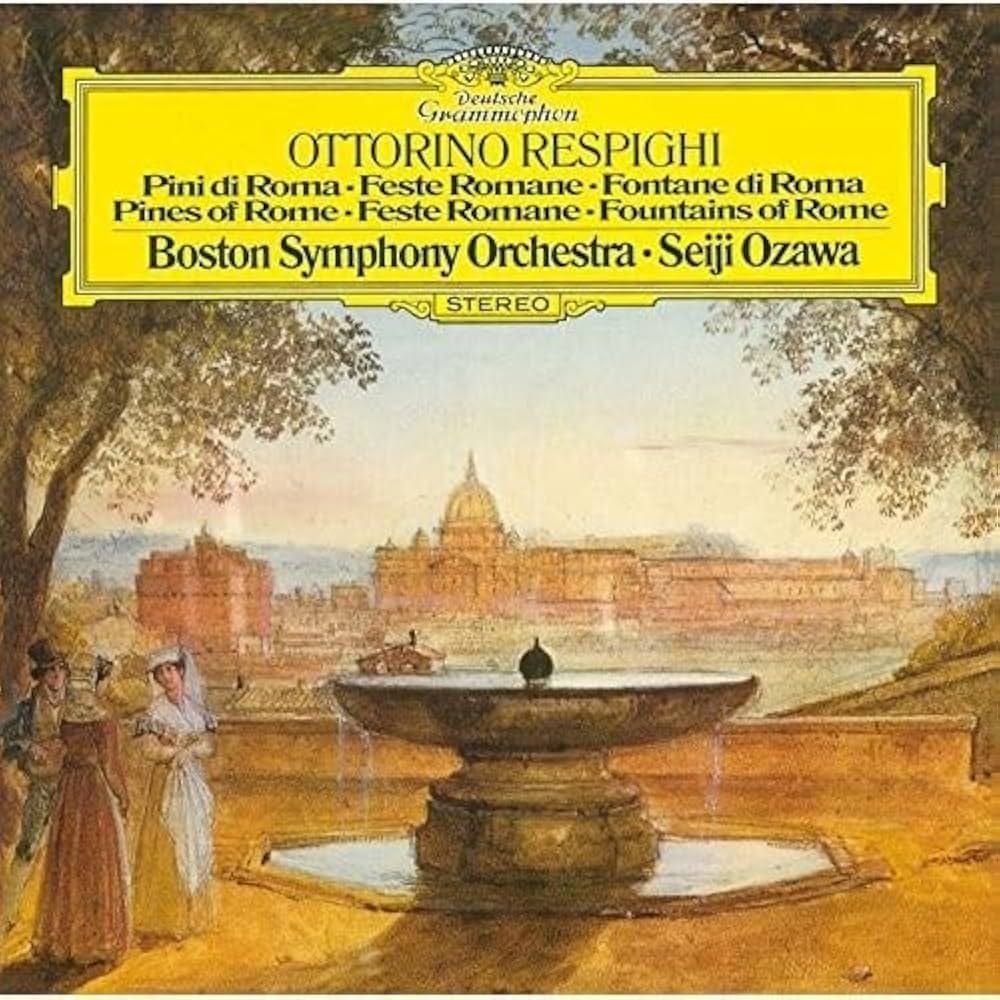

The 1979 recording of Roman Festivals by Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony Orchestra for Deutsche Grammophon remains one of my favorites, and I believe one of Ozawa’s best recordings. The BSO brings all the virtuosity and panache required, and the percussion and brass are up to the challenge. Ozawa is never plodding, and all involved sound engaged and at the top of their games. At the time when this recording was made, the BSO and Ozawa still had a good relationship and could still produce world class performances, and this was one of their best collaborations. Ozawa, ever sensitive to rhythmic considerations (he was an outstanding ballet conductor), has the measure of how to emphasize the pounding and pulsating aspects of this work better than most. I also like how at the end of La Befana he doesn’t push the tempo forward too fast, but rather lets the tension uncoil naturally with the coda and the final three notes. The sound is the best of DG analog sound, recorded shortly before the digital era. There is warmth and detail in equal parts, and Symphony Hall, Boston provides realistic resonance.

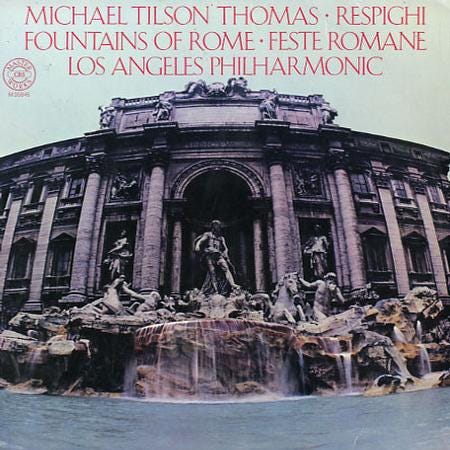

At the time Michael Tilson Thomas recorded his Respighi album with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra in 1980, he was only 36 years old. As I’ve contended previously, Tilson Thomas seemed to make some of his finest recordings when he was younger, and his Roman Festivals is another example. The sound has a wide dynamic range, and the CBS Masterworks (now Sony) recording has plenty of depth and detail. Tilson Thomas was a natural at conducting 20th century music, especially composers such as Stravinsky, Copland, and Debussy. So, it is no surprise that his Respighi is clear, alert, driven, dynamic, and exciting, and I cannot understand why this recording was out of print for so long. It is available on streaming services now, and I believe it is one of the best versions available. I particularly like Circenses and La Befana, but the whole thing is recommendable.

Riccardo Muti appears again as a recommendation for Roman Festivals, joined again by The Philadelphia Orchestra in a recording from 1985 on EMI (now Warner). Similar to his other installments of this triptych, Muti packs a wallop with forward sound and powerful brass and percussion. The Italianate flair is here as well, so once again this is not a version for the faint of heart. Muti’s full-blooded approach pays dividends in creating a cacophony only surpassed by Bernstein, and in this music that is a compliment. As other reviewers have noted, there is an open, almost garish quality to the sound, but I love it. Muti knows when to push forward, and when to pull back, and we happily hop on board for the ride. There is no backing off (a la Ozawa) at the conclusion of La Befana, but rather a pushing forward of the tempo until the last three notes are played quite close together, creating a smashing effect. This must stand as one of Muti’s greatest accomplishments on record.

We encounter Mexican conductor Enrique Bátiz once again for Roman Festivals, a part of his terrific 1991 recording of Respighi’s triptych with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra on the budget Naxos label. The recorded sound is rather forward, which does give more weight to the brass and percussion, but I also believe it helps this work come alive. Bátiz, similar to Muti and Bernstein, takes an epic view of the work as a whole, but doesn’t give up atmosphere and lyricism for mere brashness and volume. The acoustic is a tad reverberant, but this only adds to the lingering effect of the percussion and brass, which works well here. The RPO makes the most of Circenses and La Befana in terms of power, and Giubileo has a moving simplicity about it. The second half of L’Ottobrata is wonderfully lyrical and full of character. The conclusion is fully satisfying.

Finally on the recommended list is Antonio Pappano’s 2007 recording on EMI (Warner) with the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Pappano once again showing that this music is ideal for his approach. Pappano speeds up toward the end of Circenses, creating a terrifically visceral impact. Giubileo has a lovely singing quality about it, nicely evoking the Eternal City. La Befana has swagger and playfulness and is nicely balanced without going over the top too far. If the cumulative effect is not as overwhelming as Bernstein or Muti, that is just fine. The beauty of the playing is memorable, and Pappano never forgets to maintain the musical line no matter how raucous it becomes. The sound is not as spectacular as some but is perfectly good. Along with his Fountains and Pines, this triptych together is one of the best versions available.

Honorable Mention

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / de Sabata (DG 1939)

NBC Symphony Orchestra / Toscanini (Sony 1949)

London Symphony Orchestra / Goosens (Everest 1963)

Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal / Dutoit (Decca 1983)

Oregon Symphony / De Priest (Delos 1987)

Philharmonia Orchestra / Tortelier (Chandos 1991)

New York Philharmonic / Sinopoli (DG 1991)

Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra / Lopez-Cobos (Telarc 1992)

Santa Cecilia / Gatti (Conifer/RCA 1996)

London Philharmonic Orchestra / Rizzi (Warner 2000)

São Paulo / Neschling (BIS 2008)

Dallas Symphony Orchestra / Mata (Sono Luminus 2011)

Sinfonia of London / Wilson (Chandos 2019)

RAI Torino / Trevino (Ondine 2022)

Thank you once again for joining me on this journey! I very much appreciate your readership and support for Building a Collection. That wraps up our survey of Respighi’s Roman Trilogy. Join me next time when we will cover Bedřich Smetana’s nationalistic masterpiece Ma Vlast. See you then!

______________

Notes:

Blain, Terry (29 June 2012). "Composers - Respighi, Ottorino: The Roman Visionary". BBC Music Magazine. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

Brennan, Gerald. Gailey, Meredith. Lewis, Uncle Dave. Minderovic, Zoran. Rodman, Michael. Schrott, Allen. Woodstra, Chris. All Music Guide to Classical Music, The Definitive Guide. All Media Guide. Pp. 1089-1090. Backbeat Books, San Francisco. 2005.

Duchen, Jessica (February 2012). "Balancing Act". Opera News: 18–22.

Ferguson, Donald N. (1968). Masterworks of the Orchestral Repertoire: A Guide for Listeners. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-816-65762-9.

Freed, Richard. "Program notes to Feste romane". Kennedy Center. Archived from the original on 2018-10-17. Retrieved 2019-10-05.

Heald, David (2006). Respighi - Preludio, Corale e Fuga, Burlesca, Rossiniana, Five Etudes-Tableaux (PDF) (Media notes). Gianandrea Noseda, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. Chandos Records. CHAN 10388. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

Hurwitz, David. Respighi: Roman Trilogy/Pappano. Review online at https://www.classicstoday.com/review/review-14254/.

Klein, Herbert (January 2, 1929). "Respighi tells plans for work". Los Angeles Evening Post-Record. p. 11.

Ottorino Respighi: A Dream of Italy 1982, 15:36–15:50.

Perry, Tim. RESPIGHI Roman Trilogy Review. http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2007/nov07/respighi_trilogy_3944292.htm

"(Program notes)" (PDF). University of Washington Symphony Orchestra. 2007. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

"The Three Arts". The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland). 28 December 1920. p. 12 – via newspapers.com.

Webb, Michael (2019). Ottorino Respighi: His Life and Times. Troubador Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-789-01895-0.

Yadzinski, Edward (2019). "Respighi: Roman Trilogy" (PDF). JoAnn Falletta and Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra. Naxos Records. 8.574013. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

https://santacecilia.it/en/orchestra-and-chorus/orchestra/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transcription_(music)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottorino_Respighi

![Respighi – Riccardo Muti, The Philadelphia Orchestra – Pini Di Roma · Fontane Di Roma · Feste Romane – CD (Club Edition, Reissue), 1988 [r5340213] | Discogs Respighi – Riccardo Muti, The Philadelphia Orchestra – Pini Di Roma · Fontane Di Roma · Feste Romane – CD (Club Edition, Reissue), 1988 [r5340213] | Discogs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!_MEf!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa47e6672-ed89-4168-a6f2-32f22cc1668f_599x594.jpeg)