Building a Collection #74

The Six Cello Suites, BWV 1007–1012

By Johann Sebastian Bach

________________

Welcome back to everyone, I am thrilled you are here to join me on this journey through the greatest classical works of all-time. We are at #74 and in this spot are the six Cello Suites BWV 1007-1012 for unaccompanied cello by Johann Sebastian Bach. The suites contain some of the most beloved music ever composed by Bach, and this is the sixth composition in our survey by him.

Johann Sebastian Bach

In terms of biographical information on Johann Sebastian Bach, there are many resources online and in print. For some general information, I refer you to my post from June 19, 2022 which contains more information about Bach the man and composer. Here is the link to that post:

The Six Cello Suites

It is believed that Bach composed his six suites for unaccompanied cello between 1717-1723, during the time he was the Kapellmeister in Köthen in Germany. Following the traditional structure of the Baroque suite, each begins with a Prelude followed by movements representing various forms of baroque dance. In the case of Bach’s Cello Suites, there are six movements each: prelude, allemande, courante, sarabande, two minuets or two bourrées or two gavottes, and a final gigue. Musicologists and critics have lavished praise on Bach’s Cello Suites, and many consider them to be the pinnacle of his artistry.

In modern times, the Cello Suites were virtually unknown to most listeners until the 13-year-old Pablo Casals (later to become a world renowned cellist and conductor) stumbled upon the sheet music in a second-hand shop in Barcelona. The incident is described on the Vialma Classical Music site:

It was a normal day for the thirteen year old Pablo Casals. He was strolling with his father around Barcelona when, by chance, in a small second-hand shop, the young cellist found a music score that would mark a turning point in his life and career. Casals was already a musical talent. By the age of four he could play piano, violin and flute. At six he was already performing in public and when he reached eleven, he decided that the cello was the instrument for him and one that he would dedicate his life to.

The legend goes that Casals practiced the little known and rarely performed cello suites everyday for over ten years before finally playing them publicly in 1901. It appears that Casals followed the advice of the great composer who is quoted saying ‘I was obliged to be industrious. Whoever is equally industrious will succeed equally well.’ It appears that Casals’ work has paid off. As a result of his dedication, the cello suites now enjoy worldwide popularity and remain one of the most recorded and performed works for cello.

Although Casals performed the suites publicly, he would not begin recording them until he was 60, and then he was the first cellist to record all six suites between the years 1936-1939 at Abbey Road and in Paris for EMI. His pioneering complete set of the suites is still highly regarded, and I will discuss this more below in the recommended recordings.

Because no autographed or annotated copy of the scores survive, musicians and scholars have been trying to come up with a definitive performance edition for decades. But the discrepancies between versions in terms of articulation, slurs, bowing, dynamics, and rhythms has led to an extremely wide range of interpretations and opinions on how the suites should be played. Although there exists a secondary source of the manuscript, a handwritten copy by Bach’s second wife Anna Magdalena, it suffers from some of the same lack of indications. There is little to go on, but this is a blessing in a way as it allows for such a wide array of readings ranging from the romantic to intellectual, from exciting to eclectic, and from the historically informed to the traditional. What we know for certain is that the suites are similar to études (or studies) for the instrument, and that they are moderately to extremely demanding for the soloist. It has never been reliably established exactly when the suites were composed, or for that matter in which order they were composed.

There is also some dispute as to whether Bach intended the suites for cello as we know it today, and many scholars contend that the pieces were actually written for the violoncello (or viola) da spalla (the shoulder cello). But even this has never been firmly established, there are a few recordings on the market where the soloist uses the violoncello da spalla.

Most scholars believe Bach intended for the suites to be played as a cycle, such is the order he kept with the movements. The suites are in six movements each, and have the following structure and order of movements:

Prelude

Allemande

Courante

Sarabande

Galanteries: two minuets in each of Suite Nos. 1 and 2; two bourrées in each of Suite Nos. 3 and 4; two gavottes in each of Suite Nos. 5 and 6

Gigue

The Cello Suites have been transcribed for numerous and varied instruments, including virtually every stringed instrument along with the mandolin, marimba, piano, classical guitar, flute, horn, saxophone, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, trombone, euphonium, tuba, and ukulele, as well as being transcribed for orchestra.

Recommended Recordings

This is where I must admit to being less familiar with Bach’s Cello Suites than virtually any other work I have covered thus far. I would describe my feeling upon hearing the complete suites to be closer to admiration than love, and while I can certainly appreciate this music for the obvious genius it reflects, I have to be in a specific mood to spend a lot of time with it. Without a doubt there are many moments of transcendental beauty, but repeatedly listening to the suites is not enjoyable for me. Don’t get me wrong, I recognize this music as some of the most profound music ever written. But I need to take it in small doses.

Since Casals groundbreaking recordings in the 1930s, the Cello Suites have been recorded hundreds of times (over 400 times), and some high profile cellists have recorded them multiple times. They are among the most performed works for cello. Below I am including the recordings I am recommending based on the listening pleasure each brought to me, and I have not divided them into categories by style (i.e. romantic, historically informed, intellectual, etc.). I did not sample every recording of the suites available, but as always I am open to adding to my recommendations if I discover more recordings which bring me listening pleasure. If you don’t see your favorite recording below, send me a quick message and I will be sure to check it out.

Legendary Catalan cellist Pablo Casals’ complete set of the Cello Suites is a landmark in the history of classical music recordings. Recorded between 1936-1939 for EMI (now Warner), Casals’ playing is heartfelt and individual, a good reflection of Casals the man and musician. His beloved Spain was embroiled in a civil war when he went to London to record Suites no. 2 & 3, and a few years later he would record the remaining suites in Paris. The sound is mono, but due to some heroic remastering efforts, what we can hear today is in remarkably good sound given when the suites were recorded. Casals’ style will not appeal to every taste, as he was essentially an extroverted musician in the romantic style, and could sometimes be aggressive in his bowing. There are a few notes which are less than beautifully played. But if you are looking for playing of depth and profound expression, this is an absolute must.

French cellist Pierre Fournier was known as the “aristocrat of cellists” due to his majestic and refined tone and musicality. His recording of Bach’s Cello Suites from 1960-61 on the Archiv/Deutsche Grammophon label remains one of the most recommended versions ever recorded. Fournier creates a seamless musical line across each movement of the suites, something which just intuitively feels right. He is uncanny, taking phrases and building upon them. At times Fournier allows the cello to sing out, and it is true Fournier falls into the more romantic camp as far as interpretation. But tempos are in the mainstream, and Fournier has an innate sense of balance and control. Rhythms are perhaps a touch smoother than some more recent recordings, but still quite clear, and the utter charm and personality of this performance is delightful. If I were to choose just one recording of the complete suites to take to the desert island, this would probably be it.

French cellist Maurice Gendron also takes a more romantic view of Bach Cello Suites, similar to Fournier. Recorded in 1964 for Universal (Decca), Gendron’s performance is a model of refinement and tonal beauty. There are very few sharp edges here, and the smoothness and ease of Gendron’s style is what makes it so appealing. Are there versions that have more rhythmic bite? Yes. Are there versions that probe Bach’s variations in mood to a greater depth? Yes. But there is no doubt this is a rewarding set, with a full cello sound which is nicely balanced in the sound picture. Gendron uses more vibrato than almost anyone else on this list, even more than Maisky and Fournier, and some critics complain about his intonation being somewhat off. To be honest, I don’t notice that at all, but those with perfect pitch might notice it. I appreciate Gendron’s more assertive approach, and his fuller sound. But if you prefer a more historically informed approach, this is not the one for you.

The celebrated American cellist Yo-Yo Ma has recorded the Bach Cello Suites three times for CBS/Sony, in 1983, 1997, and in 2017. The interpretations are remarkably similar and consistent, and all three recordings have been generally acclaimed. While the 1997 recording uses a lower pitch than the other two, and has marginally fuller sound, what you get with Ma is pretty much the same across the board. While Ma uses a modern instrument with modern strings, his style is less romantic than you will hear with Fournier, Maisky, or Weilerstein. While tempos are never too swift, Ma is more focused on rhythms and the dance. He also avoids too much vibrato, even while his phrasing is a bit romantic in spots. The 1983 recording finds a young Ma technically superb, while the latter two recordings contain more depth and maturity in terms of interpretation. I quite like the 1997 version in terms of spark and a slightly deeper intonation in the cello. The 2017 recording finds Ma slightly more relaxed and at home with the suites, perhaps a bit more inward, but he still plays the dances extraordinarily well. Again, the readings are quite similar. That goes for the sound quality too, though the most recent recording may have a slight edge there. Ma’s cello itself is not my favorite sounding cello, I find it somewhat nasal and astringent sounding, with more of a pinched quality than many others. This doesn’t affect my enjoyment of the performances, and is more of a personal preference.

The larger than life Latvian-Israeli cellist Mischa Maisky has recorded the Bach Cello Suites twice on audio, and once more for DVD. My recommendation is for his first recording from 1985 on Deutsche Grammophon. Maisky is firmly in the romantic category here, and he produces a beautiful, full tone. Tempos are mainstream, leaning to the slower side, which I certainly don’t mind. Maisky shades the dynamics nicely, and his phrasing is assertive and very expressive, even more so than Casals and Fournier. This is miles away from being historically informed, but it is highly enjoyable, sumptuous cello playing. The sound has a digital sheen on it, similar to many recordings from the 1980s, but nothing bothersome. The cello sound is rather close and focused. Maisky has been quoted as saying “Bach was the greatest romantic”, which is a problematic statement but certainly consistent with his interpretation. I think other interpretations may shed more light on Bach, but if you just enjoy this for what it is, it is well worth it.

The great Hungarian-American cellist János Starker recorded Bach’s Cello Suites at least five times, but it is his final one, the 1992 recording on RCA Red Seal (Sony) that is my favorite. This is a mainstream, and yet exciting account which finds Starker at a place in his career where he could bring a lot of experience and vision to the interpretation. Starker’s Mercury recording from 1963 is also highly regarded and more technically proficient, but I prefer this one for the far better sound quality and because Starker allows the music to breathe. It is a more considered reading, and Starker doesn’t rush through anything. Somewhat similar to Fournier, one of Starker’s great strengths in this set is his approach to simply let the phrases flow out of one another. There are very few moments of incisive articulation, but I would not call it a romantic reading or overly indulgent in the style of Maisky or Gendron. Starker is very keen on varying the dynamics, sometimes in traditional ways, sometimes in new ways. I noticed that the lower register notes, and the deeper guttural notes are especially well done on this recording. Starker won a Grammy Award in 1997 for the album (it had not been released for five years after it was recorded).

The Dutch cellist Pieter Wispelwey recorded the Bach Cello Suites three times, in 1989 and again in 1998 for Channel Classics, and then in 2012 for Evil Penguin. I am recommending both his 1989 and his 1998 recordings on Channel Classics, where Wispelwey uses a Baroque cello and a violoncello piccolo in Suite no. 6 on both recordings. I am not completely enamored of the Baroque cello, at times it sounds rather meager compared to the fuller sounding modern cello. But especially in Bach, the Baroque cello can create colors and feelings which are not possible on the modern instrument. Such is the case in these wonderful recordings from Wispelwey. There is a lightness and freshness to the sound, and the cello is not as closely miked as some others. Wispelwey is a bit more extroverted in the earlier recording but he always makes the most of each phrase, and rhythms are sprightly in both and the resonant acoustic for both recordings means that you can hear the notes just float into the air. The cello in this recording helps clarity the upper register, while the lower register is not as heavy. In general tempos are quicker, consistent with the historically informed approach. Occasionally this leads to some loss of detail, but nothing troubling. Wispelwey is never too assertive, so while these are relaxing and insightful readings, if you are looking for excitement you may want to look elsewhere.

Yet another French cellist, this time Ophélie Gaillard, has recorded Bach’s Cello Suites twice, in 2001 on the Ambroisie label and again in 2011 for the Aparte label. Both are quite good, but it is the earlier recording that I am recommending here. Gaillard was only 27 at the time of the recording, but this is playing of great distinction and insight. It is unclear if Gaillard is using a Baroque cello on this recording (most likely it is, we are told it is from the 18th century), though she does use a Baroque bow and the strings may in fact be gut strings. Either way, the cello is captured marvelously in all registers, and it has a very pleasing resonance and depth. Gaillard uses a violoncello piccolo in Suite no. 6, typical of Baroque artists, and it sounds wonderful. Gaillard’s playing throws off sparks and she is not afraid to dig into the bass notes. She is expressive and exciting in equal measure, and I found myself constantly enjoying her more extroverted style. The sound is near ideal for the cello, fairly up close but well balanced. Her second recording from 2011 shares many of the same qualities, though it is perhaps slightly more laid back.

The Lithuanian cellist and conductor David Geringas was unknown to me before this survey, but he studied under Rostropovich in Moscow in the 1960s, and he has had a successful career as a cellist and conductor. The recommended recording is a 2011 release on the ES-DUR label, but the performances may actually be from as far back as 2000. It is available on streaming services. First, the sound quality is excellent, clear and spacious but also detailed. Geringas produces a gorgeous and full tone, but also employs a crisp attack and rhythmic vibrancy. Tempos are moderate, never too fast nor too slow, dynamics are judiciously chosen, and the phrasing feels spot on. To my amateur ears, Geringas sounds like an absolute master in terms of intonation, nobility, and dance sensibility. His playing has such an appeal and character to it, but also excitement. The cello has a modern sound, but Geringas uses vibrato relatively sparingly and plays briskly when called for. A joy to hear.

Russian cellist Alexander Rudin recorded the Bach Cello Suites for the Naxos label in 2000 (released in 2002), and overall it is one of the most recommendable versions. Rudin has tried to be historically accurate in his performance, though to my ears it sounds like a modern cello without gut strings. In Suite no. 6, Rudin uses a contemporary five string cello. In terms of phrasing, the relative lack of vibrato, and the clarity of textures, Rudin certainly follows more historically informed practice. His cello sounds superb up and down the register, with a quality of sound which is rich yet crisp and detailed. There is virtually no harshness in Rudin’s sound, and he is adept at using both legato and staccato when needed. In fact, the faster passages are some of the most fun with Rudin able to not just play the notes quickly but he also puts his own personality into the phrases. The sound is top notch from Naxos.

The French-Québécois cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras is without a doubt one of the top cellists in the world today, and has now recorded Bach’s Cello Suites twice, in 2007 for harmonia mundi and again in 2023 also for harmonia mundi. I am recommending both recordings here. In the 2007 recording, Queyras displays a natural and appealingly eloquent sound, and his virtuosity is matched by his musical understanding. The faster dance episodes have spring and panache, the Allemandes are thoughtful and never rushed, and the Preludes have an appropriate nobility. The reverberant acoustic has a bit too much echo, but overall the sound has nice presence. The more recent 2023 recording (released in 2024) brings even more revelations, as Queyras is even more refined but also more spontaneous sounding. He uses ornamentation in some places, and there is more confidence in his playing, and his sound is more focused and vivid than in 2007. He plays a very old cello with modern strings and bow, but acknowledges historically informed practice in his very selective use of vibrato as well as his prioritization of the dance rhythms and his sparing use of legato. I particularly enjoy the flexible tempos and dynamics which Queyras uses on this second recording, certainly in keeping with the freedom this score seems to offer. There is less reverberation on the more recent version. You can’t go wrong with either recording.

The 2006 recording by the Israeli cellist Gavriel Lipkind (unknown to me until one of my readers recommended him to me) on Lipkind Productions is a one of a kind experience. I mean that in the best possible way. This is a very individual recording, full of personal touches. Lipkind is by turns emotive, probing, supple, reflective, dashing, inward, and demonstrative depending on the movement and the mood. This is a special recording, but certainly shouldn’t be a reference choice because it is probably too far off the beaten path. But what a path Lipkind trods! The sound from his cello is dark, deep, and brooding but Lipkind’s articulation is clear and precise. The acoustic is a touch too reverberant for my tastes, but that is a small thing. Overall, if you are looking for a recording that is unique and really has something new to say, this is it.

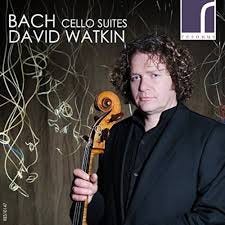

The period cellist David Watkin from the U.K. recorded a wonderful set of the Bach Cello Suites in 2013 for the Resonus label, and if you are looking for a recording on a Baroque cello (with a piccolo cello on Suite no. 6), you should investigate this one. Watkin not only uses a Baroque cello, but also a Baroque bow and gut strings. You will immediately notice the differences in pitch and overall sound. There is quite a bit of air around the notes, and Watkin produces a relatively light and airy sound as well. The tone is thinner than you will hear with a modern cello, but the bass notes certainly emit quite an earthy growl. Watkin has clearly thought through the suites a great deal, and he has much worthwhile to say in this music. Tempos are brisk, but Watkin also gives plenty of space for the slower movements, and he provides a lot of differentiation in moods between movements. There are too many highlights to list here, but suffice to say Watkin enhances the listening experience by making the suites sound fresh. He produces some unique colors on his cello, and his choice of emphases on phrases and dynamics is interesting and exciting.

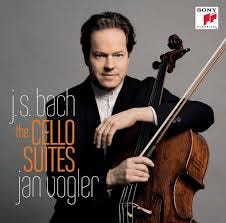

Also from 2013 is a lovely set from the German cellist Jan Vogler on Sony Classical. This is recommendable on the basis of the outstanding sound quality, but also because Vogler essentially plays without much of an ego here, and presents Bach as he believes the composer would want. But that is not to say Vogler is boring, indeed there are many moments of dynamic shading, leaning into phrases, and variations of tempo. But Vogler isn’t creating anything new here, but rather just revealing what the music has to say. The performance has a natural ebb and flow which feels genuine, and there are no tricks or eccentricities. I can see how this would be an ideal set for someone first coming to this music, there is a rightness about the recording. The cello is perfectly balanced in the sound picture, and Vogler is neither overly romantic nor too literal. The sound he creates is also admirable, rich and resonant but with plenty of agility.

German-Korean cellist Isang Enders recorded the Bach Cello Suites in 2012 and 2013 for the Berlin Classics label, and it has to be one of my very favorite recordings available of this music. Only 24 at the time, Enders makes this music come alive in a way I’ve rarely heard. Tempos are some of the fastest among recommended versions in some of the dances, but then Enders also slows things way down at other points such as in the Allemandes. The musical line is rarely lost and Enders has an intuitive sense of phrasing which is a delight. Enders focuses a lot on how he wants to express phrases as well as the dynamics, and occasionally he will lose sight of the big picture. But he always finds his way back, and in terms of the journey itself, no other recording is quite as interesting. Enders’ recording brings to mind Ma’s fine recordings, though Enders is more emotive and less intellectual. The sound is ethereal and airy, with the cello at a fairly central point in the sound picture.

The young French cellist Bruno Philippe (yet another French cellist!) recorded Bach’s Cellos Suites in 2020-2021 for harmonia mundi using a Baroque cello and a Baroque bow. This is a captivating and stimulating set of the suites, with the cello recorded closely and with Philippe delivering a fiery and thought provoking performance. Just listen to the Courante from Suite no. 1…wow. This is stunning playing, and totally unique from any other recording I’ve heard. I remain amazed at how Philippe has chosen to characterize each dance as if each had its own distinct personality. Dynamics are more extreme on both ends of the spectrum than we hear normally, and the smoothness of Philippe’s bowing is something special. You get the feeling that Philippe is creating a story with each movement, and while that might create less continuation from one movement to the next, it certainly makes each individual movement a new discovery. Philippe plays with polish, but it feels so spontaneous and fresh. He includes some ornamentation too, which personally I found completely appropriate and thrilling. The rusticity in Philippe’s tone only adds to the enjoyment for me, and the way he plays with abandon in the Gigues and Courantes is terrific. A completely enjoyable recording by every measure.

Honorable Mention

Since I feel a considerable lack of confidence in my recommendations this time, I urge you to check out the recordings below if you like this music. Many of them are very fine, and you may prefer one or more to those I’ve listed above.

Paul Tortelier (EMI/Warner 1961)

Anner Bylsma (Sony 1977)

Andre Navarra (Caliope 1978)

Paul Tortelier (HMV 1983)

Heinrich Schiff (Warner 1985)

Mari Fujiwara (Denon 1985)

Mistislav Rostropovich (EMI/Warner 1995)

Jaap Ter Linden (Harmonia Mundi 1997)

Catalin Ilea (One World Music 2001)

Truls Mørk (Virgin 2005)

Tim Hugh (LSO Live 2005)

Steven Isserlis (Hyperion 2007)

Antonio Meneses (Rambling 2007)

Anne Gastinel (Naïve 2007)

Richard Tunnicliffe (Linn 2012)

Nina Kotova (Warner 2014)

Thomas Demenga (ECM 2017)

Alban Gerhardt (Hyperion 2018)

Alisa Weilerstein (Pentatone 2019)

Benedict Kloeckner (Brilliant 2020)

Karel Steylaerts (etcetera 2022)

Petr Skalka (Claves 2024)

Join me next time when entry #75 on our survey lands on Beethoven’s wonderful Cello Sonatas 1-5 and Variations. See you then!

_____________

Notes:

Agam, Tal. Review: Bach – 6 Cello Suites – Yo-Yo Ma (2018). Online at theclassicreview.com. August 25, 2018.

Badiarov, Dmitry. "J.S. Bach – Violoncello da Spalla Suites". The Violin Blog of Dmitry Badiarov – violin-maker. 29 August 2010.

Dalkin, Gary S. "J.S. Bach: Cello Suites. Heinrich Schiff. EMI Double Fforte CZS 5741792". MusicWeb International. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

de Acha, Rafael. "Review: Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750): Six suites for unaccompanied cello, Carmine Miranda (cello), CENTAUR CRC3263/4". MusicWeb International. 2012.

Finckh, Eckhard. "Kritischer Blick auf Cello-Suiten" (in German). Nürtinger Zeitung [de]. 8 May 2013. (subscription required).

Rutherford, David. "The Story Behind the Bach Cello Suites, And Why We Still Love Them Today". Colorado Public Radio. Retrieved 2022-06-21.

Sevier, Zay David (1981). "Bach's Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas: The First Century and a Half, Part 1". Bach. 12 (2): 11–19. ISSN 0005-3600. JSTOR 41640128.

Stowell, Robin. A revisiting of a classic brings rewards aplenty. Online at https://www.thestrad.com/reviews/jean-guihen-queyras-bach/18786.article. December 2024.

Wittstruck, Anna. "Dancing with J.S. Bach and a Cello – Introduction" Archived 2013-03-25 at the Wayback Machine. Stanford University. Stanford.edu. 2012.

https://bachcellosuites.co.uk/

https://www.vialma.com/en/articles/72/Casals-and-the-Bach-Cello-Suites

Great survey, as usually. I’m really surprised I can’t find Henrich Schiff, One of the best in my opinion. But my favorite version is Gavriel Lipkind on Edel Classic, a rare gem I discovered a couple of years ago.

Dear John, thank you for this post. I enjoy your in depth analyses on the most beautiful classical recordings very much! With regard to this post on the Cello Suites by Bach, I suggest a correction: Pieter Wispelwey is still alive and active as a musician. The post mentions "the late...". It was his son who died in a tragic accident a couple of years ago. And his name is also misspelled as "Wispelway". Best regards, Lourens Visser.