Building a Collection #73

Piano Concerto no. 1 in B♭ minor, Op. 23

By Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

________________

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born in 1840 in Votkinsk, Vlatka District, Russia and died in 1893 in St. Petersburg, Russia. Tchaikovsky was the composer of some of the most popular and enduring melodies and themes in classical music and is widely considered to be the greatest Russian composer ever. Although he lived through a time of tremendous change in musical styles, at heart he was a Romantic and his music is relatively traditional and conservative in style. He is not considered an innovator, but such was his musical genius that his appeal and communicative power lies with his ability to sweep us up in his melodic charm and depth of feeling. Tchaikovsky’s music spanned ballet, symphonic, orchestral, concerto, opera, vocal, chamber music, keyboard, and choral genres. The works that have generally garnered the most acclaim are his ballets, symphonies, orchestral works, and concertos.

Pyotr Ilyich began taking piano lessons at age four, and immediately showed tremendous talent. By the age of nine, however, his anxiety was so great that it significantly impeded his ability to play. Tchaikovsky was a sensitive young man by nature, and the loss of his mother when he was 14 was a crushing blow. While he pursued a legal career for a time, he was continually drawn back to music. In 1861 he began studying composition and harmony and enrolled at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Eventually he would study with the composer Anton Rubinstein.

In 1866, Tchaikovsky moved to Moscow to take up a teaching position at the new conservatory there. Shortly after taking the post he composed his Symphony no. 1, but suffered a sort of nervous breakdown while composing it. Other early works appeared, the most notable being the ballet Swan Lake in 1875. During travels to Paris and Bayreuth, Tchaikovsky met Liszt, but was allegedly snubbed by Wagner. Swan Lake premiered in 1877, leading to greater notoriety and fame. During 1877-1878 Tchaikovsky also composed his Symphony no. 4, which was his first big symphonic breakthrough. He would go on to compose several other blockbuster classical works such as The Nutcracker, Sleeping Beauty, Piano Concerto no. 1, Symphony no. 5 and Symphony no. 6 “Pathetique” and the Serenade for Strings.

It was also around the same time Tchaikovsky made the foolish decision to marry an admirer by the name of Antonina Ivanovna Milyukova. Most biographers and musicologists agree that Tchaikovsky was homosexual, so the marriage was certainly not a match. But neither was it happy in other ways, and after only a few short months the marriage ended. It was deeply humiliating for Tchaikovsky and led to a suicide attempt. Throughout the debacle, Tchaikovsky’s family remained supportive of him. It may have been the case that the failed marriage forced him to face his sexuality. In any case, he never blamed Antonina for the failure. Throughout the ordeal he continued to correspond with and confide in a woman who was his largest benefactor and pen-pal, Nadezhda von Meck.

Over the years Tchaikovsky’s personal life has been the subject of intense debate and scrutiny, much of it concerning his sexuality. The stance of the Soviet censors was to portray him as heterosexual, and to get rid of any reference to his same-sex attractions. Such censorship has even continued into recent Russian propaganda. But it is well-established that Tchaikovsky sought out the company of men consistently, and that he was deeply in love with a man named Sergey Kireyev, a fellow jurisprudence student while in school. There is little doubt Tchaikovsky had strong same-sex feelings, as this can be found in his brother’s autobiography, as well as Tchaikovsky’s own letters that escaped the Soviet censors.

What is less clear is how impactful the realization of his homosexuality was in Tchaikovsky’s life. David Brown, noted musicologist and biographer, says that he "felt tainted within himself, defiled by something from which he finally realized he could never escape". But Russian-American scholar Alexander Poznansky maintains that Tchaikovsky experienced little guilt over his sexual desires and "eventually came to see his sexual peculiarities as an insurmountable and even natural part of his personality ... without experiencing any serious psychological damage." The role that his sexuality played in his life and his music has recently been downplayed by many scholars.

In terms of Tchaikovsky’s legacy as a composer, it is fair to say he forged his own path by combining elements from German symphonic tradition, Russian folk songs and patriotic music, as well as his uncanny ability for melodic invention. He accomplished this while having very little in the way of a Russian musical tradition to call upon for inspiration. Tchaikovsky wanted to be true to his national roots, while at the same time creating art which would be fully embraced in Europe and the west. He was successful in doing this, perhaps more than any other Russian composer. Certainly he was also important to other Russian composers that would follow such as Stravinsky, Shostakovich, and Prokofiev.

For me Tchaikovsky’s music will always have a beauty, charm, immediacy, and emotional power which never goes out of style. The expressiveness of his musical language reflects the human condition in a way that few others have matched.

Piano Concerto no. 1

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto no. 1 was completed in February 1875, but he would revise it two more times in 1879 and again in 1888, the last revised version being the primary one heard today. Tchaikovsky originally wanted his good friend and pianist Nikolai Rubinstein to premiere the work, but Rubinstein refused to perform it and criticized the work in brutal terms in what turned out to be one of the more notorious interactions of Tchaikovsky’s career. Tchaikovsky recalls Rubinstein’s feelings on first hearing it:

“It turned out that my concerto was worthless and unplayable; passages were so fragmented, so clumsy, so badly written that they were beyond rescue; the work itself was bad, vulgar; in places I had stolen from other composers; only two or three pages were worth preserving; the rest must be thrown away or completely rewritten…I was not only astounded but outraged by the whole scene. I am no longer a boy trying his hand at composition, and I no longer need lessons from anyone, especially when they are delivered so harshly…I need and shall always need friendly criticism, but there was nothing resembling friendly criticism. It was indiscriminate, determined censure, delivered in such a way as to wound me to the quick. I left the room without a word and went upstairs. In my agitation and rage I could not say a thing. Presently Rubinstein enjoined me, and seeing how upset I was he asked me into one of the distant rooms. There he repeated that my concerto was impossible, pointed out many places where it would have to be completely revised, and said that if within a limited time I reworked the concerto according to his demands, then he would do me the honor of playing my thing at his concert. "I shall not alter a single note," I answered, "I shall publish the work exactly as it is!" This I did.”

As biographer John Warrack noted, Rubinstein thought the solo part was too difficult and that some of the solo sections that are hidden underneath the orchestra were unnecessarily fiendish for even the best virtuoso to play. But he also thought the music itself was uneven in its inspiration, and at first he admitted to not understanding much of it. Interestingly, Rubinstein eventually came around to championing the concerto and indeed becoming one of its greatest advocates. He first performed it himself in 1878 in Moscow.

Because Rubinstein refused to premiere the work, the first performance was actually given in Boston on October 25, 1875 with Hans von Bülow on piano with a freelance orchestra under Benjamin Johnson Lang. Bülow was an admirer of Tchaikovsky’s music, and the reason it was premiered so far away was because Bülow was about to embark on a tour in America. Since we know Tchaikovsky was deeply insecure about his work and that Rubinstein’s comments had likely wounded him, it may have been enticing to him for the concerto to be premiered far from home to avoid any humiliation if the performance did not go well. As it happened, the concerto was a big hit at the first performance, the audience even demanding that the Finale be repeated! Many more performances were soon scheduled. Bülow himself called the work "original and noble".

The critics were not so generous. One said the work was “hardly destined to become a classic”. Another one pointed out that the trombones had entered at the wrong place in the performance, prompting Bülow to audibly yell “The brass may go to hell". The next performance in New York was better performance wise. Thereafter the work was premiered in Saint Petersburg and Moscow in November 1875, with Tchaikovsky being especially moved and gratified by the Moscow performance with Rubinstein conducting (the same Rubinstein that had derided the work earlier) and Sergei Taneyev on piano. Tchaikovsky praised Taneyev’s wonderful rendition.

The concerto follows a traditional three-movement structure as follows:

Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso – Allegro con spirito

Andantino semplice – Prestissimo – Tempo I

Allegro con fuoco – Molto meno mosso – Allegro vivo

The opening part of the concerto is among the most well known openings in classical music, with the short horn theme followed by sharp orchestral chords leading to a glorious piano statement. But rather surprisingly, this memorable opening theme never returns! Therefore, it may be the case that many folks are familiar with this famous beginning, but may have never listened to the rest of the movement or the rest of the concerto. That is a pity, but in some ways one can understand Rubinstein’s initial reaction to hearing it, particularly the first movement. The first movement is overly long in my opinion, and not especially cohesive. But according to Russian music scholar Francis Maes, Tchaikovsky knows exactly what he is doing. Maes comments:

“For a long time, the introduction posed an enigma to analysts and critics alike…The key to the link between the introduction and what follows is ... Tchaikovsky's gift of hiding motivic connections behind what appears to be a flash of melodic inspiration. The opening melody comprises the most important motivic core elements for the entire work, something that is not immediately obvious, owing to its lyric quality. However, a closer analysis shows that the themes of the three movements are subtly linked. Tchaikovsky presents his structural material in a spontaneous, lyrical manner, yet with a high degree of planning and calculation.”

Maes contends that all the themes have a motivic commonality. These themes include the Ukrainian folk song "Oi, kriache, kriache, ta y chornenkyi voron ..." as the first theme of the first movement proper; the French chansonette "Il faut s'amuser, danser et rire" ("One must have fun, dance and laugh") in the middle section of the second movement; and a Ukrainian vesnianka "Vyidy, vyidy, Ivanku" or greeting to spring which appears as the first theme of the finale. The second theme of the finale is derived from the Russian folk song "Poydu, poydu vo Tsar-Gorod" ("I'm Coming to the Capital") and also shares this motivic bond. The relationship between them has often been ascribed to chance because they were all well-known songs at the time Tchaikovsky composed the concerto. But it seems likely that he used these songs precisely because of their motivic connection. Maes writes, "Selecting folkloristic material went hand in hand with planning the large-scale structure of the work."

The second and third movements are considerably shorter. The second movement Andantino semplice is charming and lush with the piano collaborating back and forth with the orchestra. The Finale is in the form of a rondo, and it is a rollicking good time with the piano taking on an extrovert virtuosic role. The final descent and then ascent by the piano comprises one of the most thrilling finishes in the concerto repertoire.

The Essential Recording

There are loads of recordings of Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto no. 1, perhaps too many. It fits the definition of a “war horse” work, which has been performed repeatedly. If I’m being honest, listening to dozens and dozens of recordings of the work has led me to conclude that it is rare when a pianist has something new to say. There are a handful of exceptional performances followed by many, many routine accounts. Some readings put forth a more romantic approach, while others are more straightforward in underlining a more classical approach (after all, Tchaikovsky was a great admirer of Mozart).

There is one recording that arguably stands head and shoulders above the rest, and that is the 1993 recording by pianist Martha Argerich and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra led by Claudio Abbado, recorded live by Deutsche Grammophon. Regular readers know very well the high regard I have for Argerich, and the Tchaikovsky 1 is a work she has recorded commercially three times, and there are several more unofficial live recordings. But the Berlin recording is special. Such is the nature of the performance it almost feels as though Tchaikovsky wrote the concerto especially for Argerich. She plays the notes clearly, and in faster passages she actually plays all the notes, which is a task in itself. But Argerich never falls into the trap of over sentimentalizing the phrases, instead choosing to continue moving forward with a more classical pulse. Some critics have said this performance is too fast, but I disagree.

Argerich engages the listener with a wide range of dynamic choices, always matching Abbado and the orchestra. As always with Argerich, her hands are equals and we can hear all the voices of the piano well. At times Argerich is criticized for plowing ahead too fiercely and for glossing over some of the nuance. But not here. Just listen from about 5’00” to 9’00” in the first movement, there is an amazing amount of subtlety and a refined touch shown here. Argerich masters all the moods present, and for me no other performance brings out so many colors. But still no schmaltz, and that is important. This concerto can so easily get bogged down in the first movement, and Argerich and Abbado refuse to let that happen. Yet, they are ideal at building the tension…listen again at 11’30” where the buildup is handled so well. Underneath the orchestra in this section Argerich can be heard playing all the fiendish, almost unnecessary runs delicately but also thoroughly and accurately. The passages which require the pianist to play several octave runs consecutively hold no terrors for Argerich.

The central section from the second movement Andantino is projected with the utmost virtuosity and yet clarity is maintained. It dances with such beauty and vividness, and the Berlin woodwinds and strings are impressive. The pulsating yet lyrical nature of the movement is captured marvelously. The Finale is edge of the seat excitement, bouncing off the page like the musicians are possessed. Even in the faster passages, Argerich is able to shade the dynamics. The first big entrance of the orchestra in the Finale sounds fantastic, and all the way along we are reminded of just how gifted Abbado was as an accompanist (and just listen to how clear the brass are here!). This is nothing short of thrilling music making. Argerich is at her best, and so are Abbado and the BPO.

I should make a special mention of how good the Berlin Philharmonic sounds on this recording, and just how much I admire Abbado’s direction. This is great stuff. At times Abbado could be too cautious as a conductor, but here the orchestra is responsive and engaging throughout, and the sound from the Philharmonie in Berlin is well above average from a notoriously difficult recording venue. The engineering from Deutsche Grammophon is excellent in my view. Spectacular.

Recommended Recordings

Vladimir Horowitz also could have made a career from his many performances of this concerto alone, such was his technical prowess. But for me the live 1943 recording from Carnegie Hall with the legendary Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra takes the prize. The sound is dated as you might imagine, but perfectly serviceable for being 82 years old! Somewhat like Argerich, Horowitz is not one to linger or use too much rubato. There is a refreshing directness to the reading, perhaps because this was Toscanini’s style as well. Horowitz’s virtuosity is on display, and he tended to show off his chops wherever he could. But there is also a beguiling tenderness in softer passages, showing that he wasn’t always the showman. The Andantino is one of the quickest on record, but it doesn’t feel too fast in my opinion. The Finale is not the headlong sprint of Argerich above, but is impressive nonetheless, nicely sprung and well articulated. The orchestra sounds boxy to be sure, but you can still hear all the details.

The 1955 partnership with Soviet pianist Emil Gilels and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under legendary conductor Fritz Reiner produced one of the great accounts of this concerto for RCA Living Stereo. The sound from Orchestra Hall in Chicago is good (but not great) for its vintage, even if a few edits can be audibly heard (I should mention the 2020 version on the Profil label sounds better to me, perhaps remastered). Gilels also recorded the concerto several other times, but for me this is the best. His live 1980 account from New York with Mehta is also worth hearing, though it is not quite on the level of this one. Gilels was a great artist, but could sometimes plod through notes without much characterization. But here he plays with sensitivity and bravura, taking us on a fun ride. The performance has a certain authority to it, and the listener wants to keep listening to hear what is coming next. The dramatic impulse is palpable, as is the artistry of Reiner and Gilels.

I maintain a strong recommendation for Van Cliburn’s recording of the concerto with Soviet conductor Kirill Kondrashin and the RCA Symphony Orchestra on RCA Living Stereo from 1958. Famously this recording was made in the wake of Cliburn’s historic win at the 1958 International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow at the height of the Cold War. We know Cliburn came home to ticker tape parades and to a celebrity reception, but this studio recording made after his triumph was the first classical album to sell over a million copies. Many record enthusiasts claim this recording is not nearly as good as Cliburn’s actual winning performance of the same concerto, with the Moscow Philharmonic (also under Kondrashin). Recordings of the winning performance are available, most notably on the Testament label, but judge for yourself. It is my firm opinion that the later studio recording is the better performance, and certainly is in better sound. If you like your Tchaikovsky big and lyrical, this is the recording for you. Cliburn possessed a tremendous gift for lyricism, and while there is still plenty of power here, where he stands out is in the more expressive and melodic sections. The sound is marginally better than on the Gilels/Reiner recording, and if the performance is a bit less exciting, it sounds more natural and plumbs some of the emotional depth to a greater degree. Kondrashin was always a very underrated conductor, and here he shines with the RCA band (which at the time was mostly composed of New York Philharmonic musicians). This remains a truly great recording.

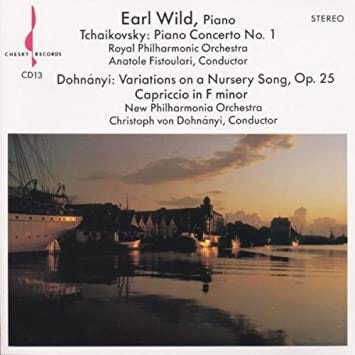

One of my readers named Michael pointed out a glaring omission from my original list of recommendations, that being the 1962 recording featuring the American pianist Earl Wild. Wild is joined by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under conductor Anatole Fistoulari in a recording that has appeared on various labels over the years including RCA, Chesky, and Reader’s Digest. I am extremely grateful to Michael for pointing out this recording for it is one of the great recorded versions of this concerto. Wild’s playing is refined but also contains a good portion of fire and excitement. What I especially like about Wild and Fistoulari is the way they vary the dynamics and tempo even within the same movement. In the first movement, there is a moderate acceleration and push forward at 7’42”, then again at 10’25”, and then again at 12’00”. In the Finale, speed is not the goal but rather musicality and articulation. It is a joy. Listen to how Wild shapes the phrases at 1’05” and again 1’20”. The acceleration in the Finale beginning at 5’45” is thrilling. In the first two movements, Wild produces some of the most beguiling and sophisticated piano sound I have heard. Fistoulari was certainly an underrated conductor, and his Tchaikovsky albums in particular are prized. He conducts an RPO that sounds alive and on top of their game, with the brass especially pungent and the strings vibrant. A small note on the sound, the orchestral part is harsh in spots and Wild’s piano sounds almost muted at times. The recording balance is not ideal. But in no way should this diminish your enjoyment of this classic recording. The availability is a bit spotty, I could not find it on idagio, and I found it on Spotify only after digging quite a while. But I noticed it is easily found on Amazon music.

The Brazilian pianist Nelson Freire’s genius was somewhat underappreciated in my view. His recording of the Tchaikovsky 1 from 1969 on CBS/Columbia (Sony) with Rudolf Kempe and the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra is scintillating, and is easily recommended. The sound is a bit fierce and the piano is placed very forward relative to the orchestra, but I find this appropriate for a larger than life piece such as this. In some of the louder passages, Freire is less than subtle but he makes up for it in other ways. I’m not sure Kempe would be my first choice for a Tchaikovsky conductor, but he leads the Munich orchestra quite well here. I like the tempos adopted throughout, and there is a quality of electricity and energy I enjoy. Freire’s tone is full and the notes are clear and pointed. Even though Freire was one of the finest romantic pianists of his era, this reading to me echoes Argerich and Horowitz in terms of offering a more direct take on the concerto. The Andantino finds Freire bringing out a more lyrical, romantic tone. The Finale is thrilling and satisfying.

As I mentioned above, there are several live recordings of Martha Argerich playing the concerto on smaller labels. One especially good one is her live 1979 recording with the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Kazimierz Kord on the CD Accord label, available on streaming services as well. The piano is placed quite forward, while the orchestra is a bit too recessed in the sound. This performance compares well to the DG recording with Abbado, even if the Warsaw orchestra is not captured as well as the Berliners. Argerich’s approach is similarly direct, with a terrific forward impetus, and if anything is a bit more spontaneous than in Berlin. Argerich’s trademark emotional involvement is present too, but once again she blows the dust off the work’s tired reputation. She is able to rescue the concerto’s inherent nobility, while also maintaining an essentially passionate approach.

I don’t wish to court controversy by including Ivo Pogorelich’s 1986 recording on Deutsche Grammophon, but it seems he divides opinions more than most pianists. On the recording Pogorelich is joined by the London Symphony Orchestra and Claudio Abbado. Say what you want about Pogorelich’s unconventional performance, but it isn’t boring and contains several details and insights you won’t find elsewhere. Pogorelich is spontaneous, while Abbado’s contribution tends to balance him out in the mix. The sound is not as immediate as with Argerich/Abbado, but has plenty of warmth and detail. Pogorelich emerges as a true artist, a thoughtful musician, and someone willing to take some risks. He places emphasis in specific places, and his phrasing is different than we are used to hearing. I don’t mean to imply that this reading is far outside the mainstream, because I don’t believe it is. But small differences in how he plays the notes add up to a significant difference in perception. Pogorelich is perhaps best in the more subtle passages where he truly takes his time and disarms the listener with playing of tenderness and beauty. This makes the first movement Allegro non troppo one of the slowest on record, but it is the opposite of boring (take his treatment at about 9’00” as a sample). The Andantino is also taken slower, but it also comes out the better for it with Pogorelich’s approach. He bounces the notes when so inspired, but at other times employs a more legato sound. The Finale finds Pogorelich doing the same sort of thing where he swells the phrases, then backs off, creating an undulating sort of feeling. This is more measured than Argerich, but the upper and lower registers can be heard even better and Pogorelich’s tone is especially sparkling in this last movement. Kudos again to Abbado for following Pogorelich’s vision for the work.

The 1993 Hyperion recording by pianist Nikolai Demidenko and the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Alexander Lazarev is a real sleeper recommendation, but deserves much more attention. Demidenko is thoughtful and original in the first movement (almost reminds me of Pogorelich). His technique is clear and persuasive, and he brings plenty of power to bear on the proceedings, and is given strong and well-played accompaniment by Lazarev and the BBC musicians. The long first movement is the hardest to get right in my opinion, and here Demidenko and Lazarev shape each section into something that makes sense within the whole (listen to the horns cry out at 16’10”!). The Andantino is deliberate, but admirably so because Demidenko treats every phrase as precious. The Finale is not rushed nor overstated, but builds to a frenzied crescendo and a most satisfying conclusion.

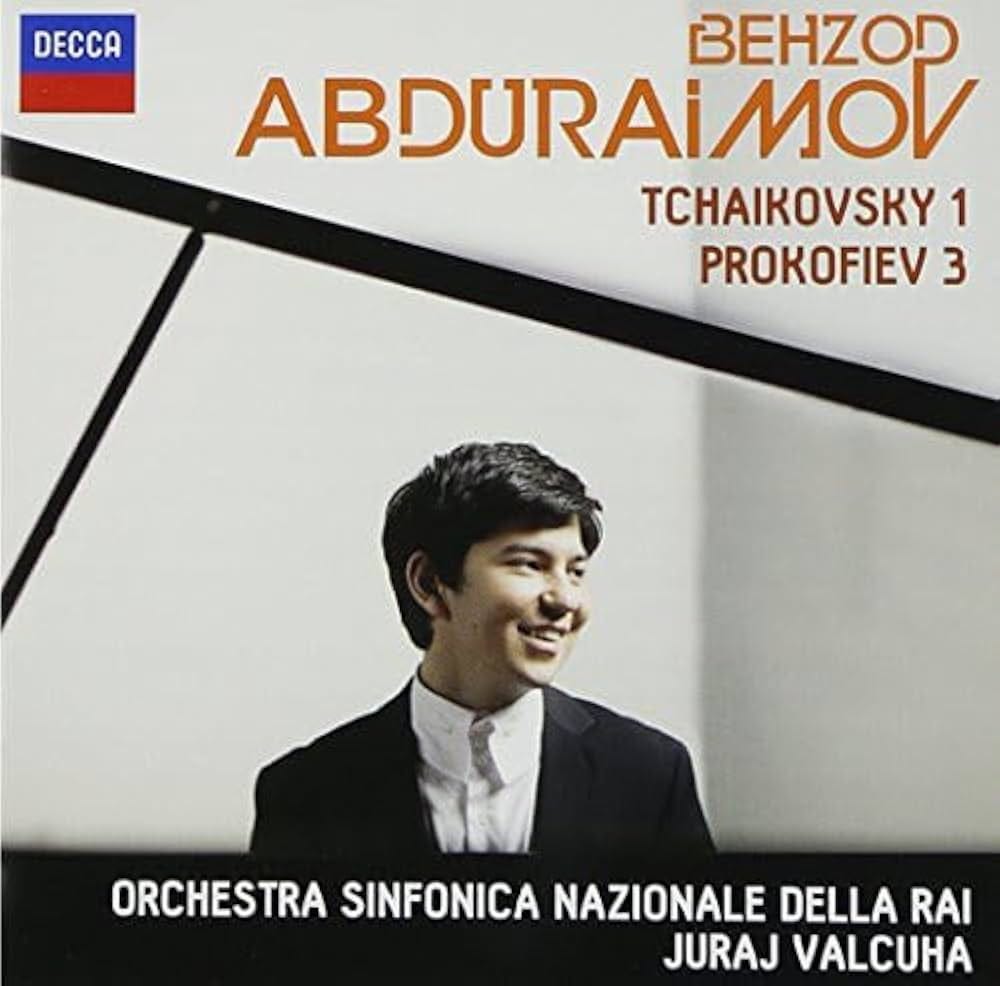

The 2014 recording featuring the young Uzbek pianist Behzod Abduraimov with the Italian orchestra, the Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI of Turin, Italy and conductor Juraj Valcuha on the Decca label is a real treat. This is refreshing, engaging, and mature playing by Abduraimov which shows a deep understanding of the piece. The Turin orchestra plays well beyond their weight here, producing a wonderfully full sound. If they don’t have the polish of the Berliners for Abbado, they bring plenty of personality and swagger to the performance. I find Abduraimov’s playing masterful in terms of technique, but even more so in terms of interpretation. He can bring the fire when needed, but also has the wisdom to pull back and play with incredible lyricism. The opening of the Finale is accented unlike others I’ve heard, reflecting some real thought and vision behind the notes. Like Rana (see below), he is not afraid to play with emotion and personality, but Abduraimov also plays with an acute awareness of the composer’s intentions and language. I am also struck by the round tone he produces on the piano, something I’ve noticed on his other albums as well. This is a terrific recording.

The most recent recommended account is from the superb Italian pianist Beatrice Rana and the Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (Rome) with conductor Antonio Pappano, a 2015 recording on Warner. Rana ideally balances power and confidence with a lyrical sensibility that is delectable. She is a compelling musician, and doesn’t shy away from putting her personality into her performances. Rana finds the nobility and grandeur of this music, but like Horowitz and Argerich she never over romanticizes the concerto. Unlike some, Rana is sensitive to the rhythmic and dynamic pulse in Tchaikovsky’s music, and this can be heard well in the central section of the Andantino and throughout the Finale. Rana’s excellent touch can be heard well in the first movement’s quieter sections, but essentially she is a pianist that succeeds in building the drama and telling a story. For the first movement, this is precisely what is needed to hold it all together and prevent boredom. Rana is not capable of playing a boring note, and at least for me she keeps my rapt attention with anything she plays. The Santa Cecilia orchestra plays wonderfully here under studio conditions, with Pappano conducting with great sensitivity to the soloist (something that he honed in the opera pit). Tempos are moderate throughout, and the sound reproduction is very good.

Honorable Mention

There are some outstanding versions below as well, I encourage you to check them out as well.

LSO / Arthur Rubinstein / Sir John Barbirolli (EMI 1932)

LSO / Byron Janis / Herbert Menges (Decca 1960)

Vienna Symphony / Sviatoslav Richter / Herbert von Karajan (DG 1962)

LSO / Vladimir Ashkenazy / Lorin Maazel (Decca 1963)

RPO / Martha Argerich / Charles Dutoit (DG 1970)

LSO / Horacio Gutierrez / Andre Previn (Warner 1976)

BRSO / Martha Argerich / Kirill Kondrashin (Decca 1982)

NDR / Jorge Bolet / Gunter Wand (Profil 1982)

Montreal / Jorge Bolet / Charles Dutoit (Decca 1987)

Bournemouth / Peter Donohoe / Rudolf Barshai (Warner 1989)

Baltimore / Horacio Gutierrez / David Zinman (Telarc 1990)

Monte Carlo / Werner Haas / Eliahu Inbal (Decca 1993)

Atlanta / Andre Watts / Yoel Levi (Telarc 1994)

ASMF / Garrick Ohlsson / Sir Neville Marriner (haenssler 1996)

BPO / Volodos / Seiji Ozawa (Sony 2003)

RNO / Nikolai Lugansky / Kent Nagano (Pentatone 2003)

Sao Paolo / Yevgeny Sudbin / John Neschling (BIS 2006)

BRSO / Yefim Bronfman / Mariss Jansons (BR 2007)

Minnesota / Stephen Hough / Osmo Vänskä (Hyperion 2009)

Svizzera / Tiempo / Rabinovitch (Avanti 2011)

Mariinsky / Daniil Trifonov / Valery Gergiev (Mariinsky 2012) - special note here that this album seems to have been deleted from the catalog, and I can’t find a recording of it. If I can find it, I reserve the right to move it to the recommended category.

Saint Petersburg / Ingolf Wunder / Vladimir Ashkenazy (DG 2014)

Mariinsky / Denis Matsuev / Valery Gergiev (Mariinsky 2013)

RPO / Alexandra Dariescu / Darrell Ang (Signum 2016)

RSNO / Xiayin Wang / Peter Oundjian (Chandos 2018)

Lahti / Haochen Zhang / Dima Slobodeniouk (BIS 2019)

Join me next time when we will discuss #74 on the list, J.S. Bach’s Cello Suites. See you then!

________________

Notes:

Brown, David (2007). Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music. New York: Pegasus. ISBN 978-0-571-23194-2.

Maes, Francis, tr. Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002). ISBN 978-0-520-21815-4.

Morrison, Bryce. Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No 1; The Nutcracker-Suite. Gramophone Magazine. https://www.gramophone.co.uk/review/tchaikovsky-piano-concerto-no-1-the-nutcracker-suite.

Steinberg, M. The Concerto: A Listener's Guide, Oxford (1998). ISBN 0-19-510330-0.

Taruskin, Richard, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il'yich", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera (London and New York: Macmillan, 1992), 4 vols, ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 978-0-333-48552-1.

Taruskin, Richard, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, Volume One (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996) ISBN 978-0-520-29348-9.

Volkov, Solomon, Romanov Riches: Russian Writers and Artists Under the Tsars (New York: Alfred A. Knopf House, 2011), tr. Bouis, Antonina W. ISBN 978-0-307-27063-4.

Walker, Alan (2009). Hans von Bülow: A life and times. Oxford University Press. p. 213. ISBN 9780195368680.

Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973). ISBN 0-684-13558-2.

Wiley, Roland John, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

Wiley, Roland John, The Master Musicians: Tchaikovsky (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009). ISBN 978-0-19-536892-5.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_Concerto_No._1_(Tchaikovsky)

![Van Cliburn · Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1 & Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 2 (CD) [Japan Import edition] (2020) Van Cliburn · Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1 & Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 2 (CD) [Japan Import edition] (2020)](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!8jqy!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F28fc098b-decf-4da7-ab01-d335fa8bd997_300x300.jpeg)

![Tschaikowsky, Grieg - Nelson Freire, Rudolf Kempe, Münchner Philharmoniker – Konzert Nr. 1 B-moll Op. 23 Für Klavier Und Orchester / Konzert A-moll Op. 16 Für Klavier Und Orchester – Vinyl (LP, Album, Repress), 1972 [r6336528] | Discogs Tschaikowsky, Grieg - Nelson Freire, Rudolf Kempe, Münchner Philharmoniker – Konzert Nr. 1 B-moll Op. 23 Für Klavier Und Orchester / Konzert A-moll Op. 16 Für Klavier Und Orchester – Vinyl (LP, Album, Repress), 1972 [r6336528] | Discogs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!OKb1!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F24386e90-906d-464c-b2e1-b7c5d221fcd9_600x598.jpeg)

The Toscanini Rca recording is absolutely fantastic and live! It was for collecring money for war.

Why do you never mention pianist Earl Wild in your various concerto picks? He has one of the best Rachmaninoff concerto recordings (all 4), a fantastic Tchaikovsky concerto plus just about every other concerto. He has recorded tons of repertoire. You don’t even mention him in your honorable mentions.

Michael Rolland Davis