Building a Collection #72

Symphony No. 3 in C minor, Op. 78 “Organ”

By Camille Saint-Saëns

________________

It has been such a joy to make my way through some of the greatest music the world has ever heard, and to share my enjoyment with you the reader. My perspective is an amateur one, but I like to think we are on this journey together. We have happily arrived at #72 on our epic count up covering the top 250 classical works of all-time, and in this spot is the popular and powerful Symphony no. 3, nicknamed the “Organ” symphony by French composer Camille Saint-Saëns.

Camille Saint-Saëns

Camille Saint-Saëns was a composer of the romantic era in classical music, and he lived from 1835-1921. Saint-Saëns was also a pianist and organist, and in addition he was a poet and writer of some significance. Born in Paris, the young Camille was an extremely precocious prodigy, taking piano lessons at the age of just two and a half, and even composing a work at the age of three. He began studying composition at the age of seven, and at the age of ten he gave a concert which included Beethoven’s Piano Concerto no. 3, Mozart’s B flat concerto, K. 460, along with works by Bach and Haydn. In school Camille was a quick learner, picking up multiple languages and mathematics with ease.

Saint-Saëns entered the Paris Conservatory at the age of 13, studying the organ and composition. By his early twenties, he was already known to fellow composers such as Berlioz, Liszt, Gounod, and Rossini. From 1853 to 1876, Saint-Saëns earned a living by working as a church organist and teaching organ and piano lessons. However, throughout this time he also composed many works.

In 1875 Saint-Saëns married the much younger Marie Truffot, and in a tragic twist the two children they had together both died within weeks of each other, one from a four-story fall. Understandably this sent Saint-Saëns into a deep depression, and the marriage was dissolved in 1881. From that point on he spent a lot of time with the composer Gabriel Fauré and his family, often doting on Fauré’s children. Fauré’s family was very fond of him too.

Saint-Saëns had remained close to his mother through the years, and when she passed in 1888, he went into another depression. In order to try to pull himself out of it, he traveled and became especially interested in Egypt and north Africa. As music moved into the twentieth-century, Saint-Saëns’ music was increasingly sidelined in his homeland of France, as the avant-garde movement turned into modernism and France began celebrating such composers as Stravinksy, Ravel, Webern, Berg, and Schoenberg. But at the same time Saint-Saëns began becoming even more popular in the U.K. and the United States. During a tour of the United States in 1915, Saint-Saëns was warmly welcomed as the greatest living French composer. In his final years, Saint-Saëns stayed mostly to himself, living alone with his dogs. He died in 1921 in Algeria.

Saint-Saëns was gifted enough that he composed works in nearly every genre including opera, symphonies, concertos, songs, choral music, solo piano works, and chamber music. His most well-known works include his Piano Concerto no. 2, Symphony no. 3 “Organ”, the Danse macabre, the opera Samson et Dalila, and the beloved Carnival of the Animals.

Symphony no. 3 in C minor, “Organ”

Saint-Saëns’ most popular composition, his Symphony no. 3, the so-called Organ symphony, was composed in 1886. It is not really an organ symphony per se, but rather Saint-Saëns titled it Symphonie No. 3 “avec orgue” (with organ). Indeed, the organ only appears in the second and final movements, and the organ is not heard during the majority of the piece. It had its first performance on May 19, 1886, at St. James Hall in London in a concert by the Royal Philharmonic Society.

At the time of the symphony’s composition, there were relatively few French symphonies around. Classical music was dominated by the German speaking world, especially Haydn and Beethoven. But in the 1850s, that began to change with Saint-Saëns, Bizet, and Gounod all composing fresh and lively symphonies. Even in an age of cultural conflict, and political defeat at the hands of the Prussians, French composers still relied on the existing German models, especially Beethoven, for inspiration (with the exception of Berlioz, he was a unique case). It was nothing less than a national effort to compose “French” symphonies, and Saint-Saëns was at the forefront.

Although Saint-Saëns was a prolific composer, he had not written a symphony since 1859. The symphony was commissioned by the Royal Philharmonic Society in 1885. Saint-Saëns was touring around Germany at the time, and he had recently published a book titled Harmonie et Melodie. In the book, Saint-Saëns took the view that Wagner was not to be included in the pantheon of great German composers (Saint-Saëns was especially fond of Mozart), and that he was not a good model for young composers. Of course this was heresy in Germany, and Saint-Saëns was mercilessly attacked in the press. In fact, some cities refused to welcome him. Nevertheless, Saint-Saëns began work on his symphony with clear homage to the giants of the symphonic form, Beethoven and Schubert. Saint-Saëns’ good friend and mentor Franz Liszt passed away in July of 1886, and Saint-Saëns dedicated the symphony to Liszt’s memory.

Saint-Saëns’ choice to write a symphony for the commission from London was unusual for a few reasons. First, Saint-Saëns was primarily known for writing concertos and tone poems, and he had not written a symphony in a long time. Second, French composers had generally avoided writing symphonies. Some scholars see Saint-Saëns’ decision to write a symphony as a direct response to the growing popularity of Wagner’s style and compositional techniques in France. Saint-Saëns viewed Wagner’s musical language as fundamentally incompatible with French character and culture. He even told young French musicians, "young musicians, if you wish to be something, remain French!". Thus, it is thought that a symphony represented Saint-Saëns’ way of responding to this trend by using the very form that Wagner had declared dead after Beethoven. In this sense, Saint-Saëns’ symphony was a classically structured and inspired response to Wagnerism. But it also shows that Saint-Saëns was essentially a conservative composer more closely tied to traditional forms and, like Brahms, primarily looked back at history and infused those traditional forms with his own individual voice.

Famously, when the symphony was finally played in Paris later in 1886, Gounod came from the concert declaring “Voila le Beethoven francais!” (“Here we have the French Beethoven!”). The symphony’s final movement begins with a grandiose C major chord played on the organ, and the main theme is introduced accompanied by a lovely piano part. It will certainly leave an impression on you. Although the final movement suggests joyful triumph, the symphony as a whole is more varied. There are several searching passages, as well as some truly beautiful passages with the strings (especially in the Poco adagio second movement).

The symphony’s structure is as follows:

Adagio – Allegro moderato – Poco adagio

Allegro moderato – Presto – Maestoso – Allegro

In addition to the bold move of adding organ to a symphony, Saint-Saëns also added a piano part which adds to the color palette in an interesting way. Saint-Saëns also divided the symphony into two parts, although in reality the four major sections are still easily identified. Saint-Saëns wrote in the program notes for the London premiere:

This symphony, like its author's fourth Pianoforte Concerto, and Sonata for Piano and Violin, is divided into two movements. Nevertheless, it contains, in principle, the four traditional movements; but the first, arrested in development, serves as an Introduction to the Adagio, and the Scherzo is linked by the same process to the Finale.

The symphony cycles through its thematic material, derived from fragments of ancient melodies, in a unifying way; each melody appears in multiple movements. Saint-Saëns also employs Liszt's method of thematic transformation, so that these subjects evolve into different guises throughout the symphony.

Saint-Saens was truly proud of his work, and he knew he had put his whole heart into it. He was quoted as saying, “I have given it all that I had to give. What I have done I shall never do again.”

The Essential Recording

The 1959 recording by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Charles Munch from RCA Living Stereo is one of my favorite recordings of all time. Charles Munch was Alsatian born, and through his 13-year tenure in Boston (1949-1962), he championed a lot of French music, particularly Debussy and Ravel. Due to being one of the primary orchestras used by the RCA Victor label for recordings during that time, and also touring the USA and the world extensively, Munch became very well-known. Boston also had the benefit of having one of the greatest concert halls in the world in my opinion, Boston’s Symphony Hall.

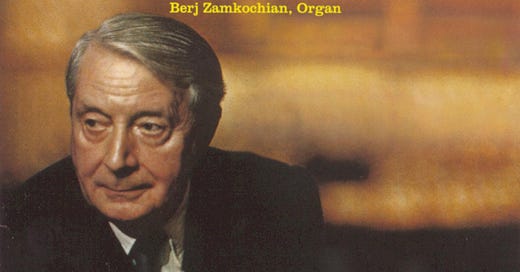

Munch was sometimes faulted for not being very subtle in his conducting style, and at times his recordings are almost too overt. However, it is this very style that I find works quite well with this symphony. There is nothing routine about it, and there is an electric quality to the performance which is unmatched. The first movement is taken at a pretty fast clip, and this only adds to the excitement. The strings and brass are captured gloriously here, and Munch presses forward in all the appropriate places. The organ part is played by Berj Zamkochian, sensitively in the second movement, and then to spine-tingling effect in the final. The organ symphony presents challenges in recordings especially, due to the difficulty of keeping the timing and balance proper between the organ and orchestra. You will notice at the beginning of the huge final part, there are some moments of audio overload with the organ. If anything, I think this adds to the realization that this was a groundbreaking recording that was trying to capture a wide dynamic picture.

Munch’s tendency to overemphasize staccato playing, something you might have also heard with Toscanini, for me is just about right for this symphony. This is a white-hot performance of a grand symphony, recorded with what was state-of-the-art technology at the time. I would never want to be without it. There are other fine recordings of this symphony, but none of them put all the pieces together the way this one does.

A word about the Living Stereo sound on this recording. The way the performance was recorded is somewhat artificial in the sense that some parts of the orchestra and the organ are spotlight and up close. This is not the kind of sound you might hear if you go to the concert hall, and so in that sense it is not the most natural sound. Still, in terms of technology and allowing the listener to hear details more clearly, the recording is simply stunning for 1959.

Recommended Recordings

Saint-Saëns’ Organ Symphony is notoriously difficult to record well, and consequently there are relatively fewer recommended recordings than I’ve had for other works. Getting the balance right between the organ and the orchestra is not easy, which gets into the question of whether the organ is in the same location as the orchestra or dubbed in from another location. The dubbed option is more common, though that presents challenges to engineers which hasn’t always worked out well.

One of the few recordings that rivals the Munch above is from the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra with conductor Louis Frémaux and Christoper Robinson on organ, recorded by EMI in 1972 (it is now on the Classics for Pleasure label). Frémaux succeeds in injecting vitality and electricity into the performance, along with revealing plenty of details. While the sound doesn’t have the immediacy of the Munch recording, it does have a more natural sound similar to being in the concert hall. There is a moderate push forward in momentum in the first and last movements, and the Poco adagio is one of the best in the catalog. Frémaux doesn’t rush this movement and allows the waves of sound to build which maximizes the emotional impact. The organ in the final movement is appropriately grand, though the rest of the orchestra fades in the balance a bit too much. But overall, this is one of the best.

French conductor Jean Martinon was a major talent but was mostly known for his interpretations of French repertoire. He had recorded Saint-Saëns’ Organ Symphony in 1971 with Marie-Claire Alain on organ, but in 1975 as part of a project where he recorded all the Saint-Saëns symphonies, he recorded it again with the Orchestre National de l’ORTF (French National Radio and Television Orchestra) with Bernard Gavoty on the organ for the Erato label (Warner). This is an excellent performance, thoughtfully expressed and thoroughly idiomatic. The organ is “French” sounding if you will, which for me means it is reedier and more plangent than you might hear in other recordings. I quite like it. Martinon doesn’t try to score cheap points by reveling in pure sound quality, but he reads the work as a whole. Therefore, you hear a thoughtful and sensitive Poco adagio followed by a dramatic and fun Allegro Moderato-Presto. Details are not glossed over or hidden by the sheer sound of the organ either, and Martinon never pushes too hard. The acoustic space is a tad over-reverberant, but not problematic. This is a loving account which I enjoy more with each repeated listening.

Long time readers will know I am not really a fan of Daniel Barenboim the conductor (though his pianism is another matter entirely), but even I must bow in the presence of greatness. His 1976 recording of the Organ Symphony on Deutsche Grammophon with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and organist Gastion Litaize is a powerhouse of a performance, and one that I return to often. The famed brass of the CSO are captured marvelously, and the organ part (which was recorded in Chartres Cathedral in France and dubbed into the recording) is plangent and epic sounding. For once Barenboim doesn’t take it easy but rather elicits a high energy performance full of life. Fair warning, the older DG versions of this recording had very dry sound, but the more recent “Originals” remastering seems to have helped a great deal. There is more warmth and depth, and the dubbing of the organ is almost ideal. I regard this as one of Barenboim’s greatest triumphs on the podium.

Despite my reservations about conductor James Levine as a person, the fact remains he left us many outstanding recordings. One of them is his 1986 Deutsche Grammophon recording of the Organ Symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic and organist Simon Preston. The sound is spectacular, and Levine’s big boned reading is dramatic but also musically satisfying. The organ part was dubbed, while the orchestral part was recorded in the Philharmonie in Berlin. Fortunately, the dubbing was convincingly done, and the organ’s impact is thrilling. The album also includes one of the finest recorded versions of Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

The 1997 EMI (Warner) recording by French conductor Michel Plasson and the Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse with organist Matthias Eisenberg remains one of my favorites. The organ on this recording has a unique French sound to it, reedier than you usually hear, and I enjoy it. Plasson leads a performance blazing with energy and excitement, and the momentum in the buildup to the ending is breathtaking. Other sections find a greater amount of transparency generated from the Toulouse band leading to greater detail, and the recording venue of Notre Dame La Daurade basilica in Toulouse has a good atmosphere for the sound. The recording balance is not always ideal between the organ and the orchestra, and the extremely wide dynamic range can surprise the listener at times. But in terms of interpretation and performance, this has that special something which I always find satisfying. Just listen from 6’50” to about 8’15” in the Allegro moderato, so well done.

Honorable Mention

Why is the honorable mention list so short? This deserves a comment. The Organ Symphony is challenging to record well in my opinion, and at times you have a terrific organ performance let down by a lackluster orchestral performance (or vice versa for example with Mehta’s Los Angeles recording where the organ is awful in the final movement). One such example is Eugene Ormandy and The Philadelphians in 1984 with organist Michael Murray on Telarc. The organ is tremendous, but Ormandy’s direction of the rest of the symphony disappoints in my view. Bernstein’s and Karajan’s efforts with the symphony are average at best, and some recent outings such as that from Michael Stern and the Kansas City Symphony which boast outstanding sound, don’t compare to the best on performance grounds. Some readers may have a different opinion, and I welcome your comments. But the recordings below are nearly the equal of the recommended list above.

Detroit Symphony Orchestra / Dupré / Paul Paray (Mercury 1957)

The Philadelphia Orchestra / Fox / Eugene Ormandy (RCA/Sony 1974)

Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal / Hurford / Charles Dutoit (Decca 1982)

Orchestre de l’Opera Bastille / Matthes / Myung-Whun Chung (DG 1993)

That’s it for this edition of Building a Collection. Thank you once again for your readership! Join me next time for #73 on the list when we discuss Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto no. 1. See you then!

__________

Notes:

Burk, John 1959. A Hi-Fi Spectacular! Saint-Saens Symphony No. 3. Debussy La Mer. Ibert Escales. RCA Victor Living Stereo Liner Notes. Pp. 3-7.

Cummings, Robert. Camille Saint-Saëns. All Music Guide to Classical Music. All Media Guide. 2005. Pg. 1145.

Deruchie, Andrew (2013). The French Symphony at the fin de siècle: Style, Culture, and the Symphonic Tradition. Rochester, New York: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-838-1. OCLC 859154652.

Fallon, D. M. (1973). The Symphonies and Symphonic Poems of Camille Saint-Saëns (PhD thesis). Yale University.

Macdonald, Hugh 2013. Camille Saint-Saens, Symphony no. 3, Opus 78 (“Organ Symphony”). Boston Symphony Program Notes, Week 19. 2012-2013 Season. Pp. 43-49.

Pasler, Jann (2009). Composing the Citizen: Music as Public Utility in Third Republic France. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. doi:10.1525/california/9780520257405.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-520-25740-5. OCLC 808600746.

Saint-Saëns, Camille (1885). Harmonie et mélodie. Paris: Calmann Lévy.

Service, Tom (25 February 2014). "Symphony guide: Saint-Saëns's Third (the Organ symphony)". The Guardian.

Smith, Rollin (1992). Saint-Saëns and the organ. Stuyvesant, New York: Pendragon Press. OCLC 1200567999.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symphony_No._3_(Saint-Sa%C3%ABns)

One of my favorite symphonies.

Some other recordings I like are Edo De Waart, both with Rotterdam and San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, Eschenbach with Philadelphia Orchestra (slow but powerful) and Batiz with London Philharmonic Orchestra.