Building a Collection #69

Piano Sonata in B minor, S.178

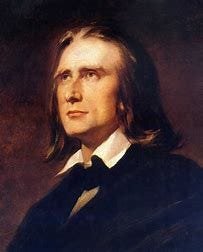

Franz Liszt

________________

Welcome back to Building a Collection, a series which is part of the larger newsletter Building a Classical Music Collection here on Substack. The Building a Collection series is in the process of covering the top 250 classical works of all-time, and as a reminder we are counting upwards. We have reached #69 on the list, and we arrive at our first encounter in the survey with the pianist and composer Franz Liszt, and what is generally considered his greatest composition, the great Sonata in B minor for solo piano. This kaleidoscopic and colorful work is a favorite of many pianists and listeners alike, and at a running time averaging about 30 minutes, it is an epic, large scale work with many different personalities contained within its score.

Franz Liszt

Hungarian pianist, composer, conductor, and teacher Franz (Ferenc) Liszt (1811-1886) was one of the most important figures from the Romantic period of classical music. While Liszt composed in many forms, it is particularly his piano music which is best known and for which his influence has left its most significant mark. Equal or greater to his work as a composer was his colorful career as a concert pianist.

Growing up in the Kingdom of Hungary, which at the time was part of the Austrian Empire, Liszt was recognized as a musical prodigy at an early age. His father Adam, who apparently knew the composers Haydn and Hummel personally, was an avid amateur musician, and encouraged his son’s interest in music. The young Franz’s first concert in public took place at the age of nine, and by then he had already been improvising at the piano for several years. But that first concert, and others soon after for dignitaries, led to several wealthy benefactors offering to finance Franz’s further education in Vienna. In Vienna, Franz would study piano under Carl Czerny, who himself had been a student of Beethoven and Hummel. Indeed, so impressed was Czerny with the young Liszt that he offered to teach him for free for almost the next two years at which point he declared he had nothing further to teach him. Antonio Salieri, rather infamously and inaccurately depicted in the film Amadeus, also taught the young Liszt and was similarly struck by the young man’s natural talent and improvisatory abilities.

Liszt’s first public recital in Vienna in December 1822 was a rousing success, and he subsequently met both Beethoven and Schubert. After Liszt’s final public concert in Vienna, Beethoven himself was reputed to have walked on stage to kiss Liszt on the forehead as some sort of musical benediction to indicate his favor upon the young pianist. It is a nice story, but its veracity cannot be confirmed. In any case, Liszt’s father moved the family to Paris about this time to capitalize on the talent of his young son, as Paris was at that time the artistic capital of the world. In 1824 at the age of 11, Liszt remarkably wrote his own Variation on a Waltz by Diabelli, which was included in a publication of 50 famous variation pieces written on Diabelli tunes. Liszt was the youngest composer of those included in the book.

During the years 1824-1826, Liszt gave an extensive series of concerts in France and England (even performing before King George IV), and his family made a lot of money from his performances. Liszt attempted to gain entry to the Conservatoire de Paris, but at that time foreigners were banned. Sadly, Liszt’s father Adam died rather suddenly in 1827 and for several years thereafter Liszt continued living in Paris with his mother. However, he stopped touring during this time and began taking on private students for lessons. He worked long hours, and it seems he took up drinking and smoking in these years, habits he would maintain throughout the rest of his life. Liszt also fell in love with one of his students, the daughter of a government official, but her father broke off the affair.

Shortly after Liszt became ill and nearly died, an experience which sparked renewed introspection and an intense interest in religion. Liszt was a devout Roman Catholic, and around this time he almost became a priest but was dissuaded by a priest friend of his. For a time, he stopped teaching and performing altogether, and he befriended several literary and visual artists of the time including Victor Hugo, Alphonse de Lamartine, George Sand, and Alfred de Vigny. In 1830, shortly before the premiere of Symphonie Fantastique, Liszt met Hector Berlioz. Berlioz had a significant influence on Liszt, and they became good friends. Around this time Liszt also met Frédéric Chopin.

In 1832 Liszt attended a concert where the violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini performed, and it so inspired Liszt to the point where he was determined to become as impressive on the piano as Paganini was on violin (Liszt would later write his Grandes études de Paganini in Paganini’s honor). Liszt went back to work on the piano, practicing many hours every day. A tour of Europe was planned where Liszt would give solo recitals in many cities. About the same time Liszt began a relationship with the Countess Marie d'Agoult (a married woman), and to avoid scandal they moved to Geneva where their daughter Blandine was born. Between 1835-1839 they traveled around Switzerland and Italy, with Liszt performing along the way. Liszt’s splendid work Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage) came out of these travels. The couple’s daughter Cosima was born in 1837, and their son Daniel was born in 1839. Their relationship became increasingly strained as Liszt began touring Austria and then Hungary, and the couple finally separated in 1844.

From 1841 a phenomenon of ecstatic enthusiasm for Liszt’s pianistic performances began to grow around Europe, for which was coined the term “Lisztomania” (dubbed so by Heinrich Heine in 1844). Liszt was touring across Europe to great popularity which one critic described as “mass hysteria”. Liszt had more than a touch of the showman in him, and he took full advantage of throngs of admirers, often throwing his gloves and handkerchiefs to adoring fans. At the time Liszt struck an attractive figure, and his stage presence was almost hypnotic to fans. Some estimates say Liszt appeared for public performances over one-thousand times in an eight-year period. He instantly became the toast of whatever city hosted him, and even after mostly retiring from performing, his fame from this period of time lived on. Far from being a shallow human being, Liszt was known to donate nearly all of his income to charitable and humanitarian causes, giving large sums to hospitals, churches, and schools.

Liszt retired from performing in his prime at the age of 35, retiring in Weimar to settle down a bit. From 1849 to 1859 Liszt was given the title of Kappelmeister Extraordinaire in Weimar. Liszt organized concerts and supported the music of rising artists, chief among them Richard Wagner. Liszt has often been identified as the beginning of the “New German School” of composers, which also included Berlioz and Wagner. The old guard of German composers such as Mendelssohn and Brahms looked backward to tradition, while Liszt and company were more forward looking. Of course, this is a generalization and any tension between the two movements has largely been academic.

In 1859 Liszt’s 20-year-old son Daniel died suddenly due to an unknown illness. After a failed attempt to marry Polish Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein in 1861 in Rome, Liszt encountered more tragedy in the form of the death of his first daughter Blandine after she contracted sepsis from a medical procedure. Liszt vowed to retreat to a solitary life, which he did by moving to the Madonna del Rosario monastery outside Rome where he took up residence in a tiny cell in 1863. After having joined the Third Order of Saint Francis in 1857, he received the tonsure from the Church in 1865. Liszt would receive other minor religious orders throughout the rest of his life. Even though primarily confined to his cell, Liszt had a piano and continued to compose.

The last decade or so of Liszt’s life he traveled extensively between Rome, Weimar, and Budapest, often agreeing to teach young musicians or to give masterclasses. In 1881 Liszt fell down some stairs and was in bed for weeks after. But the biggest ailment he had at that time may have been his lingering and debilitating depression and terror of death. He carried on, even making a trip to Bayreuth in 1886 to support his daughter Cosima in her attempts to carry on with Wagner’s Bayreuth Festival (Wagner had died in 1883). But Liszt became frailer, developed pneumonia, and died on July 31, 1886, at the age of 74.

In addition to his reputation as a pianist, many of Liszt’s compositions live on in standard repertoire. These include his Sonata in B minor, 19 Hungarian Rhapsodies, Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, La Campanella, Mephisto Waltz no. 1, Liebestraum, Transcendental Etudes, Les préludes, Années de pèlerinage, Piano Concertos nos. 1 & 2, A Faust Symphony, Paganini Etudes, La Lugubre Gondola No.2,Deux légendes, Mazeppa, Consolations, and Totentanz.

Liszt coined the musical terms “transcription” and “paraphrase”, with a transcription being a relatively faithful reproduction of a score for instruments other than the original, and a paraphrase being a looser and more free interpretation of the original. Liszt would write many, many of these categories of pieces, perhaps almost half of his entire output. Indeed, today Liszt’s own transcriptions of Beethoven’s symphonies for piano remains the primary version. In Liszt’s time it was often difficult to find the musicians to play orchestra music or it could be tough to arrange performances with travel being required. Thus, Liszt did a service by providing transcriptions so that a wider array of music could be heard by a larger audience. Also, in using his considerable improvisational gifts Liszt advanced German compositional technique and many of his paraphrases are works of utter genius.

The influence of Franz Liszt on composers of subsequent generations can hardly be overestimated. Indeed, next to Wagner, Liszt may have had more impact than any composer from the Romantic period. In terms of his departures from tonal music and traditional harmonies, Liszt consistently broke new ground. His novel use of form and thematic material was unique, especially how he integrated folk music as well as modern chromaticism into his work. The early twentieth century saw modern music overreact against romanticism by adopting a more objective type of music (such as you might hear with Stravinsky, Schoenberg, or Bartók). It wasn’t until several decades later, in the 1950s, that Liszt’s music was rediscovered to an extent, and his compositional genius was more fully appreciated. In any case, you cannot separate Liszt the composer from Liszt the showman completely, as his music has a certain flamboyance and flash which makes it, well, Liszt. Other composers that credited Liszt with influencing their work include Debussy, Kodály, Dohnányi, Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Saint-Saëns, Sibelius, Smetana, and Richard Strauss.

Sonata in B minor

Liszt’s one and only piano sonata was composed while he was in Weimar in 1852-53 and was published in 1854. It was dedicated to fellow composer Robert Schumann, who had dedicated his Fantasy op. 17 to Liszt in 1839. For both Schumann and Liszt, the sonata had become a somewhat worn-out form, even though they both grappled with how to maintain the form’s structural link to the past while at the same time progressing forward with their own ideas. Franz Schubert had also done this with his Fantasy in C major “Wanderer”,

Liszt’s Sonata in B minor is in a single movement, contains coherent themes, and maintains elements of the sonata structure. Franz Schubert had also done this with his Fantasy in C major “Wanderer”, a piece Liszt definitely knew about since he had transcribed it for piano and orchestra in 1851. But even with this precedent, Liszt’s Sonata was progressive in his complete rethinking of how a sonata should be structured. Liszt was familiar with symphonic poems, himself writing several including Mazeppa and Les préludes, and so essentially what he did with his Sonata in B minor was apply some of the same principles to a solo piano work. Liszt takes a few basic themes and transforms them as the sonata progresses, but still within a formal structure which can be fairly easily followed.

Even though the Sonata is in one movement, listeners and scholars over the years have broken it into three or four (or more) distinct sections based on themes and tempos based on the indications in the score, and some recordings even index the piece this way to make it easier. The most common breakdown is as follows:

Lento assai -

Allegro energico -

Grandioso -

Recitativo -

Andante sostenuto -

Quasi adagio -

Allegro energico -

Piu mosso -

Stretta quasi Presto -

Presto - Prestissimo -

Andante sostenuto -

Allegro moderato -

Lento assai -

The Sonata takes us on quite a journey filled with sparkling virtuosic runs, darkly brooding moments, tender, gentle, and sentimental themes, as well as powerfully explosive and energetic passages. Dynamics run the gamut between extremely quiet all the way to extremely loud, while tempos vary as well from almost stopped to very fast passages. It is a piece that tests the pianist’s skill at every turn, one moment lyrical and the next moment off to the races. But Liszt also allows flexibility and freedom of invention (to a point).

Because Liszt was fond of “programme” music, a phrase he coined after hearing Berlioz’s Harold in Italy, for music which is "driven by an overarching poetic image or narrative". Scholars have been trying to make sense of his Sonata in the context of a program Liszt had in mind, but this divides opinion. Liszt scholar Alan Walker outlines some of the more likely possibilities:

The Sonata is a musical portrait of the Faust legend, with Faust, Gretchen, and Mephistopheles themes symbolizing the main characters.

The Sonata is autobiographical; its musical contrasts spring from the conflicts within Liszt's own personality.

The Sonata is about the divine and the diabolical; it is based on the Bible and on John Milton's Paradise Lost.

The Sonata is an allegory set in the Garden of Eden; it deals with the Fall of Man and contains God, Lucifer, Serpent, Adam, and Eve themes.

The Sonata has no programmatic allusions; it is a piece of "expressive form" with no meaning beyond itself.

The Sonata is complex, and no interpretation has been widely accepted. It seems reasonable to conclude that the Sonata contains all the elements Liszt himself possessed in his personality: emotionality, expressiveness, nobility, evil, holiness, and showmanship. As far as the music itself goes, it undergoes many transformations throughout the Sonata. The program annotator for the Los Angeles Philharmonic comments:

The Sonata begins (and ends) in a kind of desolate mist, with a descending, tonally ambiguous scale in the piano’s bass. A sudden explosion brings on an impetuous, taut theme in octaves, followed by a brief rhythmic motif that begins with repeated notes. After these two ideas vie with each other, and the opening scale reappears, this time greatly intensified, there appears a simple but grandiose major-key theme with a repeated chord accompaniment – the apotheosis of the extravagant romantic spirit. In a work built almost wholly on thematic transformation, this theme alone remains unchanged in its reappearances, other than for its minor-key manifestations.

From this point on, the basic thematic materials are transformed into elements which rage demonically, caress angelically, disport themselves diabolically, and struggle monumentally. Throughout the work, the drama, which can be thought of as falling into movements, is projected through immensely difficult pianistics, and through lyricism requiring the most elegant tonal refinement. Ultimately, however, the demand on the performer for architectural delineation and poetic ardor is as great as for virtuosic command and superhuman strength, all these resources being required to bring this massive piano tone poem into Lisztian focus.

The Sonata was first performed publicly in Berlin in 1857 by Hans von Bülow. Predictably the acerbic critic Eduard Hanslick wrote of the work "anyone who has heard it and finds it beautiful is beyond help". Brahms reportedly fell asleep while listening to Liszt perform it, and the famous pianist of the time Anton Rubinstein did not care for the work. However, Richard Wagner praised the work. It took a good amount of time for the piece to become widely accepted and to be given its due, the perception being it was ridiculously difficult to play and was seen as too progressive and too “new”. By the turn of the century, the piece had gained a foothold as one of Liszt’s most brilliant conceptions and even with the modern music movement in the twentieth century, the Sonata continued to become popular and now is one of the most performed and most revered piano works of all-time.

Essential Recordings

Because almost every virtuoso pianist of the past century has recorded Liszt’s Sonata in B minor, there are loads of recordings and an astonishing number of recommended recordings. Therefore, I will try to keep my review of each recommendation brief. Liszt has never been high on my list of favorite composers, but I must admit that getting to know the Sonata through many hours of listening I have come to love this piece.

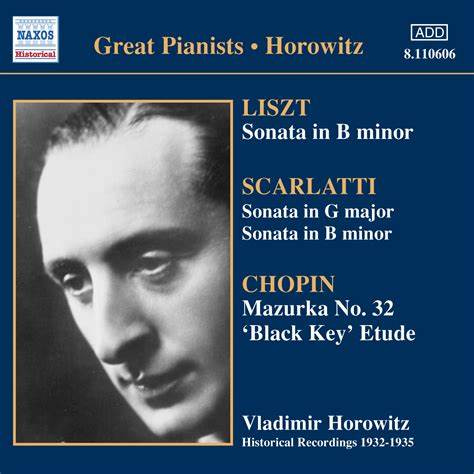

Recently I haven’t had many “essential” recordings to recommend, but for Liszt’s Sonata I have three essential recordings. The first is from 1932 by piano legend Vladimir Horowitz, a recording which has been on various labels, but I heard it on the Naxos label (via idagio). The Liszt Sonata would seem to fit Horowitz’s temperament and style like a glove, and so it proves an ideal fit on this early recording which features the fire breathing version of the pianist before his interpretations became a bit more mannered. Recorded at Abbey Road in London, there is some background noise and boxiness in the sound, but it is really quite good for 1932. What I am looking for in the Sonata is not just virtuosity, but how well the pianist uses phrasing, tempo, and dynamics to enhance their interpretation. Horowitz had technique to spare, so the virtuosity is never in question. But Horowitz had the nerve and bravado to play at the extremes if he believed it served his vision of the piece, as he does here. He didn’t shy away from expressivity and emotional involvement and could be extra vulnerable and tender in his playing. But he could also play with undeniable power and assertiveness. An occasional wrong note didn’t concern him, it was the overall impression made on the listener that counted. Horowitz makes the piano thunder when needed (listen at 9’55”) but can also pull off a true pianissimo in the Andante sostenuto passages (listen at 12’15”). Clocking in at 26:33 this is on the faster side, but it certainly doesn’t feel rushed. Horowitz’s complete conception here is more fulfilling than his later recordings.

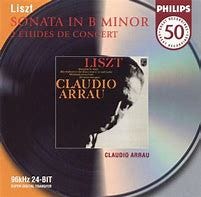

For the second essential recording we fast forward to 1970 and the benchmark recording made by the Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau for Philips/Universal. Considered one of the finest Liszt interpreters of all-time, Arrau had a particular affinity for this music. In terms of depth and lyricism, this recording has no match. Arrau never feels the need to use dynamics and tempo the way Horowitz and Argerich do, but rather he lets the music and Liszt’s own indications speak for him. Therefore, this recording clocks in at about 32 minutes, slower than the other two essential recommendations. What Arrau offers us is a version of probing expressivity, more typically romantic phrasing, a lingering longer in slower and more lyrical passages, and an almost spiritual tonal quality which disarms the listener. Has the Andante sostenuto ever been played so affectingly? Arrau has the virtuosity in his bag but only uses it to further the story told by the music. While Horowitz and Argerich may capture the demonic quality better, Arrau is darn close, and he takes the prize when it comes to successfully pulling off Liszt’s overall vision most consistently and satisfyingly. In short, a brilliant recording.

Now for the final essential recording is one made shortly after the Arrau above. As frequent readers probably know, I am an unabashed fan of Argentine pianist Martha Argerich. Her sensational 1971 debut recital recording for Deutsche Grammophon (made at the Akademie der Wissenschaften in Munich) was a blockbuster in the classical music world, and the Liszt Sonata from the album is essential listening. In her daring and extroverted approach, Argerich has a lot in common with Horowitz. Her reading here and the one above from Horowitz possess fire in the belly along with an uncanny ability to change moods and dynamics on a dime. Just listen to Argerich between 5’00” and about 6’50” and you will hear magisterial playing with a sensitivity that is unmatched. The faster passages are played with Argerich’s typical intensity and power. Argerich is not afraid to thunder the keys too (listen at 9’15”), and if her frenetic style doesn’t appeal to you, just wait until she slams on the brakes (which happens more than once). The sound she creates from the keyboard is distinctive, but more importantly she never misses the emotional core in this performance. Once again, even though this is a faster traversal at 25:49, in the overall conception I never feel it is rushed. Sample again from 13’20” through 14’00” and if you don’t get goosebumps, you may have a problem. I realize I am biased toward Argerich, but I still say this is something very special.

Other Recommended Recordings

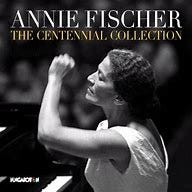

The great Hungarian pianist Annie Fischer is another favorite of mine, and her 1953 recording on Hungaroton is on my list. Fischer studied at the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest with Dohnányi, and so this music is in her blood. Despite the boxy sound, poor even for its time, Fischer brings distinction and integrity to the Sonata. Fischer specialized in Mozart and Beethoven, and so her reading of the Liszt is more classically structured and emotionally restrained compared to some others. But there is power and logic to her approach, and like Arrau she doesn’t rush through the faster passages.

The phenomenally talented Soviet Russian pianist Lazar Berman was very adept with Liszt and Rachmaninoff, and his Liszt Sonata from 1955 (when he was only 25) now on Brilliant Classics and streaming services, is one of the finest. Berman was overshadowed by Gilels and Richter in the Soviet Union, and it didn’t help him that he was Jewish and married a French woman. In any case, he wasn’t really given his due until he started performing in the west after 1990. Berman gained a reputation for playing fast and loud, which was unfair as a generalization, but this recording shows both his virtuosity as well as his ability to play with more finesse and sensitivity. Still, the larger-than-life qualities of the piece are brought out marvelously by Berman.

The great Soviet Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter recorded the Liszt Sonata several times, but for me it is his live account from 1958 in Moscow on the Urania label that is the finest. Others will disagree. His 1965 Carnegie Hall performance has many fans, although for me the sound is problematic. His Philips studio account sounds harsh and aggressive. Richter has a few smudged notes, but the sense of power and spontaneity he produces is breathtaking. He is able to alternate energy with tenderness, as well as heart and intellect, in ways only Horowitz and Argerich can rival. The early climax at 3’30” is noble, the faster passages are amazing (listen from 7’25” to around 8’45”), and the Andante sostenuto is sublime. The sound is good from a live recording of that time.

If you had told me I would include English pianist Clifford Curzon in a survey of Liszt Sonata recordings, I would have been skeptical. In my mind, Curzon specialized in classical composers such as Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms rather than the romantics such as Liszt. I was not aware that Curzon played a lot of romantic composers in the early part of his career, and it is clear that Liszt’s Sonata was a favorite of his. I am recommending not just one, but two Curzon recordings of the Sonata: Curzon’s 1961 live performance from the Edinburgh Festival on the BBC Legends label, as well as Curzon’s 1963 studio recording from the Sofiensaal in Vienna on Decca. The live recording has marginally more electricity and spontaneity but also has a few missed notes and is not as well recorded as the Vienna version. On both performances one has the sense that Curzon has thrown his classical sensibilities out the window and has almost been possessed by a different pianist altogether. He takes risks that pay off, and he sounds much more spontaneous than on some of his rather staid Mozart recordings. The juxtaposition between the softer, lyrical moments and the frenzied Allegro energico passages is striking. While Curzon certainly hews to an organized, classical approach, it is clear that he was uniquely inspired by this piece.

I am fond of Soviet Russian Emil Gilels’ wonderfully played and recorded Sonata from 1965 on RCA/Sony. Gilels, like Fischer, takes a more classical approach to the Sonata without some of the extremes of Horowitz or Argerich. While not quite as expressive or lyrical as Arrau, Gilels gives proper weight and space for the music to inhabit, and his pacing is near ideal. Besides displaying more than enough virtuosity and lyrical touch, Gilels creates an appealing, golden tone and he knows how to build the tension and drama. A good mainstream choice in terrific sound.

Austrian pianist Paul Badura-Skoda was a student of the great Edwin Fischer and carried on that tradition with the Austro-German composers such as Mozart, Schubert, and Beethoven. However, he had a vast repertoire and his live recording of the Sonata from Carnegie Hall in 1965 (on the Gramola label) has been described as one of Badura-Skoda’s greatest achievements. This is a performance of inspiration, full of energy and fury. The technical assurance is there, but a great deal besides in terms of insight and personality. There is a consistent background hiss on the live recording, and the stereo sound on my headphones came in and out. Badura-Skoda should be more well-known, and this recording shows us why.

The late Brazilian pianist Nelson Freire was one of my favorite interpreters of the romantics, and his 1972 recording of the Sonata (now in a Sony boxed set dedicated to Freire) is eminently recommendable. Freire’s playing has a clear and full tone, and the beauty and elegance of his technique is immediately evident. Freire is closer in style to Arrau than Horowitz, and Freire is at the service of the music. Freire eschews pounding on the piano, as well as making dramatic dynamic changes, so we are left with a graceful reading with a lot of character and beauty. It is a magisterial reading, with less pushing and pulling as you might hear with some of the others on this list.

Cuban American Jorge Bolet was a marvelous match for the music of Liszt, and I love both his 1960-61 account on the Everest label, as well as his 1983 digital recording for Decca. The readings are different however, with the earlier account being more energized and spontaneous and the later account more laid back and lyrical (in richer sound). If the Everest recording lacks a bit of sonic depth, it is certainly the more involved and interesting account. Bolet shows his dramatic personality, as well as his imagination in making the piece his own. Bolet could play fast and was known as a “romantic virtuoso”, but his playing certainly does not lack subtlety or feeling. The Everest account is several minutes faster, with more tension and fire. But I must also put in a recommendation for the Decca recording, which has Bolet creating a golden tone (much like Arrau) and which shows a more lyrical side than the earlier recording. Bolet’s shading and phrasing here are gentler, but also more satisfying in a way. This is truly a romantic reading in the best sense. Either way, you shouldn’t miss Bolet’s Liszt.

Polish pianist Krystian Zimerman has become one of the most beloved pianists alive today, but when he recorded the Liszt Sonata in 1991 for Deutsche Grammophon he was only 35 years of age. Zimerman excels in Chopin and Liszt, and his recording of the Liszt concertos with Ozawa in Boston is still a landmark recording. His Liszt Sonata has many of the same qualities such as clarity, power, and expressive depth. Zimerman is never less than controlled and disciplined, but he creates a palette of almost overwhelming sweep and impact. The fugue immediately after the Andante sostenuto is dazzling and impressive, and how Zimerman handles the Allegro energico section toward the end is almost unbelievable in its virtuosity. The piano sound is full and immediate. As a standard choice for the Sonata, this would be a very fine pick.

The Croatian pianist Ivo Pogorelich (Pogorelić) divides opinion. Some find his performances too far outside the box or too far astray from the composer’s intentions. In 1980 he entered the X International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw but was eliminated in the third round, prompting juror Martha Argerich to resign from the jury in protest, calling Pogorelich a "genius". This action by Argerich precipitated a major scandal in the world of classical music. Her action was supported by two other jurors, who declared that it was "unthinkable that such an artist should not make it to the finals". But his 1991 recording of the Liszt Sonata shows all the positives of Pogorelich with very few of the drawbacks. Yes, he pulverizes some notes, but the moments of insight and genuine beauty more than compensate. Just like Liszt himself, Pogorelich is a bit of a showman and does things to draw attention to himself. But in this piece it works! Fortissimos are indeed loud, and pianissimos are incredibly soft. This is an intense reading, bringing out all the emotion while also showing Pogorelich to be a masterful interpreter when he chooses to be. The sound is fine, though the sound of the piano itself is not the best in my opinion.

Brazilian pianist Arnaldo Cohen was unknown to me, but his 2003 Liszt Sonata on the BIS label is among the most satisfying renditions. Cohen benefits from outstanding BIS engineering, but the performance itself is also top drawer. Cohen takes nothing for granted and seems to interpret each section perfectly in terms of the ideal pacing, phrasing, dynamics, and tempos for each. As I’m listening, I kept thinking this can’t get any better, and it did. Cohen takes his time where needed and lets the music sink in during rhetorical passages, but he doesn’t hold back in the quick fingerwork passages either. It is an impressive balance, and Cohen’s overall vision for the work is compelling and feels right.

I have been a fan of the French pianist David Fray since I heard recordings of him playing Mozart and Bach. His 2006 recording of the Liszt Sonata on the ATMA label, when Fray was just 25, shows a remarkable maturity and integrity. The Andante sostenuto sections are especially beguiling, while his tone is bright and full. Again, like many of the great interpreters of this work, Fray nicely balances the lyrical and percussive elements and makes good judgments when it comes to pacing and dynamics. Fray possesses a uniquely noble and elegant tone, as well as the technical chops needed for Liszt. The ATMA recording quality is near perfection to my ears.

Also from 2006 is another scintillating account from yet another pianist unknown to me, the Greek pianist George-Emmanuel Lazaridis on the Linn label. Recorded at The Maltings at Snape (UK), one of my favorite recording venues, Lazardis’ account clocks in at 33:44 which is one of the slower accounts. But don’t let that fool you. While Lazardis does luxuriate in the best way in slower passages, he builds the tension superbly in transition to other more frenetic sections. Lazardis produces a full and wide tone (in the manner of Arrau), certainly helped by Linn’s fine engineering. What I really like is how Lazardis never loses touch with the musical line, not even in more demonic phrases. Lazardis tells a story with this performance, and thus it becomes greater than the sum of the notes. This is a wonderful find.

Argentine pianist Nelson Goerner has recorded the Liszt Sonata twice now, in 2007 on the Cascavelle label and again recently in 2023 for Alpha. Both are recommended, but if I had to choose one it would be the earlier one for greater spontaneity. Goerner has an intuitive sense of the drama inherent in this music, and the way he communicates the main themes reminds me of Arrau or Bolet. He chooses tempos wisely and draws nice contrasts between each section. Goerner is intelligent in the way he chooses when to bring his own flavor to the performance, and he does it in mostly subtle ways. His more recent recording is somewhat less emphatic, and perhaps more nuanced. The sound is also fuller and more balanced. But both recordings are remarkably similar in Goerner’s basic vision and approach, and even the timings are similar. In both recordings Goerner brings delicacy to the Andante sostenuto sections, and a lively spring to the fugato section following it.

Russian pianist Boris Berezovsky had made some interesting recordings over the years, some really outstanding and some rather pedestrian. This live recording from 2010 on the Mirare label definitely falls into the outstanding category. Quite the opposite of Lazardis, Berezovsky puts down one of the quickest accounts at a total timing of 25:25, but while that might imply he runs roughshod over some themes, that turns out not to be the case. Berezovsky does push ahead noticeably in some sections, but there is a confidence and vision that carries it along. Indeed, Berezovsky’s playing may rightly be called thrilling and it is clear he is enjoying the ride too. Berezovsky employs some admirable phrasing and dynamics which enhance the meaning for me at least, and give an impression of making more space for the music, even though he never slows down in the manner of Arrau or Lazardis. The fugato section after the Andante sostenuto is pointed and rhythmically tight, thrown off with a striking aplomb. The entire performance is to be relished, and while there is definitely a place for more relaxed performances, this is good stuff.

I appreciate the pianism of Hélène Grimaud, and although not every recording she makes is to everyone’s taste, I admire her bold approach and the detail she brings out. Her 2010 recording of Liszt’s Sonata for Deutsche Grammophon reveals an artist not content to just be bold, but she opts to focus on tonal color and phrasing more than power here, and the uniqueness of this approach pays dividends. Grimaud melds the various sections and themes into a greater unity better than most, and she brings sensitivity and mystery in her tone. She uses the pauses between notes so well too, and brings an almost three-dimensional quality to her playing where emotions come to life. Grimaud’s characteristic passion is never far away, but she also knows when to pull back. The acoustic is a bit over-reverberant, but nothing too distracting.

Almost any music the Canadian virtuoso pianist Marc-André Hamelin plays turns to gold, and his 2010 recording of the Sonata on Hyperion is no exception. If I had to choose another pianist that Hamelin reminds me of, it might be Krystian Zimerman in the sense that Hamelin exhibits extraordinary control partnered with a big sound and virtuosic mastery. This is a well considered, well paced, and finely inflected account with plenty of personality. If he doesn’t quite reach the heights of Arrau or Horowitz, he does inject some unique color and phrasing which are delightful. Hamelin also makes the most of the transitions and the louder sections, making his points emphatically but also musically. The sound from Hyperion is top shelf.

Ukrainian pianist Alexei Grynyuk was also new to me, but he certainly won’t be anymore. Grynyuk’s 2010 account of the Sonata on the Orchid label also finds its way to the top tier of recordings of this epic piano work. I read one review which was very critical of Grynyuk’s performance, saying it had no heart. I don’t know what performance that person was listening to, but it certainly wasn’t this one. Grynyuk’s virtuosic abilities are easily apparent, and in fact the faster runs of the Allegro energico and of the Presto-Prestissimo sections are as exciting as you will find. Furthermore Grynyuk produces a wonderfully pleasing tone, and he really knows how to communicate via dynamics and pacing. I never get the impression Grynyuk is playing to the crowd either, as his entire conception impresses me as genuine and personal while still being faithful to the score. The sound is ideal for this work.

German-Italian pianist Sophie Pacini has been on the scene for some time now (though she is still only 33), but her Sonata from 2012 on Avi Music is my favorite recording she has made. It is fairly well known that Pacini befriended Martha Argerich prior to this recording and Pacini shares some of her mentor’s approach. It is as though she consumes the Sonata whole, such is the ferocity she attacks the more extrovert passages. But a closer inspection shows that Pacini brings a notable thoughtfulness and discovery to the slower sections as well. One of the criticisms of Pacini early on was that she played works with small snippets in mind rather than as a unified whole. I don’t sense that at all here, indeed Pacini draws the listener in gradually and builds the story as she goes. It is true she is a more passionate, subjective sort of interpreter but that is no bad thing in Liszt. The sound is very good.

German pianist Joseph Moog first came to my attention with his 2015 album which included the Grieg and Moszkowski concertos on the Onyx label. But his 2019 Liszt Sonata also on Onyx is really something special. Moog takes us on quite a jaunt, and it is a thrill. This is not a reflective performance in the style of Arrau or Lazardis but rather takes the piece by the throat and never lets up. Okay that is a bit of an exaggeration, there are moments of quietude and lyricism, but even there it points to Moog’s incredible passage work and skills. Moreover Moog finds new ways to phrase things and draws pretty clear delineation between moods and personalities in the music. Meanwhile Moog also produces some sparkling technique, and seems to know just when to hit the accelerator. In summary, this is a very worthy addition to the vast Liszt Sonata catalog.

Honorable Mention

The differences between many of the recommended recordings above and those below in honorable mention are often slight and subjective.

Lou Kentner (APR 1948)

Alfred Brendel (Artemisia 1958)

Emil Gilels (Melodiya 1961)

Yvonne Loriod (Decca 1963)

Sviatoslav Richter (Philips/Universal 1965)

André Watts (Sony 1971)

Claudio Arrau (Doremi 1972)

Van Cliburn (RCA 1975)

Alicia de Larrocha (Decca 1976)

Vladimir Horowitz (Sony 1976)

Vlado Perlemuter (Nimbus 1979)

Shura Cherkassky (Nimbus 1984)

Cécile Ousset (Warner 1985)

Louis Lortie (Chandos 1986)

Maurizio Pollini (DG 1990)

Alfred Brendel (Philips/Universal 1991)

Elisabeth Leonskaja (Warner 1991)

Markus Groh (Avie 2006)

Polina Leschenko (Avanti 2007)

Kirill Gerstein (Myrios 2010)

François-Frédéric Guy (Zig Zag 2010)

Michael Korstick (CPO 2010)

Haiou Zhang (haenssler 2010)

Khatia Buniatishvili (Sony 2011)

Dénes Várjon (ECM 2012)

Boris Giltburg (QE 2013)

Angela Hewitt (Hyperion 2014)

Roger Muraro (Dolce Vita 2014)

Nicholas Angelich (Warner 2016)

Lucille Chung (Signum 2017)

Francesco Piemontesi (Pentatone 2021)

Benjamin Grosvenor (Decca 2021)

Whew! Okay I’m worn out. I may have missed some recordings, and if so send me a message.

But the list never stops. Join me next time when we cover another major solo piano work, Chopin’s dramatic Ballade no. 1. Thank you for hanging with me through Liszt!

_______________

Notes:

Bertagnolli, Paul, "Liszt's Teachers". In Cormac 2021, pp. 10–19.

Bloom, Peter (1998). The Life of Berlioz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521480914. OL 344098M.

Bonds, Mark Evan (2014). Absolute Music: The History of an Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press. OL 26883046M.

Botstein, Leon (17 October 2011). "What Makes Franz Liszt Still Important?". The Public Domain Review. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

Davison, Alan (Autumn 2006). "Franz Liszt and the Development of 19th-Century Pianism". The Musical Times. 147 (1896): 33–43. doi:10.2307/25434402. JSTOR 25434402.

Deaville, James, "The New German School". In Cormac 2021, pp. 48–57.

Friedheim, Philip (1962). "The Piano Transcriptions of Franz Liszt". Studies in Romanticism. 1 (2): 83–96. doi:10.2307/25599545. JSTOR 25599545.

Grey, Thomas S. (2001). "New German School". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40621.

Hilmes, Oliver (2016). Franz Liszt: Musician, Celebrity, Superstar. Translated by Spencer, Stewart. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21946-3. OL 26316088M.

Jost, Peter, ed. (2020). "Preface". Années de pèlerinage, Première Année – Suisse (PDF) (in English, German, and French). G. Henle Verlag. ISMN 979-0-2018-1490-2.

Ramann, Lina (1882). Franz Liszt, Artist and Man: 1811–1840. Translated by Cowdery, E. London: W. H. Allen & Co. OL 7103128M.

Rosen, Charles (23 February 2012). "The Super Power of Franz Liszt". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

Searle, Humphrey (1995). "Liszt, Franz". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 11. London: Macmillan. pp. 28–74. OL 18342085M.

Walker, Alan (1973). The Great Composers: Liszt. New York: T. Y. Crowell Co. ISBN 9780690496994. OL 21091256M.

Walker, Alan (1989). Franz Liszt: The Weimar years, 1848-1861. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801497216.

Warrack, John, "New German School". In Latham 2002, p. 834.

Whitelaw, Bryan A., "Paris". In Cormac 2021, pp. 20–28.

https://www.laphil.com/musicdb/pieces/5656/piano-sonata-in-b-minor

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_Sonata_in_B_minor_(Liszt)

Happy new year John!

It seems that the best interpretation of this piece have been made when the interpreters were younger. Unlike Beethoven or Schubert.

Anyway, you know that I always have fun proposing something that isn't there :-)

Try Sergio Fiorentino on Piano Classics APR (hard to find).