Building a Collection #68

Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville)

By Gioachino Rossini

________________

A warm welcome back to all subscribers, and hello to any new readers or subscribers out there. We have arrived at the first entry on our survey by the Italian composer Gioachino Rossini and probably his most well-known opera Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville) in spot #68. A famous overture, sparkling melodies and arias, and a comical libretto have made this a crowd favorite for many decades.

Gioachino Rossini

Gioachino Rossini (1792 - 1868) was an only child from a musical family in Pesaro, Italy and by the age of 12 he was composing. He attended music school at the Liceo in Bologna, and his first opera was staged in Venice when he was just 18 years of age. Between the years of 1810-1823 Rossini wrote no less than 34 operas which were performed across Italy. Rossini composed some music other than operas, but today he is most well-known for his opera buffo works, otherwise known as Italian comic opera.

During his period of great productivity, Rossini created his most well-known and popular comic operas including L’Italiana in Algeri (The Italian Girl in Algiers), Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville), and La Cenerentola (Cinderella). Rossini would also compose serious operas such as Tancredi, Semiramide, Otello, Le comte Ory, Le siege de Corinthe, Il viaggio a Reims, Mosè in Egitto, and his final opera Guillaume Tell (William Tell, from which comes the famous William Tell Overture, immortalized for being used as the theme for the Lone Ranger TV series in the 1950s).

It has long been thought Rossini was greatly inspired when he heard the music of Mozart and Haydn. Indeed, his music has more in common with the classical era masters than the later Italian opera composers Puccini and Verdi. Rossini was a very quick learner and was composing from a young age. After writing several operas while still in his teens, he was persuaded to move to Venice when he turned 18 to pursue opera composing full-time. At that time, Venice was known to be the center of the opera world.

Rossini became increasingly well-known through writing operas for performance in Rome, Milan, and Venice. The success he had with Tancredi (1813) made him internationally known as the opera was performed in London and New York. A few years later, Rossini moved to Naples and took up a post as director for the royal theatres. Naples had been an operatic capital previously, and native sons such as Domenico Cimarosa and Giovanni Paisiello were still celebrated for their operas. Rossini was seen as a bit of an outsider, but after the success of his operas Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra and L'italiana in Algeri he was fully accepted by the Neapolitan public. While most of his operas were composed for production in Naples, importantly in 1816 he wrote Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville) for Teatro Argentina in Rome. Il barbiere di Siviglia would become Rossini’s most enduringly popular opera.

It is noteworthy that Rossini often recycled his own music for “new” productions and would sometimes adapt melodies and tunes to fit different lyrics. You may notice that some of the music for the incredibly difficult tenor aria Cessa di piu resistere (in Act II of The Barber of Seville) was later also used by Rossini for the mezzo aria Nacqui all’affanno…non piu mesta (in Act II of La Cenerentola). Portions of specific overtures were also reused in other works. This was not so uncommon in Rossini’s time.

In the early 1820s Rossini became disillusioned with Naples and moved to Vienna where he was welcomed like a conquering hero. Several of his operas were quickly produced in Vienna to rapturous reception. During this time Rossini was able to meet Beethoven, and Beethoven expressed admiration for Rossini’s work, and in particular the comic operas. Although Rossini would spend time in London, the reception he received was chillier, and from 1824 he retreated to Paris where he felt much more at home. It was in Paris where Rossini began to gain weight to the point where he cut quite a rotund figure. He composed some operas after being commissioned by the French government, eventually writing four operas in the French language (with Le comte Ory being the lone comic opera in French). What would turn out to be his final opera, Guillaume Tell, was staged in 1832 and was very well received. Rossini’s reputation became even greater, and he was revered in both France and Italy. While not producing any more operas, Rossini composed his Stabat Mater (1841) and his Petite messe solennelle (1863).

One of the most extraordinary facts about Rossini is his retirement from composing when he was only in his 30s, and that he didn’t write any operas for the last 40 years of his life. It is somewhat of a mystery why Rossini stopped composing after being so prolific and having such great success. Some scholars theorize it may have been due to poor health or achieving fame and wealth to a level he didn’t need to work, or perhaps the field of opera was undergoing some major shifts at that time. We know Rossini suffered from gonorrhoea as well as depression after the death of his mother, some even claiming he had bipolar disorder. In any case, his withdrawal from composing prompted the critic Francis Toye to comment in his 1934 study of Rossini: “Is there any other artist who thus deliberately, in the very prime of life, renounced that form of artistic production which had made him famous throughout the civilized world?”

Rossini’s legacy has been somewhat diminished by the changes in the music world, and particularly opera, over the years. At some point Rossini’s operas were criticized as being unserious and too repetitive. However, composers such as Verdi, Respighi, Offenbach, Adam, Auber, and Britten all drew inspiration from Rossini, and in the 20th century there developed a renewed appreciation for his body of work.

Il barbiere di Siviglia

The Barber of Seville is an opera buffa in two acts composed by Gioachino Rossini with an Italian libretto by Cesare Sterbini. The libretto was based on Pierre Beaumarchais's French Comedy The Barber of Seville (1775). The première (under the title Almaviva) took place on February 20th, 1816, at the Teatro Argentina, in Rome. Some consider it to be the greatest comic opera ever composed.

Beaumarchais wrote three plays which all revolve around the character of Figaro, and 30 years prior to Rossini’s opera Mozart had used the second play as the basis for his blockbuster opera Il Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro). Rossini uses the first play in the trilogy. Incredibly, Rossini composed the music for The Barber of Seville in under three weeks, although the famous overture actually recycles music from two earlier operas and contains no thematic material from the opera itself. Another prominent Italian composer of the day, Giovanni Paisiello, had already written an opera based on the play The Barber of Seville, although today it is nearly forgotten, and Rossini’s tuneful masterpiece lives on.

The premiere of the opera was a disaster, mostly owing to the disruptions caused by the followers of Paisiello showing up in order to purposely turn the audience against Rossini’s version. Thus, it was reported there were incidents of hissing and jeering. Nonetheless when the opera had its second performance, it was received as a rousing success. From there the opera moved on to London eventually and then to America, all the while becoming more popular with audiences.

The synopsis of the story is below, as outlined by The Metropolitan Opera:

ACT I

Seville. Count Almaviva comes in disguise as a poor student named Lindoro to the house of Dr. Bartolo and serenades Rosina, whom Bartolo keeps confined to the house. Figaro the barber, who knows all the town’s secrets and scandals, explains to Almaviva that Rosina is Bartolo’s ward, not his daughter, and that the doctor intends to marry her. Figaro devises a plan: The Count will disguise himself as a drunken soldier with orders to be quartered at Bartolo’s house, so that he may gain access to Rosina. Almaviva is excited, and Figaro looks forward to a nice cash pay-off.

Rosina reflects on the voice that has enchanted her and resolves to use her considerable wiles to meet the man to whom it belongs. Bartolo appears with Rosina’s music master, Don Basilio. Basilio warns Bartolo that Count Almaviva, who has made known his admiration for Rosina, has been seen in Seville. Bartolo decides to marry Rosina immediately. Basilio suggests slander as the most effective means of getting rid of Almaviva. Figaro, who has overheard the plot, warns Rosina and promises to deliver a note from her to Lindoro. Bartolo suspects that Rosina has indeed written a letter, but she outwits him at every turn. Bartolo warns her not to trifle with him.

Almaviva arrives, creating a ruckus in his disguise as a drunken soldier, and secretly passes Rosina his own note. Bartolo is infuriated by the stranger’s behavior and noisily claims that he has an official exemption from billeting soldiers. Figaro announces that a crowd has gathered in the street, curious about the argument they hear coming from inside the house. The civil guard bursts in to arrest Almaviva, but when he secretly reveals his identity to the captain, he is instantly released. Everyone except Figaro is amazed by this turn of events.

ACT II

Bartolo suspects that the “soldier” was a spy planted by Almaviva. The Count returns, this time disguised as Don Alonso, a music teacher and student of Don Basilio, to give Rosina her singing lesson in place of Basilio, who, he says, is ill at home. “Don Alonso” then tells Bartolo that when visiting Almaviva at his inn, he found a letter from Rosina. He offers to tell her that it was given to him by another woman, seemingly to prove that Lindoro is toying with Rosina on Almaviva’s behalf. This convinces Bartolo that “Don Alonso” is indeed a student of the scheming Basilio, and he allows him to give Rosina her lesson. With Bartolo dozing off, Almaviva and Rosina declare their love.

Figaro arrives to give Bartolo his shave and manages to snatch the key that opens the doors to Rosina’s balcony. Suddenly, Basilio shows up looking perfectly healthy. Almaviva, Rosina, and Figaro convince him with a quick bribe that he is in fact ill and must go home at once. While Bartolo gets his shave, Almaviva plots with Rosina to meet at her balcony that night so that they can elope. But Bartolo overhears them and, realizing he has been tricked again, flies into a rage. Everyone disperses.

The maid Berta comments on the crazy household. Bartolo summons Basilio, telling him to bring a notary, so Bartolo can marry Rosina that very night. Bartolo then shows Rosina her letter to Lindoro, as proof that her student is in league with Almaviva. Heartbroken and convinced that she has been deceived, Rosina agrees to marry Bartolo.

A thunderstorm passes. Figaro and the count climb a ladder to Rosina’s balcony and let themselves in with the key. Rosina appears and confronts Lindoro, who finally reveals his true identity as Almaviva. Basilio shows up with the notary. Bribed and threatened, he agrees to be a witness to the marriage of Rosina and Almaviva. Bartolo arrives with soldiers, but it is too late. He accepts that he has been beaten, and Figaro, Rosina, and the Count celebrate their good fortune.

The primary roles in the opera are as follows:

Count Almaviva - tenor

Bartolo, doctor of medicine, Rosina's guardian - bass

Rosina, rich pupil in Bartolo's house - contralto, mezzo-soprano, or soprano

Figaro, barber - baritone

Basilio, Rosina's music teacher - bass

The role of Rosina was originally written for contralto voice. However, down through the years it has also been sung by sopranos at a higher pitch or mezzo-sopranos at a slightly lower pitch and so when we get to the recordings below you will notice both sopranos and mezzo-sopranos in the role. There are very few true contraltos out there that can sing the role. Some have complained about the adaptation of the part for sopranos, but there is also evidence that Rossini himself made such changes at times. In any case, the characterization of the role does change a bit when sung by a soprano versus a mezzo.

Something else you will notice with a lot of Rossini voices is the use of florid, ostentatious embellishments in some of the big arias. This is particularly true of Rosina’s Act I aria Una voce poco fa. On one occasion Rossini himself, after hearing a singer perform a greatly embellished version of the aria, asked her: "Very nice, my dear, and who wrote the piece you have just performed?” If you listen to Maria Callas in her famous recording, or when she taught her master classes to young singers, she would insist on keeping the vocal theatrics to a minimum unless it was tastefully done. But others have insisted on using it as a showstopper where they belt out all their vocal tricks. I will let you decide which approach you prefer. This is also true of the baritone and tenor arias, though to a lesser extent.

Count Almaviva is given a few difficult arias to sing, none more so than the feared Cessa di piu resistere which occurs near the end of Act II. Indeed, over the decades the aria has often been cut entirely due to the endurance and technical prowess it requires to sing it correctly and effectively. You will notice it is completely cut from some recordings. But when it is included, and done well, it is one of the most thrilling moments in all of opera.

Those of us of a certain age will also recall with a smile that our introduction to Figaro’s famous aria Largo al factotum in Act I was through Daffy Duck on Looney Tunes, and that the overture was used by Warner Brothers in 1950 for the hilarious Rabbit of Seville clip starring Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd.

Recommended Recordings

We see fewer and fewer contemporary recordings of standard opera fare, and the golden age of opera recordings is long past. Some of the best recordings of The Barber of Seville, similar to many other operas, date from the 1950s or 1960s. There have been some very good ones more recently but finding a cast of singers that can do all the major roles justice is a tall order.

Italian conductor Alberto Erede was particularly known for his interpretations of Italian opera, but he conducted all sorts of opera all over the world. His 1956 recording of The Barber of Seville, originally made for Decca (now on Urania), shows his special feeling for Rossini. Along with the Orchestra e Coro de Maggio Musicale Fiorentino (Florence), the cast includes baritone Ettore Bastianini as Figaro, mezzo Giulietta Simionato as Rosina, Don Bartolo, bass Fernando Corena as Bartolo, bass Cesare Siepi as Basilio, and tenor Alvino Misciano as Count Almaviva. Bastianini is simply superb, bringing one of the most gorgeous baritone voices ever to Figaro. Misciano as Almaviva lacks some power and his runs are not immaculate, but he is touching and creamy of tone, never pushing too hard, and is a fine vocal actor. Misciano is perhaps better known as the man that “discovered” Luciano Pavarotti and became his mentor. But he does just fine here. Simionato as Rosina gives me pause in the sense that she had a heavier and slightly deeper, more chesty voice. Coloratura roles which demanded ornamentation and quicker runs of notes were not really her thing. Despite this reservation, she has plenty of heft and is a strong vocal actress. Corena and Siepi are both among the finest on record in their respective roles and are enjoyable in their roles. The sound is good with a bit of harshness on top as well as a bit of background noise, but nothing bothersome.

The legendary soprano Maria Callas is one of my favorite sopranos ever, not for the beauty of her voice (because her voice wasn’t beautiful), but because she knew how to use it. The 1957 recording on EMI/Warner which features her as Rosina, Tito Gobbi as Figaro, and Luigi Alva as Count Almaviva is with the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Alceo Galliera. About a year before this recording, Callas made her debut as Rosina in a production where she was widely panned as Rosina. But by the time this recording was made, she had learned the role much better and knew how to sing the role. Callas is not a natural Rosina, and for me the piercing quality of her voice detracts slightly from my enjoyment of the recording. But her performances of Una voce poco fa and Dunque io son are well characterized and well sung. Tito Gobbi is a believable and effective Figaro, though I can’t get the role of Scarpia (from Puccini’s Tosca) out of my mind when I hear his voice. Luigi Alva became very associated with the role of Almamiva, and he appears on other recordings of the opera as well. While his voice has sweetness and he would have been known as a “tenor di grazia” for the light and agile quality of his voice, he does not have enough agility for Cessa di piu resistere and thus the aria is scrapped for this recording. The articulation of his notes is also not very clear, he tends to slur the notes together. Nevertheless, Alva is a good vocal actor and knows how to bring out the comic element. Galliera and the Philharmonia acquit themselves quite well, and the chorus is superb. The sound is good for its time. While not an essential recording, this remains a classic and brings consistent pleasure.

Just a year later in 1958 we were given another splendid recording from The Metropolitan Opera in New York with Erich Leinsdorf conducting, a recording which was released on the RCA Living Stereo label. Leinsdorf is joined by soprano Roberta Peters as Rosina, baritone Robert Merrill as Figaro, tenor Cesare Valletti, bass Fernando Corena as Bartolo, and Giorgio Tozzi as Basilio. One is immediately struck by the immediacy and clarity of the sound as well as the energy and engagement of the cast. Leinsdorf was a wonderful opera conductor, and while he was known for his Wagner and Verdi, his Mozart and Rossini were just as good. Roberta Peters is nothing short of spectacular in her arias, and even if she sings many embellishments which are not in the score, hers is a thrilling Rosina to be treasured. It is easy to see why she was a celebrated Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute. Robert Merrill is a reliable and full-throated Figaro, even if he is less than subtle at times. Cesare Valletti is an excellent Almaviva, far preferable to Luigi Alva in my book. His ornamentation and ability to sing most of the notes in the score is admirable and his tone is unfailingly sweet and appealing. This is one of the finest portrayals of Almaviva on record. Full credit to Leinsdorf for letting us actually hear the guitar in the Act I Ecco ridente in cielo. Valletti’s Cessa di piu resistere is a noble and worthy effort, even if Leinsdorf has to slow things down to help him get through it. Corena and Tozzi are both excellent as well, and the Met Opera Chorus is outstanding. The finale Di si felice innesto is fantastic. This may be the finest Barber on record, but you the listener can decide for yourself. For me, it is probably the one I will return to most often.

The 1965 Decca production from the Orchestra and Coro del Teatro di San Carlo di Napoli (Naples) under the direction of Silvio Varviso remains one of my favorites. It features the lovely mezzo-soprano Teresa Berganza as Rosina, baritone Manuel Ausensi as Figaro, tenor Ugo Benelli as Count Almaviva, the great Nicolai Ghiaurov as Basilio, and Fernando Corena once again as Bartolo. This is as enjoyable and idiomatic recording as you will find, the comedy and the wink of the eye never far away. There is a warmth and beauty to the entire production, enhanced by Decca’s wonderful sound. Ugo Benelli’s Almaviva is not quite as distinct as Valletti’s (above), but it is still well above average. His vibrato is faster, the tone a bit nasal, and he is slightly off pitch a few times. Having said that, he does a very fine job with Cessa di piu resistere. I quite like Ausensi’s Largo al factotum, his tone reminding me of Tito Gobbi. Ausensi and Benelli blend very well on All’idea di quel metallo, one of my favorite numbers in the opera. Teresa Berganza is classy, expressive, and able to lighten and darken her voice at will. This is one of the satisfying Rosinas on record, and she does it without resorting to excessive fireworks (except at about 2’05” into Una voce poco fa). I find her voice ideal for Rosina, and the performance sparkles. The other principals are among the best as well. I would be most happy if this was the only Barber I owned.

Some will take issue that my most recent recording on the recommended list is from 32 years ago! But such is the state of opera recordings these days. The last recommended recording on the list is from 1992 on the Naxos label with Will Humburg conducting the Failoni Chamber Orchestra (Budapest) and the Hungarian Radio Chorus with soloists tenor Ramon Vargas as Count Almaviva, baritone Roberto Serville as Figaro, mezzo Sonia Ganassi as Rosina, baritone Angelo Romero as Bartolo, and bass Franco Grandis as Basilio. I saw both Ganassi and Vargas in a production of Barber in Rome in January 1992, only months before this recording. The production was Ganassi’s debut in the role of Rosina at the age of 26. Serville and Grandis also performed in that production, though not on the night I attended. On this recording Vargas is as good as any Almaviva, and while he may not be a true “tenor di grazia”, he navigates all the notes and dynamics very well on Ecco ridente in cielo and with a full tone. While Vargas is not completely secure on Cessa di piu resistere and he makes a few edits, it is still a splendid performance of this most difficult aria, and he hits an incredibly high penultimate note. Ganassi has a somewhat husky voice, certainly comfortable in the contralto range, and her top end is substantial as well. Una voce poco fa is a bit too reticent and restrained, but upon further listenings I have come to appreciate Ganassi’s approach. Despite the hint of matronlyness in her voice, this is a vivid and engaging characterization. I really like Serville as Figaro, his voice is full and resonant, and he has great range. The duet All’idea di quel metallo with Vargas is among the best on record, both singers maintaining a light and playful sense throughout. Basilio’s arias La calunnia and is delivered with honeyed tone by Franco Grandis, and he reminds me of the great Kurt Moll (high praise indeed). Bartolo’s aria A un dottor della mia sorte is a bit more variable from Romero, but still perfectly fine. One thing I could take or leave is how they chose to use voices, instruments, and background noises to mimic a true stage presentation of the opera. It is subtle, so I didn’t find it bothersome. But it is a little bit odd. The Failoni Chamber Orchestra is terrific, as are the Hungarian Radio Chorus, and Humburg leads a brisk but never rushed performance which is light on its feet and dramatic. Highly enjoyable.

Honorable Mention Recordings

Because there are some very fine performances of individual roles in the recordings below, I have left some comments next to some of the versions. Again, these are all worthy accounts but for me personally just marginally miss the mark in one way or another.

The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus / DiStefano / Valdengo / Pons / Erede (Sony 1950)

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Glyndebourne Festival Chorus / Alva / Bruscantini / de los Angeles (EMI/Warner 1962) - this recording is a classic and worth hearing for sure. De los Angeles is a lovely if somewhat under-characterized Rosina, but as I’ve said Alva is not my favorite Almaviva and some tempos from Gui seem a bit too slow.

London Symphony Orchestra and Ambrosian Chorus / Alva / Prey / Berganza / Abbado (DG 1972) - the favorite recording for many, I find Abbado too laid back and even uninterested at times. As I said, I am not a fan of Alva’s Almaviva, and Prey takes a sledgehammer to Figaro by lacking subtlety and humor. Berganza is terrific as usual, but certainly not better than her 1965 recording with Varviso above. Abbado recorded the opera again in 1991 with Placido Domingo and Kathleen Battle, but I would avoid that one.

Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields and Ambrosian Singers / Araiza / Allen / Baltsa / Marriner (Decca 1982) - a lost opportunity by Marriner. Francisco Araiza and Thomas Allen both make excellent contributions (Allen’s Largo al factotum is terrific and Araiza’s Cessa di piu resistere is more than adequate). Baltsa is good as well. The cast are let down by a lackluster and frankly boring reading by Marriner that frankly sucks the life out of the music and text.

Orchestra e Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna / Nucci / Matteuzzi / Bartoli / Patanè (Decca 1988) - Bartoli alone might be enough reason to acquire this set, she is scintillating as she was in the La Cenerentola recording from around the same time. Matteuzzi’s Almaviva runs into issues in Ecco ridente, and he wisely doesn’t attempt Cessa di piu. I am sorry to say I’ve never warmed to Nucci’s voice, it is not quite right for Figaro in my opinion. The elderly Patanè is too relaxed for my taste.

Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne et Chorus of the Grand Theatre of Geneva / Hagegård / Giménez / Larmore / López Cobos (Warner 1993) - A very good set which I remember loving when it was first released. Giménez is a quite legitimate Almamiva, agile, tender, and powerful when needed. I really liked Larmore at this young point in her career, her mezzo is warm and lustrous. Listening to her Una voce poco fa again now, I find her somewhat too mannered and perhaps trying too hard. But it is still a remarkable voice. I remember liking Hagegård’s Figaro more when I first heard it years ago. He is perfectly fine, but the overall characterization is a bit lacking in comparison to some of the other great Figaros on record. The orchestra also seems somewhat recessed to me. In any case, this is worth hearing.

Recommended Videos

Some will choose the film made with Abbado in Milan which goes along with the same cast from the DG recording listed above, and the film has garnered many wonderful reviews. For me it has the same drawbacks as the audio recording does.

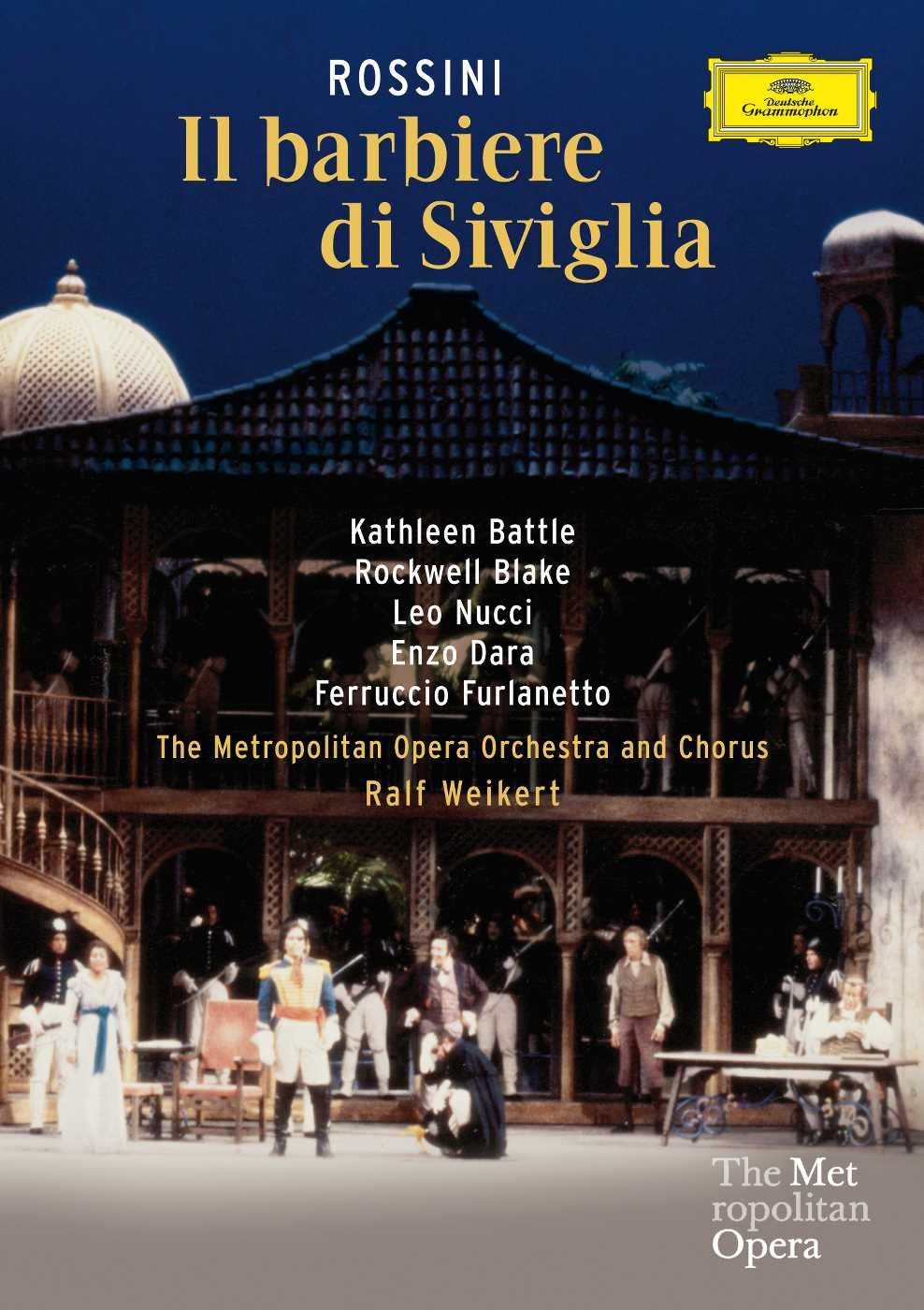

The 1989 Deutsche Grammophon video from The Metropolitan Opera under the direction of Ralf Weikert features a sparkling Rosina in Kathleen Battle partnered with the stupendous Almaviva of Rockwell Blake. Even though I could pass on Leo Nucci’s Figaro again, Enzo Dara’s Bartolo is a priceless performance. The rest of the cast is above average. Battle is fresher and more imaginative than she is later for Abbado, and she follows in Roberta Peters footsteps in singing Rosina as a coloratura soprano with plenty of embellishment. Battle was infamous for being a difficult person to deal with for opera companies, but what an angelic voice! Some have complained about a bit of a beat in Blake’s voice, but I don’t detect it and if it is there it doesn’t bother me in the least. His Cessa di piu resistere is incredible in my opinion. So, if you are okay with Nucci as Figaro, this is a fun performance.

The 2009 Covent Garden production of Barber on Virgin led by Antonio Pappano with the Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House with a starry cast including soprano Joyce DiDonato as Rosina, tenor Juan Diego Flórez as Almaviva, baritone Pietro Spagnoli as Figaro, baritone Alessandro Corbelli as Bartolo, and bass Ferruccio Furlanetto as Basilio. Flórez is sensational, easily one of the best Almavivas ever with a plangent and agile coloratura tenor voice. Similarly, DiDonato is superb in a confident and virtuosic performance (despite breaking a bone in her foot shortly before the production began and being relegated to a wheelchair in performances). The rest of the Italian cast is completely idiomatic and comic in their delivery. Pappano is an outstanding opera conductor and knows this music inside and out. A triumph, and you would be hard pressed to find a better video version of the opera.

Thank you once again for joining me on this journey! I hope you find some recordings of this great comic opera that you enjoy. Join me next time when we change gears to discuss Franz Liszt’s Sonata in B minor, number #69 on our list. See you then!

______________

Notes:

Casaglia, Gherardo (2005). "Il barbiere di Siviglia, 20 February 1816". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

Gossett, Philip (2001). "Rossini, Gioachino (Antonio)". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.23901.

Gossett, Philip; Brauner, Patricia (1997). "Rossini". In Holden, Amanda (ed.). The Penguin Opera Guide. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-051385-1.

Kendall, Alan (1992). Gioacchino Rossini: The Reluctant Hero. London: Victor Gollancz. ISBN 978-0-575-05178-2.

Osborne, Richard (1992). "The Barber of Seville". In Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Vol. 1. London: Macmillan. ISBN 1-56159-228-5.

Osborne, Richard (2007). Rossini (second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518129-6.

Servadio, Gaia (2003). Rossini. London: Constable. ISBN 978-1-84119-478-3.

Toye, Francis (1947) [1934]. Rossini: A Study in Tragi-Comedy. New York: Knopf. OCLC 474108196.

Weinstock, Herbert (1968). Rossini: A Biography. New York: Knopf. OCLC 192614.

Synopsis found online at https://www.metopera.org/discover/synopses/il-barbiere-di-siviglia/.

![Gioachino Rossini - Il barbiere di Siviglia (Royal Opera House, Covent Garden 2008) [DVD] [2010 ... Gioachino Rossini - Il barbiere di Siviglia (Royal Opera House, Covent Garden 2008) [DVD] [2010 ...](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!D0LB!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8bd07be6-aade-4ed3-9560-57989c1c3297_768x1024.jpeg)