Building a Collection #65

Violin Concerto in D, Op. 61

By Ludwig van Beethoven

________________

“To play a wrong note is insignificant; to play without passion is inexcusable.”

― Ludwig van Beethoven

Welcome back! With #65 on our list, we encounter Beethoven for the seventh time, this time with his only violin concerto, his Violin Concerto in D major. Let me say at the outset, I am fully aware this post has taken me longer. My obsessive “completist” tendencies don’t do me any favors at times, but that is how it is. I want to thank you for your patience.

Ludwig van Beethoven

At this point in my posts I generally give a biographical sketch of the composer, but since we have covered a lot of Beethoven in previous posts I will direct you elsewhere for this information in order to save space. The books listed below are good resources:

Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph by Jan Swafford (2014)

Beethoven by Maynard Solomon (1979)

Beethoven: The Man Revealed by John Suchet (2013)

Beethoven: A Life by Jan Caeyers (2020)

You may also want to refer to one of my previous posts which gives some facts about Beethoven in a bulleted format:

https://classicalguy.substack.com/p/23-beethoven-complete-music-for-cello

Violin Concerto in D major

In the years between writing the Symphony no. 3 “Eroica” which saw the composer using a new musical language (1804) and the premiere of his revolutionary Symphony no. 5 (1808), Beethoven struggled mightily with writing his only opera Fidelio. At some point he put aside Fidelio and completed a series of works including his Symphony no. 4, his Piano Concerto no. 4, and his Violin Concerto. These works are characterized by a more lyrical and less “heroic” style, which can very much be heard in the Violin Concerto. The concerto is more broad and spacious, seems less concerned with big gestures or virtuosity, and focuses on melody and the work’s overall superstructure. This was not as much a change of approach for Beethoven as it was the reemergence of this facet of the composer’s genius. Indeed Beethoven was working on the Violin Concerto at the same time as the Fifth Symphony, two works which show different sides of the great composer.

Beethoven wrote the concerto for the young violin prodigy Franz Clement, and so there is some speculation he wrote the concerto in a more lyrical, pastoral style in order to highlight the particular abilities of Clement. Like many prodigies of the day, Clement was toured around Europe by his father from the age of 7 playing in front of royalty and the public. Clement was a phenomenal talent who also played piano and had the incredible ability to sight read music and immediately play entire works from memory. Program annotator Marc Mandel wrote the premiere was given on December 23, 1806 with Clement reportedly playing his own work midway through the performance, holding the violin upside down!

Beethoven met with Muzio Clementi (pianist and publisher) in 1807 with Clementi trying to secure the rights to publish several of Beethoven’s recent compositions including the Violin Concerto. While Beethoven agreed, at the same time he was also shopping his works to other publishers and eventually had it published by the Bureau des Arts et d’Industrie in Vienna where the concerto was published in 1808, almost two years before Clementi published it in 1810. As part of Clementi’s negotiations he convinced Beethoven to adapt the Violin Concerto for piano as well, and so it happens there is a much less popular and less effective version for piano.

In any case, the Violin Concerto was not especially well-received as some critics thought it was overly repetitious and rather bland. It took some years for the concerto to be played more often, mostly only after the young virtuoso Joseph Joachim played it in 1844 with Mendelssohn conducting. Joachim took the liberty of composing his own cadenzas for the concerto (remember a cadenza is a virtuoso solo passage inserted into a movement in a concerto or other work, typically near the end), and while Joachim’s cadenzas are still used sometimes, today there are literally dozens of cadenzas written by different violinists and composers to choose from, with those from the famous violinist Fritz Kreisler being more frequently heard. Audiences gradually became very fond of the concerto, and of course it is one of the most often played and recorded violin concertos today.

But back to the work’s first soloist, Franz Clement. Clement was known for his deep expressiveness, elegance, and graceful playing, and thus it is not surprising the concerto is full of phrases which demand tenderness and subtlety. This is not to say the concerto doesn’t require a high degree of skill as well, notice the very exposed high notes in both the first and second movements. There are also several passages of trills the soloist must negotiate. But virtuosity alone is not enough in this concerto, the soloist must also possess a wealth of expressiveness and the ability to turn a phrase and make melodies sing.

The concerto is in three traditional movements as follows:

Allegro ma non troppo

Larghetto

Rondo. Allegro

I will leave it to the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s program annotator Marc Mandel to describe each movement:

“An appreciation of the first movement’s length, flow, and musical argument is tied to an awareness of the individual thematic materials. It begins with one of the most novel strokes in all of music: four isolated quarter-notes on the drum usher in the opening theme, the first phrase sounding dolce in the winds and offering as much melody in the space of eight measures as one might wish. The length of the movement grows from its duality of character: on the one hand we have those rhythmic drumbeats, which provide a sense of pulse and of an occasionally martial atmosphere, on the other the tuneful, melodic flow of the thematic ideas, against which the drumbeat figure can stand in dark relief.

The slow movement, in which the flute and trumpets are silent, is a contemplative set of variations on an almost motionless theme first stated by muted strings. The solo violinist adds tender commentary in the first variation (the theme beginning in the horns, then taken by the clarinet), and then in the second, with the theme entrusted to solo bassoon. Now the strings have a restatement, with punctuation from the winds, and then the soloist reenters to reflect upon and reinterpret what has been heard, the solo violin’s full- and upper-registral tone sounding brightly over the orchestral string accompaniment. Yet another variation is shared by soloist and plucked strings, but when the horns suggest still another beginning, the strings, now unmuted and forte, refute the notion. The soloist responds with a trill and improvises a bridge into the closing rondo.

By way of contrast, the music of this finale is mainly down-to-earth and humorous; among its happy touches are the outdoorsy fanfares that connect the two main themes and, just before the return of these fanfares later in the movement, the only pizzicato notes asked of the soloist in the course of the entire concerto. These fanfares also serve energetically to introduce a cadenza, after which another extended trill brings in a quiet restatement of the rondo theme in an extraordinarily distant key (A-flat) and then the brilliant and boisterous final pages, the solo violinist keeping pace with the orchestra to the very end.”

The Essential Recording

With so many outstanding recordings of this warhorse out there, I am going out on a limb in a significant way to identify only one essential recording. So I remind the reader that, as always, “essential” is still subjective. Having said that, this recording is essential in my book.

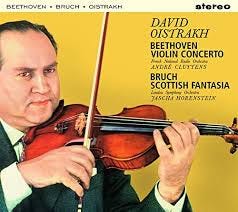

The 1958 recording by Ukrainian-born Soviet violinist David Oistrakh on EMI/Warner with Belgian-French conductor André Cluytens and the Orchestre National de France holds a special place in my heart. This is a traditional, relatively “old school” reading so don’t expect fleet tempos or period instrument manners. The reasons this classic rises to the essential level are three-fold. First, David Oistrakh was one of the finest interpreters of this concerto (along with many others of course) and he gets inside the sentimental and emotional aspects of the score more than almost anyone else. He knows perfectly how to shape phrases, when to press ahead and when to indulge a bit (and this concerto rewards indulgence more than most and is tailor made for Oistrakh’s temperament). Listen to the cadenza at the end of the finale! Oh my. I truly believe his warm, rich, creamy, and burnished tone has never been heard to better effect than on this record. The second reason is the outstandingly full and resonant sound engineering from EMI and the naturally generous acoustic of the Salle Wagram in Paris. Some say the sound is too forward and grating, but I don’t detect that at all. The final reason is the alert and vital conducting of Cluytens, who was one of the finest Beethoven conductors of his day and has an underrated legacy. Oistrakh even has another recording on the recommended list (see below), but this one is a cut above.

Recommended Recordings

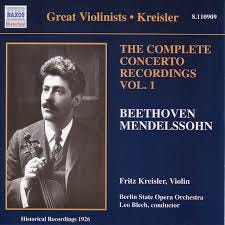

Legendary Austrian-American violinist Fritz Kreisler was a huge advocate of the Beethoven Violin Concerto and made two of the earliest recordings of the work. The first is from 1926 with the Staatskapelle Berlin and conductor Leo Blech on HMV/EMI/Warner, and the second is from 1936 with John Barbirolli and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the version I heard is on Biddulph. The first finds Kreisler in better technical form, the second one has better sound which you might expect. If only they could merge the two recordings! In both cases the orchestral accompaniment is of secondary importance to Kreisler’s solo work. Blech and the Berlin orchestra are scrappy and in quite compromised sound on the earlier one, but Kreisler rises above it with playing that is refined, lively, direct, and clear. On both recordings you will hear Kreisler employ sliding into notes and generous portamento which fell out of style later, but which at the time were quite normal and creative even if not in the score. Kreisler was a significant influence on later violinists, and we also have him to thank for the most popular and most common set of cadenzas used for this concerto.

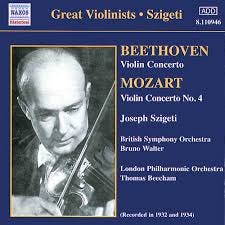

The great Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti was a child prodigy, and became an aristocrat of the violin, playing and teaching all over the world. Although he recorded the Beethoven Violin Concerto at least three times, it is his first outing with the British Symphony Orchestra under Bruno Walter (on the Naxos label) that shows him at his finest. Szigeti, known as the “musician’s musician” was a scholar and teacher as well, and abhorred showmanship or virtuosity for its own sake. Later in his career arthritis set in which began to impact him on his 1947 recording with Walter and was even more evident on his 1961 recording with Dorati. In this 1932 recording we are able to hear Szigeti in his glory, even with the sonic limitations. The violin part in particular is in decent sound, although the orchestra sounds distant and indistinct. But if you focus your attention on Szigeti’s solo, what you will hear is something special.

Fast forward to the great Jascha Heifetz. In my view Heifetz made two recordings of the concerto which are both recommended. The first is from 1944 with Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra (currently available on Naxos and streaming services), and the second is from 1955 with Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra on RCA/Sony. Heifetz had a sort of dispassionate, rational style which, despite not being my personal favorite, has a substantial appeal in Beethoven (more so than in Brahms and Tchaikovsky, in my humble opinion). Partnering with Toscanini, Heifetz delivers an arid, classically influenced, and completely refined performance which pleases due to its directness and clarity. There is a simplicity and austerity which is its own reward, really the opposite of any indulgence. The sound from 1944 is somewhat boxy being from the studio, but perfectly fine. The later recording with Munch in Boston is in fuller and richer sound, but more than that Heifetz has a more passionate and flexible partner in Munch. Heifetz’s approach hasn’t changed much, but I do detect more warmth and humanity. While perhaps marginally less technically immaculate, there is more of a sense of adventure and sheer joy. Both recordings are among my favorites Heifetz ever made, and both should be heard.

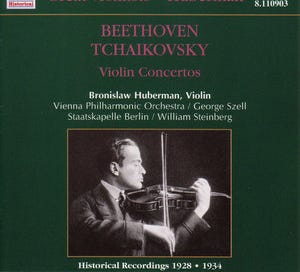

My personal favorite of the historical recordings of this concerto is by Polish violinist Bronisław Huberman with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra under a young George Szell, available on the APR label (and others including Pristine which is the finest remastering). Recorded in Vienna in 1934, this recording has a long reputation as a classic of the gramophone and it deserves it. Huberman, like Kreisler, was essentially a nineteenth-century violinist in manner, meaning he often used expressive slides into notes and some dramatic tempo changes for effect. This will not be to everyone’s taste, but I love it. Huberman’s playing had an agitated and fiery quality about it, but his ringing tone is captivating and unmissable. From the first entrance we are given notice of Huberman’s direct and engaging style. You are unlikely to find a performance as involved and exciting from the violin perspective, but Szell and the VPO are masterful as well, anticipating every move from Huberman. One reviewer noted this performance has more in common with modern performances and I agree. It doesn’t linger and both Huberman and Szell are direct and unsentimental in their approach, but this is just fun music-making. The sound, especially from the orchestra, is not to modern standards as you might expect from 1934, there is boxiness and boominess, distortion, and some crackling. But the violin part is captured marvelously.

As mentioned above, David Oistrakh and the Beethoven concerto are a good combination. In addition to the essential recording, another Oistrakh recording stands out. His live 1954 recording with Sixten Ehrling and the Stockholm Festival Orchestra on EMI/Warner (also other labels) shares many of the same qualities as the stereo Cluytens above, and is marginally more exciting (although the sound is not nearly as good, too much boxiness and shrillness). But Oistrakh’s technique is every bit as impressive and disarming. We hear his graceful and rounded tone, his intelligent phrasing, and his willingness to let the notes unfold without pushing or pulling. Oistrakh perfectly captures the lyrical essence of this work while still bringing flashes of incredible virtuosity. There is a bit more energy from Oistrakh than on the essential version, but the Stockholm orchestra is not the equal of the ONF and the sound can be problematic. Still, well worth hearing.

Okay I promise I am almost finished with the historical recordings. Also from 1954 is a wonderful performance from Hungarian violinist Johanna Martzy together with the Orchestra della Radio della Svizzera Italiana with conductor Otmar Nussio on the Doremi label. What a beautiful tone Martzy creates! On top of that, Martzy is technically immaculate as well as forward driven and appropriately expressive. Phrasing is intense and tension is maintained throughout. The cadenzas are fiery and thrilling. Martzy’s singing tone is shown to great effect in the Larghetto, and the Rondo is jovial and sprung. This recording left me wishing there were more recordings of Martzy out there, I was spellbound by her style. She reminds me of Nathan Milstein. This recording was taken from a radio broadcast, the sound is perfectly acceptable if a bit boxy.

Speaking of Nathan Milstein, his 1955 recording with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra under William Steinberg, recorded by EMI/Warner in the Syria Mosque in Pittsburgh, is recommended. Recorded at the height of his career, Milstein is captured magnificently with his warm and ringing tone. Milstein also wrote his own cadenzas for the concerto, in my opinion one of the more successful cadenzas out there. The PSO under Steinberg is not mere window dressing either, their contribution sounds terrific. Milstein is not in the Oistrakh mold, but is rather more like Heifetz in his technical ease and somewhat unsentimental style. The directness of Milstein’s approach is its own advocate, though some will miss Oistrakh’s rounded tone. Milstein’s silvery tone is full enough, but leaner than Oistrakh (even though they shared a violin teacher). One of Milstein’s teachers was also Eugène Ysaÿe, and Milstein is more akin to Ysaÿe in technique. In any case, enjoyed on its own terms this is a wonderful performance. I should mention there is a YouTube video of Milstein performing the Beethoven concerto in 1972 with Sir Adrian Boult and the London Philharmonic Orchestra at Royal Festival Hall which many folks rave about. It is also an interesting performance, though the sound is not great.

Polish-British violinist Ida Haendel was one of the greats and had a long and productive career. Her live 1957 recording with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Karel Ančerl on Supraphon is one of my favorites. The sound is not even up to 1957 standards, and has some shrillness on the top. But the performance is amazingly alive and spirited. Haendel had an old-fashioned fast vibrato, and included some swoops and slides in her playing just as some others of her generation. But nevermind, this is playing of such distinction and sensitivity one cannot help but be moved. The Larghetto is spellbinding and the Rondo is playful and nuanced. Another reason to love this recording is Haendel’s use of Joachim’s cadenzas, which are of great interest. Since major streaming services no longer seem to carry many Supraphon recordings, I found this on YouTube.

Which brings us to another “rival” of Oistrakh, that being Ukraine born Soviet violinist Leonid Kogan, and his amazing recording from 1959 with Constantin Silvestri and the Orchestre de la Société des concerts du Conservatoire (precursor to the Orchestre de Paris), recorded by Columbia in the wonderful acoustic of the Salle Wagram in Paris. I admit it, I am a sucker for Kogan’s clear and pure tone and old school fast vibrato. Kogan creates such a sweet tone, and knows when to play with more force and when to just sing. The performance itself is fairly traditional in terms of tempos, but I find the Paris orchestra and Silvestri excellent contributors. Kogan has a leaner tone than Oistrakh (similar to Milstein), but a sweeter tone than either, and for some reason I respond to it.

Austrian violinist Wolfgang Schneiderhan “owned” the Beethoven Violin Concerto in a way few violinists have. The concertmaster for the Vienna Symphony Orchestra and then the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Schneiderhan maintained a solo career at the same time as he was in those posts. I should mention Schneiderhan joined the Nazi party in 1940, though I cannot find any sources to confirm whether he joined willingly or not. In any case, Schneiderhan’s 1962 account of the Beethoven concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra led by Eugene Jochum on the Deutsche Grammophon has been a classic since it was released. This is a traditional reading, with Schneiderhan providing a patrician reading which is very satisfying if not exactly electrifying. The playing is beautiful, and Jochum leads a BPO which acts as a perfect complement to Schneiderhan’s performance. You won’t find the warmth of Oistrakh or Perlman, or the clarity of Kogan or Kremer. But this is a lively performance which contains some lovely playing from Schneiderhan. The sound is very good for its time. The cadenzas are one of the most interesting aspects of this performance. Schneiderhan uses his own arrangement of the cadenzas Beethoven wrote for the piano version of the concerto, and it works well.

The French violinist Christian Ferras was a star in his prime, and he recorded the Beethoven concerto several times. Ferras was an artist who played the violin with a deep amount of feeling and was almost incapable of producing a boring note. When he plays, you feel the emotions in a way that few others can elicit. His most famous recording of the Beethoven concerto is from 1967 with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and Herbert von Karajan on the Deutsche Grammophon label. It is justly celebrated for Ferras’ heart-on-sleeve approach and for the heavenly Larghetto he plays. But to be honest, the entire performance is too slow for my taste. Whether that is Karajan’s influence or Ferras I don’t know (though Karajan with Anne-Sophie Mutter is similarly laborious), but I very much prefer Ferras’ 1963 collaboration with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Sir Malcolm Sargent on EMI/Warner. It is more lively and more reasonably paced, but you still get Ferras’ passionate and lyrical violin in good sound (if not quite as good as with Karajan). Other listeners like Ferras’ 1951 mono recording with Karl Böhm on Audite when he was just 18 years old, although the sound is rougher and overall it is not as recommendable as the two above.

Belgian violinist Arthur Grumiaux, one of the greatest violinists of the twentieth-century, had a truly golden tone and nearly flawless intonation. His 1974 recording with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam with Colin Davis on Universal/Decca is one of the finest examples of his artistry. This is playing of nobility and dignity, with Grumiaux playing the notes as though it is part of his very being. There is a naturalness and ease to his virtuosity, but he also carries authority and weight in his tone. His rather rapid vibrato recalls an older style, but it is absolutely charming. Davis’ accompaniment is solid and effective without any flashiness, and the warmth of the recording from the Concertgebouw still sounds superb today.

Also from 1974 comes the Polish-Mexican violinist Henryk Szeryng joined by the same Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam for another wonderful recording, this time with Bernard Haitink conducting (also on Universal/Decca). Szeryng played with a less obvious vibrato than Grumiaux, but the two had more similarities than differences. Szeryng plumbs the depths perhaps more than Grumiaux, and shows slightly more variation in expression and dynamics. His tone is simply beautiful, so much so that it feels like you could listen to it all day. This recording has a great deal of warmth in the sound, and marginally more orchestral definition than the Grumiaux version. Haitink is his reliable, if rather leisurely self, with the first movement stretching beyond 26 minutes. Somehow it doesn’t feel that long with Szeryng. Szeryng also distinguishes this recording from some others in his use of the Joachim cadenzas, providing a fresh alternative to the usual Kreisler cadenzas. In summary, a poetic and majestic account of this old warhorse.

Israeli-American violinist Itzhak Perlman has recorded the Beethoven concerto twice for EMI/Warner, the first a legendary recording from 1980 with Carlo Maria Giulini and the Philharmonia Orchestra. Many have lauded Perlman’s warm and genial tone are indeed alluring, and he seems to have an ideal personality for this work (similar in some ways to Oistrakh). In his prime Perlman produced a ravishing and singing tone, and it is on full display here. At times I find myself almost being put to sleep by Giulini though, as by this time in his career he was slowing everything down a bit much. The orchestral sound is good, though at times not well-defined. I may be in the minority on this, but I prefer Perlman’s 1989 live recording with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and Daniel Barenboim and in fact it is a version I treasure. Also on EMI/Warner, it was recorded in the Berlin Konzerthaus (rather than the Philharmonie), which lends extra warmth to the recording. Perlman’s performance is slightly more relaxed, but also more spontaneous, and I believe this is a better performance all around. Barenboim is more alert to the forward pulse needed, and orchestral lines are more sharply defined. Listen at 14’02” in the first movement, it gives me chills every time. When it comes to Perlman, I predict you would not be disappointed with either version.

In 1993, a short time after his groundbreaking Beethoven symphony cycle of the early 1990s, Nikolaus Harnoncourt recorded the Violin Concerto with the eclectic Latvian violinist Gidon Kremer joined by the Chamber Orchestra of Europe on Teldec (now Warner). For several years this was my favorite recording of this work due to Kremer’s clean and pure tone and rather unsentimental technique and Harnoncourt’s insightful scholarship, historically informed manners, and totally fresh way with Beethoven. It felt so original at the time, but of course since then their approach has been imitated by many others. I still find it highly recommendable and in excellent sound. The choice to use the cadenzas from the piano version, played on the piano, remains unconvincing for me but it is certainly different. But in other ways too this is a unique version which is well worth having as part of your collection, even if it might not be a “standard” choice.

In more recent decades recordings of the concerto have gravitated toward smaller, chamber sized orchestras and more period instrument performances, which feature less vibrato, generally quicker tempos, and sharper angles of attack. One of the finest of these is the 1997 Philips/Universal recording by Thomas Zehetmair and the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century led by Frans Brüggen. This is an exciting and lithe reading, full of vitality and spark. You must be okay with thinner textures and more transparency, and of course the quicker speeds. Zehetmair is completely convincing, and what I especially like is he never feels the need to “overplay” but keeps things balanced and relatively light. Brüggen was always one of my favorite historically informed period instrument advocates because he never took things too far in my opinion. It is true this is a more classical approach, so don’t expect Oistrakh or Perlman to show up with a thick and creamy tone. The sound is good, if a tad too resonant and boomy. But in terms of energy paired with good taste, this is heartily recommended.

If you are looking for a period performance with a marginally more meat on the bones, the 2003 recording by Russian-born British violinist Victoria Mullova with John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique on the Decca label. Mullova’s playing has at times been labeled as cool or detached, but similar to Zehetmair this is an essentially classical approach to the concerto rather than a romantic one, and so you don’t listen to this with the expectation it will be in the romantic vein. There is no schmaltz here. What Mullova brings to her terrific performances and recordings of Bach and Vivaldi, she brings to this recording as well. There is clarity, poise, a lightness of touch, and bursts of energy. Personally I like a more hybrid approach such as Kremer/Harnoncourt, but this is very good. Mullova uses less vibrato than we hear on more traditional accounts, and of course Gardiner leads a smaller orchestra. Tempos are not frenetic, but Gardiner keeps things moving. The woodwinds and brass are especially noteworthy. Mullova uses cadenzas by period specialist Ottavio Dantone. The acoustic is friendly, but not overly resonant.

I saw German violinist Christian Teztlaff perform the Beethoven concerto in 2006 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under James Levine (Teztlaff also performed the Schoenberg concerto in the same program), and I remember after leaving feeling quite impressed. Teztlaff has recorded the Beethoven concerto twice, and both of them are recommended here. The first is from 2006 (not coincidentally probably) with David Zinman and the Tonhalle Orchester Zurich, originally on the Arte Nova label which is now Sony. This performance has some similarities with the Kremer/Harnoncourt above, and while the Zurich forces use modern instruments, Zinman was keen at the time to use period-informed practices and so we hear less vibrato, sharper accents, and quicker tempos. Tetzlaff’s tone is a good fit for this approach as it tends to be lean and laser focused. Listening to this recording again, it brought back to me how much I like it. The sound is close, rich, and defined and Zinman achieves a wonderfully transparent sound from the orchestra. Tetzlaff occupies a middle ground between a classical and romantic approach, which I find appealing. Tetzlaff also recorded the concerto more recently with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin under Robin Ticciati on the Ondine label. It has many of the same great qualities as the Zinman, and if anything is more incisive and exciting. The sound engineering is immaculate too, one of the best sounding recordings I’ve heard of the concerto. The acoustic is drier than Zurich but still good enough to allow for a wide dynamic range. Ticciati and the DSO Berlin use little vibrato, but pack plenty of punch too. This is a fully mature reading by Teztlaff, leaving nothing to chance. His goal of being primarily a chamber artist shows too, with his interplay with the orchestra being notably excellent. His lean tone is very modern sounding, which is not a bad thing at all. In short, Teztlaff has made two of the best recordings of this concerto.

Another fine German violinist, Isabelle Faust, has also recorded the concerto twice. For me, her first recording from 2007 with the Prague Philharmonia under the late Czech conductor Jiří Bělohlávek on the Harmonia Mundi label is the one to have. Her second recording with Claudio Abbado and the Orchestra Mozart (also on HM) is also noteworthy but doesn’t put it all together as well as this earlier one. There is no question Faust is one of this generation’s most accomplished and celebrated violinists, and one reason is her modern, lean sound created by using less vibrato. This is not to everyone’s taste, but clearly she is very popular today, and of course she is able to adapt her style to the work at hand. Going back to hear this recording several times, I was struck by how intimate and yet powerful the sound is from the Prague orchestra, which is more of a chamber sized group. There is a nice amount of air around the sound, a pleasant resonance. Bělohlávek, more known for his Dvorak and Smetana recordings, is superb here dynamically and in terms of phrasing. This is a riveting account. Faust enters with her silvery, angelic, and slightly astringent tone, her intonation and phrasing just ideal. She uses vibrato sparingly, though still more than on her later recordings. There is excitement and adrenaline throughout, and even the Larghetto is given a lovely, light-hearted reading. The Rondo is fun and taken at just the right clip. Warmly recommended.

Georgian violinist Lisa Batiashvili recorded the Beethoven concerto in 2008 for Sony, joined by the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen and conductor Paavo Järvi. I love this recording, and it is the main reason I have remained a fan of Batiashvili to this day. The clarity of tone she produces, the subtle way she approaches phrases, and her considerable agility make this memorable for me. The Bremen group is one of the finest chamber orchestras in the world, and this was recorded during Järvi’s very successful time leading them. So you can expect modern instruments with some historically informed practice, more transparency, punchy tuttis, and some sharp accents. But don’t be lulled into thinking they can’t bring the power (listen from 19’30” to 19’50” in the first movement). It is the little things Batiashvili does which endear me so much to her playing, the way she projects her sound when needed while also employing a deft and sensitive technique, and she makes it sound spontaneous which is not easy to do with this overplayed concerto. There is no showing off, but gosh she makes it sound so easy. The sound is very good.

The Canadian violinist James Ehnes has made so many solid and unpretentious recordings in recent years, we may take his artistry for granted. But that would be a mistake. His 2017 recording of the Beethoven concerto with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and Andrew Manze (himself a gifted Baroque violinist) on the Onyx label is so good it may serve as a splendid standard recommendation of this concerto for a new listener. This is relatively big orchestra style Beethoven, but it doesn’t feel that way because the RLPO is so nimble under Manze, ever alert to the forward pulse needed. Textures are natural and transparent, tuttis are appropriately stirring, and things never become dull. Ehnes uses the Kreisler cadenzas, and if his fairly romantic approach hearkens back to Perlman, that is all to the good. The balance between soloist and orchestra is expertly managed by Manze, and he proves himself a wonderful collaborator. The sound is open and realistic. A very satisfying version.

German violinist Frank Peter Zimmermann has also recorded the Beethoven concerto several a few times in addition to a few other live recordings. The best of these is his most recent one with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra with Daniel Harding on the BPO’s own label, recorded in 2019. This is a refined performance, impeccably played by Zimmermann in a clear acoustic. The orchestral contribution is powerful, and yet well controlled. This is the version of the BPO which shows up as the finest orchestra in the world, and I like Harding at the helm better than their primary conductor these days. Zimmermann knows this concerto inside and out, and this is a mature interpretation where he maintains a wonderful singing line throughout, emphasizing a lyrical sense in even the smallest phrases. The outer movements are my favorite parts of this recording, where Zimmermann and Harding seem to let loose more. The Larghetto is not heart on the sleeve but instead rather unsentimental. This is a modern account in terms of pacing, phrasing, and sensibility and it eschews an overly romantic approach. It is thrilling in its own way, even if it doesn’t pull any heart strings. The sound is excellent.

Israeli violinist Vadim Gluzman seems to fly under the radar quite a bit, but I remember how immediately impressed I was by his Tchaikovsky concerto recording. His Beethoven recording, made in 2019 by BIS with James Gaffigan and the Lucerne Sinfonieorchester, is another winner and includes cadenzas by Alfred Schnittke, which I might add are very interesting. I like what I’ve heard from James Gaffigan as well, although I find the orchestra here to be placed too far away in the sound picture. It may just be my low-tech equipment, but it seems to be a consistent issue throughout. Gluzman’s violin is captured very well on the other hand, and his playing has a self-assurance which I enjoy. His beautifully rounded tone and natural style are nothing groundbreaking in this work, but what he does is balance the lyrical and dramatic elements well. The Schnittke concerto it is paired with is even more impressive, and certainly a unique pairing.

Award winning American violinist Gil Shaham had never recorded the Beethoven concerto until his 2019 outing with the chamber group The Knights led by Eric Jacobsen on Shaham’s own Canary label. This is an invigorating reading that brings a freshness and newly minted feel to the concerto. The Knights are a Brooklyn, NY based group formed by a group of musicians from The Julliard School. Shaham and The Knights seem to be completely in sync where they can ideally anticipate each other. Like many modern recordings of this concerto, the classical structure and musicality is emphasized more than the romantic. Yet, this is not a period performance and so the sonority is fuller and Shaham does employ a fair amount of vibrato. Here the concerto sounds like a chamber concerto, with the interplay between soloist and orchestra closely tied together in a coherent way. Textures are not thick, meaning we hear individual instruments quite well. Tempos are flexible, certainly not too fast, but also the tension never drags. The sound engineering is top notch.

I have admired Leonidas Kavakos for some time now, and I especially enjoyed his complete set of the Mozart concertos. Kavakos plays the violin and leads the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra on this 2019 recording on Sony. His Beethoven concerto recording is a throwback to the days of slower tempos, thicker orchestral textures, and a more romantic approach. Perhaps in the midst of the many modern recordings of this concerto which tend to sound the same after a while, Kavakos has struck upon something important: the essentially lyrical aspect of the work. His vision of the concerto is decidedly slow, and this is purposeful from beginning to end. Whatever is lost in terms of impetus and energy is more than compensated by the expressive lyricism along with the beauty of Kavakos’ tone and the way the BRSO follows his lead. After listening to this one several times I have become convinced this is a wonderful new take on the concerto, and Kavakos justifies the slower pace with characterful playing and the well-done cadenas. Recommended.

With a work as familiar and as often played and recorded as the Beethoven concerto, it is often difficult to bring anything new or different to a performance that hasn’t already been done. However, Nemanja Radulović and the chamber group Double Sens are quite successful in making the concerto sound fresh and interesting on their 2022 recording on Warner. Like many recent recordings they favor less vibrato and leaner string textures, but tempos are well within the average range compared to other recordings. Where Radulović stands out is in his imaginative and effective phrasing, and his conductor-less chamber orchestra follows suit. The energy, clean articulation, and forward thrust are palpable, and the overall impact is invigorating. Beyond a few obvious places where the performance is different (like the interesting phrase inserted at 2’43” in the Rondo, and at how the orchestra enters immediately at about 4’40” where there is usually a pause), what I really love about this recording is the freedom of expression Radulović uses himself, and encourages from Double Sens. Occasionally I found myself longing for a richer sound and more rubato like you might hear from Itzhak Perlman or David Oistrakh, but what this performance lacks in fullness of sound it more than makes up for in its wide range of emotional expression. The central Larghetto is particularly sensuous and refined, and I am impressed by how Radulović can vary the dynamics and indeed his own volume and tone in ways that are moving. Very enjoyable.

Honorable Mention

I can say in all honesty many of the recordings below are also quite distinguished, and some listeners may find them to be highly recommended. At some point there are just too many recordings to hear! But there are some excellent ones in the mix.

Isolde Menges / Royal Albert Hall Orchestra / Sir Landon Ronald (Biddulph 1023)

Adolf Busch / New York Philharmonic / Fritz Busch (Biddulph 1942)

Erich Röhn / Berlin Philharmonic / Wilhelm Furtwängler (DG 1944)

Jascha Heifetz / New York Philharmonic / Arthur Rodzinski (Doremi 1945)

Gerhard Taschner / Berlin Philharmonic / Georg Solti (Archipel 1947)

Yehudi Menuhin / Lucerne Festival Orchestra / Wilhelm Furtwängler (Warner 1948)

Ginette Neveu / SWR Orchestra Baden-Baden / Hans Rosbaud (SWR 1949)

Zino Francescatti / The Philadelphia Orchestra / Eugene Ormandy (Sony 1950)

David Oistrakh / Moscow Symphony Orchestra / Alexander Gauk (Andromeda 1950)

Jascha Heifetz / Hollywood Bowl Symphony / Serge Koussevitzky (Doremi 1950)

Christian Ferras / Berlin Philharmonic / Karl Böhm (Audite 1951)

Alfredo Campoli / London Symphony Orchestra / Josef Krips (Decca 1952)

Ruggiero Ricci / London Philharmonic Orchestra / Adrian Boult (Decca 1952)

Camilla Wicks / New York Philharmonic / Bruno Walter (Profil 1953)

Wolfgang Schneiderhan / Berlin Philharmonic / Paul van Kempen (DG 1953)

Yehudi Menuhin / Philharmonia Orchestra / Wilhelm Furtwängler (Warner 1953)

Christian Ferras / SWR / Hans Müller-Kray (SWR 1954)

Bronislav Gimpel / Bamberg Symphony / Heinrich Hollreiser (Biddulph 1955)

Mischa Elman / London Philharmonic Orchestra / Georg Solti (Decca 1955)

Arthur Grumiaux / Concertgebouw Amsterdam / Eduard van Beinum (Decca 1957)

Isaac Stern / New York Philharmonic / Leonard Bernstein (Sony 1959)

Henryk Szeryng / London Symphony Orchestra / Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt (Decca 1965)

Isaac Stern / New York Philharmonic / Daniel Barenboim (Sony 1976)

Frank Peter Zimmermann / English Chamber Orchestra / Jeffrey Tate (Warner 1988)

Nigel Kennedy / North German Radio Orchestra / Klaus Tennstedt (Warner 1992)

Kyung Wha Chung / Concertgebouw Amsterdam / Klaus Tennstedt (Warner 1992)

Pinchas Zukerman / Los Angeles PO / Zubin Mehta (RCA/Sony 1992)

Hilary Hahn / Baltimore Symphony Orchestra / David Zinman (Sony 1998)

Aaron Rosand / Monte Carlo / Derrick Inouye (Vox 1998)

Frank Peter Zimmermann / Staatskapelle Dresden / Bernard Haitink (Profil 2002)

Joshua Bell / Salzburg Camerata / Roger Norrington (Sony 2002)

Nikolaj Znaider / Israel Philharmonic / Zubin Mehta (Sony 2005)

Vadim Repin / Vienna Philharmonic / Riccardo Muti (DG 2007)

Rachel Barton Pine / Royal Philharmonic Orchestra / Jose Serebrier (Cedille 2007)

Arabella Steinbacher / West German Radio Orchestra / Andris Nelsons (Orfeo 2008)

Patricia Kopatchinskaja / Champs-Elysees / Philippe Herreweghe (Naive 2009)

Janine Jansen / Bremen Kammerphilharmonie / Paavo Järvi (Decca 2009)

David Grimal / Les Dissonances (LD 2010)

Isabelle Faust / Orchestra Mozart / Claudio Abbado (HM 2012)

Augustin Dumay / Sinfonia Varsovia (Onyx 2015)

Sayaka Shoji / St. Petersburg Philharmonic / Yuri Temirkanov (DG 2018)

Vilde Frang / Bremen Kammerphilharmonie / Pekka Kuusisto (Warner 2021)

Veronika Eberle / London Symphony Orchestra / Sir Simon Rattle (LSO 2022)

María Dueñas / Vienna Symphony Orchestra / Manfred Honeck (DG 2022)

Whew! That was long. I apologize. I will try to keep the length down in the future, but the next work is Johannes Brahms’ Symphony no. 1 so that one will also be epic.

As always I appreciate your feedback and messages, and I do my best to keep up with them. Thank you again for your readership, and happy listening!

___________________

Notes:

Lemco, Gary. Johanna Martzy, Vol. 2 = BEETHOVEN: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61; MOZART: Violin Sonata in B-flat Major, K. 454 – Johanna Martzy, violin/Jean Antonietti, piano/Radio Svizzera Italiana Orchestra/Otmar Nussio. Online review at https://www.audaud.com/johanna-martzy-vol-2-beethoven-violin-concerto-in-d-major-op-61-mozart-violin-sonata-in-b-flat-major-k-454-johanna-martzy-violinjean-antonietti-pianoradio-svizzera-italiana-orchestra/page/3/?et_blog.

Mandel, Marc. Beethoven Violin Concerto. Online at https://www.bso.org/works/violin-concerto-2.

Mandel, Marc. Beethoven Violin Concerto. Boston Symphony Orchestra program notes. November 2006. Pp. 41-47.

https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/40589.Ludwig_van_Beethoven

Just fabulous! Every time you put out a new piece you give me a revelation. For example Christian Ferras, who Sibelius is one of my favorites, I never listened to his Beethoven, but naturally would have checked out the Karajan recording because its what Tidel has 20 versions off. But this one with Sargent is a clear gem!

I don’t know if you have an idea of what you will do after this monolith of a project, but I would love a best and worst of great artist. Like Karajan or Ferras what they did that was a revelation and what seems not quite strong. Thanks for all your time and thoughtfulness! The musical journalism I admire the most.

John, I really compliment you for entering an essential Version of such an immense masterpice with so many wonderful available versions from every era! And more, I Absolutely agree! What an immense, powerfull and magic interpretation of Oistrach this is. And I also agree with what you say later about Gluzman version. I also discov ered him casually listening to his Tchaikovsky and was love at the first hearing.