Building a Collection #60

Violin Concerto in D minor

By Jean Sibelius

________________

Welcome back to our regular readers, and a special warm welcome to new readers and subscribers! The name of this column is Building a Classical Music Collection, and we have made it to #60 in the Building a Collection series on our way to covering the top 250 classical works of all-time. At #60 is one of the greatest violin concertos ever composed, Jean Sibelius’ Violin Concerto in D minor. I hope you will continue reading to learn more about Sibelius and this masterful concerto.

Jean Sibelius

Jean Sibelius (b.1865 – d.1957) was a Finnish composer of the late Romantic and early Modern periods of classical music. Although he was born into a Swedish speaking family (Finland was ruled by Sweden for centuries), Sibelius eventually learned to speak Finnish and later became immersed in Finnish culture. He is regarded as the greatest Finnish composer in history, and his music is especially noted for its nationalistic themes and for helping Finland develop a national identity during a time when the country was fighting for independence from Russia. Sibelius is also credited with the further development of the symphony and the tone poem as musical forms.

As a young man entering college, Sibelius was drawn more and more to music. While he began as a violinist, he soon came to realize composition was his true calling. In 1889, he traveled to Berlin to study composition, and it was there he was exposed to the music of Richard Strauss which was very influential to him. Eventually, he made his way back to Finland to teach music and in 1893 his first substantial work Kullervo was premiered to significant acclaim. Kullervo is a symphonic poem for soloists, male chorus and orchestra, and is based on the Finnish folk epic Kalevala. It was so successful that Sibelius was soon dubbed the leading composer in Finland. In 1897 the Finnish Senate decided to pay Sibelius a salary for a time, which was eventually extended to a lifetime pension. Today there is a wonderful museum dedicated to the composer in the heart of Helsinki which I was fortunate enough to visit several years ago.

Sibelius’ Symphony no. 1 in 1899 was relatively successful but was then followed in 1900 by the enormously successful and enduring work Finlandia. Finlandia is a tone poem of nationalistic importance, at least in part due to the political climate at the time when it was created. Because Finland was under Russian censorship at the time, there was the desire to break free from Russia’s czarist grip. As part of the overall movement toward a free press and freedom of expression, Sibelius composed music for a fund-raising event rallying support for a free press. It was titled Music for Press Ceremony, but the score ends with “Finland Awakens”, which would eventually be called Finlandia. Since then, Finlandia has virtually become Finland’s national anthem.

Sibelius loved nature, and his music evokes stark landscapes, cold winter scenes, and an almost other-worldly atmosphere. Sibelius developed his own unique sound that can be heard especially in works such as En saga, The Swan of Tuonela, Valse Triste, Symphonies 1, 2, 5, and 7, and his Violin Concerto. Sibelius met the composer Gustav Mahler in 1907, and they discovered they had some things in common. Generally speaking, as both of them matured as artists and developed their styles during the early 20th century, critics were brutal in their assessment of anything that strayed from the traditional path. Since both men were pioneers in their own ways, it took courage for both of them to remain true to their own artistry. It was Sibelius’ goal to write music that was distinctively “Finnish”, and I think we can agree he was able to achieve that goal.

Sibelius achieved great fame in his lifetime, but also went through difficult periods. He was a heavy drinker and smoker for much of his life, and this led to marriage problems. Eventually he gave up those vices and lived a relatively peaceful life in his later years. During the last 30 years of his life, Sibelius composed very little new music but continued to make revisions of his earlier works. He made frequent trips to England, where his music was widely embraced by audiences.

Violin Concerto

Sibelius’ Violin Concerto is the largest concerto type work he composed, and even though it was slow to catch on with audiences and critics, it began to gain recognition after the famous violinist Jascha Heifetz recorded it in the 1930s, and today it takes its rightful place as one of the most loved violin concertos ever written. It is certainly one of a handful of the most popular works by Sibelius, and virtually every virtuoso violinist that comes along must record their version of it at some point.

Sibelius completed the concerto in 1903, intending for his friend Willy Burmester to be the soloist for the premiere in Helsinki with Sibelius conducting. But due to scheduling and travel issues with Burmester, Sibelius decided to use the Hungarian music professor Victor Nováček on violin for the premiere on February 8, 1904. Sibelius was working on the piece right up until the premiere, and the lack of rehearsal time plus the difficulty of the score for Nováček, contributed to the disastrous performance and initial reception. Sibelius was so embarrassed he withdrew the work from publication and was determined to revise the work.

The revised version was premiered in 1905 in Berlin with Richard Strauss conducting and soloist Karel Halíř stepping in. The work was more warmly received, and it is usually this revised 1905 version we hear today. Sibelius reworked some of the solo passages to make them more playable (even though they remain tremendously difficult), and some other parts were cut. The concerto movements are as follows, with the description of each movement provided by Michael Steinberg:

Allegro Moderato

Sibelius gives unprecedented importance to his first-movement cadenza (when the violinist plays a virtuosic section alone, without accompaniment). What leads up to that big cadenza is a sequence of ideas that begins with the sensitive, dreamy melody that introduces the voice of the soloist. This leads to what we might call a mini-cadenza, starting with a flurry of notes marked veloce (rapid). From this there emerges a declamatory statement upon which Sibelius’s mark is ineluctable—an impassioned, super-violinistic recitation. Then the orchestra joins in music that slowly subsides from furious march music to wistful pastoral to darkness. It is out of this darkness that the cadenza erupts, an occasion for sovereign virtuosity, brilliantly, fancifully, and economically composed.

Sibelius set store by having composed a soloistic concerto rather than a symphonic one. It seems an odd point for him to be so stubborn about it for so long. He opposes rather than meshes solo and orchestra. The first movement, with its daring sequence of disparate ideas, its quest for the unity behind them, its bold substitute for convention, its wedding of violinistic brilliance to compositional purposes, is one that bears the unmistakable stamp of the symphonist—perhaps the greatest symphonist after Brahms.

Adagio di molto

The Adagio is one of the most moving pages Sibelius ever achieved. Clarinets and oboes in pairs suggest a rather tentative idea; this is a gentle beginning, leading to the entry of the solo violin with a melody of vast breadth. It speaks in tones we know well and that touch us deeply. Sibelius never found, perhaps never sought, such a melody again: This, too, is farewell. Very lovely, later in the movement, is the sonorous fantasy that accompanies the melody (now in clarinet and bassoon) with scales, all pianissimo (very quietly), moving up in the violin, and with a delicate rain of slowly descending notes in flutes and soft strings.

Allegro, ma non tanto

Evidently a polonaise for polar bears,” said British writer and musicologist Donald Francis Tovey of the finale—a remark it seems no writer can resist quoting. The charmingly aggressive main theme was an old one, going back to a string quartet from 1890. The enlivening accompaniment in the timpani against the figure in the strings is one of the fruits of revision. As the movement goes on, the rhythm becomes more and more giddily inventive, especially in the matter of the recklessly across-the-beat bravura embellishment the soloist fires across the themes. It builds to a drama to end in utmost and syncopated brilliance.

The cadenza in the first movement is unusual because it is placed in the center of the movement. A cadenza is a portion of a concerto in which the orchestra stops playing, leaving the soloist to play alone in free time, and can be written or improvised depending on what the composer specifies. Most often cadenzas are placed closer to the end of the movement, but Sibelius put it in the middle, and for this concerto it is an extended written cadenza.

The opening of the concerto is one of the most appealing and intriguing beginnings to any concerto. Even though the shimmering strings are reminiscent of a cold, Nordic landscape, Sibelius actually wrote the first sketches for this in 1901 during a trip to Italy. The emergence of the violin within the shimmering is magical and other-wordly. What is most striking to me is how deeply felt this concerto is, and just how much emotion it elicits in the listener. The stereotype of Sibelius as a “cool” composer is turned completely on its head. The work burns with an inner light. One theory is that Sibelius poured into the piece his own frustrations and pain at failing to become a great violinist, as he had shown some real talent as a young man. In 1891, he auditioned for the Vienna Philharmonic but was denied acceptance. There is no doubt Sibelius instilled a great deal of knowledge and sentiment into the concerto, as well as some devilish virtuosic demands.

The Sibelius concerto stands out for its unique and modern flavor as well. The first movement Allegro moderato contains some disparate ideas, some not working back towards the main theme but rather standing as their own statements. But when the main theme reaches its climax, once in the first part of the movement and again in the last part, we are treated to some of the most sublime violin phrases ever written.

Similarly, the Adagio is one of the most moving creations in any concerto. But it is presented in a way that, again, there are parts that don’t seem to fit the whole and that speaks to a melancholy and brokenness that cuts to the reality of our humanity. Yet the tenderness and expressivity pulls directly at our heart, and the handful of times the violin achieves a true pianissimo are each precious and deeply felt. It is haunting in the best possible way.

The finale is Allegro ma non tanto and is rhythmically infectious and almost has a gypsy feel to it. This movement is inventive in its use of off-beat syncopations and unexpected twists and turns. It is so much fun, and while it may feel like a departure from the previous two movements, it completes the concerto in a most satisfying way. We still hear the chromatic flashes which make it sound so modern, and we continue to hear Sibelius’ own voice as a composer. In this, he manages to merge melody and rhythm in a style that is utterly unique and beguiling.

Recommended Recordings

Before we get into the details on recordings, I want to say there are simply too many outstanding recordings of this concerto to pull out which ones are “essential”. Recordings have also broadened over the years, with performers slowing things down to draw out every drop of emotion, a strategy that at times can be detrimental to the required momentum and tension. The orchestra accompaniment is important too, though perhaps not as much as other concertos. Even so, a pedestrian or uninvolved orchestra can drag down the entire recording.

You might also notice that the amount of vibrato employed by the soloist has changed over the years as well. The “old school” soloists such as Heifetz, Oistrakh, Haendel, Stern, and others used more vibrato, and it was a faster vibrato. More modern soloists such as Jansen, Teztlaff, Lin, Skride, and others still use vibrato but in general employ it more sparingly. Personally, I don’t have a preference, but some listeners may prefer one or the other.

One more thing to mention, and that in his orchestration for the concerto Sibelius is careful not to drown out the violin with the orchestra. He does this by keeping the orchestral notes lower on the scale than the violin, which gives the concerto a darker, brooding flavor. He controls the dynamics as well but is more interested in painting the overall hues and backdrop rather than spotlighting specific instruments. This allows the violin to truly shine and to stand out from the orchestral voices. Successful recordings make the most of this, with conductors that know when to let the reins loose on the orchestra and when to pull back, so the focus is on the soloist.

The oldest full recording of the Sibelius Violin Concerto remains one of the best, and for some the definitive recording of the concerto. I am referring to the 1935 recording by the legendary Jewish Russian American violinist Jascha Heifetz accompanied by the London Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Sir Thomas Beecham recorded by EMI/Warner at Abbey Road Studios in London (now available on Naxos as well). The sound has some limitations, but still sounds relatively good in its current remastering, although there is some expected boxiness. This is a masterful performance as Heifetz is in brilliant form, bringing incisiveness and dazzling precision. It is quicker than most modern versions as was the style at the time, but it still carries a great deal of charm, sensitivity, and emotion. Heifetz’s later recording from 1959 in Chicago with Walter Hendl is also good and is in better sound but is played super-fast and for me it loses something of the character of the work in favor of virtuosity and flash. Beecham’s accompaniment in 1935 is also sensitive and fully involved, and the LPO go along for the ride perfectly with Heifetz. As I mentioned, for some this is still the landmark recording, and I would not argue with that assessment.

The 1953 Supraphon recording by Soviet violinist Julian Sitkovetsky (father of violinist Dmitri Sitkovetsky) and the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Nicolai Anosov (father of Soviet conductor Gennadi Rozhdestvensky) remains one of the most interesting and compelling of the historic recordings of this concerto. I located it on YouTube, as it doesn’t appear to be available on streaming services. Sitkovetsky was a brilliant young violinist, and some say he would have eclipsed Oistrakh and Kogan had he lived. Unfortunately, Sitkovetsky died from lung cancer in 1958 at the age of 32. This performance captures the violin solo well, although the orchestra is at a far distance and thus not recorded well. However, Sitkovetsky’s performance is completely masterful. You will notice his very fast vibrato which was in style at the time, and the performance as a whole is quicker than we hear today (similar to Heifetz). Sitkovetsky creates a deep and rich middle register on the violin and employs some “swoops” up to the note which again are redolent of the time period. This is a colorful and fervent reading, and very enjoyable to hear although for sonic reasons it will not be a top recommendation.

Jumping ahead to 1959 we encounter a recording full of personality and passion played by the Jewish Russian violinist Tossy Spivakovsky along with the London Symphony Orchestra led by the Finnish conductor Tauno Hannikainen on the Everest record label. First, let me say the sound is remarkably full, clear, and balanced as any recording out there, which is saying a lot for 1959. Spivakovsky was featured in a book on his own style of bowing the violin titled The Spivakovsky Way of Bowing, his goal being to draw the fullest and richest sound from the instrument. He was also a scholar, going back to the original scores to find the composers’ notations in order to reproduce a sound as close to the composers’ intentions as possible. Spivakovsky was also known for his extroverted playing style, which showed his extreme virtuosity but also his personality and temperament. In the case of this recording, Spivakovsky plays with abandon and adds some embellishments and slides, and even misses some notes (especially in the final movement coda). But this is a one-of-a-kind performance, played for all its worth with a genuine feel for the idiom while also bringing all the bravado and drama one can imagine. Spivakovsky’s tendency to draw attention to himself and his pyrotechnics won’t appeal to everyone, but I love it.

The French violinist Christian Ferras was an ultimately tragic figure, suffering from depression his whole adult life and taking his own life in 1982 at the age of 49. It is an open question as to whether his depression actually enhanced his artistry in some ways, although that is undoubtedly too high a price to pay for art. His 1964 recording of the Sibelius concerto with Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra on Deutsche Grammophon is one of the most sublime and consistently outstanding versions available. Recorded in the Jesus-Christus-Kirche in Berlin, it has warmth and power. Ferras balances the technical challenges and the expressive requirements perfectly, and Karajan is content here to serve a secondary role (which he and the BPO do marvelously). But Ferras outdid himself the following year with a live performance on the Doremi label, accompanied by the Orchestre national de l'ORTF (now known as the Orchestre National de France) conducted by a young Zubin Mehta. Ferras’ performance on this live recording is totally incandescent and unforgettable. He plays with more spirit, incisiveness, and energy and I was immediately drawn in. The sound is not nearly as good as the studio account with Karajan, but you will want to hear Ferras on the live version. Both recordings are impressive and recommended, and together they paint a more complete portrait of Ferras at the height of his career.

Legendary Ukrainian-born Soviet violinist David Oistrakh was one of the greatest violinists of the twentieth century. He recorded the Sibelius concerto at least three times, and performed it countless more times. All three of his recordings are noteworthy: the first from 1954 with the Stockholm Festival Orchestra and conductor Sixten Ehrling on EMI/Warner is a great example of Oistrakh’s artistry, although the recording is hampered by the orchestra’s placement too far in the distance and Ehrling’s somewhat matter-of-fact conducting. Oistrakh’s second recording was with Eugene Ormandy and The Philadelphia Orchestra from 1960 on Columbia/Sony. The sound is better and Ormandy and the Philadelphians are captured in good form, but Oistrakh’s performance is not as inspired as in Stokholm. Finally Oistrakh recorded the concerto again in 1965 with Soviet conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensky and the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra for the Melodiya label (the version I heard is on the Praga label). This last recording brings together both Oistrakh’s finest performance of the concerto along with a more than adequate accompaniment from Rozhdestvensky and company (in fact Rozhdestvensky was one of the most underrated conductors of his time). The sound is a bit rough around the edges, but perfectly acceptable stereo, and most importantly captures Oistrakh rather closely. This is a performance of stature and maturity, but also of urgency and electricity. Oistrakh takes a more assertive approach than some, but this is an equally valid style, and he maintains the legato phrasing when more tenderness is needed. For me this is one of Oistrakh’s finest recordings.

Ukrainian-born American violinist Isaac Stern recorded the Sibelius concerto at least three times as well, but the finest of his recordings is from 1969 with The Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy, recorded for Columbia/Sony. Stern’s view of the concerto had matured from his 1951 and 1962 readings, and this is a reading which checks all the boxes. Stern is focused, intense, and pointed in his lines and accents, and more rhythmically alert than previously, and his vision is essentially extroverted. Tempos are on the quick side, which works well with Stern’s outgoing nature. Ormandy was one of the finest Sibelius conductors of the century, and the Philadelphians are captured in all their glory. Just listen to the runup to the coda in the first movement as both soloist and orchestra rev things up…wow. That’s not to say there aren’t moments of reflection and tenderness, but this is not a reading that wallows in sentiment. It has a propulsive quality to it that I find appealing. Stern is masterful and assured, and this recording shows why he deserved the accolades.

The Polish British Canadian violinist Ida Haendel had a long and famous career, and the Sibelius concerto in particular became a calling card of sorts for her. Indeed, in 1949 the composer himself told her after a performance ‘I congratulate you upon the great success. But above all I congratulate myself, that my Concerto has found an interpreter of your rare standard.’ Haendel herself was quoted as saying of the Concerto, ‘not a work for the mediocre…There’s nowhere to hide if you play every note, and every note is very valuable’. Nicknamed “The Grand Dame of the Violin”, Haendel has four commercial recordings still on streaming services, though there are likely other recordings out there, including on YouTube. I recommend two of her recordings of the Sibelius Concerto, the first being recorded live in 1959 with the Czech conductor Karel Ančerl and the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra on the Supraphon label. Since streaming services have largely stopped streaming Supraphon recordings, I found the audio on YouTube in good sound. This is a towering performance with Haendel fully immersed in the idiom, the demands of the concerto holding no danger for her. It is intelligently crafted and impressive with excellent contributions from Ančerl and his Czech forces. I would not say it is the most deeply felt performance, but at that time this wasn’t unusual. Haendel’s 1976 recording with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra under master Sibelius conductor Paavo Berglund on EMI/Warner is warmer, broader, and more heartfelt. While I don’t think the orchestra accompaniment is quite as strong as the earlier recording, Haendel brings a rare tenderness and depth of expression that complements her earlier effort appropriately. Both approaches are appreciated and give us insight into this timeless work.

Israeli-American violinist Itzhak Perlman has recorded the Sibelius concerto twice, the first time in 1966 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Erich Leinsdorf on RCA, and the second time in 1979 with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra and conductor André Previn for EMI/Warner. It is the latter recording which is recommended, although the earlier version is worth hearing as well. By 1979, Perlman’s view of the Sibelius concerto had matured and developed into an interpretation of insight and power. With Previn, Perlman is slower but the gain in terms of lyricism and mood is definitely worth it. His tone is richer and more nuanced as well, and Previn is a much more sympathetic Sibelius conductor than Leinsdorf. Perlman’s persuasive way with the romantic score comes through well, and the violin part is brightly lit by the close recording. There is a confidence and self-assuredness that leads to a powerful and vital reading, and while the earlier recording shows flashes of brilliance, this later one is captivating from beginning to end. The Pittsburgh orchestra sounds great, and Previn is a terrific accompanist. The recorded sound is excellent, if a bit bright on the top end.

American violinist Dylana Jenson was a child prodigy and began playing the violin at the age of two. She studied with famed violinist Nathan Milstein, and appeared on the Jack Benny TV show at the age of nine. By age 13 she had appeared with many of the leading U.S. orchestras. Jenson made her Carnegie Hall debut in 1980 playing the Sibelius Concerto with The Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy. While Jenson started a family and turned more to teaching rather than performing (although she still performs occasionally), we are fortunate enough to have her recording of the Sibelius Concerto from 1981 with the same Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy on the RCA/Sony label. It is included as part of the Eugene Ormandy Conducts Sibelius boxed set. When it was released the album was heavily promoted and celebrated in popular culture due to Jenson’s exposure at a young age, and to some listeners this cheapened the experience, even though it won a Grammy Award in 1982. Nevertheless, this is an outstanding account played with energy, understanding, and power. Jenson plays with a lot of heart, and she maintains the tension and drama throughout. Her articulation is particularly precise and enjoyable. Ormandy was always a great Sibelius conductor, and this is a fine example. The album was one of RCA’s first in digital sound, and honestly it sounds terrific.

Taiwanese-American violinist Cho-Liang Lin recorded the concerto with The Philharmonia under Finnish conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen for Sony in 1988. I have owned this CD for many years, and it is still a treasured performance. The teamwork between soloist and orchestra is noticeably acute, with Lin bringing a wonderful expressivity and Salonen encouraging extreme precision and rhythmic alertness. Lin has a wonderful tone as well and is able to project his sound at will and even float some lovely, tender notes. The overall impression is of a tight and disciplined performance with a fair amount of individual style. The sound is excellent, and if I had to choose one version to recommend for a standard library choice, this would be it. This recording is also paired with what I believe is the finest version of Carl Nielsen’s Violin Concerto available.

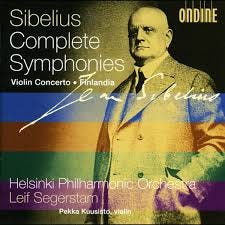

One of my terrific readers pointed out to me a splendid recording I had inadvertently omitted from my recommendations even though I had given it the highest ranking in my notes. The recording is by Finnish violinist Pekka Kuusisto joined by the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by the late Finnish conductor Leif Segerstam, recorded in 1996 for the Ondine label. As I write this on October 10, 2024, I just discovered that Segerstam passed away only yesterday at the age of 80. Kuusisto’s reading is the opposite of someone Spivakovsky, eschewing too much sentiment or overstatement. He doesn’t draw attention to his playing, but rather delivers the score in a faithful manner, remaining attentive to all the markings and dynamics. Kuusisto’s cooler approach works extremely well with this concerto, and it even adds to the haunting quality of the first and second movements. He also highlights the lyrical aspects of the score better than most, and he is really able to make the violin sing when needed but still retains the acidic quality of tone needed for Sibelius. I also admire the way he never forces anything in terms of tempo, and lets the music speak for itself. For Segerstam’s part, I love how he conducts Sibelius and his complete Ondine boxed set of the Sibelius symphonies this is paired with are also highly recommended. Segerstam makes the most of the orchestra accompaniment in building the drama, and the sound he draws from the Helsinki Philharmonic is red-blooded, warm, and detailed. The sound quality is excellent.

When I posted this entry a few days ago I had included the Sibelius Concerto by Lisa Batiashvili and the Staatskapelle Berlin under Daniel Barenboim, a recording from 2015 on the Deutsche Grammophon label. One of my subscribers wrote to me about Batiashvili’s first recording of the concerto made in 2007 with the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Finnish conductor Sakari Oramo on the Sony label, saying that this earlier recording was even better than the later one. After going back and listening to the two recordings again several times, I definitely agree. While the Barenboim recording is good, the earlier one with Oramo is preferable. Batiashvili’s sound is more focused and incisive while still retaining the essentially dreamy and ethereal qualities of her playing. Oramo and his Finnish orchestra don’t have the darker, upholstered sound of the Berlin orchestra, but they are more exciting and keep the rhythmic pulse going much better. Oramo’s pacing is marginally faster in the first two movements, which I feel is all the better for the music. The overall sound is cleaner and more present too. This replaces my earlier recommendation, and I have moved the Barenboim recording down a notch to Honorable Mention.

Another edit from my original post is the addition of the excellent live recording of the Sibelius Concerto by Taiwanese-Australian violinist Ray Chen with the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra (Sweden) under conductor Kent Nagano, recorded on March 26th, 2015, and available for viewing on YouTube or on the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra’s own site. Chen is masterful, capturing the right mood immediately and maintaining a lyrical and emotional approach throughout. He is an impressive talent, perfectly balancing expressivity, sentiment, and technical ability. The Gothenburg band is also one of the finest Sibelius orchestras in the world in my opinion, and Nagano is a sensitive and insightful partner. I listened to this with just the audio, and the sound is every bit as good as other modern recordings.

My last recommended entry is a brand new 2024 entry played by the Dutch superstar violinist Janine Jansen accompanied by the Oslo Philharmonic led by their new young Finnish director Klaus Mäkelä, released on the Decca label. The opening bars with the orchestra shimmering are eerily and magically executed, with Jansen entering seamlessly. Her statements on the violin grow in intensity as the volume increases, with the orchestra seeming to follow her at every step. Jansen is assertive, but never pushes and pulls too hard. Listen to the Adagio for some of the most breathtaking pianissimo moments, for example from 2’50” and again at 6’15”, then once again at 7’25”. Impressive stuff. Jansen plays passionately too, this is certainly a warm and engaging account. There is a halo of warmth around the orchestral sound, and yet details are not obscured. This goes for Jansen’s tone as well, she produces a warm and full tone, and there is no screeching. To Mäkelä’s credit, he is at least somewhat unobtrusive on this recording, which allows the listener to focus on Jansen’s terrific musicality. I must also add I enjoy the dark and rich tones from the Oslo strings and woodwinds. But for me, it is Jansen raises this recording to the top tier of Sibelius concerto recordings.

Honorable Mention

The truth is there are many more excellent recordings of this concerto, and as it does so often, it comes down to taste. In many cases there are only minute details separating the recordings listed above from the list below, and you may very well find your favorite among them.

Ginette Neveu / Philharmonia Orchestra / Walter Susskind (Warner 1945)

Isaac Stern / Royal Philharmonic Orchestra / Sir Thomas Beecham (Sony 1951)

Camilla Wicks / Stockholm Radio Symphony Orchestra / Sixten Ehrling (Biddulph 1952)

Jascha Heifetz / Chicago Symphony Orchestra / Walter Hendl (RCA/Sony 1959)

David Oistrakh / The Philadelphia Orchestra / Eugene Ormandy (Sony 1960)

Zino Francescatti / New York Philharmonic / Leonard Bernstein (Sony 1963)

Itzhak Perlman / Boston Symphony Orchestra / Erich Leinsdorf (RCA/Sony 1966)

Kyung Wha Chung / London Symphony Orchestra / Andre Previn (Decca 1970)

Masuko Ushioda / Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra / Seiji Ozawa (EMI/Warner 1972)

Pinchas Zukerman / London Philharmonic Orchestra / Daniel Barenboim (DG 1975)

Ida Haendel / Israel Philharmonic / Zubin Mehta (Decca 1982)

Gidon Kremer / Philharmonia Orchestra / Riccardo Muti (Warner 1983)

Victoria Mullova / Boston Symphony Orchestra / Seiji Ozawa (Decca 1986)

Shlomo Mintz / Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / James Levine (DG 1987)

Silvia Marcovici / Gothenburg Symphony / Neeme Järvi (BIS 1987)

Nigel Kennedy / City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Simon Rattle (Warner 1988)

Leonidas Kavakos / Lahti Symphony Orchestra / Osmo Vänskä (BIS 1991)

Joseph Swensen / Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra / Jukka-Pekka Saraste (RCA 1992)

Frank Peter Zimmermann / Philharmonia Orchestra / Mariss Jansons (Warner 1992)

Gil Shaham / Philharmonia Orchestra / Giuseppe Sinopoli (DG 1993)

Julian Rachlin / Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra / Lorin Maazel (Sony 1994)

Anne-Sophie Mutter / Staatskapelle Dresden / Andre Previn (DG 1995)

Vadim Repin / London Symphony Orchestra / Emmanuel Krivine (Warner 1996)

Sarah Chang / Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Mariss Jansons (Warner 1998)

Dmitri Sitkovetsky / Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields / Sir Neville Marriner (Hanssler 2000)

Christian Tetzlaff / Danish National Symphony Orchestra / Thomas Dausgaard (Warner 2002)

Akiko Suwanai / City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Sakari Oramo (Decca 2002)

Frank Peter Zimmermann / Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra / John Storgårds (Ondine 2008)

Soyoung Yoon / Gorzów Philharmonic / Piotr Borkowski (DUX 2013)

Augustin Hadelich / Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra / Hannu Lintu (Hadelich 2014)

Lisa Batiashvili / Staatskapelle Berlin / Daniel Barenboim (DG 2015)

Tobias Feldmann / Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège / Jean-Jacques Kantorow (Alpha 2017)

Ayana Tsuji / Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal / Giancarlo Guerrero (Warner 2017)

Sayaka Shoji / St. Petersburg Philharmonic / Yuri Temirkanov (DG 2018)

Christian Tetzlaff / DSO Berlin / Robin Ticciati (Ondine 2019)

Johan Dalene / Royal Stockholm Philharmonic / John Storgårds (BIS 2021)

Thank you to everyone for your patience, and I sincerely hope you enjoy Sibelius’ Violin Concerto. I hope to see you next time when we discuss Henryk Górecki’s beautiful Symphony no. 3. See you then!

_______________

Notes:

Allsen, J. Michael "Madison Symphony Orchestra Program Notes". University of Wisconsin-Whitewater. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009.

Barnett, Andrew (2007). Sibelius. Yale University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-300-11159-0.

Dotsey, Calvin. From Finland with Love: The Sibelius Violin Concerto. The Houston Symphony Program Notes. April 27, 2018. Online at https://houstonsymphony.org/sibelius-violin-concerto/.

Ginnell, Richard. Fire and ice: the best recordings of the Sibelius violin concerto. Review. 7 December 2017. Found online at https://www.thestrad.com/reviews/fire-and-ice-the-best-recordings-of-the-sibelius-violin-concerto/.

Gutman, David. Sibelius's Violin Concerto: an in-depth guide to the best recordings. Gramophone Magazine. June 6, 2022. Online at https://www.gramophone.co.uk/features/article/sibelius-s-violin-concerto-an-in-depth-guide-to-the-best-recordings.

Hillila, Ruth-Esther; Hong, Barbara Blanchard (1 Jan 1997). Historical Dictionary of the Music and Musicians of Finland. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-0-313-27728-3.

Steinberg, Michael. San Francisco Symphony Program Notes. Online at https://www.sfsymphony.org/Data/Event-Data/Program-Notes/S/Sibelius-Violin-Concerto.

Tovey, Donald Francis. Essays in Musical Analysis, 1935–39.

Woolf, Jonathan. Review Jean Sibelius Violin Concerto. Spivakovsky on Everest. Online at https://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2014/Sep14/Sibelius_VC_SDBR3045.htm.

![Janine; Klaus Makela; Oslo Philharmonic Jansen - Sibelius: Violin [New CD] - Picture 1 of 1 Janine; Klaus Makela; Oslo Philharmonic Jansen - Sibelius: Violin [New CD] - Picture 1 of 1](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!nW1P!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3f00b3e0-6fab-47e3-a78f-c980e53f6aa1_640x639.webp)

Thank you for this enjoyable blog, I'm sure it requires a lot of time and effort to write such detailed articles. So far, I have mostly agreed with your shortlists, and have also discovered some good recordings I hadn't known.

As for the Sibelius violin concerto, I couldn't help wondering about what seems to me like a notable omission: Pekka Kuusisto with Leif Segerstam conducting the Helsinki Philharmonic. I believe it's a really oustanding performance, one of the best of the many I've heard. It probably deserves at least a honourable mention. Could it be an oversight, or you just didn't like it?

Thank you John, wonderfull presentation, discussion and list of recordings, as usually.

I allow myself to suggest to add the first Lisa Batiashvili recording with Sakari Oramo and the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra on Sony. I find this version one of the best between modern version and preferable to the Barenboim’s one. Listen to the incipit of first mouvement: absolutely magnificent in my view. The qualities that you have rightly highighted of her later recording are even more recognisable here.