Building a Collection #54

La Bohème

By Giacomo Puccini

_________________

“I’m a mighty hunter of wild fowl, opera librettos and attractive women.” - -Giacomo Puccini

Welcome back to all! Number 54 on our way up to 250 is the beloved opera La Bohème by the Italian composer Giacomo Puccini. Despite some ridicule and scorn from other composers and music critics, La Bohème has remained one of the most popular operas of all-time with audiences.

Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini was born Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini in 1858 in Lucca, Italy and died in 1924 in Brussels, Belgium. Giacomo grew up in a musical family, took lessons on the organ, and sang in local church choirs. By the age of 14 he was freelancing as an organist at various churches in Lucca. In 1876, at the age of 18, he walked 18 miles from Lucca to Pisa to see a production of Verdi’s opera Aida. It cast a lasting spell on him, and he soon decided he would study composition with the goal of writing operas.

Giacomo was known to be rather lazy and disrespectful as a young man. There is the story that claims he stole the organ pipes from his church and sold them for scrap in order to buy cigarettes. Giacomo did everything at his own pace, which was not very quick. He entered Milan Conservatory in 1880. While he was recognized as having tremendous talent, he was not considered a hard-working student. A competition was held at the Conservatory, and Puccini entered a one-act opera titled Le Villi into the competition. Even though he didn’t win any prize, or even honorable mention, the famous Italian music publisher Giulio Ricordi liked the piece and deemed it worthy of being performed in Milan. The premiere took place in 1884, and was a success. Puccini’s career began to take off.

When Puccini’s mother died, he returned to Lucca for the services. While there, he fell in love with Elvira Gemignani, the wife of a local merchant. Even though his conservative family begged Giacomo to break it off and not bring shame to the family name (including one sister that was a nun), it was to no avail. Puccini ran off with Elvira, and she soon became pregnant. She gave birth to a son in 1886. Lucca was shocked by the story, and Giacomo and Elvira had to go into hiding because her outraged husband vowed revenge on them.

After the relative failure of Puccini’s next opera, Edgar, Puccini finally scored a huge success with the opera Manon Lescaut in 1893. He followed that with his three most loved and often performed works, La Bohème(1896), Tosca (1900), and Madama Butterfly (1904). Puccini embarked upon a lavish lifestyle, complete with multiple homes, cars, and designer suits and hats. Eventually he would marry Elvira after her husband died. However, other scandals ensued with Puccini reportedly often cheating on Elvira.

The saddest scandal came when Puccini was accused by Elvira of pursuing a young servant girl named Doria. Even though Puccini and Doria denied it, Elvira followed Doria and accused her of dishonor. Doria’s brothers then threatened Puccini for defiling the girl. Horrified by the allegations, the young Doria ingested disinfectant to kill herself, and died five days later. When the autopsy showed she had died a virgin, Doria’s family sued Elvira and she was convicted in court. However, Puccini paid off Doria’s family and the conviction was nullified.

Puccini had struck up a good friendship with the celebrated Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini from when Toscanini was asked to conduct the premiere of La Bohème. Toscanini went on to conduct several of Puccini’s operas. However, the two became estranged during the World War I years when Puccini seemingly took no interest in the horrors and carnage happening in the war. Toscanini was furious with Puccini for his indifference to the suffering. They broke off their friendship. Later during the Holidays, Puccini sent the traditional pannetone to Toscanini. Forgetting momentarily they were not on speaking terms, Puccini wired Toscanini: PANNETONE SENT BY MISTAKE. PUCCINI. The next day Toscanini replied: PANNETONE EATEN BY MISTAKE. TOSCANINI.

Puccini actually had very few friends, and to some extent seemed incapable of achieving the needed depth in his marriage or in other relationships. He often took more interest in playing poker, fast boats, fast cars, and fast women. It is rather remarkable that he created such profound works of emotion and passion when his personal life was somewhat empty.

Puccini, along with Verdi, are the most important composers in Italian opera. Puccini was considered to be a “verismo” composer, mirroring the Realism movement in literature at the time, where subjects, characters, and situations from everyday life were used. To be accurate, Puccini’s music is not entirely verismo, as he also used some more implausible story lines as well. His music was characterized by lush orchestration and rich, memorable melodies. Interestingly, Puccini’s music owes very little to other new or old musical influences. At times he would incorporate some ideas, but he was very much his own composer. What he possessed was an uncanny gift for melody and for enhancing the drama musically. His personal style stands out as unique. Puccini chose his librettos very carefully, and never rushed. But it is his songs and musical themes that stand out for their expressiveness.

As I mentioned in the introduction, Puccini has been criticized for using cheap emotional or dramatic effects, or for appealing to baser human instincts. Some have claimed his music is too symphonic, or too poorly developed for serious opera. There have been criticisms that his operas are too simplistic, too straightforward, not complex enough, or not intellectual enough. However, none of these critiques have mattered in the least to the audiences and opera enthusiasts. Puccini’s operas have become some of the most beloved works ever composed, and are perpetually performed in opera houses around the world.

Puccini died in 1924 in Brussels, Belgium while receiving treatment for throat cancer.

La Bohème

Bohemianism was a cultural fad of sorts in the nineteenth century. What else could explain Puccini and his fellow composer Ruggiero Leoncavallo both deciding at the same time to compose operas with the theme of Parisian starving artists? Puccini and Leoncavallo met by chance at a Milan cafe on March 19, 1893. During their conversation, Puccini mentioned he was working on a new opera, based on a libretto using Henri Murger’s Scenes de la vie de Boheme as a source, a loosely-linked series of autobiographical episodes published between 1845-1849. Leoncavallo became angry, and reminded Puccini that he was already composing a Bohème opera, and that he had previously offered the libretto to Puccini (who had rejected it).

The quarrel moved to the newspapers, where different publications announced the intentions of both composers to write operas on bohemian themes. Puccini said in a letter to the editor of the Corriere della sera newspaper in effect: “Let Leoncavallo write his opera, and I shall write mine. Then the public will decide.” And that is exactly what happened. Even though Leoncavallo’s opera was more warmly received by the critics at the outset, Puccini’s La Bohème soon became a big hit with the public and has been ever since. La Bohème would not have become the success it is without an excellent libretto. It was the first collaboration between Puccini and librettists Illica and Giacosa, and even though there were some disagreements along the way, the end result speaks for itself.

One technique Puccini uses in La Bohème is employing musical motifs to represent characters or larger themes. This was an approach made famous by German composer Richard Wagner in his operas. The touching “love” melody used for the great tenor aria Che Gelida Manina in Act I returns at the end of the act, and then again appears in Act IV as Mimi reminisces about when she first met Rodolfo. Again, Mimi’s famous aria Si, Mi Chiamano Mimi from Act I is used again at the beginning of Act III when she enters. Puccini also uses the orchestra to great effect throughout, but particularly in Act IV, note that when Mimi dies the orchestra almost drops out completely and then of course when it becomes known to everyone she has died we hear the loud minor chords played by the brass and accompanying Rodolfo’s cries of grief.

For a full synopsis of La Bohème you can go here on the Metropolitan Opera’s site: https://www.metopera.org/discover/synopses/la-boheme/.

Essential Recordings

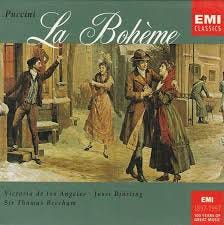

The first essential recording is one of the finest opera recordings ever made, the 1956 La Bohème led by Sir Thomas Beecham with Victoria de los Angeles and Jussi Bjorling, and accompanied by the RCA Victor Orchestra. The recording has an interesting history. The Jussi Bjorling Society explains on their site:

“The spring of 1956 brought one of those happy coincidences when every detail falls into place. It was suggested to Sir Thomas Beecham that he record La Bohème with Victoria de los Angeles as Mimì. He agreed, provided a first-class cast could be assembled. It was actually Beecham’s manager, Andrew Schulhof, who appreciated that Victoria de los Angeles, Jussi Björling and Beecham himself would all be available in New York in the spring of 1956: his suggestion to EMI and its then-associate American company, RCA, that this opportunity should be taken to record the opera, proved an inspiration. Besides de los Angeles and Björling, also the American singers Robert Merrill, baritone, Giorgio Tozzi, bass and John Reardon, baritone, were to take part.

Usually plans are made several years in advance, so that necessary stars can be brought together in one place at more or less the same time, with dates necessarily overlapping for recording the ensembles. For once, the powers-that-be moved with unprecedented alacrity, and cast, chorus and orchestra were brought together in record time. The recording sessions at the Manhattan Center began on March 16 and 17, but then were completed in an intensive rush of activity between March 30 and April 6 with only one day (April 4) left free of sessions. That is what makes Beecham’s recording of Puccini’s La Bohème – a classic of the record catalogue from the moment it was issued – even more of a miracle that it might appear on the surface.

In the middle of the recording sessions, Jussi’s back pain returned. Sir Thomas Beecham remarked that to the best of his knowledge the spine wasn’t the organ a tenor used for his singing, but his calculated sarcasm notwithstanding, the session had to be interrupted. Bob Merrill sent Jussi off in a taxi to his own chiropractor. After the treatment, similar to the one Jussi had received in Sweden nine years earlier, he rode back to the studio and continued the recording.

There was not a prior performance onstage. Sir Thomas was at his crotchety best. In the third act, de los Angeles didn’t want to cough. It would ruin her vocal line, she claimed. After the first take, when she had not coughed, Sir Thomas said, “Young lady, now we’re going to do that again, and if you don’t cough, we will later, after the tape is put together, hire a professional cougher, and you may not be able to hear a note you sing!” They did another take – and she coughed.

Legend has it that Victoria de los Angeles stopped off on her way to the airport, to make her final contribution to a recording that tingles with life and warmth from beginning to end.

In the book “Jussi”, Anna-Lisa Björling comments on the recording: “She delivered a beautiful, touching Mimì, and as Rodolfo, in my opinion, Jussi was a poet’s poet, conveying a sufficient mix of dramatic involvement, unaffected charm, and ardent lyricism. The recording has won favour with the critics, and this version of Bohème has been held up as a paragon against which all others are measured. In Jürgen Kesting’s opinion, ‘No one has sung the first act more luminously, more tenderly, and the fourth act with more restrained sentiment, than the Swede.’”

Another much-repeated legend has it that the recording was made in stereo – as it certainly ought to have been at that period – but that the stereo tape was lost or damaged, at least one act of it. The truth is that the RCA engineers – in charge of the sessions, even though EMI was the joint sponsor – did in fact use an experimental two-track technique that was also used on an RCA recording of Verdi’s Rigoletto in Rome that same year.

Whatever the technical details, the recording was processed with all speed and the finished LPs appeared on both sides of the Atlantic just before Christmas. Though characteristically some critics demurred…the verdict of record-collectors has been quite different and rightly so. This is a set which has rarely been out of the catalogue ever since, even though it is in mono only, and in purely technical terms has been supplanted many times over. Limited or not, the sound remains extraordinarily vivid.”

Beecham had known Puccini, and they had discussed La Bohème specifically in 1920 before Puccini’s death. Beecham certainly had a claim to how Puccini wanted the opera performed, as did Toscanini.

I love this recording, and will return to it often.

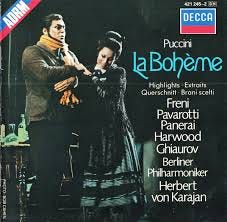

The second essential recording of La Bohème is the 1972 recording of La Boheme made by Decca with a relatively young Luciano Pavarotti as Rodolfo, Mirella Freni as Mimi, and the Berlin Philharmonic directed by Herbert von Karajan. This one has also been a classic since the day it was released. Pavarotti is in tremendous form vocally. The role of Rodolfo is marginally less suitable for Pavarotti compared to Bjorling, but the unique and ringing timbre of his voice is unforgettable. Mirella Freni is undoubtedly one of the great Mimis ever. Elizabeth Harwood as Musetta is satisfactory, though I would give the nod to Lucine Amara on the Beecham set. The Berliners and Karajan sound excellent, and overall the sound is substantially better than the Beecham set. If you love this opera, you will want to have both of these recordings.

Recommended Recordings

The NBC Symphony Orchestra from 1946 conducted by Arturo Toscanini (who conducted the premiere in 1896), on RCA taken from live radio broadcasts, remains an important and fascinating historical recording. Licia Albanese is Mimi and Jan Peerce is Rodolfo, with sound that is flawed but remarkably good for its age. This is a set to be treasured as well, although I have some trouble with Peerce as Rodolfo. For me the quality of his voice, although tremendous, is just not correct for Rodolfo. Albanese is wonderful, if old-fashioned sounding. Nevertheless, this should at least be heard for Toscanini’s vibrant and idiomatic direction.

Orchestra and Chorus of the Rome Opera House conducted by Thomas Schippers with Nicolai Gedda as Rodolfo and Mirella Freni as Mimi, recorded by EMI in 1964. This remains one of my personal favorites. Gedda sings sensitively as well as heroically as Rodolfo, and Freni is younger and perhaps more vulnerable sounding than her later recording with Karajan. I enjoy her characterization of Mimi better here. The American conductor Thomas Schippers was known particularly for his opera interpretations, and this is one of his best recordings.

Other Notable Recordings

Orchestra and Chorus of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia / Tebaldi / Prandelli / Erede (Decca / Naxos 1951)

Orchestra and Chorus del Teatro della Scala / Callas / DiStefano / Votto (Warner 1956)

Orchestra and Chorus Accademia della Santa Cecilia / Tebaldi / Bergonzi / Serafin (Decca 1959)

Orchestra and Chorus del Teatro della Scala / Gheorghiu / Alagna / Chailly (Decca 1999)

Notable Video Recordings

I will be the first to admit I am not as familiar with the DVD versions of La Bohème, but I have enjoyed viewing the ones below:

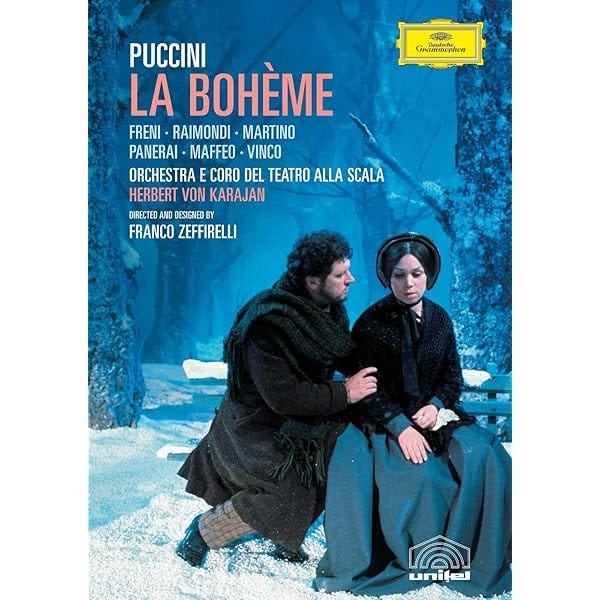

Orchestra and Chorus del Teatro della Scala / Freni / Raimondi / Karajan (DG 1965)

This filmed version of the opera from 1965 followed the acclaimed Franco Zeffirelli production in Milan from 1963 with Herbert von Karajan, Mirella Freni, and Gianni Raimondi. A few observations I made were that Karajan was a terrific opera conductor, particularly of this opera, and his direction is spot on. Freni is in tremendous form, in my view better than she was a decade later with Pavarotti on their celebrated set listed above. I was not familiar with Raimondi, but he is also wonderful and although his voice was not the equal of Pavarotti’s, his acting is better and the voice is still formidable and well-characterized. The one thing that is off-putting to me is the filming techniques are quite dated, and the voices are not synchronized with the film very well. I recommend listening to the audio without the picture because on purely musical terms this is one of the finest versions ever recorded.

Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus / Carreras / Stratas / Levine (DG 1982)

There is a lot to recommend this version taken from the Metropolitan Opera in 1982. Carreras is outstanding in the role of Rodolfo, especially his acting, even with the very subtle beginnings of some odd vocal results in the higher stave which would only worsen with his leukemia later in the decade. Teresa Stratas is beautiful as Mimi, she is very believable in her frailty but is also vocally assured. Renata Scotto as Musetta overshadows Stratas a bit, although her vibrato had widened by this time enough that I am grateful she was not cast as Mimi here. This is Zefirelli’s staging again, a long time favorite production.

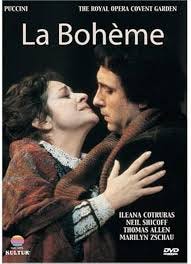

Royal Opera House Covent Garden Chorus and Orchestra / Cotrubas / Shicoff / Gardelli

The 1982 ROH production with Ileana Cotrubas as Mimi, Neil Shicoff as Rodolfo, and conducted by Lamberto Gardelli is very satisfying and captured in excellent sound (on Kultur Video). The stage production is by Brian Large. This was a wonderful surprise. I had forgotten what a vibrant and plangent voice Neil Shicoff had at the time, and he uses it powerfully but also sensitively even if his diction is not perfect. Cotrubas is a charming and engaging Mimi, even with some widening in her vibrato. Gardelli’s direction is idiomatic and dramatic.

We have reached the end of this survey of La Bohème. I hope you enjoy listening to this timeless story of love and heartbreak.

Next time we will return to Gustav Mahler, this time discussing his great vocal symphony Das Lied Von Der Erde. See you then!

____________________________

Notes:

Cummings, Robert. Hambrick, Jennifer. All Music Guide to Classical Music, The Definitive Guide. All Media Guide. Giacomo Puccini. Pp. 1038 - 1039. Backbeat Books, San Francisco. 2005.

http://www.jussibjorlingsallskapet.com/id/1385.html

Lunday, Elizabeth. Secret Lives of Great Composers. Giacomo Puccini. Pp. 152 - 159. Quirk Books, Philadelphia. 2009.

https://www.metopera.org/discover/synopses/la-boheme/

Weaver, William. La Boheme: Puccini’s Perennially Youthful Opera. Berlin Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan. 1972. Decca Liner Notes. Pp. 13-18.

Schonberg, Harold C. The Lives of the Great Composers, Revised Edition. Only for the Theater. Giacomo Puccini. Pp. 425 - 431. Norton & Company, London and New York. 1981.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jussi_Bjorling

Any thoughts on the Scotto · Poggi · Meneguzzer · Gobbi · Votto set from DG? I haven't listened, but some seem to love it -- https://www.gramophone.co.uk/features/article/the-50-greatest-classical-recordings-you-ve-probably-never-heard , https://www.deutschegrammophon.com/en/catalogue/products/puccini-la-boheme-votto-2760

Thank you