Building a Collection #41

Tosca

Giacomo Puccini

_____________

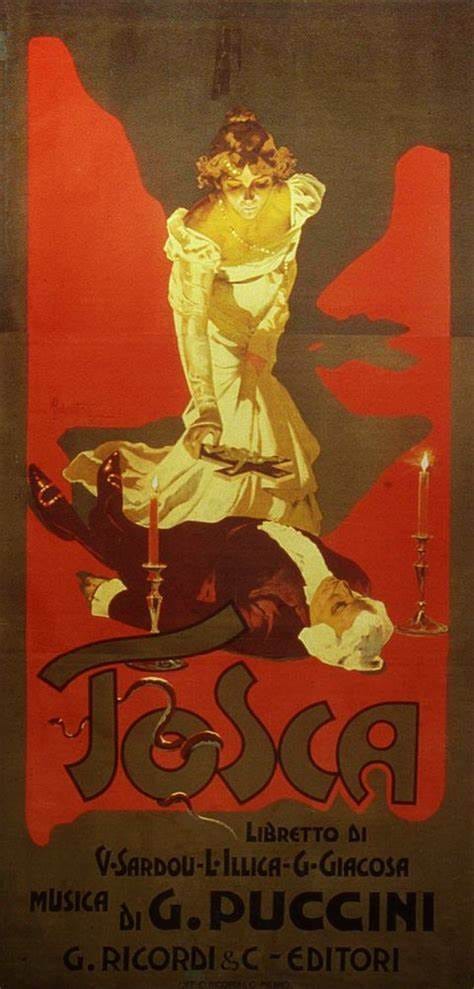

Number 41 in the Building a Collection series is the opera Tosca, the sixth opera so far on the list. Tosca is an opera in three acts by Giacomo Puccini to an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. It premiered at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome on 14 January 1900. The work, based on Victorien Sardou's 1887 French-language dramatic play, La Tosca, is a melodramatic piece set in Rome in June 1800. Along with La Boheme, it is probably one of Puccini’s most popular and enduring works.

I was first introduced to Tosca when I was living in Rome in 1991 and I was given a free ticket to see the opera at the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma. I enjoyed it so much, I bought a ticket to go back and see it again a few nights later. I remember well that in the big third act tenor aria E lucevan le stelle, the Cavaradossi sang it so well that the tenor took several curtain calls in the middle of the opera and twice went back and sang it again from the beginning. Throw in the fact the opera is set in Rome where I was living at the time, and in places I had personally visited such as the Basilica Sant’Andrea della Valle and the Castel Sant’ Angelo, and I was hooked. A decidedly dark story, Tosca’s sinister mood and drama appealed to me, along with Puccini’s prodigious melodic and lyrical gift. I absolutely loved it, and to this day it remains my favorite Italian opera.

Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini was born Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini in 1958 in Lucca, Italy and died in 1924 in Brussels, Belgium. Giacomo grew up in a musical family, took lessons on the organ, and sang in local church choirs. By the age of 14 he was freelancing as an organist at various churches in Lucca. In 1876, at the age of 18, he walked 18 miles from Lucca to Pisa to see a production of Verdi’s opera Aida. It cast a lasting spell on him, and he soon decided he would study composition with the goal of writing operas.

Giacomo was known to be rather lazy and disrespectful as a young man. There is the story that claims he stole the organ pipes from his church and sold them for scrap in order to buy cigarettes. Giacomo did everything at his own pace, which was not very quick. He entered Milan Conservatory in 1880. While he was recognized as having tremendous talent, he still was not considered a hard-working student. A competition was held at the Conservatory, and Puccini entered a one-act opera titled Le Villi into the competition. Even though he didn’t win a prize, or even honorable mention, the famous Italian music publisher Giulio Ricordi liked the piece and deemed it worthy of being performed in Milan. The premiere took place in 1884 and was a success. Puccini’s career began to take off.

When Puccini’s mother died, he returned to Lucca for the services. While there, he fell in love with Elvira Gemignani, the wife of a local merchant. Even though his conservative family begged Giacomo to break it off and not bring shame to the family name (including one sister that was a nun), it was to no avail. Puccini ran off with Elvira, and she soon became pregnant. She gave birth to a son in 1886. Lucca was shocked by the story, and Giacomo and Elvira had to go into hiding because her outraged husband vowed revenge on them.

After the relative failure of Puccini’s next opera, Edgar, Puccini finally scored a huge success with the opera Manon Lescaut in 1893. He followed that with his three best loved and most often performed works, La Boheme (1896), Tosca (1900), and Madama Butterfly (1904). Puccini embarked upon a lavish lifestyle, complete with multiple homes, cars, and designer suits and hats. Eventually he would marry Elvira after her husband died. However, other scandals ensued with Puccini cheating on Elvira repeatedly.

The saddest scandal came when Puccini was accused by Elvira of pursuing a young servant girl named Doria. Even though Puccini and Doria denied it, Elvira followed Doria and accused her of dishonor. Doria’s brothers then threatened Puccini for defiling the girl. Horrified by the allegations, the young Doria ingested disinfectant to kill herself, and died five days later. When the autopsy showed she had died a virgin, Doria’s family sued Elvira and she was convicted in court. However, Puccini paid off Doria’s family and the conviction was nullified.

Puccini struck up a good friendship with the celebrated Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini from when Toscanini was asked to conduct the premiere of La Boheme. Toscanini went on to conduct several of Puccini’s operas. However, the two became estranged during the World War I years when Puccini seemingly took no interest in the horrors and carnage happening in the war. Toscanini was furious with Puccini for his indifference to the suffering. They broke off their friendship. One year during the Holidays, Puccini sent the traditional pannetone to Toscanini. Not remembering until later they were not on speaking terms, Puccini wired Toscanini: PANNETONE SENT BY MISTAKE. PUCCINI. The next day Toscanini replied: PANNETONE EATEN BY MISTAKE. TOSCANINI.

Puccini actually had very few friends, and to some extent seemed incapable of achieving the needed depth in his marriage or in other relationships. He often took more interest in playing poker, fast boats, fast cars, and fast women. It is rather remarkable that he created such profound works of emotion and passion when his personal life was somewhat empty.

Puccini, along with Verdi, are the most important composers in Italian opera. Considered to be a “verismo” composer, mirroring the Realism movement in literature at the time, where subjects, characters, and situations from everyday life were used. To be accurate, Puccini’s music is not entirely verismo, as he also used some more implausible story lines as well. His music was characterized by lush orchestration and rich, memorable melodies. Interestingly, Puccini’s music owes very little to other new or old musical influences. At times he would incorporate some ideas, but he was very much his own composer. What he possessed was an uncanny gift for melody and for enhancing the drama. His personal style stands out as unique. Puccini chose his librettos carefully, and never rushed. But it is his songs and musical themes that stand out for their expressiveness.

Puccini has been criticized for using cheap emotional or dramatic effects, or for appealing to baser human instincts. Some have claimed his music is too symphonic, or too poorly developed for serious opera. There have been criticisms that his operas are too simplistic, too straightforward, not complex enough, or not intellectual enough. However, none of these critiques have mattered in the least to audiences and opera enthusiasts. Puccini’s operas have become some of the most beloved works ever composed and are frequently performed in opera houses around the world.

Puccini died in 1924 in Brussels, Belgium while receiving treatment for throat cancer.

Tosca

Puccini saw a performance of Sardou’s La Tosca in 1889 and eventually asked for the rights to turn it into an opera. Puccini’s publisher Ricordi obtained the rights and assigned the librettist Luigi Illica to adapt the play. Illica advised Puccini against turning the drama into an opera, as he didn’t believe it would translate well in musical terms. Puccini remained interested in it, but after Sardou insulted Puccini by saying he didn’t want an unknown Italian composer whose music he didn’t like composing the opera, Puccini withdrew from the contract. Nevertheless, Puccini still wanted to use the play later when another composer assigned to it abandoned it. In August 1895 Puccini once again gained the rights to compose the opera. The playwright Giuseppe Giacosa joined Illica to work out some of the adaptation, with Giacosa clashing with Puccini over the condensation needed to make the opera a reasonable length.

He worked on the opera for four years, as it was painstaking to take the rather dense French text and turn it into a cohesive Italian opera. Tosca is a “through-composed” opera, meaning it is entirely continuous with no thematic material being repeated, with each section sounding different. Yet all of it is weaved into a seamless whole. Puccini is praised for his orchestration and originality in Tosca, using musical themes to depict specific characters, objects, and ideas. The story includes depictions of torture, murder, and suicide and Puccini was adept at using music to reflect these extremes.

The setting for the opera is Rome in 1800, around the time of the occupation by the French. The soprano singer Floria Tosca falls in love with the young tenor artist Mario Cavaradossi. Due to his political leanings, Cavaradossi is being pursued by the morally compromised Chief of Police Baron Scarpia. After Cavaradossi is captured and jailed, Tosca tries several times to appeal to Scarpia to release her lover with no success. Scarpia attempts to use Tosca as leverage to find out more about the political opposition, and even tries a quid pro quo with her but she doesn’t fall for it. I won’t tell you the rest of the story because it would involve several spoilers, but let’s say it takes some unexpected turns. The roles in the opera are as follows:

Floria Tosca - a celebrated singer (soprano)

Mario Cavaradossi - a painter (tenor)

Baron Scarpia - chief of police (baritone)

Cesare Angelotti - former Consul of the Roman Republic (bass)

A Sacristan (bass)

Spoletta - a police agent (tenor)

Sciarrone - another agent (bass)

A Jailer (bass)

A Shepherd (boy soprano)

Soldiers, police agents, altar boys, noblemen and women, townsfolk, artisans

A complete synopsis of Tosca: https://www.liveabout.com/tosca-synopsis-724318

The opening of the opera was threatened by political and social unrest in Italy at the time, and there was even a bomb threat against the Teatro Costanzi before the premiere. By 1900 the staging of a Puccini opera premiere was a national event in Italy, and many Italian dignitaries attended the premiere. The premiere was generally a success, and reportedly there were several encores during the performance. Critical reception was lukewarm with most blaming shortcomings with the libretto. Nevertheless, the public loved it and when the opera moved to La Scala in Milan with Toscanini conducting it played to full houses every night.

Despite the huge popularity of Tosca today, we still have the famously controversial description of the opera from the American musicologist and music critic Joseph Kerman’s in his 1956 book Opera as Drama that it was a “shabby little shocker”. This echoed George Bernard Shaw’s assessment of Sardou’s play La Tosca as an "empty-headed turnip ghost of a cheap shocker". Other critics were equally harsh and dismissive, but whatever reservations there may be about the story, there is little doubt about the genius of Puccini’s music. The melodramatic plot is easy to follow, the three principal voices are given great opportunities to shine, and there are two of the greatest arias in the history of opera: Vissi d’arte (Tosca, Act II) and E lucevan le stelle (Cavaradossi, Act III). The music itself shapes the story brilliantly, and the enduring popularity of the opera tells us more than any critic possibly could.

The Essential Recording

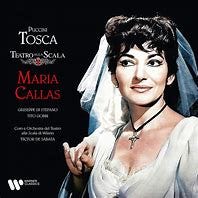

One of the top 50 classical recordings of all-time, the essential 1953 EMI mono recording of Tosca with the legendary Maria Callas as Tosca, tenor Giuseppe Di Stefano as Cavaradossi, and bass Tito Gobbi as Scarpia has never been surpassed. The exceptionally sensitive and idiomatic orchestral and choral accompaniment by Victor de Sabata and the La Scala Opera House orchestra and chorus of Milan are glorious. It was well received when it was released and has remained a bestseller for many, many years. In 2020 the recording was selected by the Library of Congress for the National Recording Registry.

But what makes this recording so special? It begins with a compelling, dramatic story as we’ve already mentioned. But what comes together here is almost perfect casting of singers for the main roles at the peak of their vocal powers. You have the greatest opera orchestra in the world at the time at La Scala in a piece they knew well, but also the vision of conductor de Sabata. De Sabata knew exactly what he wanted from the orchestra and the singers, and he was unrelenting in getting it just right. One of the greatest opera conductors of the 20th century, de Sabata made few commercial recordings. Luckily for us he recorded this one. Sadly, he died of a heart attack later in 1953 at the age of 75.

But let’s talk about Maria Callas. She was born in New York to Greek parents, but she moved back to Greece with her mother at a young age. In more recent years after her death in 1977, more people have become familiar with her due to the inclusion of the aria La Momma Morta from the opera Andrea Chenier by Giordano sung by Callas included in the acclaimed 1993 film Philadelphia starring Tom Hanks. Then in 1995 the play Master Class by Terrence McNally presented a fictional master class led by Callas in the 1970s where she teaches young aspiring singers. Callas’ personal life is a subject unto itself, as she was sometimes a difficult and temperamental personality. Aristotle Onassis was her romantic partner for many years before Onassis left her for Jackie Kennedy. The force of character may have been a detriment off stage, but it was a huge asset on stage. She possessed a unique and not entirely beautiful voice, but her understanding of how to use it and her instinctive acting ability quickly made her a star. Callas was the original “diva” for many and remains so today in her recorded legacy.

Puccini obviously never knew Callas, but if he had, the role of Floria Tosca could have been written expressly for her. Tosca was the role that brought Callas to prominence, perhaps because the quality and tone of her voice fit the role so well. Her voice has an almost shrill quality in the upper register, and yet she can also convey vulnerability and sadness. Tosca is a desperate character, and Callas plays it to perfection. The age of the recording means there is some distortion at times, and yet, that almost adds to the drama. This version of the famous soprano aria Vissi d’arte in the second act is, for me, the best it has ever been sung and that includes other renditions by Callas herself. Callas almost sobs the final few phrases, and yet she holds it together masterfully. It is somewhat fortunate that this recording was made so early in her career. Later on, especially in the 1960s, her voice began to decline, and cracks could sometimes be heard in the top notes. It was said at the time, and since, that when Callas lost a lot of weight in the mid-1950s she also lost some of her vocal power and ability to sustain notes. However, she continued to sing the role of Tosca for quite a while and audiences always clamored for it. The way she plays the character throughout Act 2, and especially her dialogues with Scarpia, is to be treasured. You viscerally feel her ferocity, and at times you may even feel sorry for Scarpia because she is a very tough customer indeed.

Giuseppe Di Stefano in the role of Mario Cavaradossi is also a pleasure to hear. His major moments are memorable to be sure, from his assured Recondita armonia in Act 1 to his glorious Victoria! Victoria! cry in Act 2 to his moving E lucevan le stelle in Act 3. There is no doubt Di Stefano was among the greatest tenors of his time, and he sang with Callas on many recordings. Reportedly he was an idol and inspiration for Pavarotti and Carreras, and he had one of the longest careers of any opera singer of the 20th century. His voice was ideal for Cavaradossi and he was only 32 years of age when he made this recording. Di Stefano’s performance here is one of the best ever recorded.

Finally, we must give a lot of credit to Baron Scarpia as sung by Tito Gobbi. Scarpia is the “bad guy” if you will of the whole story, and once again we have a voice that is tailor-made for the role. Gobbi’s voice practically snarls when needed, and it is used to great effect to genuinely make you not like him. Much has been made of the chemistry on stage and on record between Gobbi and Callas when they both played these roles, and for good reason. The strength of their characterizations is what carries the drama along so well here, and they really make you want to keep listening. The interplay between the two is so genuine and believable. Scarpia is mostly heard in Act 2, and Gobbi is brilliant at creating a sinister tone. Tito Gobbi had one of the most distinguished international operatic careers of any singer but sang the role of Scarpia almost a thousand times! Gobbi was also a close personal friend, collaborator, and admirer of Maria Callas and he noted that when performing with her he would feel as though it was actual life rather than a performance.

In summary, this is a triumph of a recording and something not to be missed. It deserves its place among the greatest recordings of all time.

Recommended Recordings

The 1959 recording of Tosca on Decca with the Italian soprano diva Renata Tebaldi as Tosca, Mario del Monaco as Cavaradossi, George London as Scarpia with conductor Francesco Molinari-Pradelli and the Orchestra and Chorus dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia of Rome is highly recommended. First the sound is typical of Decca from the era, warm and detailed. Much has been made of an alleged rivalry between Tebaldi and Callas, but there is little evidence for it. My personal preference for Tosca remains Callas, but Tebaldi had a more beautiful tone than Callas. Listening again to this recording I am struck again by how effective Tebaldi is in the role, her acting every bit as biting and effective as Callas. This is a terrific performance. Del Monaco’s opening aria is a bit inelegant in my opinion, but he gets better and better as the recording progresses. While I would not replace Di Stefano, del Monaco is superb and easily among the top handful of Cavaradossi’s on record. George London as Scarpia may be the finest of the three, bringing a large voice (he sang a lot of Wagner) which he uses intelligently and maliciously. In terms of vocal acting, London is a credible rival for Tito Gobbi and Giuseppe Taddei, and here we fully believe in the evil his character represents. In summary, this is a wonderful Tosca that deserves a hearty recommendation.

The 1962 Decca recording by Herbert von Karajan and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra features the great soprano Leontyne Price as Tosca, tenor Giuseppe Di Stefano as Cavaradossi, and baritone Giuseppe Taddei as Scarpia. This is a performance in the grand style, and it feels larger than life. Price is captured in her prime, and if she doesn’t quite match Callas and Tebaldi in her vocal acting, her ravishing, powerful tone more than compensates. Some dislike her somewhat disturbing deep chest utterances in the climactic scene with Scarpia, but I happen to really like it. Price is in the top 5 singers ever to record Tosca, and she would record it again later for RCA with Mehta (see below). There is also a live recording of her singing the role from the Metropolitan Opera also from 1962 with Franco Corelli and Cornel MacNeil on Sony much praised by the critics, but that one has some significant flaws. For me the Decca recording is Price’s finest performance of Tosca on record. Di Stefano is decidedly not as good as in the Callas set above, his voice is not as strong, and in a few places has to gather his resources just to get through it. There are even a few small cracks in his voice. But such is the strength of his characterization of Cavaradossi that he still impresses. I like Taddei very much as Scarpia, for me he joins Gobbi and London in the top tier of recorded versions in the role. He reveals a truly terrifying Scarpia, snarling and creepy. His command of the language and the role is complete. But perhaps the biggest stars of the recording are Karajan and the VPO who play with character and brilliance in the wonderful acoustic of the old Sofiensaal in Vienna. The sound is very good. This recording is a classic.

The 1976 Philips/Universal recording featuring Montserrat Caballé as Tosca, José Carreras as Cavaradossi, and Ingvar Wixell as Scarpia is outstanding. They are accompanied by the Orchestra and Chorus of Covent Garden Opera House and conductor Sir Colin Davis. While I have never been a fan of Caballé’s voice due to the somewhat matronly and fruity sound she produced at times, she is excellent here in terms of being dynamically involved in the action and at times she indeed sounds beautiful. The 29 year-old Carreras has to be my favorite Cavaradossi on record (along with Jonas Kaufmann, see below), with a truly heroic tone and none of the unpleasant tics and vocal struggles that would come into his singing later after his battle with leukemia. This performance is also preferable to his 1980 recording with Karajan, as his voice was not as good even a few years later and Karajan’s tempos are too slow. His vocal acting for Davis is superb, and his top notes are thrilling. This is a convincing performance. I don’t find Carreras and Caballé a believable match vocally in terms of their characters, but this is opera after all and we have to suspend reality a bit. Wixell is not as biting or subtle as Gobbi (who is?), but his smoothness and sarcasm brings an altogether different kind of creepy quality to Scarpia which I quite like, and his voice is secure with plenty of power. Colin Davis doesn’t get in the way of the action, and where he does underscore the drama, it feels entirely apt. The recorded sound is excellent. This is recommended as long as you can put up with Caballé (perhaps this is less of an issue for you than it is for me!).

Recommended on DVD

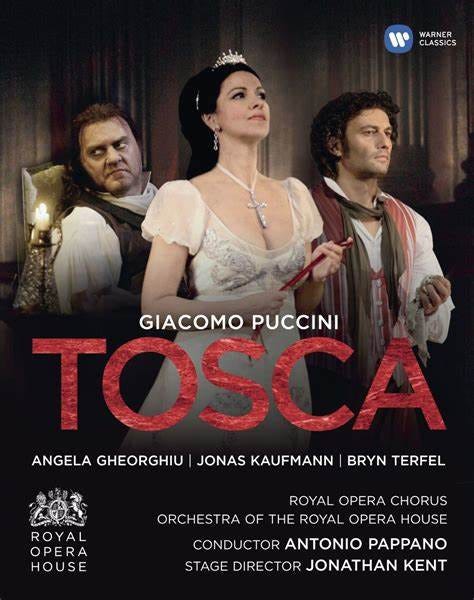

The 2011 Royal Opera House production on Warner with soprano Angela Gheorghiu in the title role, tenor Jonas Kaufmann as Cavaradossi, and baritone Bryn Terfel as Scarpia is fantastic both sonically and visually. Conductor Antonio Pappano leads the Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House. The stage production is directed by Jonathan Kent. This captures the three main protagonists near their vocal prime, and on top of that the acting is superb. The strongest of the three is Kaufmann, who is stunning as Cavaradossi. His voice has depth, range, and exceptional dynamic control to a degree I have rarely ever heard. His big numbers are nothing short of thrilling, and the unique characteristics of his voice lend something extra to the role. Even his shorter parts and dialogue are done very well. Gheorghiu is also terrific, convincing in the role (a role she has done many times), with a lot of subtlety and power when needed. In higher and louder notes there is just the slightest widening of her vibrato, but it is insignificant. Among modern sopranos she is perhaps the finest Tosca on record. The pairing of the two lovers is convincing vocally and dramatically. Bryn Terfel is outstanding as Scarpia, especially if you are able to see the video (which I easily found on YouTube). His eyes and facial expressions are priceless, and give a special character to the role. This is not merely a snarling and nasty Scarpia, but also one with shades of humor and humanity. His voice is in good form as well. I enjoyed his performance. Pappano directs an alert and sensitive account, musical on all counts, with plenty of power and drama. The staging and interpretation are essentially traditional, but by that I certainly don’t mean boring. If you are looking for a DVD of the opera, I strongly recommend this performance.

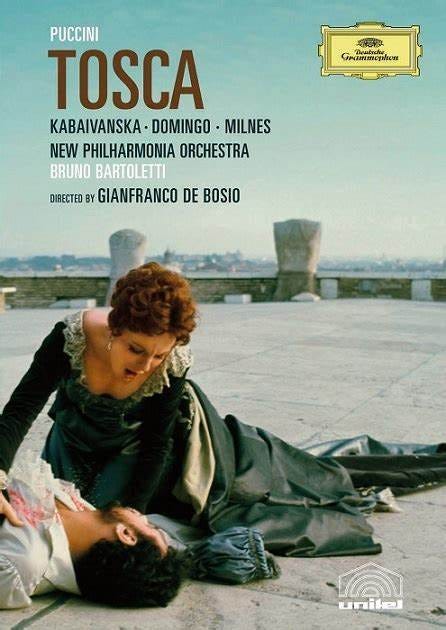

The other eminently recommendable is the 1976 film for television by Italian director Gianfranco de Bosio filmed entirely on location in Rome for Unitel (now available on YouTube and on Deutsche Grammophon). The film is extraordinarily well done for an opera on site, and the sound is quite good. Hungarian soprano Raina Kabaivanska is Tosca, tenor Placido Domingo (looking somewhat hairy and unkempt but nevermind) is Cavaradossi, and American baritone Sherrill Milnes is Scarpia. This is a special production, and well worth seeing especially since it uses the real Roman sites of the church of Sant’ Andrea della Valle (Act I), the Farnese Palace (Act II), and the top of the Castel Sant’Angelo (Act III) near the Vatican. Conductor Bruno Bartoletti leads the New Philharmonia Orchestra and the Ambrosian Singers, which sound very fine. Domingo, still only 35 at the time of this filming, is in excellent voice and his Cavaradossi is full sounding and affecting. His acting is no match for Kaufmann, but is more than adequate. Kabaivanska was 41 years of age at the time of the film, and although I was not very familiar with her, she brings great characterization to the role of Tosca and her voice is strong and expressive and compares favorably to many others that have sung the role. She and Domingo are well-matched vocally. The only small caveat is Milnes’ portrayal of Scarpia. He doesn’t have nearly the menace of other great Scarpias, and is altogether too handsome and smooth for the role. His voice and acting are fine, but he lacks the creep factor. Despite this small reservation, this is required for anyone that loves Tosca.

Other Notable Recordings

Rome Opera Chorus and Orchestra / Milanov / Bjorling / Warren / Leinsdorf (RCA, 1957)

The Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / L. Price / Corelli / MacNeil / Adler (Sony, 1962)

Conservatoire Orchestra and Chorus / Callas / Bergonzi / Gobbi / Pretre (EMI/Warner, 1965)

Santa Cecilia Chorus and Orchestra / Nilsson / Corelli/ Fischer-Dieskau / Maazel (Decca, 1966)

New Philharmonia Orchestra and John Alldis Choir / L. Price / Domingo / Milnes / Mehta (RCA, 1972)

Thank you once again for reading! I hope you enjoy Tosca as much as I do. Stay tuned as there are many more classical works to come on our list. Next up is Franz Schubert’s Symphony no. 9, the “Great”. See you then!

_______________

Notes:

Ashbrook, William (1985). The Operas of Puccini. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9309-6. tosca cast bells.

Budden, Julian (2002). Puccini: His Life and Works (paperback ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-226-57971-9.

Fisher, Burton D., ed. (2005). Opera Classics Library Presents Tosca (revised ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: Opera Journeys Publishing. ISBN 978-1-930841-41-3.

Greenfield, Edward; March, Ivan; Layton, Robert, eds. (1993). The Penguin Guide to Opera on Compact Discs. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-046957-8.

Greenfield, Edward (1958). Puccini: Keeper of the Seal. London: Arrow Books.

Jellinek, George (1986) [1960]. Callas: Portrait of a Prima Donna (revised ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-25047-2.

Nicassio, Susan Vandiver (2002). Tosca's Rome: The Play and the Opera in Historical Context (paperback ed.). Oxford: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517974-3.

Osborne, Charles (1990). The Complete Operas of Puccini. London: Victor Gollancz. ISBN 978-0-575-04868-3.

Petsalis-Diomidis, Nicholas [el] (2001). The Unknown Callas: The Greek Years. Amadeus Press ISBN 978-1-57467-059-2, issue 14 of opera biography series, foreword by George Lascelles.

Phillips-Matz, Mary Jane (2002). Puccini: A Biography. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 978-1-55553-530-8.

Tommasini, Anthony (2018). The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide. Penguin. p. 370. ISBN 9780698150133.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tosca#References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Callas

Really detailed and a pleasure to read! I do enjoy Tosca in the theatre but sometimes I come out feeling as if my emotions have been manipulated by Puccini ...