Building a Collection #37: Mendelssohn's Symphony no. 3 "Scottish"

With recommended recordings

Building a Collection #37

Symphony no. 3 in A minor, Op. 56 “Scottish”

Felix Mendelssohn

_____________

“There is but one God – Bach – and Mendelssohn is his prophet.”

-Hector Berlioz

Welcome back! Moving right along in our survey of the 250 greatest classical works of all-time, at #37 is Felix Mendelssohn’s Symphony no. 3 also known as the “Scottish” symphony. The symphony contains some of my favorite music, and it established Mendelssohn as one of the great composers.

Felix Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn (b. 1809 – d. 1847) was a German composer, pianist, organist, and conductor of the late Classical and early Romantic period. If you think you’ve never heard Mendelssohn’s music, think again. Everyone has heard the Christmas hymn Hark! The Herald Angels Sing and the melody we know for the hymn today was supplied by Felix Mendelssohn. It is quite likely you also know Mendelssohn’s other extremely famous melody, the Wedding March that is part of the incidental music from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Today Mendelssohn is known for many outstanding compositions including: A Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture and Incidental Music, “Scottish” Symphony, “Italian” Symphony, Violin Concerto, the oratorios St. Paul and Elijah, the overture The Hebrides, his Octet for strings, and his solo piano masterpiece Songs Without Words.

Felix was a child prodigy. He is often compared to Mozart in terms of his natural talent, but also because they both died far too young. Felix’s parents recognized his genius at an early age but avoided the pitfalls of touring him around and showing him off like other prodigies. Both Felix and his sister Fanny were given piano lessons, and Felix also took violin lessons. It should be noted that his sister Fanny was also very talented and was also celebrated as a prodigy. One story has Felix trying to pass off one of Fanny’s compositions as his own. Given the attitudes toward women at the time, it is perhaps not surprising that Fanny never gained the level of fame of her brother and was not encouraged to continue developing her abilities. The siblings were close. Fanny also died relatively young, and it is said that her death in May 1847 precipitated Felix’s own decline and death later that same year.

Felix grew up in a wealthy family, his father Abraham was a rich German-Jewish banker. The Mendelssohns were a well-known family as well, his grandfather Moses Mendelssohn being a famous philosopher. His father was an art lover, and it is said his mother was known to read Homer in the original Greek. Their home was comfortable and cultured. They moved from Hamburg to Berlin when Felix was very young due to Hamburg being invaded by the French. In 1822, the family converted from Judaism to Lutheranism and all four children were baptized.

Felix made such rapid progress in his lessons that the family employed the finest musical teachers of the day, and he gave his first public concert in Berlin at the age of nine. He came to the attention of such German luminaries as the composer Karl Maria von Weber and the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. At the age of 17, Mendelssohn composed his Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, an astonishingly mature composition for such a young man. Felix had studied the works of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven intently, but quickly developed his own style.

One of Mendelssohn’s most enduring legacies involves his role in the revival of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. In 1829 at the age of 20, himself already an accomplished pianist, composer, and conductor, he organized a performance of one of Bach’s greatest works, the St. Matthew Passion. This sparked a renewed interest and appreciation of Bach’s music, and since then Bach has never needed a revival. Soon after, Mendelssohn became the music director of the Gewandhaus Orchestra of Leipzig and became the foremost conductor of his day. He continued composing, while also working as a conductor, pianist, organist, and teacher. Unlike many composers, he was well regarded during his own lifetime.

Mendelssohn was one of the most complete musicians in history, but that very fact at times worked against him with the critics. Because he was so talented in many areas, he never fully reached the heights of the greatest composers. He was truly a Renaissance man, also being an outstanding visual artist, and a connoisseur of literature and philosophy. Some have commented on how his music lacks the emotional depth of Beethoven or even his contemporaries Schubert and Schumann. Mendelssohn was a rather restrained and cautious composer. He is quoted as saying to his sister Fanny, “Do not commend what is new until it has made some progress in the world and acquired a name, for until then it is a mere matter of taste.” He adhered more closely to Classical traditions and was not original in an unconventional sense such as Berlioz or Liszt. Nevertheless, Mendelssohn’s distinct musical sophistication, his gift for melody, his genius at writing for various instruments of the orchestra, and his ability to paint colors in his music, has endeared him to the listening public. His music is often lighthearted, ebullient, and graceful. Toward the end of his life, his compositions became more emotionally expressive as you can hear in his Symphony no. 3 “Scottish” and especially the oratorio Elijah.

Some of Mendelssohn’s musical conservatism may have been related to his Jewish heritage, especially in anti-Semitic Berlin. He may have been anxious not to offend the establishment and to be accepted. Another possibility is he felt his German nationalism strongly and was justly proud of the German musical tradition he inherited. In any case, he was typical of the wealthy German bourgeoisie of the time. Felix was refined, well-bred, cultured, tended to be rather snobbish, and preferred a quiet family life with his wife and children later in life.

It is quite unfortunate that Mendelssohn’s music largely declined in popularity in German during the early twentieth century. Germans seemed to focus on his Jewish roots, even though he lived virtually his entire life as a Christian. The avowed and vitriolic anti-Semitic composer Richard Wagner dismissed Mendelssohn’s work repeatedly. By the time of the Nazis, Mendelssohn had been nearly eliminated from German musical history due to his Jewish roots. His statue in Leipzig was removed and sold for scrap. It was only after the war that Mendelssohn’s music was gradually revived and later celebrated in Europe and North America.

Symphony no. 3 “Scottish”

During Mendelssohn’s first visit to England when he was 20 years of age, he also visited Scotland. While visiting Edinburgh, he wrote a letter home to his sisters in July 1829:

“We went today in the deep twilight to the Palace of Holyrood, where Queen Mary lived and loved…The chapel is roofless, grass and ivy grow abundantly in it; and before the altar, now in ruins, Mary was crowned Queen of Scotland. Everything around is broken and mouldering, and the bright sky shines in. I believe I found today in that old chapel the beginning of my Scottish symphony.”

The resulting symphony was the third to be published, hence the numbering. However, it was actually the last symphony to be composed by Mendelssohn. Although he had begun composing it shortly after his trip to Scotland, he set it aside until 1841 when he found himself in a similar sort of mood to take it up again. He completed it in 1842, and it was first performed later that same year in Leipzig, then subsequently had a very successful premiere in England. Mendelssohn requested permission to dedicate it to Queen Victoria, which was granted.

Each movement is designed to move directly into the next one without a break, unique to Mendelssohn’s symphonies. Mendelssohn also made indications on the score on the character that should be reflected in the music, including his impressions of the Scottish landscape.

The movements progress as follows:

I. Andante con moto — Allegro un poco agitato

II. Vivace non troppo

III. Adagio

IV. Allegro vivacissimo – Allegro maestoso assai

The main theme that opens the symphony recurs at other times as well. It may be described as somewhat melancholy and somber. The second movement is a scherzo that is brilliantly conceived and executed, sparkling and fleet. For me, this is one of Mendelssohn’s best creations. The third slower movement may be considered a reflection of the bleakness of Holyrood Palace, or perhaps the stark nature of the Scottish landscape. The finale is direct and furious, almost like a battle being fought. It gives way in the closing section to a boisterous and rousing song of triumph complete with brass fanfares and a fittingly grand conclusion.

Essential Recording

The essential recording of Symphony no. 3 “Scottish” is by the London Symphony Orchestra led by Peter Maag on the Decca label. The symphony was recorded in 1960. This is a classic Decca recording from the 1960s at Kingsway Hall in London, with extraordinary sound for its age, both detailed and warm.

The Swiss conductor Peter Maag (b. 1919 – d. 2001) was a sort of maverick of the classical music world. While attending university as a young man, he was equally called to study Music as well as Philosophy and Theology. Among his Theology and Philosophy professors were none other than the famous theologians Karl Barth and Emil Brunner, and philosopher Karl Jaspers. He studied piano in Paris with Alfred Cortot (among the greatest interpreters of Chopin’s music ever), and he studied conducting with Ernest Ansermet and Wilhelm Furtwangler (both legendary conductors of the twentieth century). Maag would later say his association with Furtwangler was the most important of his life because Furtwangler encouraged him to make the switch from pianist to conductor.

Over the course of his career Maag held conducting posts in Dusseldorf, Bonn, Vienna Volksoper, Parma, Turin, Padua and Veneto, and Madrid. Maag was particularly drawn to opera and became known especially for his interpretations of the Mozart operas. He conducted at Covent Garden in London, the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and the Glyndebourne Festival Opera in the UK. He also made guest conducting appearances all over the world.

From 1962 to 1964, Maag left the musical world and embarked on a personal religious retreat. Feeling he was losing touch with his spiritual self, he said “I decided it was time to retire because I was having too much success.” He had planned to only spend a few months away, first turning to the Greek Orthodox Church, and then later retreating to a Buddhist monastery near Hong Kong. The few months turned into two years. When Maag attempted to return to conducting, he discovered the time away made it quite difficult to return.

Maag became quite known for his vivid interpretations of Mendelssohn’s symphonies. What makes this recording special is the full-throated, uninhibited sound Maag draws from the LSO. The brass in particular are captured very well. There is a freshness and alertness which brings forth a sense of spontaneity. Maag pays very close attention to the dynamic tension between the soft and loud passages, as well as the shifts from slower to faster passages. Sample the first movement of the symphony at 4 '30 when it goes from Andante (moderately slow) to Allegro (brisk), and then again at 12' 00 when it goes into Assai (very fast). Those changes are handled so well, and the orchestra is on top form.

The second movement Scherzo is taken at a perfect clip, not too fast and not too slow. The tension builds with alternating softer and louder sections with the horns, trumpets, and woodwinds all making excellent contributions. Finally, the climax is reached at 2’55 in the movement when the dance hits the peak. It is a sunny, exuberant piece.

You hear another of those tempo and mood shifts at 6 '57 in the finale when the Allegro maestoso assai begins. We change into a major key, and it is almost an entirely different section tacked on to the symphony which takes up a big, triumphant tune complete with horns braying and trumpets blaring. I always look forward to this ending, no matter how many times I’ve heard it played. In this recording, the horns play for their lives and the swell they put into the notes toward the end are thrilling. Maag clearly brings the horns forward at the end, and the impact it makes is undeniable. I haven’t heard another recording of this symphony that comes close.

Other Recommended Recordings

The recordings listed below are confidently recommended and are listed chronologically by recording date.

Leonard Bernstein’s earlier recordings with the New York Philharmonic for CBS/Columbia are generally preferable to his later remakes, and such is the case with the Scottish symphony. There is a palpable sense of urgency to this 1964 recording, with tempos that intuitively feel correct. The inherent drama of the first and last movements is brought out strongly, and the second movement Vivace non troppo is ideal for Bernstein’s extrovert treatment. The concluding coda is appropriately rousing.

If you like your Mendelssohn in the grand manner, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Herbert von Karajan on the Deutsche Grammophon label (1971) is a very good choice. There is plenty of weight and precision, and as a whole the reading has tremendous sweep and impact. The Adagio is perhaps slower than normal and threatens to grind to a halt but is beautiful in its own way. The acoustic for the recording is a bit too reverberant for my liking, but the BPO strings and brass blaze through an inspired performance.

The German conductor Christoph von Dohnányi, now 94 years of age, recorded the Scottish symphony a few times, but it is his 1979 recording on Decca with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra which makes the recommended list. Dohnanyi is always reliable, if rather traditional, but his complete set of the Mendelssohn symphonies is one of the best available. The VPO sounds glorious and the rich Decca recording from the Sofiensaal in Vienna is top notch. Details abound and all sections of the orchestra can be heard well. Dohnanyi is not in a rush, but neither does he drag. In the concluding section, the horns and trumpets can be heard equally well, one point I am fussy about in this symphony.

I am a big fan of the recordings that came from Herbert Blomstedt’s tenure with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, and I believe Decca did some of their best early digital recordings there. Blomstedt’s 1992 recording of the Scottish with the SFSO is superb, details burst forth, and there is energy, virtuosity, and drive. Blomstedt is one of the most underrated conductors ever in my book, and even though his general approach is traditional, there is an extra spark here that carries the listener along. The opening Andante - Allegro is powerful and dark, the Vivace is delightful, the Adagio is reflective but doesn’t lag, and the finale is enthralling and rousing. The horns and trumpets in the coda are simply the best of any recording. A triumph among recordings of this masterpiece.

Dutch period-instrument conductor Frans Brüggen also recorded the Scottish symphony more than once, but it is his 1997 account for Philips (now Decca) with the Orchestra of the 18th Century (a group he co-founded) that really crackles. Brüggen has always been one of my favorite period-instrument and historically informed conductors, mostly because he never insisted on ridiculously fast speeds like some others. Here he leads a lively and bright performance in very good sound, and while we hear some of the typical period inflections and timbres, dynamics and tempi are handled very well in my opinion, and the sound from the strings and woodwinds is fuller than some other period performances. Quite enjoyable, and far preferable to his later recording on Glossa.

Italian conductor Riccardo Chailly released an album in 2009 titled Mendelssohn Discoveries on Decca, performed with the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, the orchestra he led from 2005 until 2016. It includes a rousing account of the Scottish symphony using the original score (today we usually hear Mendelssohn’s revised score). You may notice a few minor differences, but it is mostly the same. But the performance itself is lively and precise, Chailly pushes forward at every opportunity and the orchestra responds well. The Leipzig Gewandhaus gave the premiere of the symphony, and here they really play as if they own it. The sound is excellent.

English conductor Edward Gardner recorded all the Mendelssohn symphonies with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra for the Chandos label. The Scottish recording dates from 2013. Gardner’s approach is relatively traditional and straight forward, but he infused the music with life using slightly faster tempos. There is an organic sense that the music simply flows, and even with the quicker tempos it never feels too fast. Gardner emphasizes the rhythmic inflections, and they feel very natural in his hands. It is clear he is in sync with the orchestra at all times. The push forward in the closing bars is thrilling. Altogether very satisfying.

One significant surprise in my most recent survey of all the Scottish recordings was the one by the German clarinetist, composer, and now conductor Jörg Widmann and the Irish Chamber Orchestra on the Orfeo label. Recorded in 2014, this is great stuff with crisp and sprightly playing from the Irish orchestra. Rhythms are pointed and emphasized with fleet tempos and outstanding woodwind and brass contributions. The Vivace non troppo sizzles with life, and the transition to the coda in the finale is handled well. Horns and trumpets alternate back and forth triumphantly in the final bars. This Widmann recording was a real find.

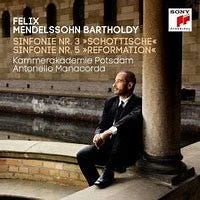

Italian violinist and conductor Antonella Manacorda has led the Kammerakademie Potsdam (in Germany) since 2010. He recorded all the Mendelssohn symphonies with the band, and the Scottish dates from 2016 on the Sony label. This is stylish, expressive, and dynamically fresh Mendelssohn. It is unclear if the Potsdam group uses period or modern instruments, but the sound bears all the hallmarks of historically informed practice with little vibrato, some rustic sonorities, and brisk tempi. This leads to greater transparency too, which brings benefits. Manacorda, more so than many other HIP conductors, pays attention to the overarching structure of the symphony. He is able to build tension wonderfully, and this brings excitement. At the same time, he pulls back when needed and never goes over the top. There is a fullness to the strings and brass that I enjoy as well.

Estonian-American conductor Paavo Järvi has been the chief conductor of the Tonhalle Zurich Orchestra since 2020, and just in 2024 he recorded all the Mendelssohn symphonies for the Alpha label. Järvi employs some historically informed practices (something the Zurich orchestra did a lot when led by David Zinman), but this feels appropriate with the more classically shaped Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn also seems to suit Järvi better than some of the more romantic composers, at least to my ears. Tempos are quick, but certainly in line with recent recordings, and the orchestra plays marvelously across the board. The greater transparency is appealing too, and even with that Järvi elicits a lot of color and atmosphere. There is plenty of drama, and the sizzling coda in the finale is terrific. After my disappointment with Järvi’s Tchaikovsky set from Zurich, he has redeemed himself.

Other Recordings of Note

London Symphony Orchestra / Claudio Abbado (DG, 1985)

The Cleveland Orchestra / Christoph von Dohnanyi (Telarc, 1988)

London Philharmonic Orchestra / Franz Welser-Möst (Warner, 1992)

The Chamber Orchestra of Europe / Nikolaus Harnoncourt (Warner, 1992)

Netherlands Symphony Orchestra / Jan Willem de Vriend (Challenge, 2013)

London Symphony Orchestra / Sir John Eliot Gardiner (LSO Live, 2014)

Freiburger Barockorchester / Pablo Heras-Casado (HM, 2015)

The Chamber Orchestra of Europe / Yannick Nézet-Séguin (DG, 2017)

That’s all folks for this edition of Building a Collection. Next time we will turn our attention to #38, Edward Elgar’s Variations on an Original Theme, Op. 36, also known as his Enigma Variations. I am looking forward to it! See you then.

_____________

Notes:

Dettmer, Roger. All Music Guide to Classical Music, The Definitive Guide. All Media Guide. The Hebrides. Pp. 823. Backbeat Books, San Francisco. 2005.

Goulding, Phil G. Classical Music, The 50 Greatest Composers and Their 1000 Greatest Works. Felix Mendelssohn (1809 – 1847). Pp. 220-229. 1992.

Lunday, Elizabeth. Secret Lives of Great Composers. Felix Mendelssohn. Pp. 74-80. Quirk Books, Philadelphia. 2009.

Newman, Bill. Peter Maag Conducts Mendelssohn. London Symphony Orchestra, Peter Maag. 2000. Decca “Legends” Liner Notes. Pp. 4-5.

Palmer, John. All Music Guide to Classical Music, The Definitive Guide. All Media Guide. Symphony no. 3 “Scottish”. Pp. 822. Backbeat Books, San Francisco. 2005.

Schonberg, Harold C. The Lives of the Great Composers, Revised Edition. Bourgeois Genius Felix Mendelssohn. Pp. 216-217. Norton & Company, London and New York. 1981.