Building a Collection #36: Debussy's Clair de Lune

With recommended recordings

Building a Collection #36

Clair de Lune

By Claude Debussy

________________

Welcome back everyone! We are at #36 on our list of the 250 greatest classical works of all-time and coming in at 36 is probably the shortest piece on our survey, the iconic piano piece Clair de Lune by French composer Claude Debussy.

Claude Debussy

The French composer Achille-Claude Debussy was born in 1862 and died in 1918. Debussy is sometimes referred to as the first “Impressionist” composer. Impressionism in music was a movement among various composers in Western classical music (mainly during the late 19th and early 20th centuries) whose music focuses on mood and atmosphere, conveying the moods and emotions aroused by the subject rather than a detailed tone‐picture. "Impressionism" is a philosophical and aesthetic term borrowed from late 19th-century French painting after Claude Monet's Impression, Sunrise. Composers were labeled Impressionists by analogy to the Impressionist painters who used starkly contrasting colors, light effects on an object, blurry foreground and background, flattening perspective, etc. to make the observer focus their attention on the overall impression.

Even though Debussy and fellow French composer Maurice Ravel are considered the foremost figures in Impressionist music, Debussy completely rejected the label to describe his own music, declaring in a 1908 letter: "imbeciles call what I am trying to write 'impressionism', a term employed with the utmost inaccuracy, especially by art critics who use it as a label to stick on Turner, the finest creator of mystery in the whole of art!" Fair or not, this categorization has persisted for Debussy’s music. You can decide for yourself.

Debussy in some ways was the quintessential “bohemian” artist. Despite being recognized as having great talent at a young age (entering the Paris Conservatory at age 10), Debussy would often skip classes or produce work that was careless. Although he was a charming young man, he was less than diligent in his studies, and he quite enjoyed the cafe life. In 1880 he accepted a position playing piano for the family of Nadezhda von Meck (von Meck is better known as the wealthy patroness of Tchaikovsky) and during his time traveling with the family, he developed a taste for luxury that would last throughout his life.

Amid a series of questionable romances and dalliances with various older women, Debussy also earned the scorn of some of his professors because he refused to follow the orthodox rules of composition then prevailing. In 1885, Debussy wrote of his intent to follow his own path commenting, "I am sure the Institute would not approve, for, naturally it regards the path which it ordains as the only right one. But there is no help for it! I am too enamored of my freedom, too fond of my own ideas!" Despite his intransigent views on composing, he was awarded France’s most prestigious award in 1884, the Prix de Rome, for his cantata L'enfant prodigue. The prize came with a two-year stint at the Villa Medici to study at the French Academy in Rome. Although the time in Rome was not too productive, when he returned to Paris he attended a performance of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde which he instantly loved. While Debussy greatly admired Wagner’s subjects and harmonic inventiveness, he would ultimately reject Wagner’s symbolism and indeed Debussy’s music is often seen as a reaction against Wagner’s music and his uber-Teutonic vision.

Around 1900, Debussy's music became an inspiration for an informal group of innovative young artists, poets, critics, and musicians who began meeting in Paris. They called themselves Les Apaches (loosely “The Hooligans”) to represent their status as artistic iconoclasts. The group was fluid, but at various times also included Maurice Ravel, Ricardo Viñes, Igor Stravinsky and Manuel de Falla.

In his private life Debussy was impulsive, rather thoughtless, and even cruel. In 1903 Debussy taught a young man named Raoul Bardac, son of Emma and Parisian banker Sigismond Bardac. Raoul introduced Debussy to his mother, and Debussy was immediately infatuated with her. Emma was an intellectual equal to Debussy, an excellent singer, and had no qualms about breaking her marital fidelity. Debussy sent his then wife Lilly to stay with her parents so he could spend time with Emma. A short time later he wrote to Lilly that their marriage was over, and upon return to Paris Debussy and Emma set up their home in a different section of Paris. In October 1904, Lilly attempted suicide, shooting herself in the chest with a revolver. She survived, with the bullet lodging in her vertebrae. The scandal caused Bardac’s family to disown her, and Debussy’s standing with many good friends (including Ravel) and the public suffered greatly. After the Bardacs divorced, Debussy and a pregnant Emma moved to England for a while, but eventually moved back to Paris where Debussy would spend the rest of his life.

Debussy often took inspiration for his compositions from literature and art. A big step forward in his musical output was the 1894 symphonic poem Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, based on Stéphane Mallarmé's poem. It was to become one of his most popular and enduring works. His only opera Pelleas et Melisande (premiered in 1902), based on a play by Maurice Maeterlinck, became his first great success, his confidence in his craft was growing, and he embarked upon a very productive period. Other Debussy works which solidified his reputation include the orchestral works Nocturnes for Orchestra (1899), Images (1905-12), and La Mer (1903-05). His works for piano also led to fame and notoriety, and works such as Two Arabesques, Suite Bergamasque (see below), Préludes (1909-13), and Études (1915) remain popular today and are often recorded.

Debussy’s musical legacy has been widely debated in scholarly circles. Debussy wrote "We must agree that the beauty of a work of art will always remain a mystery [...] we can never be absolutely sure 'how it's made.' We must at all costs preserve this magic, which is peculiar to music and to which music, by its nature, is of all the arts the most receptive.” Some musicians and critics see Debussy as a trailblazer in that he created new tonalities, and that he did more to advance “modern” music than any other composer. Debussy liked to experiment with melodies and harmonies, and without getting too deep into music theory, Debussy was fond of using melodic tonalities with unusual harmonies which were quite different from what was conventional at the time, especially given the huge shadow of German musical tradition. The sequences of chords Debussy often used were more experimental and did not follow any particular theory. That is not to say there was no structure, but Debussy demanded absolute freedom to alter conventional rhythms, colors, dynamics, and harmonies if it fit his purpose. Having said that, one hears in Debussy’s music echoes of other prominent composers of the time including other fellow French composers Charles Gounod, Emmanuel Chabrier, Jules Massenet, Erik Satie (a good friend), as well as Russian composers Mikhail Glinka, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Alexander Borodin, Modest Mussorgsky, and even Tchaikovsky. But Debussy revered Frédéric Chopin above all other composers, especially for what Chopin accomplished with the piano. Chopin influenced Debussy’s piano works, although Debussy definitely developed his individual voice. Debussy reacted against realism and objectivity in his work, and so his compositions increasingly depict subjective moods, and avoid detailed descriptions of reality or opinion. Keep that in mind as you listen to Clair de Lune.

Clair de Lune

Clair de Lune is the third movement of a piano suite titled Suite Bergamasque, but Clair de Lune itself is often played separately from the suite and is one of the most popular and famous pieces of music ever composed. Suite Bergamasque was probably begun as early as 1890 but was significantly revised before publication in 1905. Debussy had achieved quite a bit of fame in the intervening years, so how much of it was from the earlier period and how much was revised later we don’t know.

Clair de Lune was not the original name of the third movement, but rather Promenade sentimentale (A sentimental stroll). The names of the movements and at least some of the themes come from poems by Paul Verlaine, including Verlaine’s poem Clair de Lune. Verlaine was a poet of the Symbolist era. The Symbolist movement was a late 19th Century movement which originated with a group of French writers and poets and eventually spread to paintings, to the theatre, and eventually to music. The Symbolists sought to convey individual emotional experience through the use of subtle, suggestive, and highly metaphorical language for the symbol in place of the reductionist, literal or universal meaning used in conventional writing or art. Concrete representation is replaced with more imaginative meaning based upon mood, myth, or atmosphere. Debussy was quite drawn to Verlaine’s symbolist work, and Clair de Lune is certainly reflective of this movement.

Clair de Lune is in D-flat major and is marked andante très expressif (very expressive andante). The title means “moonlight”, which is certainly apt, but you may find that Debussy’s original title of Promenade sentimentale may actually be more descriptive of your experience of the music. That is what is unique about Debussy’s music in general and Clair de Lune in particular, as the music itself is a journey through one’s personal emotions and everything is open to interpretation; each listener must pay attention to their own sentiments raised by the music and make personal connections rather than being told what to feel by the composer. Clair de Lune stirs up many emotions, some that we were unaware of or cannot explain, and these feelings differ from person to person. Words don’t always do justice to how this music makes us feel, but some words that may be associated with it include dreamy, floating, sad, lonely, fluid, mellow, relaxing, reflective, ambiguous, comforting, charming, veiled, sorrowful, atmospheric, pictorial, delicate, luminous, touching, contemplative, wistful, mysterious, timeless, blurry, and deep. My own emotions stir between wistful and hopeful, desolate and resigned, sad and grateful. What do you feel when you listen to Clair de Lune?

One of the features of Clair de Lune is the instruction from Debussy for it to be played with “tempo rubato”, meaning the pianist is allowed the freedom to speed up and slow down at their discretion. Debussy felt strongly that the performer should have the freedom to use rhythmic ambiguity and that there should be “a general flexibility” rather than playing too strictly in time. Debussy also encouraged liberal use of the pedal on the piano to create vibrating overtones to add to the overall atmosphere of the piece. At the central climax, Debussy advised for the pianist to not exaggerate the dynamics, but rather to keep the expression dignified. The flow should be fluid, mellow, and drowned in pedal.

Some scholars believe that in Suite Bergamasque Debussy was paying homage to the ancient style of music from the golden age of the French Baroque from the 17th and 18th centuries, composers such as François Couperin and Jean-Phillipe Rameau. This goes along with Debussy likely pushing back against the pomposity of Wagner and perhaps intentionally emphasizing the “French” nature of his music at a time when Germany was increasing its militarization and agitation against France. Although Debussy’s music doesn’t sound like baroque music at all, he greatly admired the composers of the French renaissance and baroque periods.

Recommended Recordings

Up front I must admit to some biases when I listen to recordings of Clair de Lune. First, the pianist’s touch, subtlety, and delicacy are of the utmost importance. A pianist that pounds their way through the piece, plays too loudly, is recorded too closely, will not do. Second, although recorded versions of Clair de Lune range from around 4 minutes to about 7 minutes, taking it too fast or too slow will also not do. Pianists that are too “metronomic” in their playing, that display little flexibility in tempo, or too little elasticity in phrasing, in my view do not bring out the necessary color and sentiment in the piece. A sweet spot for timing is between 5 and 6 minutes, though there are a few very fine recordings which fall outside of those timings.

I have not identified an absolutely essential recording of Clair de Lune which rises above all the rest. But the recordings below rank highly in my estimation. The recordings are listed in chronological order by recording date.

German piano legend Walter Gieseking was seemingly an effortless Debussy interpreter, recording all the piano works for EMI/Warner, with his Clair de Lune being released in 1954. There is a captivating, almost whimsical quality to Gieseking’s playing which brings excitement, but it is also completely transparent. At times he seems to evoke a dreamy landscape, and the sound he produces is delicate and ethereal. This is a wonderfully satisfying Clair de Lune.

Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter recorded Clair de Lune as part of a live recital in October 1960 at Carnegie Hall in New York which was recorded by Columbia (now Sony). The sound is quite poor actually, but good enough to hear the magic Richter spins with Clair de Lune. Debussy is not a composer I associate with Richter, but such was Richter’s genius that he could play nearly anything at the highest level. His authority is there, but what really impresses me is Richter’s deft touch and sensitivity. He is able to pull all the strings. A great historical document if you can tolerate the subpar sound.

The 1984 recording on Philips by Hungarian pianist Zoltán Kocsis has been reissued a few times by Philips (now Decca) on collections of Debussy’s solo piano music by Kocsis. All of Kocsis’ Debussy recordings are very good, but I was quite close to making his version the essential Clair de Lune. Kocsis’ ability to use both hands in such a complementary way enhances the color and brilliance of the piece, but Kocsis is also in tune with the fluidity of dynamics and tempo in such a way that the emotional pulse of the work comes forth easily. Paced beautifully, this can be confidently recommended.

Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau was a master of color, shading, and touch and it is these qualities he brings to his 1991 recording of Clair de Lune on Philips (Universal) as part of his “Final Sessions” series. Arrau is slower than most, but his resplendent and rich tone is sumptuous and Arrau’s ability to weave the phrases into a cohesive whole without rushing is impressive. This is playing that allows the music to unfold naturally without mannerism, but with great sensitivity.

French pianist Pascal Roge has recorded Clair de Lune twice, but it is his first account for Decca from 1994 that has been one of my favorites for many years. You will notice right away that the piano is distantly recorded, the recording level being low. While initially off-putting, upon further listenings I have concluded this distant sound actually enhances the interpretation by creating a sense of atmosphere. What is amazing to me is Roge’s utterly delicate and light touch on the keys, which reflects nearly perfectly my own idea of how it should be played. There is a luminous and subtle quality to Roge’s playing that has rarely been matched. Superb.

English concert pianist Gordon Fergus-Thompson was an unfamiliar name to me before I heard his Clair de Lune. But I am convinced that his 1997 recording on ASV is one of the finest. Fergus-Thompson has a full tone, but a fine touch as well, and he brings a lot of color to his phrasing. Although somewhat measured, Fergus-Thompson is able to hold the listener’s attention marvelously. I thoroughly enjoyed it. His entire Debussy set is recommended.

The accomplished French pianist Jean-Efflam Bavouzet recorded a splendid Clair de Lune in 2008 for Chandos, and even though his account is somewhat brisker than my personal preference, this is a terrific interpretation. Bavouzet’s playing is assured and chooses tempos which tread a middle ground between over expressivity and under characterization. The beginning is a bit quick, but I love how Bavouzet dramatizes the central section where he brings out the tension and emotion very well. The final section returns to the beginning mood, perfectly bookending the piece. This recording convinced me that a somewhat quicker pace can be equally moving and satisfying.

The young American Israeli pianist Inon Barnatan greatly impressed me with his recordings of the Beethoven piano concertos, and his 2010 recording of Clair de Lune (on an album titled Darknesse Visible) for Pentatone is equally impressive. Indeed, this recording was also a candidate for the essential slot, as Barnatan’s playing has much thoughtfulness, refinement, and delicacy. He combines his prodigious technical talent with a lyrical sensibility that captures just the right mood for this piece. Barnatan is not one to inject himself into the music, and what I hear on this recording is a pianist putting himself at the service of the composer. A wonderful recording.

The brilliant young South Korean pianist Seong-Jin Cho recorded Clair de Lune in 2017 for Deutsche Grammophon as part of an all-Debussy album. Cho has a poetic sensibility, and his Suite Bergamasque is the best thing on the album. His nuanced playing is full of light and shade, as well as stylish lyricism. If Cho doesn’t quite bring the depth of Roge or Geiseking, his playing is beyond reproach and the imagery evoked by his playing is moving.

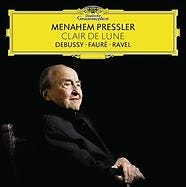

Finally, we have the 94-year-old Israeli American pianist Menahem Pressler recording Clair de Lune for Deutsche Grammophon in 2018 (Pressler passed away in 2023). This is a slower account, but with Pressler we hang on every note, such is his ability to place notes carefully, change dynamics in subtle ways, and make the notes almost float. This is a completely “felt” approach, dispensing with any semblance of routine in order to create a dreamy, suspended sound world which serves Debussy quite well. Pressler is a master here, and I just love his sentimental approach.

Other Recordings of Note

Aldo Ciccolini (Warner, 1964)

Tamás Vásáry (DG, 1969)

Kathryn Stott (Sony, 1987)

Leon Fleisher (Sony, 2004)

Nelson Freire (Decca, 2008)

Angela Hewitt (Hyperion, 2011)

Steven Osborne (Hyperion, 2022)

Honorable mention goes to Japanese electronic music pioneer Isao Tomita for his synthesizer version from 1974, by far Tomita’s most popular download on Spotify. It was used at the closing ceremony at the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo (in 2021) as an acknowledgement of Paris as the next host city and a prayer for peace before the Olympic flame was extinguished.

I apologize for the length of this post, but I am grateful for your readership. Join me next time when we discuss #37 on our list, Felix Mendelssohn’s Symphony no. 3 “Scottish”. See you then!

________________________________________

Notes:

Baldrick, Chris. "Symbolists", The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, Oxford University Press, 2015, retrieved 13 June 2018 (subscription required)

Burkholder, J. Peter. Grout, Donald J. and Palisca, Claude V. A History of Western Music, eighth edition (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010). ISBN 978-0-393-93280-5.

Cindy34612349. How Debussy’s ‘Clair de Lune’ makes us feel. Thenotesofscience: A nerdy approach to music. July 10, 2014.

Debussy, Claude (2007). Debussy: Favorite Piano Works. New York, NY: G. Schirmer. pp. 185–211. ISBN 978-1-4234-2741-4.

Duchen, Jessica. Debussy’s ‘Clair De Lune’: The Story Behind The Masterpiece. UDiscovermusic.com. March 25, 2024.

"From L'aprés-midi d'un faune to Pelléas" Archived 17 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Centre de documentation Claude Debussy, Bibliothèque nationale de France, retrieved 18 May 2018

Fulcher, Jane (2001). Debussy and his World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3195-1.

Jensen, Eric Frederick (2014). Debussy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973005-6.

Kennedy, Michael. "Impressionism", The Oxford Dictionary of Music, second edition, revised, Joyce Bourne, associate editor (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2006). ISBN 978-0-19-861459-3.

François Lesure and Roger Nichols, Debussy Letters (Harvard University Press, 1987): p. 188. ISBN 978-0-674-19429-8.

Ledbetter, Steven. Claude Debussy: La Mer, Three Symphonic Sketches. Boston Symphony Orchestra Program Notes. 2003-2004 Season. October 11, 2003. Pp. 39-43.

Lockspeiser, Edward (1978) [1962]. Debussy: His Life and Mind (Second ed.). Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22054-5.

McCallum, Stephanie. Decoding the Music Masterpieces: Debussy’s Clair de Lune. University of Sydney. July 26, 2017.

Newman, Ernest. "The Development of Debussy", The Musical Times, May 1918, pp. 119–203 (subscription required)

Nichols, Roger (1980). "Debussy, (Achille-)Claude". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-23111-1.

Orenstein, Arbie (1991) [1975]. Ravel: Man and Musician. Mineola, US: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-26633-6.

Phillips, C. Henry. "The Symbolists and Debussy", Music & Letters, July 1932, pp. 298–311 (subscription required).

Roberts, Paul (1996). Images: The Piano Music of Claude Debussy. Portland, Oregon.

"The Consecration" Archived 30 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Centre de documentation Claude Debussy, Bibliothèque nationale de France, retrieved 18 May 2018

Thompson, Oscar (1940). Debussy, Man and Artist. New York: Tudor Publishing. OCLC 636471036.

Tirebuck, Ben (11 August 2021). "World Sport: Tokyo 2020 Olympics emerges as a winner". The Phuket News Com. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

https://www.britannica.com/summary/Symbolism-literary-and-artistic-movement

Clair de Lune - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suite_bergamasque

Claude Debussy - Wikipedia

This is a wonderful piece about a phenomenal composer and one of his most iconic works . The guide to the many moving performances is icing on the cake 🍰 One of the coolest things about classical is the number of great performances a piece like Clair de lune provides the listener. Outstanding thanks for your writing !

Really like the Bavouzet and Cho suggestions. Thank you. I find Frederic Chiu's account to also be very satisfying. Similar to Bavouzet's in that it is a bit faster than average, yet still quite moving:

https://open.spotify.com/track/1rxcmWp7ujuP39u2P1Ehjm?si=86725c460584495e