Building a Collection #35: Brahms Ein Deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem)

With recommended recordings

Building a Collection #35

Ein Deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem), Op. 45

By Johannes Brahms

________________

Our next entry in our Building a Collection series seems particularly appropriate given the arrival of Easter. Johannes Brahms’ large choral work Ein Deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem) lands at #35 on the list, and I would suggest this is just the piece of the music we need at this moment in time. The full title of the work is Ein Deutsches Requiem, nach Worten der heiligen Schrift (A German Requiem, to Words of the Holy Scriptures). It is a sacred, but non-liturgical work, and so differs in this important respect from other requiems. Brahms’ Requiem is a touching work filled with words of mourning, but also comfort and compassion, and some of the most heart-stirring music ever created. But since Brahms was essentially a humanist, it avoids any overt mention of Christian dogma.

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms (b. 1833 – d. 1897) was a German composer of the Romantic era and is generally regarded as one of the greatest composers of all-time. Even though Brahms was from the Romantic era, he was very much connected to the Classical forms as seen in the works of Haydn, Mozart, and especially Beethoven. In that sense, Brahms represented a “conservative” approach to musical tradition at a time when form and convention were changing due to Wagner and others. Brahms wrote symphonies and other orchestral works, chamber music, concertos, keyboard works, vocal, and choral music.

Brahms was from a musical family in Hamburg and showed a great deal of promise even at a young age. He began as a pianist and would often perform around Hamburg in eating and drinking establishments. By adulthood, Brahms had become friends with well-known musicians of the time. He befriended the violinist Joseph Joachim, a relationship that would be personally and artistically important throughout his life. But perhaps most important was his friendship with the famous composer Robert Schumann. Schumann, twenty-two years older than Brahms, became his most fervent advocate. Brahms likewise had tremendous esteem for Schumann. Brahms practically became a member of Schumann’s family, and after Schumann’s death at the too young age of 46, Brahms continued to be close friends with his widow, the pianist and composer Clara Schumann. Brahms never married, although he apparently had several romantic relationships throughout his life. There is speculation about whether Brahms and Clara were more than friends, and there is evidence that Brahms was probably in love with her.

Many of his compositions have become universally known, and many are perennial favorites that are frequently programmed by orchestras around the world. As part of the “Big 3” of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, he occupies a central place in the history of classical music. His symphonies, choral works, concertos, and chamber music reflect his genius, and I urge you to listen to all his works. Three of my personal favorites are: Symphony no. 1 in C minor, Piano Trio no. 1 in B major, and our current subject Ein Deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem). Let’s delve deeper into Brahms’ Ein Deutsches Requiem.

Ein Deutsches Requiem

Ein Deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem), Op. 45 on words from Holy Scripture was composed by Brahms over an 11-year span, but most of it was completed between 1863 – 1867. An ambitious work for a young composer (Brahms was then in his early 30’s), it predates all of his symphonies. His Requiem would become his first great success, not just in Germany but worldwide. While Brahms was a Romantic composer, he also liked using more traditional models and forms hearkening back to Classical era and even Baroque era examples. Traditionally a Requiem is a liturgical setting from the Roman Catholic Mass, in music typically using the Latin liturgical text. However, Brahms’ Requiem is not liturgical in nature, and he does not use the standard Latin text, but rather chose his own texts from scripture and other texts. Also, he chooses to use the vernacular German rather than Latin.

While the focus of a traditional Requiem is on prayer for the dead, Brahms composed the work primarily to provide consolation for the living. It is neither a Mass nor an oratorio, and so in this sense it is a unique work. Although Brahms was raised as a North German Protestant, he was a skeptic and an agnostic when it came to religion. In this work, even the name of Christ is not used. Today we may call Brahms a secular humanist. Nevertheless, Brahms had an excellent knowledge of the scriptures, and thus he chose texts that reflect the universal human longing for comfort in the face of sorrow. The famous Czech composer Antonin Dvorak said of Brahms, “Such a great man! Such a great soul! And he believes in nothing!” Upon being told by a colleague that Jesus Christ himself, the central point of salvation, was not mentioned at all, Brahms himself would say: “I confess that I would gladly omit even the word ‘German’ and instead use ‘Human’. Also…I would dispense with places like John 3:16. On the other hand, I’ve chosen one thing or another because…I needed it, and because with my venerable authors I can’t delete or dispute anything.” It is notable that Brahms titles the work with “Ein” or “A” German requiem, rather than “the” requiem, perhaps reflecting his admission that this is his own singular take on death and redemption.

There is evidence Brahms found inspiration to compose a Requiem after suffering two personal losses of his own. His beloved mother died in 1865, and his dear friend the composer Robert Schumann died in 1856. Shortly after proclaiming Brahms the next German musical genius, Schumann attempted suicide by plunging into the Rhine River. At Schumann’s own request, he was admitted to a mental asylum and died two years later still suffering from mental illness. Within days of Schumann’s suicide attempt, Brahms had sketched what would become the second movement of his Requiem: “For all flesh is as grass”.

Ein Deutsches Requiem in its final completed form with seven parts was first performed in 1869 at the inaugural concert for the opening of the Leipzig Gewandhaus concert hall. The seven parts are as follows:

1. Selig sind, die da Leid tragen (Blessed are they that mourn)

2. Denn alles Fleisch es ist wie Gras (For all flesh is as grass)

3. Herr, lehre doch mich (Lord, make me to know)

4. Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen (How amiable are thy tabernacles)

5. Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit (Ye now have sorrow)

6. Denn wir haben hie keine bleibende Statt (For here we have no continuing city)

7. Selig sind die Toten (Blessed are the dead)

Much of the work has a tone of consolation and mercy. There are important contributions from two soloists, a soprano and a baritone. Their solo parts are tremendously important to a successful performance, as well as the parts for a highly trained chorus.

The first two movements are choral, and emphasize the mourning and sorrow of death, but also of rejoicing and comfort in the end. The second movement is particularly haunting, very much beginning in a dark mood. I recall the History Channel using the beginning of this movement as background theme music for a series on the Nazis years ago. That was an unfortunate use of the music, as the movement again eventually returns to a joyful and hopeful place. The baritone solo is heard in the third movement, expressing desolation at the human condition, but the movement again ends in joy and hope, “But the souls of the righteous are in the hands of God.”

The soprano solo is in the fifth movement, again with words of hope: “Ye now have sorrow: but I will see you again, and your heart shall rejoice…” and “I will comfort you as one whom his mother comforteth.”

The sixth movement is particularly powerful in its structure and power. The music here, for me, is among the most brilliant music Brahms ever composed. At once using both new melodies and yet old forms, Brahms is attempting to express eternal truths. Brahms pays homage here to Handel in his writing a fugue in the second part of the movement, and even uses some of the same text as Handel: “Thou art worthy, O Lord, to receive glory and honor and power; for thou hast created all things, and for thy pleasure they are and were created.” Of course this echoes Handel’s Messiah, and the fugue is a baroque feature that Brahms incorporates. The power of this movement is such that, at the end with the use of the kettle drums and a big climax, it feels like the end of the work. Indeed, you would be forgiven for standing and applauding at this point. But no, there is another movement, and the final movement is again full of comfort and sympathy for the dead and the living alike.

The complete text in German, with English translation, can be found here:

https://web.stanford.edu/group/SymCh/supplements/brahms-requiem-text.html

Essential Recording

I have listened again to all the major recordings of Ein Deutsches Requiem, and I have reassessed both the work itself and what is important in a recording. In fact, I have decided to replace the Ein Deutsches Requiem recording in my Top 50 Classical Recordings of All-Time with the essential recording listed below. I have also added and removed a few of the recordings I recommended previously.

German conductor Otto Klemperer (1885 - 1973) was one of the great Brahms conductors of the 20th century, and his 1961 EMI/Warner recording with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Chorus with soloists soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau has stood the test of time and fully deserves to be called an “essential” recording of this great work. Although it was recommended in my earlier series, it will now also take its rightful place in the Top 50 recordings of all-time. Klemperer’s way with Brahms is direct, clear-eyed, and almost stoic as he gets to the emotional core without over-sentimentalizing. In addition, he has two of the finest soloists to ever record the work in Schwarzkopf and Fischer-Dieskau. Fischer-Dieskau is particularly moving, caught rather earlier in his career before he began shouting at notes. The Philharmonia was certainly one of the finest orchestras in the world at the time, and the chorus is firm and clear. Recorded at Kingsway Hall in London the sound is not perfect but remasterings have improved things over the years and it is more than acceptable. In terms of tempos and dynamics, Klemperer treads a middle ground, but at times he can be significantly quicker than was the norm in his day which is an asset. I can’t get enough of the horns in the second movement Denn alles Fleisch in the buildup to the climax (both times), it sends chills. EMI labeled this recording one of their “Great Recordings of the Century”, and I completely agree.

Other Recommended Recordings

Despite the constricted quality, I enjoy Herbert von Karajan’s (1908 - 1989) first recording in mono from 1947 on EMI/Warner with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and Vienna Singverein with the outstanding soloists soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and baritone Hans Hotter. In terms of the performance, it is the best of Karajan’s recordings of Brahms Requiem, made before he became obsessed with surface beauty in recordings. It still reflects typical performance practice of the time with slower tempos and thicker textures, but these qualities also bring special insights and enjoyment.

German conductor Rudolf Kempe (1910 - 1976) did not always rise to greatness on record, but his 1955 EMI/Warner recording of Ein Deutsches Requiem with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and the Chorus of St. Hedwigs-Kathedrale does indeed rise to such a level. Once again, we have a young Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau singing superbly in his two movements, and Elisabeth Grümmer floats a bright and shimmering tone in the fifth movement. The St. Hedwigs chorus performs admirably, especially in the first, second, and fourth movements. The performance has a reverential feeling to it, Kempe is not in any rush but allows things to unfold naturally. The acoustic of the Jesus-Christ-Kirche in Berlin has long been favored for its warmth and radiance. The recording shows its age, though it is noticeably better than the Karajan recording above. Recommended.

The 1984 recording on the Orfeo record label featuring the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Wolfgang Sawallisch (1923 - 2013) is powerful and moving. The soloists are soprano Margaret Price and baritone Thomas Allen. It was recorded in the legendary acoustic of the Herkulessaal concert hall in Munich. As mentioned above, having quality soloists is essential to this work, and what really raises this recording to recommended status is the singing of the two soloists. Before hearing this recording, I already greatly admired the voices of Margaret Price and Thomas Allen individually from the opera world but having them together on this recording in their prime is great fortune. Both singers combine beauty of tone with power and confidence. They truly understand the text, the mood and the dynamics of the piece. Thomas Allen is particularly moving throughout. The Bavarian Radio Chorus is equally impressive, clear and weighty. The energy of the chorus, and their obvious devotion to the piece, also gives credit to Sawallisch’s overall conception of the work. There is gentleness and comfort where needed, but also power and joy in climaxes. One small warning, because this recording is an early digital recording, there is some “digital congestion” that creates some added sheen and distortion at loud volumes with some listening equipment. It has a wide dynamic range, and while I enjoy the clarity of the recording, I found myself turning down the volume during loud passages.

I recommend the 1988 recording on the Deutsche Grammophon label by Carlo Maria Giulini (1914 - 2005) and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and the Vienna State Opera Chorus with the incomparable American soprano Barbara Bonney and baritone Andreas Schmidt. Taken slower, this recording emphasizes a more devotional and reflective mood. But in the hands of the master Giulini, it brings out all the emotion and heartfelt joy in the piece. This is almost the opposite sort of approach to the Gardiner recordings (below), but no less valid as an interpretation. Giulini’s recordings of the Brahms’ symphonies with the VPO around the same time are simply TOO slow, but thankfully here he holds everything together. The sound from the Musikverein in Vienna is not ideal, the chorus is too recessed and to me even the orchestra is too recessed as well, meaning they are too far back in the sound picture to properly hear all the details. You can still feel the power and magnetism of the reading, but it also tends toward congestion in climaxes. Thankfully this does not overshadow the effectiveness of the performance, especially since both Barbara Bonney and Andreas Schmidt are among the finest on record. Schmidt rivals Fischer-Dieskau and Hotter in this performance (he also sings quite well on Abbado’s recording, not listed here), and I would actually pick Schmidt over anyone else. His rich, sonorous baritone has heft and emotion, and the notes are easy for him to reach. Bonney, one of my all-time favorite voices in classical music, brings her pure and clear tone along with a disarming innocence and characterization of the text. So if you are in the mood for a traditional reading with power and reverence, paired with excellent soloists, this is a good choice.

Both recordings by Sir John Eliot Gardiner with the Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique and Monteverdi Choir are highly recommendable (the first recording on Philips from 1991, and the second recording from 2012 on their own Soli Deo Gloria label). Soloists on the 1991 account are soprano Charlotte Margiono and baritone Rodney Gilfry, while the 2012 recording features soprano Katharine Fuge and baritone Matthew Brook. Both recordings use period instruments and are similar, but the more recent one has the advantage of even better sound and clarity. On the other hand, I somewhat prefer the soloists from the first recording. But overall the performances are quite similar and both are recommended. What Gardiner achieved with Ein Deutsches Requiem is admirable, essentially creating more transparency in the choral and orchestral textures while moving the tempi forward marginally faster. There are other period instruments and historically-informed practice recordings, but Gardiner just does it better than anyone else. His Monteverdi Choir is exceptional, and the orchestra is equally splendid. Brahms even expressed his preference for smaller choral and orchestral forces for the work, and it is easy to understand why with performances as fine as both of these recordings. I like how Gardiner doesn’t obsess about the beauty of the sound produced but rather remains true to the original instrument and playing styles as they may have been heard in the day. I would still label myself a period instrument and HIP skeptic when it comes to Brahms, but Gardiner convinces me in this work (though I would still skip Gardiner’s take on the Brahms’ symphonies). Both recordings are recommended.

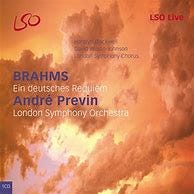

German-American conductor André Previn’s (1929 - 2019) 2000 live recording with the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus on the LSO Live label is a real gem, with soloists soprano Harolyn Blackwell and baritone David Wilson-Johnson. Previn’s approach is somewhat leaner and quicker than most traditional accounts, and he focuses on the rhythmic vitality and the choral excitement. Even though it was recorded at the Barbican in London, a notoriously difficult recording venue, the level of detail and clarity from the LSO chorus is astounding. We hear the softer and louder choral passages equally well, their German is precise, and they also handle the more fugue of the sixth movement extremely well. The horns, trumpets, and timpani are also captured superbly. Wilson-Johnson is above average (though he doesn’t rival Fischer-Dieskau, Hotter, or Schmidt), and once I became accustomed to Blackwell’s somewhat unique vibrato I found her voice quite appropriate for the piece. I saw Previn conduct live several times in his final few years, and it always seemed like he was on autopilot, leading performances which were rather flaccid and uninspiring. Thus, I was very happy to find this recording which shows Previn as the great conductor he surely was, especially when leading the LSO, the band he made his best recordings with over the years.

Other Recordings of Note

I am not the final word on recordings of Ein Deutsches Requiem, and so of course there are many other fine recordings you may want to check out listed below. I like all the recordings below as well, though one flaw or another keeps each of them from my recommended list. The recordings below are listed in chronological order by recording date:

Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir / Wilhelm Furtwängler (Warner, 1948)

New York Philharmonic & Westminster Choir / Bruno Walter (Sony, 1954)

Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus / Rafael Kubelik (Audite, 1978)

Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus / James Levine (RCA/Sony, 1984)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and Vienna Singverein / Herbert von Karajan (DG, 1985)

London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus / Richard Hickox (Chandos, 1990)

San Francisco Symphony Orchestra and Chorus / Herbert Blomstedt (Decca, 1993)

Orchestre Des Champs-Elysees & Collegium Vocale / Philippe Herreweghe (Harmonia Mundi, 2002)

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra & Rundfunkchor Berlin / Sir Simon Rattle (Warner, 2006)

Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra & Swedish Radio Choir / Daniel Harding (Harmonia Mundi, 2018)

Brahms’ Requiem is among my favorite pieces of music ever composed, and I have also been fortunate enough to see it performed live on three occasions (twice by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the Tanglewood Chorus, led by Bramwell Tovey and Andris Nelsons respectively, and once by the Colorado Symphony Orchestra and Chorus led by Peter Oundjian. The Tovey performance was unforgettable, the Nelsons performance was disappointing and the Oundjian performance was moving). The tremendous impact and importance of this work cannot be overstated in my opinion. Happy listening!

Join me next time when we will discuss #36 on our list, Claude Debussy’s Clair de Lune. See you then.

_________________

Notes:

Brennan, Gerald. Schrott, Allen. Woodstra, Chris. All Music Guide to Classical Music, The Definitive Guide. All Media Guide. Pp. 188, 203. Backbeat Books, San Francisco. 2005.

Schonberg, Harold C. The Lives of the Great Composers (Revised Edition). Pp. 305. W. W. Norton & Company, New York. 1981.

Swafford, Jan (2016). Johannes Brahms: Ein Deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem), Op. 45, on words from Holy Scripture. Boston Symphony Orchestra Program Notes, Week 2, 2016-2017 Season. Pp. 39-47.