Building a Collection #34: Mozart's Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro)

With recommended recordings

Building a Collection #34

Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro)

By Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

__________________________________________________________

Number 34 on the Building a Collection survey is Mozart’s opera Le Nozze di Figaro. It is the fifth opera on our list, and the third opera by Mozart (the first two being The Magic Flute and Don Giovanni). Le Nozze di Figaro (1786) is in four acts with a libretto by the Venetian Lorenzo Da Ponte, the same librettist Mozart worked with for Don Giovanni (1787) and Cosi Fan Tutte (1790). The opera is considered an “opera buffa” or a musical comedy and is based on the 1784 stage play La folle journée, ou le Mariage de Figaro ("The Mad Day, or The Marriage of Figaro") by the French multi-talented artist Pierre Beaumarchais.

The opera premiered at the Burgtheater in Vienna on May 1, 1786, and is widely regarded to be one of the greatest operas of all time. Even though The Magic Flute and Don Giovanni rank higher on our list, you can really take your pick between them because they are all works of undeniable genius and lasting enjoyment.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

The information below on Mozart has been included in the two previous posts on this list, so if you have read those posts you can safely jump down to the information specific to Le Nozze di Figaro.

The incomparable genius Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (b. 1756 – d. 1791) was an Austrian composer of opera, symphonic works, concertos, choral and vocal works, keyboard pieces, orchestral works, and chamber music. Despite his short life, Mozart produced more than 800 works, and scholars say he likely composed even more that will never be known or recovered. Mozart was the only son of a proud, infamous, and rather exploitative father by the name of Leopold Mozart. When Leopold realized his son’s prodigious talent on the keyboard, he toured him all around Europe to show him off. It is debated whether these trips contributed to Mozart’s chronic illnesses, as he had bouts of typhus and smallpox during childhood. In any case, it left Mozart with a lot of resentment for his father. Indeed, Mozart would later boycott his own father’s funeral.

Although Mozart was employed off and on by royalty beginning in 1782, he was essentially self-employed. He married Constanze Weber in 1783 without his father’s approval. Astonishingly, by the age of 20 Mozart had written nine operas, five violin concertos, at least 30 symphonies, sets of divertimentos and serenades, many liturgical works, six sonatas, and six concertos for piano. Although Mozart had several teachers, including his father, he was increasingly influenced by Michael Haydn (younger brother of legendary composer Franz Josef Haydn). Between the years 1782 and 1786, Mozart produced a group of piano concertos from no. 12 to no. 25. He would go on to write only two more piano concertos before his death. His final five operas are generally considered his greatest: Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro), Don Giovanni, Cosi Fan Tutte (All Women Act That Way), Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), and La Clemenza di Tito (The Clemency of Titus). His symphonic production reached its apex with his final four symphonies, nos. 38 – 41.

Mozart’s music remains one of the archetypes of the classical style, and it is known for its intricacy, melodic inventiveness, harmony, and rich textures. Mozart advanced music in ways that were unique and rather bewildering to his contemporaries, and he especially developed the use of counterpoint well beyond where it had been during the late baroque period.

If you would like to read more about Mozart, there are some wonderful biographies including:

Keefe, Simon P (2018). Mozart. Routledge.

Solomon, Maynard (1995). Mozart: A Life. Harper Collins.

Suchet, John (2017). Mozart: The Man Revealed. Pegasus.

Swafford, Jan (2020). Mozart – The Reign of Love. New York: Harper.

Till, Nicholas (1995). Mozart and the Enlightenment: Truth, Virtue and Beauty in Mozart's Operas. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company.

Le Nozze di Figaro

Beaumarchais had previously written a play called The Barber of Seville, and although today we know the opera by Rossini by that name, it was first made into an opera by Giovanni Paisiello. However, Beaumarchais’ Marriage of Figaro play was found to be objectionable by Emperor Joseph II and the Austrian Censor, presumably for its sexual references and descriptions of class struggle. However, after Da Ponte’s treatment of the text he was able to obtain official approval for the operatic version. Mozart was the one that selected the play and brought it to Da Ponte for the project. All political references and the more obvious sexual references were removed, and thus approval was given even before Mozart had written any music. Mozart was paid some 450 florins for the work, several times more than his previous annual salary as a court musician.

While some of the first performances in Vienna were received cordially, if not enthusiastically, it was still generally considered a success. Once the opera moved to Prague later, it received both critical and public praise and was accepted as a tremendous success.

The newspaper Wiener Realzeitung carried a review of the opera in its issue of 11 July 1786. It alludes to interference probably produced by paid hecklers, but praises the work warmly:

“Mozart's music was generally admired by connoisseurs already at the first performance, if I except only those whose self-love and conceit will not allow them to find merit in anything not written by themselves.

The public, however ... did not really know on the first day where it stood. It heard many a bravo from unbiased connoisseurs, but obstreperous louts in the uppermost storey exerted their hired lungs with all their might to deafen singers and audience alike with their St! and Pst; and consequently, opinions were divided at the end of the piece.

Apart from that, it is true that the first performance was none of the best, owing to the difficulties of the composition. But now, after several performances, one would be subscribing either to the cabal or to tastelessness if one were to maintain that Herr Mozart's music is anything but a masterpiece of art. It contains so many beauties, and such a wealth of ideas, as can be drawn only from the source of innate genius.”

The primary characters in Le Nozze di Figaro are as follows:

Figaro (bass-baritone) - The same Figaro as in The Barber of Seville, but now a few years older. He is clever and enterprising, and the personal valet to the Count.

Susanna (soprano) - Susanna is brave and resourceful, she uses her charm and wit to fend off the advances of the Count (her employer) and remains faithful to her fiancé Figaro. She is the Countess’ maid.

Count Almamiva (baritone) - The Count is arrogant, creepy, and entitled. He is Lord of the Aguas-Frescas estate, near Seville, where Le Nozze di Figaro takes place. His wife the Countess Almamiva is the same Rosina from The Barber of Seville. He is now bored with married life, and preys on younger, subservient women.

Countess Almamiva (soprano) - Faithful, brave, and kind-hearted, the Countess is depressed about her husband’s infidelity. She enlists the help of her servant Susanna to help her.

Cherubino (mezzo-soprano/soprano) - Charming, passionate, and fearless, Cherubino is the Count’s page. Cherubino is what is known as a “trouser role” in opera, a woman playing an adolescent boy with an unbroken voice. Although in love with the Countess, he flirts with the other females in the opera as well.

Synopsis

The Glyndebourne Opera online provides a synopsis of the opera:

Act I

Susanna tries on a wedding bonnet, whilst her fiancé Figaro measures the room in the castle given to them by the Count. She points out its dangerous proximity to the Count, reminding Figaro of the droit de seigneur, the ancient feudal right of masters to dally with their maiden servants. Figaro vows to thwart him.

Figaro’s old enemy Bartolo and Bartolo’s former servant Marcellina enter with a marriage contract between Marcellina and Figaro, which they intend to enforce.

The page Cherubino enters, protesting about being sent away to the army because the Count found him dallying with the gardener’s daughter Barbarina. When the Count approaches, he hides.

The Count romances Susanna. Her singing teacher Basilio arrives, forcing the Count to hide. When the Count comes out of hiding, he discovers the hidden Cherubino.

Figaro arrives with a group of peasants praising the Count for abolishing the droit de seigneur. The Count sends Cherubino off to join his regiment.

Act II

The Countess laments her husband’s neglect. Susanna tells her of his designs on her, and of Figaro’s plan to send a cross-dressed Cherubino to meet the Count instead of her. Cherubino arrives to prepare for his ‘tryst’ with the Count, but the Count’s arrival forces him to hide in the closet. Susanna returns unobserved and hides.

The Count, told that Susanna is hiding in the closet, demands that she emerge. He goes to fetch tools to open the door, taking the Countess with him. Susanna releases Cherubino, who escapes through the window while she enters the closet. Returning with her husband, the Countess confesses that Cherubino is inside. Both are nonplussed when Susanna emerges.

Figaro arrives. The gardener Antonio enters complaining about someone jumping from the window; Figaro claims it was him. The Count is relieved when Bartolo, Marcellina and Basilio enter, demanding that Figaro marry Marcellina or repay his debt.

Act III

The Count pursues Susanna. She agrees to a rendezvous, but the Count then overhears her plotting with Figaro.

Alone, the Countess ponders her unhappy marriage. Meanwhile, Marcellina has won the court case on her marriage contract. Figaro confesses that he was born into a respectable family and requires his parents’ consent. In his description of his history, Marcellina recognises Figaro as her long- lost son; Bartolo is his father.

Susanna and the Countess write to the Count inviting him to the rendezvous; a pin must be returned as acknowledgement. A group of peasant girls arrives offering flowers to the Countess, with the disguised Cherubino among them. Barbarina forces the Count to agree to let her marry Cherubino. The wedding celebrations begin. Susanna passes the letter to the Count.

Act IV

That night in the garden, Barbarina laments losing the pin she was to return to Susanna. Figaro resolves to interrupt the tryst between Susanna and the Count. Marcellina goes to forewarn Susanna. Barbarina, Figaro, Bartolo and Basilio hide. Disguised in each other’s clothes, Susanna and the Countess enter to ensnare the Count.

Cherubino arrives seeking Barbarina, but sees (as he thinks) Susanna, and flirts with her. The Count takes Cherubino’s place wooing ‘Susanna’. Figaro, seeing through Susanna’s disguise, feigns seducing ‘the Countess’, and is caught by the Count, who refuses to forgive his wife for her apparent infidelity. The truth is revealed, and all is set right.

The Overture alone is one of the most well-known pieces of music by Mozart and is often performed alone in many concerts.

Le Nozze di Figaro has some of the most famous tunes in classical music, and contains some of the most recognizable arias in opera including:

“Se Vuol Ballare” (Act I) - Figaro

“La Vendetta” (Act I) - Bartolo

“Non so più” (Act I) - Cherubino

“Non più andrai” (Act I) - Figaro

“Porgi amor” (Act II) - Countess

“Voi che sapete” (Act II) - Cherubino

“Venite inginocchiatevi” (Act II) - Susanna

“Hai già vinta la causa” (Act III) - Count

“E Susanna non vien – Dove sono i bei momenti” (Act III) - Countess

“Giunse alfin il momento – Deh vieni non tardar” (Act IV) - Susanna

“Pian pianin le andrò più presso” (Act IV) - Ensemble

Harold Schonberg in The Lives of the Great Composers writes of Le Nozze di Figaro:

“Le Nozze di Figaro opens the door to a new world of opera. It is a scintillating work with real people in it, and the music exposes them for what they are — lovable, vain, capricious, selfish, ambitious, forgiving, philandering. Human beings, in short, all brought alive by the alchemy of a surpassingly inventive and sympathetic musical mind. In Figaro there is not one flawed note, not one situation that rings false.”

In 2017, BBC Music Magazine described Le Nozze di Figaro as "one of the supreme masterpieces of operatic comedy, whose rich sense of humanity shines out of Mozart’s miraculous score".

A note on recordings

When approaching recordings of Le Nozze di Figaro, it is important to know it is a relatively long opera in four acts where the conductor and orchestra play an essential role, and where the correct casting of voices is absolutely essential. Even under studio conditions, it is difficult to get it all “right” from conductor to orchestra to singing quality to acting ability. It is easy to let the tension slack, or for one (or more) of the cast to disappoint. There is also the question of whether a performance is “complete” with all recitatives and sometimes omitted numbers included. I won’t really get into that in my recommendations, as I have focused more on the traditional musical numbers. I am also skipping any recordings using German language, as I far prefer the original Italian. But if you are interested, the 1964 recording by Otmar Suitner in German is quite good.

The other thing, especially with opera, is whether there are any recommended DVDs of live performances. On this point I have to defer to other reviewers, as I am not as familiar with DVD productions of Le Nozze di Figaro.

Essential Recording

Although there were a few very good recordings of Le Nozze di Figaro before it, including Fritz Busch’s historical 1934-35 mono recording from the Glyndebourne Festival, and Karajan’s first recording from 1950, for me no recording surpasses Erich Kleiber’s sparkling account from 1955 on Decca with the Vienna Philharmonic and the Vienna Staatsoper Chorus. Kleiber’s conducting is exactly right at every turn and the VPO is with him all the way and they produce an exquisite sound. Cesare Siepi is ideal as Figaro, Hilde Gueden is marvelously innocent yet playful and vocally assured as Susanna, Lisa Della Casa is pure-voiced and vulnerable as the Countess, and Suzanne Danco as Cherubino is an absolute pleasure despite her voice being rather unconvincing for a trouser role. Recorded in the Redoutensaal in Vienna in early stereo, the sound is fine but you must make some allowances for its age. More than anything else, the performance holds together musically and dramatically from beginning to end, a significant feat. It is a delightful performance, and one to treasure.

Recommended Recordings

In chronological order by recording date:

Modern music specialist and very underrated Austrian conductor Hans Rosbaud was also an accomplished Mozart conductor, and he led a marvelous live performance in mono sound with the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire (Paris) from the 1955 Aix-en-Provence Festival in France (has been on the Walhall label and the Stradivari label). Soloists are Rolando Panerai as Figaro, Rita Streich as Susanna, Heinz Rehfuss as Count Almamiva, Teresa Stich-Randall as the Countess, and Pilar Lorengar as Cherubino. If you can tolerate the somewhat brittle mono sound, with the common issues of a live performance, this is a truly great performance. Panerai is wonderful as Figaro with his deep, round voice, his impeccable Italian diction, and his solid characterization. Streich is terrific as Susanna, surely one of the best on record with a clean and pure tone. Stitch-Randall is completely assured as the Countess, playing the role with emotion and vulnerability. Cherubino is a young Pilar Lorengar, and her voice is near ideal for the role, convincing in its boyishness without becoming too deep. The singers in the smaller roles are all average or better. Rosbaud chooses his tempos well, and the orchestra is precise and engaged throughout. A top-notch choice if the sound doesn't deter you.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Austrian conductor Erich Leinsdorf was on a roll of sorts, leading several excellent recordings including Don Giovanni, Die Walküre, and this very fine Le Nozze di Figaro. Recorded by Decca in stereo in 1958 with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, it includes soloists Giorgio Tozzi as Figaro, Roberta Peters as Susanna, George London as Count Almamiva, Lisa Della Casa as the Countess, and Rosalind Elias as Cherubino. Although unavailable in many places for years, this recording is now on streaming services (on the Urania label). It should never be out of circulation, as it is one of the finest recordings of this opera. Leinsdorf is inspired here, leading a performance that is sharply defined with an appealing forward momentum. The Vienna strings sound rich and glowing, and the sound overall is worthy of Decca’s finest from the era. Tozzi is fully in character, as is Peters, and their numbers together are a joy to hear. Peters is delightfully pointed and bubbly, while Tozzi is able to vary his darker voice quite naturally as needed for Mozart. Similar to Lorengar above, Elias fits the role of Cherubino quite nicely with her boyish and passionate characterization. London, a celebrated Wagner singer, similar to Tozzi is able to lighten his tone for the role of Count. Della Casa is simply one of my favorite voices in all opera and here she is every bit as convincing as any Countess on record. Recommended.

Italian conductor Carlo Maria Giulini also made several landmark recordings in the late 1950s and early 1960s with the Philharmonia Orchestra (London), including this excellent Nozze dating from 1959 on EMI/Warner. The soloists are Giuseppe Taddei as Figaro, the splendid Anna Moffo as Susanna, Eberhard Wächter as Count Almamiva, the incomparable Elisabeth Schwarzkopf as the Countess, and a young Fiorenza Cossotto as Cherubino. The sound is clear and immediate, and the overture virtually comes bursting out of the speakers. While I am not fond of Taddei’s tendency to bark and snarl, he certainly gives the role of Figaro character and his singing is quite good. The precision of the cast’s Italian is ideal, and Giulini’s direction has vision and propulsion. Moffo’s Susanna reminds me of her iconic role as Musetta in La Boheme (on several recordings, most notably with Maria Callas from 1956), and how much I have always liked her voice. Cossotto is early in her career, and at that point she could use a wide range of tones and colors and was effective in portraying Cherubino. Eberhard Wächter’s Count is also very good, at this point in his career he could produce either a menacing or a genial character. Schwarzkopf is just ideal as the Countess, one of her signature roles, and as usual is one of the strengths of the cast. This is a very enjoyable recording, and warmly recommended.

Long-time Swiss opera conductor Silvio Varviso was a regular at the Metropolitan in New York, and he led a superb live performance of Le Nozze di Figaro at the Glyndebourne Festival in 1962, preserved in surprisingly good sound. I had to find it on YouTube, but it is also available on CD (on Glyndebourne’s own label) for a price. Along with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Glyndebourne Chorus, the cast includes Heinz Blankenburg as Figaro, Mirella Freni as Susanna, Gabriel Bacquier as Count Almamiva, Leyla Gencer as the Countess, and Edith Mathis as Cherubino. Varviso seems to have an intuitive sense of Mozart’s flow and how the music should accompany each character. Blankenburg was unknown to me, but he makes a very fine Figaro. I especially enjoy him in Acts I and IV. Freni is her usual reliable Susanna, in better voice than 1974 for Karajan (see below). Leyla Gencer has a rather heavy and florid voice, not altogether ideal for the Countess, but she knows how to use her powerful instrument. Bacquier is eloquent and incisive in his singing, and Mathis is a lovely, if a bit too feminine Cherubino. The audience is clearly enjoying the performance, as you can hear laughter on several occasions. Very enjoyable.

Sir Colin Davis’ 1971 set for Philips/Universal made with BBC Symphony Orchestra has much to recommend it, with soloists Wladimiro Ganzarolli as Figaro, Mirella Freni as Susanna, Ingvar Wixell as Count Almamiva, the great Jessye Norman as the Countess, and Yvonne Minton as Cherubino. The first real star of this recording is Colin Davis because his conducting is perceptive, energetic, and completely committed. The BBC orchestra plays their heart out for him, they are incisive, precise, and sound great. Freni is at the top of her game as Susanna, and Wixell is captivating as the Count (you should hear his “Hai già vinta la causa”) reminding me of what an excellent Baron Scarpia he was on Davis’ Tosca from around the same time. Minton is a superb Cherubino, singing with warmth and clarity. Jessye Norman’s voice is altogether too large for Mozart, but she knows how to manage it here and strikes just the right tone for the Countess. Her “Dove sono” is nothing short of thrilling. The only reservation for me is Figaro himself, sung by Ganzarolli. I would not put him at the top tier of Figaros on record, though he doesn’t ruin the set for me. The rest of the recording is so outstanding, having an average Figaro is okay on this occasion. The concluding ensemble number is just terrific. Definitely one to keep.

Herbert von Karajan conducted two live performances of Nozze at the Salzburg Festival, one in 1974 and another in 1977. The live recording from 1974 with the Vienna Philharmonic and Vienna Staatsoper is the best performance, although I had to resort to YouTube to find it. The cast is outstanding including José van Dam as Figaro, Mirella Freni as Susanna, Tom Krause as Count Almamiva, Elizabeth Harwood as the Countess, and Federica Von Stade as Cherubino. Karajan likes pushing the action forward in this opera, and he does so here as well. The sound is not as good as the live Varviso recording despite being recorded more recently. Harwood is lovely as the Countess, and even though Freni is not as fresh-voiced as in the Varviso set, she was an excellent Susanna. Van Dam is one of my favorite Figaros on record, completely convincing in the role, and his voice up to any challenge up and down the scale. Tom Krause was not a natural Count, as he made his name in Wagner, but he is certainly powerful. Of course Von Stade is the ideal Cherubino once again, boyish yet also sensitive. Karajan’s 1950 recording on EMI is also worth hearing, although the sound is not ideal and there are no recitatives so you need to know the story.

The 1981 Decca digital recording with Sir Georg Solti leading the London Philharmonic Orchestra remains a personal favorite and probably a close second to Kleiber. Combining Solti’s drive and elan with what I believe to be perhaps the best singing of any opera recording ever makes this a winner. The cast includes Samuel Ramey as Figaro, Lucia Popp as Susanna, Thomas Allen as Count Almamiva, Kiri Te Kanawa as the Countess, and Federica Von Stade as Cherubino (and it should be mentioned the legendary bass Kurt Moll as Bartolo). Together they form what I view as the strongest cast ever for a Le Nozze di Figaro recording. Solti can be hard-driven at times, and critics say the performance misses something of the charm and comedy of the work. Ultimately this is why it is not in my “essential” category. However, the recording gets so much right it deserves to be in every Mozart lover’s collection. Samuel Ramey is firm and strong as Figaro, and Thomas Allen is simply the finest Count on record with a distinctiveness and even a menacing edge to his voice. Lucia Popp in my view is the greatest Susanna ever, and Kiri Te Kanawa is caught in her prime with a golden, creamy voice as the Countess. Te Kanawa’s performances of both “Porgi amor” and “Dove sono” are meltingly beautiful and worth the cost of the entire set. Did I forget Cherubino? Federica Von Stade is THE Cherubino of the century, she owned the role in the 1970s and 1980s and she brings her best here (even though her Italian is not exactly perfect). Solti’s direction is purposeful, but not unfeeling. All told, this recording is a wonder to hear and is absolutely recommended.

I have always felt Mozart was Sir Neville Marriner’s best composer to conduct, whether his very good accounts of the symphonies or the piano concertos with Alfred Brendel. His 1985 digital recording of Nozze for Philips with his own Academy of Saint-Martin-in-the-Fields is quite good, with soloists José van Dam as Figaro, Barbara Hendricks as Susanna, Ruggero Raimondi as Count Almamiva, Lucia Popp as the Countess, and Agnes Baltsa as Cherubino. Marriner’s orchestra is somewhat smaller than others on this list, which brings benefits such as clearer instrumental transparency and pointed rhythms (the band is glorious on the march at the end of “Non più andrai”) . Van Dam takes an essentially dark approach to Figaro, and uses his rich baritone to convey annoyance and even anger. Hendricks was in her prime at the time, and she sounds lovely as Susanna, both poised and sweet. Lucia Popp takes the part of the Countess here, and while she is more successful as Susanna on Solti’s set, she is still a formidable Countess with her powerful and lyrically expressive voice. I have never particularly cared for Raimondi’s voice, but he is successful here in projecting the smooth and persuasive Count. Baltsa brings her smoky and impassioned mezzo to Cherubino, a real delight, even if Marriner pushes the tempo on “Non so più” too hard. Robert Lloyd as Bartolo is a bonus too. This is a recording with a great deal of personality and voices of distinction. Recommended.

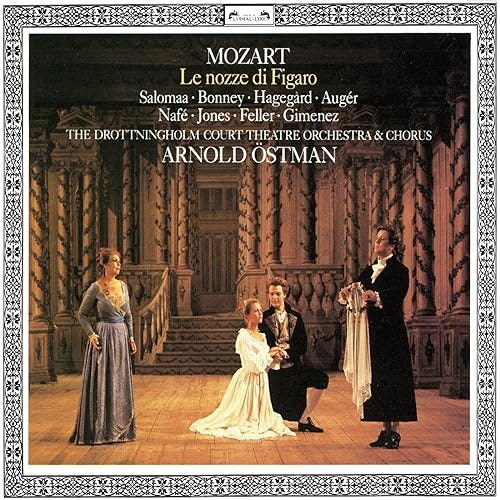

The only period instrument recording on the recommended list is by Drottningholm Court Theatre Chorus & Orchestra led by conductor Arnold Östman. Recorded in 1987 by the L'oiseau Lyre label (Decca), it includes a cast of Petteri Salomaa as Figaro, Barbara Bonney as Susanna, Håkan Hagegård as the Count, Arleen Augér as the Countess, and Alicia Nafé as Cherubino. This Nozze contains vitality and energy, although with lighter orchestral textures. Salomaa and Bonney are terrific together, and Bonney is one of my favorite voices in opera. Salomaa is clear, with a pleasant voice. Speeds are generally faster, but never extremely so. Augér conveys emotion and vulnerability in her Countess, and Hagegård is more than serviceable. Alicia Nafé’s Cherubino is not particularly memorable, but again doesn’t detract. There is life and joy in this reading, and Östman is more flexible in his direction than Gardiner (see below).

Other Recordings of Note

The recordings below for one reason or another don’t make my recommended list, but each has some good to great qualities which you may enjoy more than I do. They are listed in chronological order by recording date:

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Herbert von Karajan (1950, EMI/Warner)

Glyndebourne Festival Orchestra / Vittorio Gui (1955, EMI/Warner)

Deutsche Oper Berlin / Karl Böhm (1967, DG)

New Philharmonia Orchestra / Otto Klemperer (1970, EMI/Warner)

English Baroque Soloists / Sir John Eliot Gardiner (1993, Archiv/Decca)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Claudio Abbado (1994, DG)

Chamber Orchestra of Europe / Yannick Nézet-Séguin (2016, DG)

We made it to the conclusion of another great classical work, so thank you once again for reading and for your support. Next time we will be covering Johannes Brahms’ great choral work Ein Deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem). See you then!

________________

Notes:

Brockett, Oscar G. and Franklin J. Hildy. 2003. History of the Theatre. Ninth edition, International edition. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-41050-2.

Broder, Nathan (1951). "Essay on the Story of the Opera". The Marriage of Figaro: Le Nozze di Figaro. By Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus; Da Ponte, Lorenzo (piano reduction vocal score). Translated by Martin, Ruth; Martin, Thomas. New York: Schirmer. pp. v–vi. (Quoting Memoirs of Lorenzo da Ponte, transl. and ed. by L. A. Sheppard, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1929, pp. 129ff.

Deutsch, Otto Erich (1965). Mozart: A Documentary Biography. Stanford University Press.

Eisen, Cliff; Sadie, Stanley (2001). "Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.6002278233.

Mann, William. The Operas of Mozart. Cassell, London, 1977, p. 366 (in chapter on Le Nozze di Figaro).

Moore, Ralph. A Selective Discographical Survey of Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro. Online at MusicWeb-International https://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2018/Jul/Mozart_Figaro_survey.pdf

Schonberg, Harold. The Lives of the Great Composers. Pg. 106. Norton. 1981.

Solomon, Maynard (1995). Mozart: A Life. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780060190460.

Tommasini, Anthony (2004). The New York Times Essential Library: Opera: A Critic's Guide to the 100 Most Important Works and the Best Recordings. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 128. ISBN 9780805074598. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

"The 20 Greatest Operas of All Time". Classical Music.