Building a Collection #26: Beethoven's "Appassionata" Piano Sonata

Including Recommended Recordings

Building a Collection #26

Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57 “Appassionata”

By Ludwig van Beethoven

________________________________________________

Welcome back! Or for any new readers out there, welcome! We have reached number 26 on our Building a Collection journey covering the top 250 classical works of all-time. Beethoven appears again, this time with his Piano Sonata no. 23 “Appassionata”. An epic work of struggle, conflict, and power, it is one of the most recorded piano works ever. After setting the context, we will review the list of the most recommended recordings.

Ludwig van Beethoven

Because biographical details about Beethoven have been discussed previously, in order to reduce length this post will not get into those details except for the circumstances surrounding the composition of the Appassionata piano sonata. If you are interested, there are some marvelous books on Beethoven you may want to explore, including:

Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph by Jan Swafford (2014)

Beethoven by Maynard Solomon (1979)

Beethoven: The Man Revealed by John Suchet (2013)

Beethoven: A Life by Jan Caeyers (2020)

Of course, there are mountains of resources online about Beethoven and his music, as well as entire institutions and organizations around the world devoted to the study of Beethoven’s life, his letters, and his music.

Piano Sonata no. 23 in F minor, Appassionata

Beethoven’s Piano Sonata no. 23, the Appassionata (or “passionate” in Italian), was completed in 1805 and is among the composer’s most well-known and popular works for piano and was dedicated to Count Franz von Brunswick. The time period when it was composed is often referred to as Beethoven’s “middle period”, or also his “heroic period” when he also composed his groundbreaking Symphony no. 3 “Eroica”, the Waldstein sonata, the Violin Concerto, the Razumovsky Quartets, his opera Fidelio, and Symphonies 4-8. It was a time of great triumph, but also tremendous trials for Beethoven. His deafness had started in 1798 and was gradually worsening. In 1802, Beethoven wrote his so-called Heiligenstadt Testament in letter form to his brothers which documents his hearing loss and thoughts of suicide. It was in that letter he resolved to continue on for the sake of his art. The letter was never sent and was found after his death. Around this time, he also famously declared his determination to “seize Fate by the throat; it shall certainly not crush me completely". Beethoven never became totally deaf and could hear speech and music as late as 1812. However, it did have a large impact on his ability to make a living as a conductor and soloist.

Beethoven did not give the Appassionata sonata its name, and some scholars are in disagreement whether he knew about the name during his lifetime, or whether it was given the name after his death. The most common story is that the name was given to the sonata in 1838 by a publisher, long after his death. In any case, the name could not be more appropriate for the work. It is indeed passionate and tumultuous, and its emotional core is very much evident throughout. This is music that storms the heavens and shakes its fist in rage at fate. Or at least that is what I hear…the music is aggressive and powerful in the first and third movements, with some relief coming in the second movement. There is very loud pounding on the keyboard in several parts, and by nature this is a work of dynamic extremes, contrasts, and intensity.

Technically, the Appassionata is one of the most demanding Beethoven sonatas for the soloist, alternating between passages of great force and passages of tenderness. The pianist is asked to stop and start on a dime multiple times, and tempos vary widely. The three movements are structured in a traditional format as follows:

Allegro assai

Andante con moto

Allegro ma non troppo – Presto

Timothy Judd from The Listener’s Club comments on each movement:

“The first movement (Allegro assai) begins with quiet, icy suspense and foreboding. A single, ominous arpeggiating line, set in octaves, descends into the depths of the piano and then rises. Spirited dotted rhythms suggest the military music of the French Revolution. Sudden, bold leaps in range occur throughout the Sonata, something made possible by the extended five-and-a-half octave range Sébastien Érard piano, acquired by Beethoven in 1803. After establishing the home key of F minor, the music breaks off and then returns a half step higher. Amid wrenching Neapolitan chords, these searching opening bars give us the sense of being “lost” harmonically. In the bass, a new voice emerges with the familiar “short-short-short-long” rhythmic motif we hear throughout Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, composed around the same time. At the end of the development section, the motif returns in a ferocious dialogue. When the recapitulation arrives a moment later, it is shrouded in a quiet, ghostly terror, with the addition of the deep, rumbling bass.

The second movement (Andante con moto) is a set of variations on a serene, chorale-like theme in D-flat major. The theme is so sublimely simple that it feels more like a progression of chords than a melody. Yet, it provides fertile ground for increasingly adventurous development. Throughout the four variations, the voices become liberated from their initial well-behaved chorale, wandering off in exciting directions.

A sudden, jarring diminished seventh chord shatters the tranquility, opening the door to a bridge to the final movement. Again, we hear the dotted rhythms of the French Revolution. The final movement (Allegro ma non troppo–Presto) is stormy and windswept. Quiet anxiety turns into the ghostly terror of the night amid piercing shrieks and low moans. Perpetual motion lines roll across the keyboard as dark, continuous sonic waves. The coda section turns into a wild peasant dance. The final bars bring the Sonata to a ferocious conclusion.”

Beethoven’s pupil Ferdinand Ries visited Beethoven in the village of Döbling, north of Vienna, where Beethoven was lodging during the summer of 1804. Beethoven and Ries went for walks in the Vienna woods, one of which was recalled later by Ries:

"We went so far astray that we did not get back to Döbling until nearly 8 o'clock. He had been humming, and more often howling, always up and down, without singing any definite notes. When questioned as to what it was, he answered, 'A theme for the last movement of the sonata [Op. 57] has occurred to me.' When we entered the room, he ran to the piano without taking off his hat. I sat down in the corner, and he soon forgot all about me. He stormed for at least an hour with the beautiful finale of the sonata. Finally, he got up, was surprised that I was still there and said, 'I cannot give you a lesson today, I must do some work'."

The sonata has elicited many comments over the years. Here are a few others:

"Here the human soul asked mighty questions of its God and had its reply."

Composer Hubert Parry

"I know nothing that is greater than the Appassionata; I would like to listen to it every day. It is marvelous superhuman music. I always think with pride - perhaps it is naïve of me - what marvelous things humans can do."

Vladimir Lenin, President of the Soviet Union

“This sonata is a great hymn of passion, which is born of the never-fulfilled longing for full and perfect bliss. Not blind fury, not the raging of sensual fevers, but the violent eruption of the afflicted soul, thirsting for happiness, is the master’s conception of passion.”

Sir Donald Francis Tovey, Music Theorist

Beethoven himself would consider his Appassionata his greatest work for piano until his later Piano Sonata No. 29 in B♭ major, Op. 106, “Hammerklavier” was composed. In any case, the Appassionata became one of several works by Beethoven that revolutionized classical music, and it takes its rightful place near the top of the list.

Recommended Recordings

When it comes to recordings of Beethoven’s Appassionata, there are simply so many outstanding recordings that choosing only one as the essential recording is too difficult and far too subjective. Therefore, I have listed two categories of recordings, those that rise to the level of greatness in my estimation, followed by good recordings that deserve to be heard but don’t rise to the same level.

It may be important to know my preferences regarding recordings of the Appassionata. I see this piece as essentially violent and tumultuous, and although it also has lyrical demands, especially in the second movement, if you take the loud outbursts and pounding out of the performance, the piece loses its full impact. I fully realize there will be listeners that don’t care for loud banging on the keys, or for pianists playing passages at headlong speed with strong dynamic changes. My response is that if you feel that way, then the Appassionata may not be for you. To be sure, there are many interpretive approaches that work for the Appassionata, but my preference is for pianists that bring out the extremes in dynamics and speeds, while also retaining enough clarity in articulation and holding the structure together through even the fastest passages. If the pianist doesn’t do some banging on the keys, the result is altogether too genteel for me. For all the power and intensity, the sonata demands, it also demands more than its fair share of sheer virtuosity, and a subtle touch.

The list I have gathered below favors pianists who keep the flow moving forward while also retaining the underlying pulse. Louder passages should indeed be loud, but not at the expense of the softer, more lyrical passages which must also be played clearly and convincingly. Drawing a distinct contrast between the louder and softer passages, particularly in the first movement, is critical. There is anger, despair, fury, resignation, calm, beauty, passion, violence, dissonance, and catharsis. I really don’t know any other piano work that takes us to such extremes.

The second movement Andante con moto is one of my favorite movements in all of music. Its beauty and simplicity masks what is surely not an easy movement for the pianist. The pacing and dynamic shadings are critically important to the overall structure and impact. Playing it too fast assures it will lose all sentiment whatsoever, while playing it too slow means it will lose all momentum and feeling. I like when the pianist varies the tempo to become gradually a bit faster with each variation rather than keeping the same tempo throughout. When done well, it is one of the most sublime creations you will ever hear.

In the final movement, Allegro ma non troppo - Presto, passion and drive are all-important, but so too are clarity and structure. If taken too fast, especially the conclusion, it turns into a mashup which can easily lose focus and notes get lost in the mix (at least for the listener). Pushing the tempo and dynamics toward the end is entirely appropriate, but we must be able to hear all the notes and understand the structure. Just my two cents as a reviewer.

A few other disclaimers. One, there are currently over 300 recordings of the Appassionata on streaming services, and that is not counting recordings that are out of print or unavailable. Although I have listened to a large number of versions, I have certainly not listened to them all, and so it is definitely possible there are some hidden gems out there I have yet to discover. Perhaps you have a favorite recording not listed below? If so, send me a note. I also don’t believe any one artist has said all there is to say about the Appassionata.

Second, you will not see the British piano prodigy Solomon Cutner (1902 - 1988), almost always referred to as simply Solomon, on my list below. His Beethoven sonata recordings are the stuff of legends, but I could not find a decent sounding recording of the Appassionata by him online or on streaming services. The consensus seems to be that Solomon’s recordings on the Testament label are the best sounding, and those are available at a cost. When I am able to fully survey Solomon’s Beethoven, I may go back and edit the list below.

Great Recordings

In chronological order:

Austrian-American pianist Arthur Schnabel (1882 - 1951) was the first pianist to record all 32 of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, put down between 1932 and 1935 at Abbey Road Studios in London. Besides being such a pioneering recording project, begun only a handful of years after the advent of recording technology, Schnabel also proves to be one of the finest Beethoven interpreters on record. His playing of the sonatas is intelligent, refined, with a blend of organic expression and technical mastery. The set is the benchmark by which all other complete sonata sets have been compared. As for his Appassionata, the outer movements are taken marginally faster than most recordings you will hear. The passion and power are there in spades, complete with abrupt transitions and extreme tempo and dynamic contrasts. There is an authority to the performance which words cannot fully describe. Schnabel was known to be rather sloppy at times with notes, and indeed you can hear some mistakes, but what comes out strongly is his innate sense of phrasing and dynamics. The recorded sound is very good for its time, but you must make allowances for the poor sound given the historical value of the recording. One of the limitations of the recording is in faster passages, including the run up to the conclusion in the final movement, there is sonic congestion which makes it difficult to hear clear separation in the notes. Schnabel also rips through the final movement rather breathlessly, which is thrilling but also makes me wish that technology had been more advanced at the time. In any case, this is distinguished playing, fully deserving of its reputation.

German pianist and composer Wilhelm Kempff (1895 - 1991) was especially known for his interpretations of Beethoven, and he recorded complete cycles of the 32 sonatas in 1951 and 1965 (both for Deutsche Grammophon), as well as other partial cycles in lesser sound going back before wartime Germany. Kempff was relatively conservative in his approach, eschewing displays of showmanship, and embracing moderate tempos. He was known to emphasize the lyricism of a work, but also the rhythmic pulse. There was often a spontaneity to his pianism that, when it came off, often shed new light on a work. Such is the case with his 1950s Appassionata from his mono complete Beethoven cycle. Good as his later recording is, it is the earlier effort that reaches greatness. Kempff’s playing is never over-the-top, and he gives his due to the Mozartian and Schubertian roots of this music. This could be described as cultured or aristocratic playing, and it is, but Kempff also pushes the action perceptibly more than on his later stereo set. There is more tension, more drama, and more forward push. But Kempff is also precise and clear, and every note is in place. There is a serenity to the slow movement that is very attractive, and Kempff does not pound you into submission in the outer movements. Still, there is no lack of passion. The piano sound is a little thin and distanced with a loss of range at the bottom, but perfectly listenable. You may want to know that some sources note that Kempff played at the behest of the Third Reich both before and during the war and was known to be a musical ambassador of sorts for the regime.

Soviet and Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter (1915 - 1997) is considered one of the greatest pianists ever, and his live Appassionata from 1959 in Prague (Praga Digitals) and his 1961 studio recording for RCA Living Stereo are both worthy of being on the great list. I have a slight preference for the live Prague recording because the sound is not as fierce as the RCA, but the performances are quite similar. Richter’s vision of the Appassionata is brutal, unrelenting, and propulsive. The anger and violence are delivered raw, and while a bit short on charm, Richter brings us to the core of the turbulent emotions present in this music. I read a review of Richter’s Appassionata which disparagingly likened Richter’s approach to Vladimir Putin’s ruthlessness. While not a fair analogy, Richter is indeed uncompromising in his single-minded vision to recreate what the composer intended. Richter draws you in, shakes you up, and leaves you in awe. The Andante con moto is taken faster than usual, but eventually I realized the wisdom of Richter’s approach, which fits within a greater overall structure. The final movement is incendiary and leaves one speechless. Richter’s other Appassionata recordings, live in Moscow 1960 and live at Carnegie Hall 1960, are certainly worth hearing but don’t quite reach the same level.

One of the very first compact discs I owned was a Vox records disc of the now 93-year-old Austrian pianist Alfred Brendel playing Beethoven’s Emperor piano concerto with the Vienna Symphony and a young Zubin Mehta conducting. Along with the concerto, it included Brendel’s early 1960s account of the Appassionata sonata. This early Brendel version is for me the most exciting and profound Appassionata he recorded, despite many critics (and Brendel himself) claiming that his later Beethoven has more depth and insight. Perhaps I am just being sentimental, but I find Brendel at the height of his abilities in both attention to detail as well as to the energy he brings to the outer movements. The middle movement is one of the best on record, and in the Presto of the final movement he never loses sight of the details even when pushing the tempo forward dramatically. Brendel’s playing here connects with me in a way I cannot really explain. There is some background hiss which is not bothersome. While Brendel’s later recordings have their own rewards, I will return to this one most often.

Austrian-American pianist Rudolf Serkin (1903 - 1991) was one of the most celebrated pianists of the 20th century, and while he did not leave us a complete Beethoven sonata cycle, he did leave us some excellent recordings of most of the “named” sonatas. Serkin’s stereo recording of the Appassionata in 1962 for CBS/Columbia (now Sony) remains one of the great recordings of the piece. Serkin was known for the consistency of his bass line left hand, combined with his dextrous melody driven right hand to create a wonderfully balanced sound. We hear that on this recording, as he brings a sweeping and energetic approach to the outer movements, all the while maintaining a noticeable rhythmic pulse underneath. Power and precision is alternated with refinement and elegance to make a most satisfying reading. Serkin is always sensitive to the musical line, and never tips over into excess. This is a performance that has stood the test of time. The sound is very good. Highly recommended.

Austrian pianist and composer Friedrich Gulda (1930 - 2000) was a sort of “bad boy” of the Vienna classical scene in the 1950s and 1960s. Equally talented as a jazz pianist, and intent on stretching the boundaries of classical music, not everyone was enamored with Gulda’s outside the box thinking. But the fact remains that Gulda was one of the most gifted pianists of the century, and it is no surprise that he also taught and mentored the great pianist Martha Argerich. Gulda recorded a complete Beethoven sonata cycle in the 1960s for the Amadeo label, variously repackaged and reissued by other labels, most recently on Brilliant Classics. The entire cycle is preferable to Gulda’s 1950s Decca recordings in that these readings are more urgent, leaner, and more rhythmically nimble. The Appassionata in particular is almost completely bereft of sentimentality and warmth, and that is a big part of why I like it so much. Gulda was never much of a romantic, but here he is totally unyielding in his approach. The playing is brisk, direct, and compact, even more so than Richter. The final movement is taken at a headlong pace, and never lets up. I find it exciting and convincing, but others may want more lyricism and heart. This would never be my only choice, and it represents only one side of this great work. But wow, what a performance it is.

Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau (1903 - 1991) was one of the best Beethoven interpreters of the century, and recorded several complete Beethoven sonata sets over the course of his career. Over the years, his fundamental approach did not change for the Appassionata, as he avoided an aggressive style and emphasized the more lyrical, colorful, and sentimental side of the composer. Arrau did not believe in banging on the keys for effect, but that the meaning and intent would be delivered through the music itself. He chose tempos that were slower than the norm for the Appassionata, but his skill in bringing out the purpose and the emotion in the music, and in shaping phrases revealed him as a true artist. Where some pianists’ approach is to add speed to underline the passion, Arrau rejected that idea. Rather, he was a master at shading and dynamic contrast, and became a poet with the notes. Arrau was well-known for his Chopin and Liszt, and he brings that sort of romantic sensibility to Beethoven as well. He is really an outlier in this list in the sense that he was never tempted to follow the trends in Beethoven, even in his last Beethoven cycle recorded when he was in his 80s. The best of his Appassionata recordings is from his 1960s complete cycle on Philips (now Decca), and that is because the sound is good but also Arrau had not slowed down too much yet, as he would on his last cycle. The earlier recordings, including the one on his EMI set from the 1950s, suffer from poor sound quality and I find it quite distracting. I urge you to listen to Arrau as a truly great artist who put his own stamp on the Appassionata.

A somewhat overlooked artist who recorded an outstanding Beethoven sonata cycle in 1970 is German-born American Claude Frank (1925 - 1914). Frank studied under Arthur Schnabel, but spent most of his career teaching at various universities and conservatories, as well as playing with the Boston Symphony Chamber Players. His Beethoven set was originally recorded by RCA Victor, and is now available on the Music & Arts label. His Appassionata is assertive without being bombastic, and the way Frank reveals the bass line and the inner voices of the piano is revealing. There is plenty of power and brio, and Frank seems to enjoy focusing on the more rhythmic points of the score. There is a heroic nature to Frank’s approach, and his outstanding balance of both the intellectual and emotional aspects is quite satisfying. The sound is excellent. I really enjoy this performance.

One of the very best recordings of the Appassionata, and many say THE best, is from Ukraine-born Soviet era pianist Emil Gilels (1916 - 1985). Gilels was one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, and he recorded almost all the Beethoven sonatas for Deutsche Grammophon. Many consider his nearly complete set the best available, with Gilels dying suddenly before he could record the last several sonatas. His Appassionata from 1973 has the piano recorded closely, leading to some very loud passages, fair warning to the listener. But the performance, though perhaps being equaled, has never been surpassed. It shows Gilels with a very assertive style, not dissimilar to Richter, highlighting the angst and turmoil in the music. Gilels is nearly perfect technically, his playing has an effortless and natural quality to it. There is warmth and humanity as well, and while Gilels avoids any vulgarity, he certainly gives the louder passages their due. Gilels’ Appassionata is fiery, and jumps out at you and holds your attention, and just as important he is also focused in the tender and reflective moments such as the second movement. This performance, and indeed the entire set, must be in the collection of any Beethoven lover.

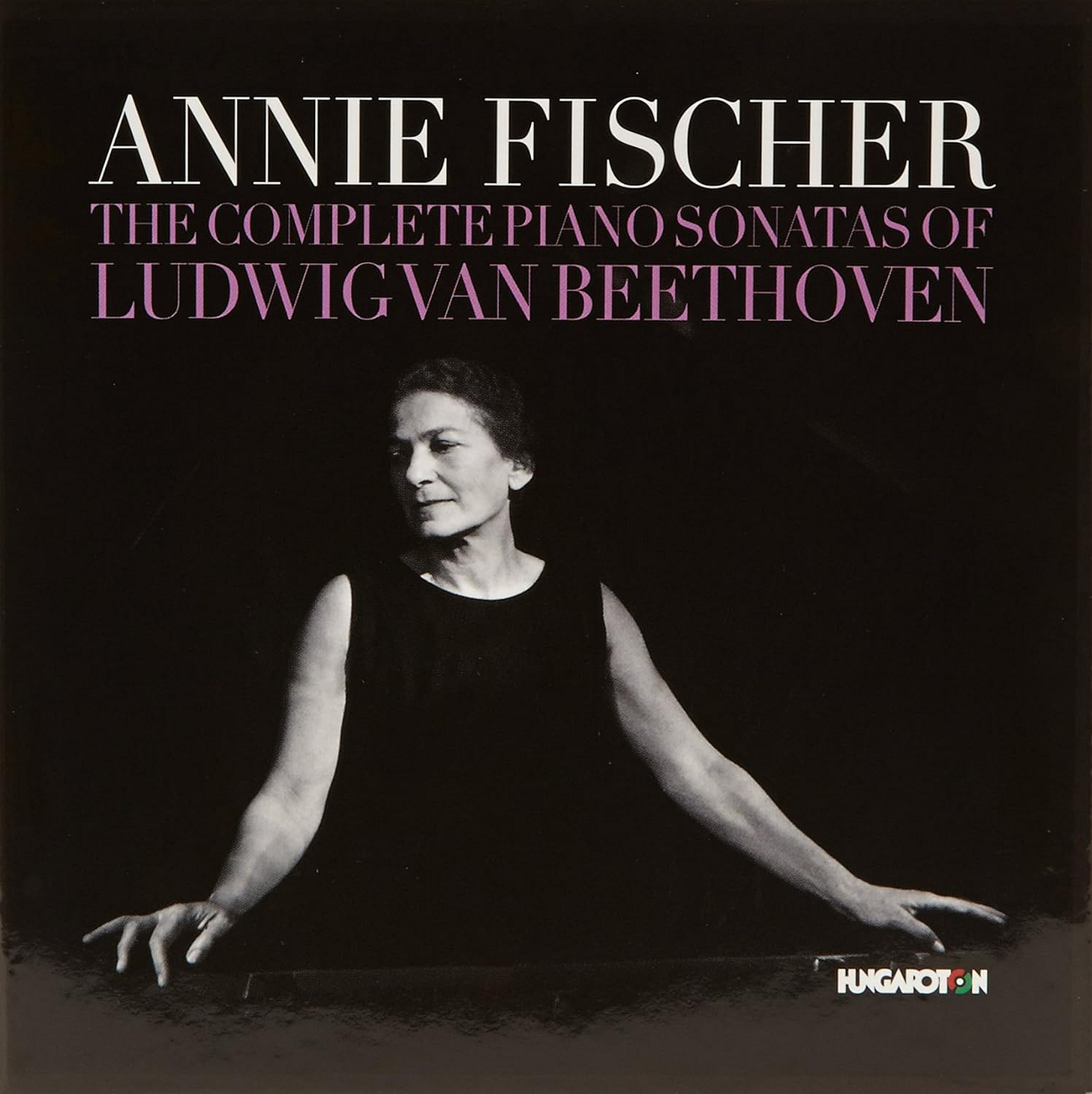

Any of you that followed my Top 50 Recordings of All-Time will recognize the great Beethoven sonata set from Hungarian pianist Annie Fischer (1914 - 1995). I absolutely love her Beethoven, and her Appassionata is no exception. Recorded in 1977 for the Hungaroton label, her Appassionata is deeply felt, well considered, powerful, and passionate. Tempos are fairly fast, but never rushed. Spontaneity was a hallmark of Fischer’s art, and the inspiration of the moment often brought out her best. This is stunning pianism of the highest order, bringing out all the colors, contrasts, and emotions of this epic sonata. Fischer knows how to build the drama, just sample her work at the 2’00 mark in the first movement, as well as at 7’03 in the final movement. Her power and authority in Beethoven are undeniable, and for me she reigns with Richter, Gilels, Brendel, and Schnabel at the top of the Beethoven hierarchy. An essential for Beethoven collectors.

Argentinian pianist Ingrid Fliter (b. 1973) rather unexpectedly rises to the top with her outstanding Appassionata recording from 2011 on EMI (now Warner). Fliter gives a red-blooded reading here which takes no prisoners, and is consistently engaging and exciting. In Fliter’s own words, “Beethoven was an extremist. He did not give any concessions or compromises. He was not afraid of showing himself as he was and as such made many enemies as well as friends, lovers and admirers. I am among the latter." Fliter is her own artist, never following others, and where it is difficult to record such a frequently recorded piece such as the Appassionata, she brings a unique flair. She is attentive to the dynamics and rhythmic variations more than most, and brings an extrovert energy to the outer movements. The recorded sound is a bit problematic, with too much reverberation. But don’t let that put you off from a great performance.

I have been a fan of American pianist Jonathan Biss (b. 1980) for quite some time, and I especially like his Beethoven recordings. He has recorded the Appassionata twice, but it is the one recorded as part of his complete Beethoven sonata cycle on the Orchid/Onyx/Meyer cycle released in 2014 which has the greatest impact. Biss has focused on Beethoven quite a lot in his young career, and in 2011, on Beethoven's birthday, he released the eBook Beethoven's Shadow, a 19,000-word meditation on the art of performing Beethoven's piano sonatas. Biss doesn’t do anything too off the beaten track in terms of tempos and dynamics, and so in that sense he is relatively conservative. Biss is technically perfect, and has a beautiful tone, but also emphasizes the fiery temperament and overall climate of the music. By using clarity, focusing on structure, and communicating directly, Biss is not as assertive as Gulda, Richter, or Gilels. Where needed, Biss delivers bite and sharpness, as well as a hefty volume, and he moves the story forward in a well-paced manner without spilling over into a frenzy. His Appassionata is strictly controlled and dynamically nuanced, while the Andante con moto shows a deft touch, and a moving emotional core. In the coda of the final movement, he is more considered and thoughtful than in his earlier EMI recording, but both versions are quite similar. I enjoy Biss’ entire Beethoven cycle quite a lot, and may even recommend it as a close second to Annie Fischer.

I once saw the French pianist Jean-Efflam Bavouzet (b. 1962) in concert with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (he played Richard Strauss’ Burleske), and I remember coming away extremely impressed. The feeling is similar with his Beethoven, there is just a feeling of “rightness” with Bavouzet’s moderate yet compelling approach. His complete Beethoven sonata cycle from 2014 on the Chandos label is quite recommendable, and boasts excellent sound. The Appassionata is one of the best performances of the set. Bavouzet here has a clean, dry sound and prefers to present to us Beethoven’s own score without intervening with his own thoughts or ideas. Bavouzet has a stately and elegant tone, but in the first movement he also becomes quite forceful and animated. The slow second movement builds gradually, and this is really the way I believe it is to be played, as the variations build on one another. The final Allegro is captivating and fresh, with Bavouzet avoiding any heaviness or histrionics. Another version to rival the very best, and once again the complete set of the sonatas is right up there with the most outstanding.

Finally there is the Appassionata from Russian pianist Igor Levit’s (b. 1987) very good 2018 complete set of the Beethoven sonatas. As a whole, the set is somewhat of a mixed bag, but the Appassionata is incredible. Reviewer Tal Agam notes that Levit’s overall timings of each movement are quite similar to Schnabel and Bavouzet, but his slower tempo for the middle movement means that the outer movements are marginally faster. This is an impressive performance, and Levit lives on the wild side, and if it ends up being a little rough around the edges, the result is very exciting. I admire Levit for taking risks, and where he comes across as more spontaneous, it really pays off. The Appassionata calls for just such an approach, and his approach is quite consistent with both Richter and Gilels in that it is an almost unforgiving approach. When it comes off well, as it does here, it is superb. The rest of Levit’s sonata set is less consistent, but definitely worth hearing.

Other Good Recordings

No doubt other listeners have favorites which are not on my list, but the best of many other recordings that are just a notch below greatness include those by (in no particular order): Wilhelm Backhaus (1958), Edwin Fischer (all versions), Stephen Kovacevich, Yu Kosuge, Arthur Rubinstein (1963), Walter Gieseking (1953), Daniel Barenboim (all versions), Maurizio Pollini (2003), Paul Lewis (2007), Richard Goode (2017), Frank Braley (2001), and Yevgeny Kissin (2017).

I realize this has been a very long post by now, so if you have made it this far, kudos to you. Thank you so much for your readership and support. I also want to welcome any new readers that have joined us on this journey. I hope you will read the next installment when we cover #27 on the Building a Collection list: Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring. See you then!

_______________________________________

Notes:

Agam, Tal. Review: Beethoven - Complete Piano Sonatas - Igor Levit. September 13, 2019. Online at theclassicreview.com.

Church, Michael. Jean-Efflam Bavouzet performs Beethoven Piano Sonatas. BBC Music Magazine. May 10, 2018.

Cooper, Barry (2008). Beethoven. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531331-4.

Cooper, Barry, ed. (1996). The Beethoven Compendium: A Guide to Beethoven's Life and Music (revised ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-50-027871-0.

Distler, Jed. Gratifying Beethoven Cycle From Jonathan Biss. Online at https://www.classicstoday.com/review/gratifying-beethoven-cycle-from-jonathan-biss/.

Distler, Jed. Beethoven Sonatas Frank. Online at https://www.classicstoday.com/review/review-8059/.

Distler, Jed. Beethoven: Sonatas/Gulda. Online at https://www.classicstoday.com/review/review-12309/.

Ealy, George Thomas (Spring 1994). "Of Ear Trumpets and a Resonance Plate: Early Hearing Aids and Beethoven's Hearing Perception". 19th-Century Music. 17 (3): 262–273. doi:10.1525/ncm.1994.17.3.02a00050. JSTOR 746569.

Greenberg, Robert. Music History Monday: Appassionata. Medium.com. February 18, 2019. https://medium.com/@rgreenbergmusic/music-history-monday-appassionata

Huizenga, Tom (21 March 2018). "The Pianist Who First Climbed Beethoven's Mount Everest". NPR. Retrieved 2019-03-15.

Judd, Timothy. Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 23 in F Minor, “Appassionata”: A Turbulent Drama. The Listener’s Club at https://thelistenersclub.com/2020/12/16/beethovens-piano-sonata-no-23-in-f-minor-appassionata-a-turbulent-drama/. December 16, 2020.

Kerman, Joseph; Tyson, Alan; Burnham, Scott G. (2001). "Ludwig van Beethoven". Oxford Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40026.

Lebrecht, Norman (18 June 2020). "The Emperor's Old Clothes". Retrieved 23 October 2021.

Morin, Alexander. Annie Fischer. Complete Beethoven Sonatas. Online at http://www.classical.net/music/recs/reviews/h/hgr31326a.php.

Pizarro, Arthur. The Beethoven Sonata Cycle. BBC Radio 3. https://www.bbc.co.uk/radio3/classical/pizarro/sonata23.shtml.

"The 20 Greatest Pianists of all time". Classical Music. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

Tommasini, Anthony (2014-12-28). "Claude Frank, Pianist Admired for Performing Beethoven, Dies at 89". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-01-01.

Whitmore, John. Review. Beethoven The 32 Piano Sonatas. Music Web International at https://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2013/Aug13/Beethoven_sonatas_Kempff_RRC9010.htm.

"Wilhelm Kempff Is Dead at 95". The New York Times. 25 May 1991.

I’ve heard most of the people on your primary and secondary list. Vladimir Ashkenazy recorded it three times. It’s his earliest recording that is much better than the others. His right hand in the coda is so good he makes everyone else sound crippled. And his first movement is very climactic, too. This is Ashkenazy at his best. The original CD had a picture of a sailboat. You can find the last movement on YouTube with that picture; YouTube reduces the sound quality.

I'm reading your great lists of recommendations bacwkard, and here there is one recording that I find missing: the one by Ronald Brautigam. His is perhaps the most universally acclaimed complete cycle of Beethoven's great 32. I realized that some people have an aversion to the fortepiano sound, and I myself am not a great fan of fortepiano. But Brautigam is so good, that it doesn't really matter.

I have recently heard another outstanding cycle of Beethoven's piano sonatas, by Paavali Jumppanen, but that is probably more controversial.