Building a Collection #18

Symphony no. 9

By Gustav Mahler

__________________________________________________________

“It is terrifying, and paralyzing, as the strands of sound disintegrate…in ceasing, we lose it all. But in letting go, we have gained everything.”

Leonard Bernstein commenting on Mahler’s Ninth Symphony.

Gustav Mahler

Most of what I’ve outlined below as a relatively brief summary of Mahler’s life was also used for Building a Collection #12, when we discussed his Symphony no. 5.

Gustav Mahler (1860 -1911) was an Austro-Bohemian conductor and composer from the Romantic era in classical music. Some people, me included, consider Mahler one of the greatest composers ever. Born in Bohemia (then part of the Austrian empire) to Jewish parents of humble means, Mahler first rose to fame as one of the leading conductors of his time. He became known later, and is known today, primarily for his compositions. The reason his music did not become more well-known sooner may be attributed to the fierce anti-Semitism present in late 19th and early 20th century Vienna, the musical capital of the world at the time. Another reason may be the reputation that Mahler’s compositions gained for being too long (indeed, a well-earned reputation!).

As a composer, Mahler occupies a space between the Austro-German romantic tradition prevalent in the late 19th century, and the modernism that emerged in the early 20th century. He entered the Vienna Conservatory in 1875 and studied piano, harmony, and composition. At the time he became an advocate for the music of both Wagner and Bruckner, two of the most well-known German composers of the day. He would later conduct both of their works frequently, despite Wagner’s notorious anti-Semitism. Mahler was a big part of the transition from the Romantic period to the Modern period in classical music, and he greatly influenced composers of the so-called “Second Viennese School” including Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern. Other famous composers very much influenced by Mahler’s music include Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, Dmitri Shostakovich, Kurt Weill, and Benjamin Britten.

Mahler’s conducting career began in about 1880, and around the same time he composed his first notable work, Das Klagende Lied (Song of Lamentation). His conducting career advanced quickly, and he took up posts in Kassel, Prague, Leipzig, and Budapest respectively. His conducting style was characterized by a dictatorial manner and perfectionistic demands, and even though he achieved a lot of critical acclaim, he was also despised by many musicians that played under him.

In 1897 Mahler took the helm of the Vienna Court Opera and then later the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. For a conductor, this was reaching the top of your field. Because of his responsibilities in Vienna, he had little time for composition, and generally only composed in the summers. Mahler built a series of “huts” out in the country, in places that inspired him, and he used the huts for composing. Soon he began presenting his compositions to the public, but the Viennese had a difficult time comprehending his first symphony and his large-scale song-symphony Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth). However, Mahler seemed to take the lack of acceptance in stride, believing that his time would eventually come.

In 1901, adversity arrived for Mahler. On February 24, 1901, he conducted a matinee of Bruckner’s Symphony no. 5, and then that evening he conducted Mozart’s The Magic Flute, a grueling day of work. Later that evening he suffered an intestinal hemorrhage and needed emergency surgery and nearly died. Shortly thereafter, he resigned from his post at the Vienna Philharmonic. Despite the hardships, Mahler returned to continue conducting at the Vienna Court Opera, and built a holiday home in Carinthia. The summer of 1901 was particularly productive for composition, and this included work on his Symphony no. 5 as well as Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children) and Das Knaben Wunderhorn (The Young Boy’s Magic Horn). In the fall of 1901, he met Alma Schindler. They would marry in 1902 and soon had two daughters. In general, this was a happy time for Mahler.

In 1907, Mahler resigned from the Vienna Court Opera because he was away so often and was beginning to gain more traction as a composer. He also wanted a break from the conservative Viennese music press, which had been consistently brutal in its treatment of Mahler. He accepted the post of principal conductor of New York’s Metropolitan Opera. However, shortly after accepting the post his four-year-old daughter died from scarlet fever and diphtheria, and he himself discovered he had some heart problems.

In New York, Mahler quickly gained audience approval and in 1909 he accepted the post of conductor of the New York Philharmonic, which he found agreeable to playing his own compositions. Despite career success such as the triumphant premiere of his Symphony no. 8 “Symphony of a Thousand” in Munich, his personal life suffered and his marriage with Alma began having problems. Even so, they stayed together and when Mahler became quite ill, Alma took him back to Vienna where he died on May 18, 1911, at the age of 50.

Symphony no. 9

Mahler’s Symphony no. 9 was written between 1908 and 1909 and was the last symphony he completed. The work was premiered on June 26, 1912, at the Vienna Festival by the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Bruno Walter. It has consistently been ranked as one of the greatest symphonies of all-time. The symphony uses a progressive tonal development, and thus cannot be said to be in one key signature only.

The symphony was written for a large orchestra, and the average duration of the entire symphony is about an hour and a half. It is laid out in four movements as follows:

Andante comodo (D major)

Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers. Etwas täppisch und sehr derb (C major)

Rondo-Burleske: Allegro assai. Sehr trotzig (A minor)

Adagio. Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend (D♭ major)

Unlike traditional symphonic structure, Mahler puts the slow movements at the beginning and end, while the faster movements are in the middle. As was somewhat typical of Mahler, one of the middle movements is a ländler, in the style of a popular Austrian folk-dance of the time.

Below is a description of the four movements of the symphony by Christopher H. Gibbs, the editor of Musical Quarterly (the oldest music history journal in the U.S.), taken from his excellent program notes for The Philadelphia Orchestra (and edited for length and content):

First movement

The opening rhythm, presented by cellos and a horn repeatedly intoning the pitch A, returns at crucial structural moments in the movement, including at the climax “with the utmost force”. As early as 1912 (and taken up by musicologist Deryck Cooke and Leonard Bernstein later) the rhythm was likened to the irregular heartbeat of a diseased heart (which Mahler was known to have at the time) ...A nostalgic D-major theme gradually emerges in the second violins, accumulating force through a series of fragments played by various instruments. The organic growth of the themes marks one of Mahler’s greatest compositional achievements. The composer Alban Berg noted, ‘The whole movement is permeated with the premonition of death…again and again it occurs, all the elements of worldly dreaming culminate in it…which is why the tenderest passages are followed by tremendous climaxes…’

Second movement

The second movement is a series of dances, and opens with a rustic ländler, which becomes distorted to the point that it no longer resembles a dance.

Gibbs continues:

Constantin Floros has called the second, which begins in the tempo of a relaxed ländler, the ‘summation’ of Mahler’s dance styles. Although it starts innocently, it takes on the flavor of a ‘Dance of Death’.

Third movement

The following Rondo-Burleske likewise offers a wide range of moods and ideas, including the gestures of popular music of the sort that brought charges of banality against Mahler. The movement shows Mahler’s increasing interest in counterpoint, taking his studies of Bach to new extremes. Fugato mixes with marches, grotesque and angry passages with more tender moments. A quieter, phantasmagorical middle section looks forward to the final movement.

Fourth movement

The final Adagio opens with a forceful unison violin theme reminiscent of the slow movement of Bruckner’s Ninth and Wagner’s Parsifal, both of which also project lush, hymn-like meditations. The music plunges into the key of D-flat major…All the Ninth’s movements, except for the furious coda of the third, end in disintegration, approaching the state of chamber music. The incredible final page of the Ninth offers the least rousing finale in the history of music, but undoubtedly one of the most moving…The music becomes ever softer and stiller, almost more silence than sound, until we may be reminded of the heartbeat that opened the Symphony, but now realize it is consciousness of our own heartbeat. In this extraordinary way Mahler implicates his listeners into the work, which ends dying away.

The meaning behind Mahler’s Symphony no. 9

Mahler died in 1911, before hearing his Symphony no. 9 performed. Some musical scholars interpret the ending of the symphony as Mahler’s farewell coming as it did after the death of his daughter Maria Anna and the diagnosis of his own heart problems. However, this interpretation is contradicted by Mahler being in good health while composing the work and that he had just finished successful seasons conducting the New York Philharmonic and the Metropolitan Opera. Nevertheless, it is impossible to avoid the idea that his Ninth was some sort of valedictory work. Death haunted Mahler going back to his siblings, the death of his daughter, and certainly the portending of death was implied in much of his music.

Mahler was rather superstitious and was apparently a believer in the so-called “curse of the ninth” that had claimed such composers as Beethoven, Schubert, and Bruckner after their ninth symphonies. Mahler had resisted numbering his work titled Das Lied von der Erde, even though it is widely considered a symphony, in order to avoid the curse.

Some have speculated that Mahler takes us through all the stages of grief in the Ninth, including denial, anger, and acceptance. Leonard Bernstein discussed the symphony in one of the Norton lectures and speculated that the final Adagio movement foreshadows three deaths: Mahler’s own death, the death of tonality in music, and finally the death of the “Faustian” culture in the arts (an idea from Oswald Spengler that the decline of culture in the west is tied to the loss of a classical or western perspective on the world as projected in the arts).

Composer Arnold Schoenberg said of Mahler’s Ninth:

The Ninth is most strange. In it, the author hardly speaks as an individual any longer. It almost seems as though this work must have a concealed author who used Mahler merely as his spokesman, as his mouthpiece

Composer Alban Berg commented on Mahler’s Ninth:

I have once more played through Mahler's Ninth. The first movement is the most glorious he ever wrote. It expresses an extraordinary love of the earth, for Nature. The longing to live on it in peace, to enjoy it completely, to the very heart of one's being, before death comes, as irresistibly it does.

Conductor Adam Fischer in the liner notes to his recording of the Ninth with the Düsseldorf Symphony says:

Mahler's Ninth Symphony is not about death, but about dying. Death and dying are two entirely different matters. While working on the Ninth, I realized that I know of no other language apart from German in which the words death (Tod) and dying (sterben) have entirely different etymologies. ... the finale is just one sole extended act of dying, the disintegration of life. The last section, particularly the last page in the orchestra score, describes that situation so perfectly that it surpasses any other depiction, whether it be in literature or the fine arts.

Conductor Herbert von Karajan said of the Ninth:

It is music coming from another world, it is coming from eternity.

Of course, not everyone agrees with the greatness of Mahler’s Ninth, and some have lamented that its great length is simply too long. I vividly recall bringing two of my closest friends to a live performance of Mahler’s Ninth at the Boston Symphony Orchestra several years ago, conducted by James Levine. Both of my friends were tortured by the seemingly never-ending symphony and complained afterwards about it being a marathon. Neither of them ever attended any concerts with me after that occasion. I felt very differently, and I tried to absorb every moment, and every note of the concert. But when you listen to Mahler, you just have to accept it is not easy listening. For my part, I now reserve Mahler for special occasions because it is so rich and involving that listening to it too often is too emotional.

Recordings of Mahler’s Symphony no. 9

Recordings of Mahler’s Ninth were difficult to come by before the long-playing LP came along, which was introduced by Columbia in 1948. But also, Mahler was not in favor with audiences or conductors until the second half of the twentieth century. Still there remains some very fine historical recordings of the Ninth.

Top recommendation

The lauded conductor Herbert von Karajan only began to deeply explore Mahler’s work over the last 16 years or so of his life, even though he had conducted some Mahler in the 50s and 60s. It is not completely known why Karajan avoided Mahler for so long, but there is speculation Karajan did not feel comfortable with the wide orchestra palette and emotional extremes called for in most of Mahler’s symphonies, or that he the fine line in Mahler between satire and tragedy made him uneasy. There was an admission on Karajan’s part that he didn’t fully understand the way Mahler would juxtapose sublime music next to grotesque or ridiculous passages.

Even though Karajan is not considered one of history’s great interpreters of Mahler by any means, once he did turn to Mahler, he did so with excellent results. The foremost case is his live 1982 recording of Mahler’s Ninth with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra on Deutsche Grammophon. Karajan had recorded the Ninth in 1979 in the studio using analogue sound for Deutsche Grammophon, and that recording remains very competitive. But this live digital recording, made just a few years later, has even more personality and vitality and indeed this second recording for Karajan won the Gramophone Award. The fact that Karajan even allowed the release of any live recording meant that he must have been completely satisfied with the results. Karajan was known to be a control freak when it came to the recording, taping, mixing, and remastering processes, so it is interesting that this live recording remains one of his finest moments on record.

Karajan is less of an interventionist in Mahler than say Bernstein or Horenstein, preferring to not go as far to the extremes. On this recording I feel he gets everything right. Emotional climaxes are appropriately thrilling, the tragedy is brought out in spades without spilling over into excess, and the Berliners are absolutely beautiful throughout. The balance and blend of instruments is almost unbelievable. The ebb and flow are mastered completely, and Karajan projects the emotional core of the music without adding any extra tricks. We can easily sense Karajan’s control over the proceedings, but the performance feels less micro-managed than is typical for him from the studio, and this is a good thing. The intensity and spontaneity are caught superbly, but Karajan is still faithful to the score, and brings a new standard of precision and accuracy. The sound is very good, thankfully not as glaring as the original release. I have an anti-Karajan bias, but in this case I must simply bow in front of greatness. This Ninth is a triumph.

Other recommended recordings

The recordings below are listed in chronological order by the year recorded. There is no shortage of excellent Ninths, so the ones listed are the ones I consider indispensable.

Mahler’s Symphony no. 9 was dedicated to, and first conducted by his friend Bruno Walter in 1912. Walter also made the first complete recording of the symphony with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (the orchestra that also premiered it), recorded live in 1938 and now available on Warner and possibly other labels. The primary significance of this recording is historical and political, as it was made just before the Anschluss and Walter’s expulsion. I include the recording here as a historical document, but as a performance it is simply not among the best even after accounting for the dated sound. The performance has a sense of haste and of going through the motions unfortunately. Walter would record the symphony again with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra in stereo in 1961 with much better results.

The first studio recording of the complete symphony was made by the great Mahler conductor Jascha Horenstein and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra (not to be confused with the more famous Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra), recorded in 1953 for Vox (available now on Vox Box Legends). The sound is in fairly good mono, and the orchestra is caught up close. This has the advantage of providing good detail, but we lose some of the overall perspective. Horenstein directs in such a way that we are able to hear different layers of the orchestra well, and he maintains thrust and tension quite well. As Mahler conductors go, Horenstein tends toward the rough and tumble, almost raw, rather stoic approach. You won’t find beautiful playing here for the sake of beauty. This is all of a piece with Horenstein, who wants to give us a glimpse of the entire journey the symphony will take. Horenstein was a master at taking a thread and linking it to others in a large structure in order to build toward the emotional climax. In the second movement, Horenstein brings out much more detail and irony in the music than most by using a deft touch with dynamics and tempos. In the third movement Rondo-Burleske, Horenstein follows Mahler’s instructions to keep the music feeling like it is on edge, with calamity lurking around every corner. The menace lurking is pushed forward in the picture, and pulled back extremely well. The finale Adagio is never forced, but rather allowed to proceed upon itself in a noble way. Horenstein draws intimate, but also darkly hued, playing from the musicians, and it really feels like we are drawn into this world of tragedy but also a deeper humanity.

Sir John Barbirolli leads a somewhat kinder and gentler sort of Mahler Ninth with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in a recording on EMI/Warner from 1964. The story goes that Barbirolli made a rare appearance with the Berliners in 1963, and on the programme was Mahler’s Ninth. Mind you, at the time Mahler was not a popular composer in the city of Berlin or among the orchestra. But it went so well, the orchestra asked to record the symphony with Barbirolli. Thus this recording was made, and Barbirolli essentially reintroduced the Berliners to Mahler. The entire recording is imbued with warmth and passion, and if there is more softness to the overall vision, when played with such a high level of commitment it works just as well as other sharper, more edgy readings. The first movement brings yearning strings, and a tempo that just feels right. There is passion to be sure, but it is surely regulated. Barbirolli is yet another conductor that came to Mahler relatively late, and yet that sort of life experience brings a great deal of insight into Mahler’s music in my view. The second movement is given a great deal of color and bounce, while the Rondo-Burleske takes us far away from the warmth of the first movement. This is much harsher, with the orchestra projecting the pain and terror the music calls for…the inner string playing of the BPO is quite impressive here, and is full of feeling. The furious, almost reckless surge to the end of the movement is thrilling. The Adagio was reportedly recorded at night, as Sir John thought the music not appropriate to be played during the day. It is an emotional final movement, one where Barbirolli elicits playing of immense depth and character from the BPO. There is a real catharsis in this conclusion, heartbreaking though it is. This is a really beautiful recording. The sound quality is very good.

Czech conductor Karel Ančerl recorded Mahler’s Ninth in 1966 with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra for Supraphon, re-released as part of the Ančerl Gold series in 2019. I really like the directness of Ančerl’s account, it is fresh and perceptive. The overall timing is quicker than most other top choices, but as one critic explained Ančerl approaches each movement as a series of episodes rather than each movement itself as a whole. This works quite well, and allows Ančerl to speed up when needed, then to slow down depending on the music. Mahler approved of flexibility in tempo, and it should be noted that in general performances of the Ninth have gradually become slower over the decades and so Ančerl is not very far off in his overall timings. This is a balanced approach which never lets the music become too self-indulgent, but also doesn’t go too fast which ends up sounding unfeeling and cold. The sound is very good vintage 60s stereo\, and it is clear the Czech orchestra is more than up to the task. The playing is sharp and crisp, without a hint of routine. Highly recommended.

One of the very best recordings of the Ninth ever made is by Bernard Haitink and the Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam, put down in 1969 by Philips (now Universal), released in 1970. The well regarded musicologist Deryck Cooke exclaimed upon its release that he had just heard the greatest recording of Mahler’s Ninth in the catalog, further on explaining that the reason he felt that way was that for the first time he was hearing MAHLER’s Ninth, rather than some conductor’s idea of Mahler’s Ninth. This was Haitink’s reputation throughout his career, that he was faithful to the composer. I had the privilege to see Haitink conducting in his later years in Boston, and he was especially good in Mahler and Brahms played live in concert. Unfortunately that satisfaction and excitement rarely translated to the same feeling in recordings. In fact, I often find Haitink reliable, but not too exciting. But in this case, a young Haitink gets everything right. The excellent analog recording quality, the warmth of the Concertgebouw acoustic, and the great care Haitink takes over the details all contribute to this recording rising to the top. Climaxes hit the listener hard, and while Haitink is rather dispassionate in general, the way he subtly changes dynamics and moods is delectable. Haitink injects the second movement dances with humor, irony, and an unsettled feeling that increases as it moves along. In the final movement, Haitink is masterly at keeping the musical line running through the entire way, but also at keeping a tight grip on things until the primary moments when the climaxes hit home with a great force. I believe this is perhaps Haitink’s finest moment as far as recordings go. Haitink recorded the Ninth again, live in 2011 with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra on BR Klassik, which was yet another impressive recording, and in great sound. But I still prefer the earlier effort.

As one of the 20th century’s greatest Mahlerians, and a constant advocate for Mahler’s music, Leonard Bernstein recorded Mahler’s Ninth twice commercially. His first recording was with the New York Philharmonic from 1965 on Columbia/CBS, his second was with the Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam from 1985 on Deutsche Grammophon. But it is a live concert broadcast on radio in Berlin on Bernstein’s only appearance with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in 1979 that was dug out of the archives and issued by Deutsche Grammophon after Bernstein’s death that has become the most recommended Bernstein recording of the Ninth. It is safe to say that Bernstein’s way with Mahler was essentially to never play it safe, and so what you get is Bernstein pushing the envelope to the extremes of both hysteria and resignation. First, regarding the sound there is a slight buzz in the background, and at times we hear audience noise as well as Bernstein’s own breathing and jumping around. Personally I don’t find any quibble with the sound, but others may disagree. Also, the playing of the BPO is not as immaculate as they were for Karajan in 1982, and indeed some critics have noticed there are even some missing notes from the trombones in one section. But nevermind that, the music-making here is electric and spine-tingling, and few other conductors could wring every possible ounce of emotion out of the music the way Bernstein could. Even if you disagree with Bernstein’s fundamentally heart-on-sleeve approach, you have to admit this is nothing short of riveting. Bernstein’s earlier New York recording is also worthwhile, though the Concertgebouw recording has sonic issues. There is also a video of a live recording of Bernstein leading the Ninth with the Vienna Philharmonic from 1971 that is highly recommended. But anyone that loves Mahler should not be without this live Berlin recording.

A bit of a dark horse candidate is the outstanding 2008 recording by the English conductor Jonathan Nott and the Bamberg Symphony (Bamberg, Germany) on the Tudor label, a co-production with BR Klassik. The sound is very fine, with great presence and warmth in giving more of a “concert hall” type of big picture sound. The first movement is quite broad at 29 minutes plus, but I never found it plodding or slow, and Nott is effective in making us hear the entire movement in one entire sweep. The inner two movements present playing of sharp incision, wit, and constant forward propulsion. There is plenty of excitement here too, as well as the required menacing sound leading to the turbulent conclusion of the Rondo-Burleske. The strings in the finale are brilliant, singing out beautifully. Nott, somewhat like Haitink, doesn’t play his cards too soon but rather waits for the appropriate moments to let things rip. Nott’s vision is rather expansive, as it should be in my view, and here we find playing of tremendous character that easily matches any other recording of this work. A real contender then, and a joy to hear.

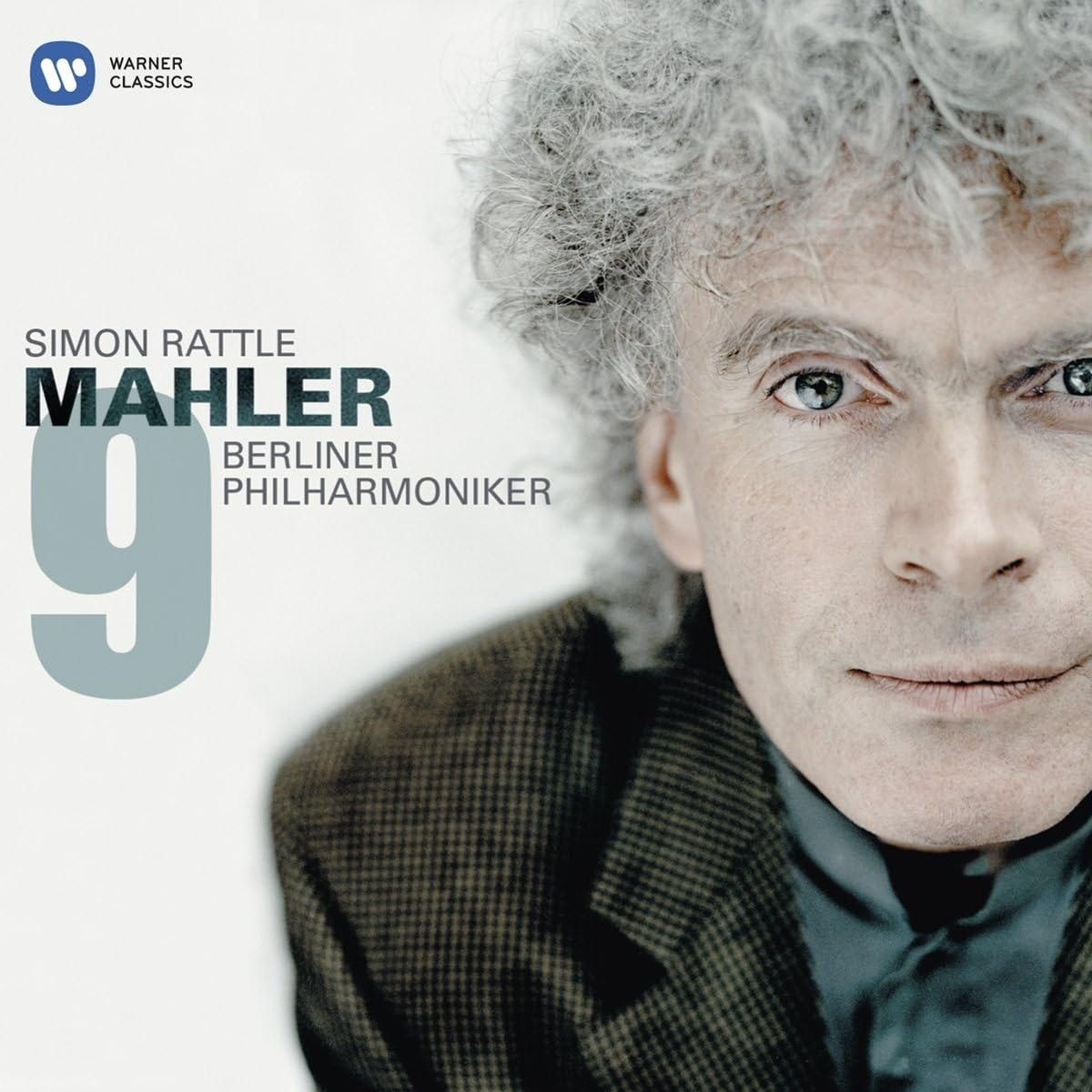

Finally in this list of the top recordings we have Sir Simon Rattle in his 2007 recording with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra EMI/Warner. As good as Rattle’s other two recordings of this work are (1993 with the Vienna Philharmonic and 2021 with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra), it is this second recording with the BPO that rises to the top. I’ve never been the biggest Simon Rattle fan, but on this recording I finally believe he lives up to his potential. What I mean by that is previously I found Rattle’s conducting to be highly derivative, and therefore not particularly convincing. But on this occasion, he brings a pleasing balance of both the cognitive and the spiritual aspects to the reading. He is neither too hot nor too cold, and really this brings great benefits. The sound here is also much better than in Vienna, and rather more natural and realistic than later in Munich. Rattle brings a lot of tonal color, clarity, as well as toughness that you expect from a great Mahler Ninth, along with the characteristically weighty Berlin sound that I really like in this music. Rattle also eschews some of the more modern trends toward steely strings and less expressiveness, instead choosing to create more of a traditional sound world allowing the strings to use more legato and to be more expressive. Having said that, Rattle never lets things go over the top and lets the music flow with its own energy. Meanwhile, at the moments where power and terror are called for, Rattle and the BPO bring down the hammer with great force. One of my complaints about Rattle on other occasions has been his tendency to overthink and overmanage, and while here he brings out a lot of detail in the score, I never get the sense that he is intervening too much. In each movement I found places to marvel at Rattle’s choices, which just felt right. A very satisfying reading.

My apologies to readers that will no doubt raise the question, where are the recordings by Klemperer, Abbado, Giulini, Solti, Boulez, Jansons, and Tennstedt among others? The truth is there are many other very good recordings out there, but subjectively the ones listed above are my top recommendations.

I look forward to next time when we will shift gears to discuss Mozart’s Requiem, number 19 on our Building a Collection survey. Until next time, best wishes for your health and happiness.

__________________________________________________

Notes:

Adorno, Theodor W. (15 August 1996). Adorno/Jephcott: Mahler. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226007694.

Bernstein, Leonard. The Unanswered Question.

de La Grange, Henry-Louis. Gustav Mahler, Vol. 4 – Oxford University Press, 2008.

Duggan, Tony. The Mahler Symphonies. A Symphonic Survey: Symphony no. 9. http://www.musicweb-international.com/Mahler/mahler9.htm.

Fischer, Adam. Quoted from his liner notes to Mahler: Symphony No. 9, Düsseldorf Symphony/Ádám Fischer – Avi-Music 8553478.

Gibbs, Christopher H. The Philadelphia Orchestra program notes. Mahler Symphony no. 9. 2019.

'Gustav Mahler', in New Grove Dictionary, Macmillan, 1980.

"Gustav Mahler". andante.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

Koch, Gerhard. Lieber die Schönheit als die Wahrheit. Eine vorübergehende Affäre: Karajans Auseinandersetzung mit Mahler, in: Jürg Stenzl / Lars E. Laubhold (Hrsg.), Herbert von Karajan (1908 – 1989) : der Dirigent im Lichte einer Geschichte der musikalischen Interpretation, S. 87. Also Peter Uehling claims that Mahler and the Viennese school are a repertoire never conducted by Karajan before 1972 (Peter Uehling, Karajan – Eine Biographie, Reinbeck bei Hamburg 2006, S. 157.

Osborne, Richard. Herbert von Karajan: A Life in Music.

Sadie, Stanley, ed. (1980). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 11. London, England: MacMillan. pp. 512–513. ISBN 978-0-333-23111-1.

Spengler, Oswald (1922). Decline of the West v. 2: Perspectives of World History. pp. 9–10.

https://mahlerfoundation.org/mahler/compositions/symphony-no-9/symphony-no-9-introduction/

Hi Tim, thanks for your note. I like the Blomstedt with Bamberg too, it is similar in some ways to the Barbirolli approach in that it is on the softer side. Completely valid, but I tend to like the more emotive conductors in Mahler. Blomstedt has made some great recordings in recent years. I particularly like his recent Schubert "Great" recording. I hope he keeps going until he is 100.

Hi Colin, thanks for catching the 2011 error. I need a proofreader!

Wow, what an opportunity to see Mahler live with Bernstein and the Concertgebouw. Nothing can take the place of that sort of experience.