“Music is enough for a lifetime, but a lifetime is not enough for music.”

-Sergei Rachmaninoff

Welcome back to Building a Classical Music Collection and the top 50 classical music recordings of all-time. It is hard to believe we are now at #40 on the list, and I really hope you have found some music you will return to often. There are still some great recordings coming up on the list, so stay tuned. For #40 I am highlighting Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto no. 3 in D minor Op. 30, in a recording by pianist Martha Argerich and the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Riccardo Chailly originally on Philips Classics (now Decca), recorded in December 1982. One of the most stunning performances of one of the most difficult of all piano concertos, performed live by Martha Argerich, whom I consider to be the greatest living pianist.

The Composer

Sergei Rachmaninoff (also often spelled Rachmaninov) was born in Semyonovo, Russia in 1873 and died in Beverly Hills, California in 1943. Rachmaninoff was one of those rare artists who excelled as both a performer and a composer. During his lifetime, he was known as one of the greatest pianists of all time and also the last great composer of the Russian Romantic tradition. Sergei was raised in a music-loving, aristocratic family and his mother fostered the natural ability he showed by giving him piano lessons. It was clear early on that Sergei possessed prodigious talent, and when the family fortunes declined they moved to St. Petersburg, where the boy entered the conservatory. Eventually as he continued to impress, he was sent to the Moscow Conservatory. There he received lessons from the strict Nikolay Zverev and his own cousin Alexander Siloti. As he grew in maturity and musical prowess, Rachmaninoff also made the acquaintance of many important and influential contacts in the music world.

Rachmaninoff became good friends with Tchaikovsky along the way, and the elder Tchaikovsky became quite an advocate for the young pianist. While at the conservatory, Rachmaninoff also displayed significant compositional gifts, eventually winning the gold medal in composition for his opera Aleko in 1892. Rachmaninoff was prone to depression, and when his Symphony no. 1 was received poorly in 1897, he went into an extended depression and withdrew from composing for several years. Later it was revealed that the orchestra for the premiere had been very poorly rehearsed and the conductor Alexander Glazunov had likely been intoxicated while on the podium. Rimsky-Korsakov remarked after hearing a rehearsal, “Forgive me, but I do not find this music at all agreeable.”

The assessment from Russian composer and critic Cesar Cui was the most cutting:

“If there were a conservatory in Hell, and if one of its talented students were to compose a programme symphony based on the story of the Ten Plagues of Egypt, and if he were to compose a symphony like Mr. Rachmaninoff's, then he would have fulfilled his task brilliantly and would delight the inhabitants of Hell. To us this music leaves an evil impression with its broken rhythms, obscurity and vagueness of form, meaningless repetition of the same short tricks, the nasal sound of the orchestra, the strained crash of the brass, and above all its sickly perverse harmonization and quasi-melodic outlines, the complete absence of simplicity and naturalness, the complete absence of themes.”

A later reassessment of the symphony would redeem it from its dismal initial reception, but the blow would haunt Rachmaninoff for the rest of his life.

In his depression, Rachmaninoff turned to hypnosis, which provided some relief. After a four-year period of self-doubt, Rachmaninoff returned with a huge success in his Piano Concerto no. 2 in 1900-01. The concerto almost assured him of lasting renown, with its large romantic melodies and virtuosic piano runs and climaxes. In popular culture, Frank Sinatra used themes from the first and third movements respectively for his songs “I Think of You” and “Full Moon and Empty Arms”. Perhaps more familiar is Eric Carmen’s 1975 ballad “All by Myself” based on the second movement.

His career resurrected, and after marrying his first-cousin Natalya Satina in 1902, Rachmaninoff would go on in the first decade of the new century to compose some of his most well-known and enduring works: Isle of the Dead (1907), Symphony no. 2 (1907), and his Piano Concerto no. 3 (1909).

Keep in mind that Rachmaninoff was not really making a living from composing, but rather from performing as a pianist and conductor. In 1904, Rachmaninoff agreed to become the conductor of the famed Bolshoi Theatre for two seasons. As a conductor, Rachmaninoff received mixed reviews as musically discerning but also very demanding and exacting of his players. During his second year in the post, he tired of the job and handed in his resignation in February of 1906. Unhappy with the political climate in Russia at the time, he packed up his family and moved them to Dresden, Germany, where they stayed until 1909. During this time, Rachmaninoff completed work on his Symphony no. 2 and it premiered in 1908. It was to become his greatest orchestral success.

During his time in Dresden, Rachmaninoff also agreed to travel to the United States for the first time to perform as a soloist and conductor in a series of concerts in 1909-10 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and conductor Max Fiedler. While preparing for the trip, he worked on a new concerto which would become his Piano Concerto no. 3, which he hoped to premiere on the trip. He ended up performing 26 times, 19 as a soloist and 7 as a conductor. Interestingly, his first appearance for recital was at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts on November 4th, 1909. Shortly after he gave the second ever performance of his Piano Concerto no. 3 as the soloist accompanied by the New York Symphony Orchestra conducted by legendary conductor and composer Gustav Mahler. This would be one of Rachmaninoff’s most memorable moments in the United States.

Upon his return to Russia in 1910, Rachmaninoff was appointed the head of the Imperial Russian Musical Society, but eventually resigned when he discovered that an administrator was dismissed for being Jewish. In the following years, he would compose The Bells and his All-Night Vigil as World War I heated up. Rachmaninoff went on tours in England and Europe performing his own works and for the first time including works by other composers. In February 1917, at the beginning of the Russian revolution, Rachmaninoff returned to his estate in Ivanovka only to find it had been confiscated by the Social Revolutionary Party. Rachmaninoff left within weeks, and vowed never to return. After a vacation in Crimea with his family, they moved to Moscow and lived in a collective for a time amid chaos and violence outside their doors.

Soon after, Rachmaninoff received offers from Scandinavia to perform recitals, which he quickly accepted mostly for the purpose of obtaining permits for his family to leave Russia. Packing lightly, and traveling through Finland by train and sled, they eventually arrived in Stockholm and then settled in Copenhagen. During this time, Rachmaninoff mostly performed live in recitals throughout Scandinavia as a means of income. As a result, he had to learn many new pieces by other composers, which greatly increased his repertoire. Despite receiving offers from the United States to conduct the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and to tour giving recitals, Rachmaninoff declined all of them. But he changed his mind after realizing that the United States could be financially advantageous for his family. He found a way to raise enough money for his entire family to travel from Oslo, Norway to New York City on the SS Bergensfjord.

Rachmaninoff toured extensively in the USA, and began an exclusive relationship with the Steinway piano company. Soon finances were no longer an issue, and the family lived quite well in New York City with many of the luxuries of the day. Rachmaninoff also began a recording relationship with RCA Victor in 1920, which would carry on through the rest of his career. He would also become well off enough to periodically send money to friends and family in Russia that were suffering through the Revolution. In the early 1920s, Rachmaninoff would tour widely in England and Europe, solidifying his fame. In 1924, he once again declined to be the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Leaving his home country had blunted his desire to compose, and he didn’t compose again until 1930 when he was spending summers in France. He would compose his well-known Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini there in 1934. Rachmaninoff would sign on to an article in the New York Times denouncing the cultural policies in the Soviet Union, and as a result he was boycotted from entering the country.

In his remaining years, Rachmaninoff would continue to perform and compose, albeit at a much slower pace. Various health issues arose, and eventually he was advised by his doctor to move to a warmer climate. In 1942 he moved with his family to Beverly Hills, California. By this time, Rachmaninoff had befriended Vladimir Horowitz and Igor Stravinsky, both of whom had also fled their homelands to the USA. The 1942-43 season would be his last season of performing, and even though he was still brilliant, he was very fatigued. He passed away in March 1943, a few days short of his 70th birthday. In his will, Rachmaninoff had requested to be buried in Russia, but since he had become a US citizen that was impossible at the time. In August 2015, Russia requested that Rachmaninoff’s remains be moved back to his homeland because they contended America had neglected his burial place, but had profited commercially from his name. His descendents have resisted this request, claiming that Rachmaninoff had chosen to make the USA his homeland after political exile from the Soviet Union. His remains are buried in Valhalla, New York.

As a pianist, Rachmaninoff was known for his precision, clarity, and consistent legato line (legato means smooth or flowing). Rachmaninoff’s hands themselves became something of a legend as well, since he had enormous hands and a very wide span with his fingers. He was able to play even the most difficult chords with ease, and he had an unbelievable ability to make full use of the keyboard. There is speculation Rachmaninoff suffered from acromegaly, which could explain his large hands and feet, as well as his depression.

The great pianist Arthur Rubinstein commented on Rachmaninoff the pianist:

“I was always under the spell of his glorious and inimitable tone which could make me forget my uneasiness about his too rapidly fleeting fingers and his exaggerated rubatos. There was always the irresistible sensuous charm…”

Author Max Harrison said:

“Rachmaninoff often sounded like he was improvising, though he actually was not. While his interpretations were mosaics of tiny details, when those mosaics came together in performance, they might, according to the tempo of the piece being played, fly past at great speed, giving the impression of instant thought.”

Rachmaninoff believed in tonal color, for as he said "interpretation demands something of the creative instinct. If you are a composer, you have an affinity with other composers. You can make contact with their imaginations, knowing something of their problems and their ideals. You can give their works color. That is the most important thing for me in my interpretations, color. So you make music live. Without color it is dead."

The music Rachmaninoff composed is noted for its highly romantic style, beautiful and memorable melodies, and rich harmonies. There is no doubt his career as a pianist greatly influenced his compositions, especially as he created so many works for solo piano. His early works were influenced by Tchaikovsky, whom he revered, but soon he would find his own voice and style that became very recognizable. Rachmaninoff’s use of changing rhythms, sweeping lyricism, and compact use of themes. His melodies are passionate and unabashedly sentimental, and as he grew as a composer he became more adept at contrasting orchestral color and textures. He was also a master of counterpoint and fugue, and used it well. Much of his structure was related to his love of Russian choral music, and this can be heard in almost all his works, especially his use of chords spaced apart for effect.

While certainly tonal in nature, Rachmaninoff’s music also contains an original style and genuinely sounds modern due to his use of chromaticism between tones and his careful use of dissonant harmonies. While some early critics said his works were shallow, gushing, and artificial, most now agree that Rachmaninoff’s greatest works are likely to endure forever.

Piano Concerto no. 3

Rachmaninoff premiered his Third Concerto with the New York Symphony Orchestra with Walter Damrosch conducting on November 28, 1909. For a long time, the concerto took a backseat to his Second Concerto, which was more melodic and concise. The Third Concerto is a deeper and more difficult work, with more virtuosic passagework and lengthier cadenzas. Unfortunately Rachmaninoff was compelled to make some significant cuts which made it shorter and easier to play in concert, but shortchanged much of the work’s artistic value. In the last 30 years or so, most concerts have included the full, unabridged original score, which pushes the timing to around 45 minutes total.

The concerto is structured as follows:

Allegro ma non tanto

Intermezzo. Adagio

Finale. Alla breve

Rachmaninoff claims the opening of the concerto “wrote itself”. As described by Robert Cummings in the All Music Guide:

“The concerto begins in a hushed, mysterious way with the piano playing out a simple but solemn theme of Russian character, which then immediately begins to sprout new ideas. A bridge passage leads to the second theme that is slower, but then takes on another form, and in a typical Rachmaninoff way is soaring and ecstatic. The main theme returns with a strong development section that leads into a fairly long cadenza, where Rachmaninoff offers the soloist two different versions: the chordal original, which is commonly notated as the “ossia”, and a second one with a lighter, toccata-like style. Finally, there is a restatement of the main theme and a brief coda which is subdued and reflective.

The second movement Adagio is formally rather unique, with the main theme dominating most of the movement, and a brief scherzo-like section appearing near the ecstatic glory of its big restatements by piano and orchestra in the middle part of the movement. After the playful scherzo-ish music, the piano is given a brief but brilliant cadenza that leads directly into the colorful finale.

The finale, marked Alla breve, offers a typical Rachmaninoff fast theme on the piano right off immediately following a loud chord from the orchestra: it is related to the first movement’s second theme and is rhythmically buoyant and catchy in its repeated notes. A rhythmic chordal passage harkens back to the rhythm heard at concerto’s outset, and a lovely theme, related to the first movement bridge passage, is presented, hinting at triumphant resolution. Following a dramatic, suspenseful buildup near the end the theme makes one final and absolutely triumphant appearance, after which the brilliant coda closes the work.”

The piece ends with the same four-note rhythm – claimed by some to be the composer's musical signature – as it is used in both the composer's second concerto and second symphony.

You may recall the concerto is significant in the 1996 film Shine, based on the life of pianist David Helfgott. The concerto is scored for solo piano and an orchestra consisting of 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets in B-flat, 2 bassoons, 4 horns in F, 2 trumpets in B-flat, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, snare drum, cymbals, and strings.

Rachmaninoff called the Third the favorite of his own piano concertos, stating that "I much prefer the Third, because my Second is so uncomfortable to play." Nevertheless, it was not until the 1930s and largely thanks to the advocacy of Vladimir Horowitz that the Third Concerto became popular. The “Rach 3” as it is sometimes called, is widely considered to be one of the most difficult concertos in the repertoire, and one which many virtuosos choose for competitions in order to highlight their talent.

The Recording

The Argentine pianist Martha Argerich, now 81 years of age, is considered to be one of the greatest pianists of all time. Her paternal lineage is Spanish in heritage, and her maternal lineage is Russian Jewish. A gifted child prodigy, she began taking lessons at the age of three and by five was taking lessons from Vincenzo Scaramuzza who taught her the importance of not just playing the notes but playing with lyricism and feeling. She gave her debut concert in 1949 at the age of eight.

The family moved to Europe in 1955, where Argerich began taking lessons with piano legend Friedrich Gulda in Austria, whom Argerich maintains was one of her biggest influences. In 1957, at sixteen, she won both the Geneva International Music Competition and the Ferruccio Busoni International Competition within three weeks of each other. Following this success, Argerich tried to study with legendary but eccentric Italian pianist Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, but only had four lessons in 18 months with him. Discouraged, she moved to New York City hoping to connect with her idol Vladimir Horowitz, but failed to meet him. She considered giving up the piano altogether, but was convinced by friends to stick with it. Following her return, Argerich won the prestigious VII International Chopin Piano Competition in 1965 at the age of 24.

Embarking on a professional career, she debuted in the United States in Lincoln Center's Great Performers Series. In 1960, she had made her first commercial recording with Deutsche Grammophon, which included works by Chopin, Brahms, Ravel, Prokofiev, and Liszt; it received critical acclaim upon its release in 1961.

Argerich has been disciplined in only performing music by composers she feels a particular connection, among those are Chopin, Beethoven, Rachmaninoff, and Schumann. Beginning in the 1980s, she began to refuse to play solo recitals and generally limited her performances to chamber music or concertos. In addition to her performances and recordings, Argerich has been the director of music festivals in Lugano, Lake Como, Italy and in Beppu, Japan.

Argerich is somewhat allergic to the limelight and tends to avoid the media whenever possible. Nevertheless, her performances are almost always widely acclaimed. She has worked hard to advocate for younger artists she has worked with, and has performed and recorded with many of them. In her personal life, Argerich has been married twice: first was to composer Robert Chen (with whom she has a daughter, violinist Lyda Chen-Argerich), and second to star conductor Charles Dutoit (with whom she has a daughter Annie Dutoit). Neither marriage lasted very long, and she had a non-marital relationship with pianist Stephen Kovacevich (with whom she also has a daughter Stephanie Argerich).

Argerich speaks Spanish, French, Italian, German, English, and Portguese and even though her mother tongue is Spanish, she insisted on speaking French to her children at home. She holds Argentine and Swiss citizenship.

Argerich is also a cancer survivor, having been diagnosed more than once, but has been in remission since about 1995.

I had the good fortune to see Argerich perform live at Boston’s Symphony Hall several years ago. It was the first, and only, time I have seen an artist receive a standing ovation before the concert began, just for walking onto the stage. She performed Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto no. 3, one of her favorites, and of course there was spontaneous thunderous applause at the end.

At the time of this recording of Rachmaninoff’s Third Concerto in 1982, Argerich was already a legend. We are very fortunate to have this recording of her doing the Rach 3, as she would soon thereafter stop playing it (and to my knowledge she has never played or recorded Rach 2, to the chagrin of her fans). This live recording was made by Philips with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and Riccardo Chailly in 1982.

As Bryce Morrison says in the liner notes for the CD:

“Rachmaninoff’s Third - arguably the most daunting and opulent of all piano concertos - has become inseparable in many musician’s minds from Martha Argerich, one of the few living pianists able to not only tame but dominate and engulf music of the highest passion and pianistic intricacy. Such a statement invites comparisons with other celebrated interpreters of this magisterial example of fin-de-siecle Romanticism; with the composer himself, Horowitz, Gilels, and Van Cliburn…Sensuous, impulsive and with moments which will make even the most blase listener or virtuoso fancier pale, Martha Argerich remains acutely sympathetic to Rachmaninoff’s idiom, to subtlety and rhetoric alike, while at the same time conveying her own inimitable force and individuality.”

Indeed, it is Argerich’s passion and feeling which stand out from other rival recordings, and for me, raise this recording to the very best. Argerich’s extrovert style is not to everyone’s liking, but in my view she supplies exactly what is required of this piece. As with almost any live recording, there is some background noise and a few coughs, as well as a few minor blemishes from Argerich herself (but precious few). I would contend it is all the more stunning as a result of being a live recording, catching Argerich at her most volatile and blazing. This is playing of the highest order in terms of pure virtuosity, but also musically in my opinion. The Third Concerto is meant to be played at high voltage with fire in the belly. And so it is by Argerich. There is a fearlessness to her playing, and a larger than life vision of the work that pulls and pushes us through emotional doors at every turn. Her mastery is just as evident in the large chordal writing as it is in the rapid fire light-fingered passages.

The opening Allegro ma non tanto belies what is to come, as it is taken at a relatively relaxed pace by Argerich. There is some sparkling playing here, sample at 5’14” the incandescent passage she creates. Around 7’00” minutes in, she begins to accelerate and crescendo building momentum toward the climax which arrives at 8’30”. This is clear, precise, and emotional playing. Again, at 10’40” she is playful and brilliant, arriving at another shining moment at 11’10” as the piano roars as it should. From 13’01” onward, Argerich displays amazing accuracy in the fast passages, and in the trills that lead through to the coda and the subdued, if mysterious, end of the movement.

In the Intermezzo, at an adagio, Argerich shows her astounding lyricism and interpretive vision. When the mood changes abruptly at 4’20”, you really feel it. At 5’18” she launches into a lush, romantic theme which shortly after is full of anguish and strain until about 6’55” where we begin to hear a hint of release and possibility. There is an increase in speed and dynamics until the climax at 7’18”, which feels triumphant. The fast passages and trills beginning at 8’28” sound effortless but then we know there are fireworks still to come.

But it is the finale which has never been equaled, except perhaps by Horowitz. We are struck with the sharp orchestral chord to begin the movement followed immediately by the sudden and aggressive passagework that Argerich seemingly takes in stride with verve and clear articulation. While it is true that Argerich takes many sections of the finale at a faster pace than almost anyone else, it is also true that the music holds up to this treatment and at no point does she lose the musical line. But she definitely pushes the envelope, which is thrilling. It is an edge of the seat experience, and one can hardly fault the RSO Berlin and Riccardo Chailly for barely keeping up with her (especially near the beginning about 1’00” into the movement where the orchestra is clearly behind her). Even the more restful or playful moments are imbued with urgency by Argerich, although she does pause during the extended middle section to savor Rachmaninoff’s writing.

Her playing at 6’15” is full of tenderness and subtlety, and the section at 7’25” is stunningly beautiful and impressive. Her forward push and assertiveness are never far away however, and at 9’00” she begins to push the tempo a bit more and again keeps moving forward, with the orchestra keeping up this time! This is music of sweeping grandeur and majesty, and the building up and fading back at 9’56” will eventually lead us to several fast runs and chords full of bravura at 11’05” and a large building up of tension with the orchestra. At 11’45” we are heading into the coda, which Argerich takes at a fairly moderate pace, at least giving the orchestra a chance, and in the recording the upper registers of the piano are captured quite well as Rachmaninoff pushes the soloist to the limit in the closing bars. The signature final four-note riff at the end is ecstatic, and clearly those attending the performance agreed that this was truly a remarkable performance.

We cheer at this fiery performance by Martha Argerich, a true force of nature, and are grateful to have this recording which fortunately captured this historic concert.

There are, of course, other notable recordings of the Rach 3.

Other recommended recordings

When it comes to recordings of Rachmaninoff’s Third Concerto, the competition is really between Rachmaninoff’s own recording, Horowitz’s 1951 Carnegie Hall recording with Fritz Reiner, and the featured Martha Argerich recording.

Rachmaninoff’s recording with The Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy from 1939-1940 take precedence for many listeners and critics. It has been remastered a few times, and the most recent remaster generally improves upon previous ones, but for me this is still difficult to listen to all the way through due to piano being distant. Rachmaninoff was unquestionably one of the most gifted pianists of his day, but for me this still comes up short of Argerich in terms of voltage. However, the interpretation is very interesting and deserving of the accolades it has received.

Vladimir Horowitz was probably the best interpreter of Rachmaninoff that has ever lived. After hearing Horowitz's performance of his 3rd concerto on August 7, 1942 at the Hollywood Bowl, Rachmaninoff said, "This is the way I always dreamed my concerto should be played, but I never expected to hear it that way on Earth." There are at least four recordings commercially available of Horowitz playing the Third Concerto: The 1930 recording with Albert Coates and the London Symphony Orchestra (hard to find, but it is available to stream on Spotify in a new remastering with decent sound), a 1941 recording of Horowitz with the New York Philharmonic conducted by John Barbirolli on various small labels, the 1951 recording from Carnegie Hall with Fritz Reiner and the RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra on the RCA Victor label (now Sony), and the 1978 recording with the New York Philharmonic and Eugene Ormandy at Carnegie Hall on RCA. The 1951 recording finds Horowitz at his most inspired, even though the sound is not ideal. I very much enjoy his 1930 recording with Coates, though it is not as fiery. The 1941 has sound limitations which disqualify it in my view.

Byron Janis (a pupil of Horowitz) and the Boston Symphony Orchestra with Charles Munch on RCA Living Sound, recorded in 1957 deliver one of the best versions of this concerto. Janis is crystal clear, and the orchestra is caught with detail and warmth. While not quite as fast or impulsive as Argerich, this is a very satisfying account. I prefer this to Janis’s other recording on Mercury Living Presence with the London Symphony and Antal Dorati, although that one is also very good.

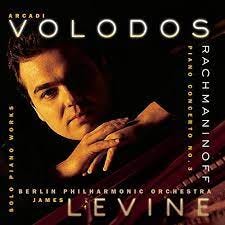

Russian pianist Arcadi Volodos with the Berlin Philharmonic and James Levine, released in 2000, is an outstanding choice for Rach 3. This is big boned, exciting, precise, and impressive. Not quite as hard-driven as Argerich, which may be a good thing in that Volodos and the orchestra bring out a lot of detail heard well in the excellent sound. Volodos also has a lighter touch overall than Argerich, but still has plenty of power. I would say Volodos sounds flawless, but perhaps is slightly less involving than Argerich.

American hero Van Cliburn, winner of the inaugural Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958 during the Cold War, making headlines and spawning ticker-tape parades upon his return, recorded the Rachmaninoff Third Concerto live at Carnegie Hall on RCA Living Stereo with the Symphony of the Air led by Kirill Kondrashin to commemorate his return to the USA. This is a more lyrical, less frenetic performance, but still caught extremely well and displays the tremendous gifts Van Cliburn possessed as a young man. Sound is outstanding for 1958, especially in the notoriously difficult recording venue of Carnegie Hall. It is a truly beautiful recording. It is worth noting that Van Cliburn’s actual winning performance in the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow, also of Rachmaninoff’s Third Concerto, was recorded and is available on the Testament label for a tidy sum. Kondrashin was also the conductor, leading the Moscow Philharmonic. I have not heard that recording, but I saw today it is available for mp3 download on Amazon for far less money.

At this point I need to wrap things up, and I apologize for this very lengthy post. I hope you will indulge me a bit due to my love for this concerto in particular. Have a wonderful Thanksgiving holiday, and I will see you here next time!

_____________________

Notes:

Bertensson, Sergei; Leyda, Jay (2001). Sergei Rachmaninoff – A Lifetime in Music (Paperback ed.). New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21421-8.

Brennan, Gerald. Dettmer, Roger. Reel, James. Schrott, Allen. Woodstra, Chris. All Music Guide to Classical Music, The Definitive Guide. All Media Guide. Pp. 925-926. Backbeat Books, San Francisco. 2005.

Cobb, Gary. "A Descriptive Analysis of the Piano Concertos of Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-04. Retrieved 2020-07-06.

https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/144683.Sergei_Rachmaninoff

Harrison, Max, Rachmaninoff: Life, Works, Recordings (London and New York: Continuum, 2005). ISBN 978-0-8264-5344-0.

Kyui, Ts., "Tretiy russkiy simfonicheskiy kontsert," Novosti i birzhevaya gazeta (17 March 1897(o.s.)), 3.

Lyle, Watson (1939). Rachmaninoff: A Biography. London: William Reeves Bookseller. ISBN 978-0-404-13003-9.

Martyn, Barrie, Rachmaninoff: Composer, Pianist, Conductor (Aldershot, England: Scolar Press, 1990). ISBN 978-0-85967-809-4.

Mayne, Basil (October 1936). "Conversations with Rachmaninoff". Musical Opinion. 60: 14–15.

Midgette, Anne (1 December 2016). "Martha Argerich is a legend of the classical music world. But she doesn't act like one". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

Morrison, Bryce. One of Nature’s Happenings. Martha Argerich Rachmaninoff 3 with Riccardo Chailly. Liner notes. Philips Classics. 1995.

https://news.imz.at/industry-news/news/rachmaninoff-and-horowitz

Norris, Geoffrey (2001a). Rachmaninoff. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-16488-3.

"Program Notes: Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 3". Archived from the original on 2005-04-20. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

Ramachandran, Manoj; Aronson, Jeffrey K. (2006). "The diagnosis of art: Rachmaninov's hand span". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (10): 529–530. doi:10.1177/014107680609901015. PMC 1592053. PMID 17066567.

Robinson, Harlow (2007). Russians in Hollywood, Hollywood's Russians: Biography of an Image. Lebanon: University Press of New England. ISBN 978-1-555-53686-2.

Rubinstein, Arthur (1980). My Many Years. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-42253-8.

"Russia: Rachmaninoff reburial bid riles composer's family". BBC. 19 August 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

Scott, Michael (2011). Rachmaninoff. Cheltenham: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7242-3.

Seroff, Victor Ilyitch (1950). Rachmaninoff: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-836-98034-9.

Sylvester, Richard D. (2014). Rachmaninoff's Complete Songs: A Companion with Texts and Translations. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-2530-1259-3.

"The 20 Greatest Pianists of all time | Classical-Music.com". www.classical-music.com.

Wehrmeyer, Andreas (2004). Rakhmaninov. London: Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904341-50-5.

Yasser, Joseph (1951). "Progressive Tendencies in Rachmaninoff's Music". Tempo. 22 (22): 11–25. JSTOR 943073.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martha_Argerich

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symphony_No._1_(Rachmaninoff)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sergei_Rachmaninoff

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_Concerto_No._3_(Rachmaninoff)

![- Rachmaninoff: Complete RCA Recordings [Box Set] by Sony - Amazon.com Music - Rachmaninoff: Complete RCA Recordings [Box Set] by Sony - Amazon.com Music](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!HKdC!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F690adaf7-71f0-4af4-beab-66ea4f025dcb_225x225.jpeg)