Building a Collection #62

La Traviata

By Giuseppe Verdi

________________

Note: I apologize for the delay in publishing this week, I have been busy with several projects at once. Thank you for your patience and support.

I hope you are enjoying our journey through the 250 greatest classical music works of all-time as much as I am. The hit parade keeps coming, this time with Giuseppe Verdi’s ever popular opera La Traviata at #62. Verdi makes his third appearance on our list after his Requiem and the opera Rigoletto.

Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Verdi was born in 1813 in Le Roncole, Italy and died in 1901 in Milan, Italy. One of the greatest opera composers in history, Verdi perfected Italian opera, taking the genre to new heights dramatically and musically. Considered among the greats of opera alongside Mozart, Wagner, and Puccini, Verdi lives on in the many performances of his greatest works including his operas Rigoletto, La Traviata, Il Trovatore, Aida, Otello, Falstaff, and his Messa da Requiem.

Verdi showed early musical talent on the piano, and by the age of 15 had already begun composing. After the Milan Conservatory turned him away, he studied privately with several well-known teachers. In 1839, after moving full-time to Milan, he composed his first opera Oberto. Oberto was a success, but his second effort, Un giorno di regno, was a failure. Worse yet, after tragically losing his two children in previous years, his wife died leaving Verdi alone and depressed. In the immediate years after his wife’s death, Verdi attempted to rebound with the operas Nabucco, I Lombardi, Macbeth, and Luisa Miller in a series of moderately successful productions.

In the period 1851 through 1853, Verdi wrote three of his most popular operas, Il Trovatore, La Traviata, and Rigoletto. Although Il Trovatore and Rigoletto were immediate successes, La Traviata was not well-received initially. After some revisions, it too became a great success. For a time Verdi was involved in politics, and this became evident in his next works, Simon Boccanegra and Un Ballo in Maschera. By now he was well established as one of the greatest composers of his time, and the public eagerly awaited his new works. In the 1860s, Verdi composed La forza del destino and Don Carlos, both premiered in St. Petersburg.

Verdi moved permanently to Genoa, Italy and composed Aida in 1870, which was also a great success. But the composer gave up opera for a period of time thereafter, composing his String Quartet and Messa da Requiem in the 1870s. After a long opera gap, he turned out another opera in Otello in 1886 and then his final opera Falstaff in 1893. Falstaff, a bold and creative comic opera, became one of his greatest triumphs. In his final years, Verdi founded a hospital and a home for retired musicians. He retired to live at the Grand Hotel in Milan, composing his final work Quatro pezzi sacri (Four Sacred Pieces) published in 1897.

La Traviata

La Traviata (The Fallen Woman or The Woman Gone Astray) is an opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi set to an Italian libretto by Francesco Maria Piave. It is based on the play La Dame aux camélias (1852) by Alexandre Dumas fils. The opera was originally titled Violetta, after the main character. It was first performed on March 6, 1853 at La Fenice opera house in Venice. Although Verdi wanted the opera to be set in contemporary times, the production company of La Fenice insisted that it be set circa 1700. It was not until the 1880s that Verdi’s wishes for a more modern setting were honored.

Verdi was still working on Il Trovatore when he began work on La Traviata in 1852. Rigoletto, Il Trovatore, and La Traviata saw Verdi finding more intricate and colorful orchestration along with more mature melodic invention. With La Traviata, Verdi creates a more intimate sound world where his music strikes at the emotional core of the listener. By the time Verdi began working on Traviata, he had the luxury of being more particular about the story he chose. In this case he found inspiration in Dumas fils’ play La Dame aux camélias, which he decided would be titled La Traviata. Verdi wrote to a friend:

“For Venice I’m doing…La Traviata. A subject for our own age. Another composer wouldn’t have done it because of the costumes, the period and a thousand other silly scruples. But I’m writing it with the greatest of pleasures.”

The truth was Parisian society after the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars was diverse, with many newcomers to the French upper class. The age was marked by immoderation and indulgence, and even the middle class had opportunities never dreamed of previously. Prostitution became more common, and indeed was widely tolerated, at least in the cities. Employment options for lower class women were often dreadful and dangerous, and for a time prostitution was considered a safer and more profitable job than many other distasteful choices. But courtesans in Paris working for wealthy clientele endured the double-edged sword of living in relative lavishness while remaining nothing more than a piece of property to be used. It also tended to be a short and brutal life. There is evidence that Dumas based his play on an embellished true story of his own brief affair with a real courtesan, Marie Duplessis. Verdi and Piave toned down the less savory parts of the story quite a bit, and made the Duplessis character (Violetta) much more sympathetic, kinder, and more loving. The result is an idealized version of the main character, portraying her as a more complex and appealing role than either the novel or the play.

La Traviata’s premiere was a notorious failure, with the singers chosen for Violetta and Germont being in poor voice and unconvincing in the roles. Verdi made some revisions and that version was received better, also utilizing younger and more talented singers. Since then the work has gone on to become one of the best-loved operas in history.

The opera revolves around Violetta from beginning to end, so her role is the largest and most essential to the success of the performance. The demands of the role are substantial both vocally and dramatically. The opera gives Violetta music which pushes the extremes by exposing her vulnerability, frailty, and fiery personality in varying measures at different points in the story. She is given sweet and charming music at times, ebullient music at times, and ultimately heartbreaking music. Alfredo falls in love with her, and he is also given some of the most intimate and lyrical music in the opera. Germont, Alfredo’s father, is the third major character, and he goes through a transformation in the story to eventually understand that Alfredo’s love for Violetta is genuine.

Here is the synopsis of the opera, as published by the Metropolitan Opera:

ACT I

Violetta Valéry knows that she will die soon, exhausted by her restless life as a courtesan. At a party she is introduced to Alfredo Germont, who has been fascinated by her for a long time. Rumor has it that he has been enquiring after her health every day. The guests are amused by this seemingly naïve and emotional attitude, and they ask Alfredo to propose a toast. He celebrates true love, and Violetta responds in praise of free love (Ensemble: Libiamo ne’ lieti calici). She is touched by his candid manner and honesty. Suddenly she feels faint, and the guests withdraw. Only Alfredo remains behind and declares his love (Duet: Un dì felice). There is no place for such feelings in her life, Violetta replies. But she gives him a camellia, asking him to return when the flower has faded. He realizes this means he will see her again the following day. Alone, Violetta is torn by conflicting emotions—she doesn’t want to give up her way of life, but at the same time she feels that Alfredo has awakened her desire to be truly loved (Ah, fors’è lui… Sempre libera).

ACT II

Violetta has chosen a life with Alfredo, and they enjoy their love in the country, far from society (De’ miei bollenti spiriti). When Alfredo discovers that this is only possible because Violetta has been selling her property, he immediately leaves for Paris to procure money. Violetta has received an invitation to a masked ball, but she no longer cares for such distractions. In Alfredo’s absence, his father, Giorgio Germont, pays her a visit. He demands that she separate from his son, as their relationship threatens his daughter’s impending marriage (Duet: Pura siccome un angelo). But over the course of their conversation, Germont comes to realize that Violetta is not after his son’s money—she is a woman who loves unselfishly. He appeals to Violetta’s generosity of spirit and explains that, from a bourgeois point of view, her liaison with Alfredo has no future. Violetta’s resistance dwindles and she finally agrees to leave Alfredo forever. Only after her death shall he learn the truth about why she returned to her old life. She accepts the invitation to the ball and writes a goodbye letter to her lover. Alfredo returns, and while he is reading the letter, his father appears to console him (Di Provenza). But all the memories of home and a happy family can’t prevent the furious and jealous Alfredo from seeking revenge for Violetta’s apparent betrayal.

At the masked ball, news has spread of Violetta and Alfredo’s separation. There are grotesque dance entertainments, ridiculing the duped lover. Meanwhile, Violetta and her new lover, Baron Douphol, have arrived. Alfredo and the baron battle at the gaming table and Alfredo wins a fortune: lucky at cards, unlucky in love. When everybody has withdrawn, Alfredo confronts Violetta, who claims to be truly in love with the Baron. In his rage Alfredo calls the guests as witnesses and declares that he doesn’t owe Violetta anything. He throws his winnings at her. Giorgio Germont, who has witnessed the scene, rebukes his son for his behavior. The baron challenges his rival to a duel.

ACT III

Violetta is dying. Her last remaining friend, Doctor Grenvil, knows that she has only a few more hours to live. Alfredo’s father has written to Violetta, informing her that his son was not injured in the duel. Full of remorse, he has told him about Violetta’s sacrifice. Alfredo wants to rejoin her as soon as possible. Violetta is afraid that he might be too late (Addio, del passato). The sound of rampant celebrations are heard from outside while Violetta is in mortal agony. But Alfredo does arrive and the reunion fills Violetta with a final euphoria (Duet: Parigi, o cara). Her energy and exuberant joy of life return. All sorrow and suffering seems to have left her—a final illusion, before death claims her.

Recommended Recordings

As a generalization, the quality and quantity of opera recordings has declined over the years, and there is some consensus that we are well past the glory days of opera recordings. This is mitigated somewhat by the availability of video recordings and live streaming, but now we are in a period where fewer record companies and producers are willing to spend the time and money needed to make great opera. We can argue the point, but in my opinion the performances of core opera repertoire that have been recorded in recent decades, with some exceptions, are not up to the standard of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

Such is the case with La Traviata. It is true there have been some memorable Violettas fairly recently such as Angela Gheorghiu, Renee Fleming, and Ermonela Jaho. But even so, I would not put them in the same league as Maria Callas, Joan Sutherland, Ileana Cotrubas, or Anna Moffo when it comes to famous Violettas. Callas in particular simply owned the role, just as she did with Norma and Tosca. Sutherland and Moffo both brought distinct characterizations (although Sutherland’s vocal acting pales next to Callas), and both were given better sound than Callas.

Because Callas’ finest recordings of La Traviata are from live performances, and all from the 1950s, we must contend with the subject of sound quality. It is a pity there is no Callas recording of La Traviata in good sound. Nevertheless, the artistic value she brought to Violetta is priceless and in my view transcends the sonic deficits of those live recordings. They are all important to her legacy. If you must have modern sound, that is understandable, but you will miss one of the greatest interpreters of Violetta on record.

The tenor role of Alfredo and the baritone role of Germont are also important to the mix, though to a lesser degree than Violetta. Still, Alfredo must deliver the goods and the role requires sensitivity, lyricism, and moderate power. Germont must be steady of voice and emotionally involved to be effective.

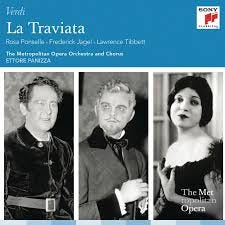

The first recommended recording of La Traviata is an historical one from 1935 on Sony Classical with the soprano Rosa Ponselle as Violetta, Frederick Jagel as Alfredo, and the famous baritone Lawrence Tibbett as Germont. The recording features the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus under the baton of Ettore Panizza, and was taken from a live broadcast. As you might imagine with a live recording from 1935, the sound is poor with a good amount of hiss. But the reason this is recommended is the amazing Rosa Ponselle and her remarkably fluid and versatile voice. This is one of the great portrayals of Violetta, even with the sound limitations. The baritone of Lawrence Tibbett is a joy as well, and he is well paired with Ponselle. Jagel’s singing of Alfredo is solid, if not quite as remarkable. I like the way Panizza conducts the score, this is old style Verdi full of energy, faster tempos, and comes directly from Verdi’s own indications on the score. The Naxos version includes the radio broadcast commentary, which is interesting in itself. But the Sony version is a better transfer of the music.

Legendary Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini knew Giuseppe Verdi well, and in fact studied Verdi’s scores with the composer. Therefore, there are those purists that argue Toscanini’s interpretations of Verdi’s works are the most authentic and perhaps the closest we shall hear to what Verdi intended. I don’t know if that is accurate, but I know I prefer Toscanini’s quicker and more direct way with La Traviata to the slower, melodramatic style that would dominate later. Toscanini’s 1946 live radio broadcast from NBC studios on RCA (and in even better sound on the Prinstine label) with the NBC Symphony Orchestra & Chorus with soprano Licia Albanese, tenor Jan Peerce, and baritone Robert Merrill is something very special. If you listen to the Ponselle recording from 1935, you will notice a significant improvement in sound quality here. This is not in modern sound by any means, but everything can be heard and enjoyed. The Music & Arts label put out a recording of the dress rehearsal of this performance (available on Spotify), and some believe it is even more electric than the RCA version. Albanese is a wonderful vocal actress and can hit all the notes, although she does project a matronly air which is not quite convincing for the role, but this is not a major objection. On the other hand, Peerce as Alfredo is completely convincing in the role, and has an endearing tone. I enjoy him more on this recording than anywhere else I’ve heard him, even if at times he lacks subtlety in his tone. Merrill rises to the occasion of singing under Toscanini, bringing a full tone and becoming more involved than usual in his role.

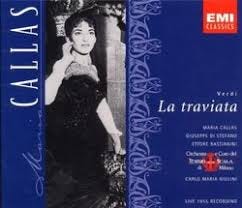

Let’s get to the recordings of La Traviata which feature the great Maria Callas as Violetta. She recorded the role at least four times, but it is her last three recordings, all recorded live, which show her in the best voice and display the most depth in her interpretation of the role. The 1955 live recording under Carlo Maria Giulini with the Teatro alla Scala Orchestra and Chorus on Warner/EMI also features tenor Giuseppe di Stefano and baritone Ettore Bastianini. Callas is near her vocal prime here, and given that she performed the role of Violetta 63 times (only exceeded by the role of Norma, which she sang 92 times), she knew the role inside and out. While the sound is acceptable, it has moments of harsh and overloaded sound and other moments where the singers move away from the microphones where the principals are not captured well. But the performance itself is one of the finest, with Callas showing vulnerability and frailty in her voice, but also highlighting her trademark, piercing high register which listeners either love or hate (I love it). The uniqueness of her voice suits the role of Violetta well, and no other soprano has ever gotten inside the role so thoroughly. She is emotionally and vocally convincing. Di Stefano is also near his prime, and so I have no complaints about his voice per se. His interpretation is lacking some depth in terms of subtlety and imagination (I prefer Valletti’s more lyrical approach on the Monteux recording and on the Covent Garden set with Callas), but there is no question he is impressive. Bastianini is a superb Germont, one of the best on record. Giulini’s direction is intelligent and dramatic.

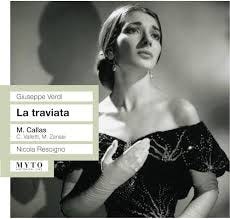

Sticking with Maria Callas again, her 1958 live mono recording with conductor Nicola Rescigno in London at Covent Garden with the Covent Garden Orchestra and Chorus, on the MYTO and IDIS labels and on streaming services. Callas is joined by tenor Cesare Valletti as Alfredo and baritone Mario Zanasi as Germont. For me, this is the all-around best La Traviata recording with Maria Callas, even if I have some of the same reservations about the live sound. A bit of unsteadiness and screech has crept into Callas’ upper range, but this is an insignificant point when you consider her sensitive interpretation and heroic performance. Valletti is nearly ideal in my mind for the role of Alfredo, youthful sounding, lovely and consistent in tone with all the notes securely dispatched, and with an appealing Italianate style. He is certainly more nuanced and sensitive than Di Stefano or Peerce, and while he is marginally more steady in Monteux’s studio set, he is more exciting here. Zanasi is somewhat similar to Bastianini in that his fatherly portrayal is not dark and deep but rather youngish sounding. This is not ideal for the role, but his singing is wonderful. Rescigno clearly slows some tempi to give Callas room to breathe and expand, but overall his direction is sensible and idiomatic.

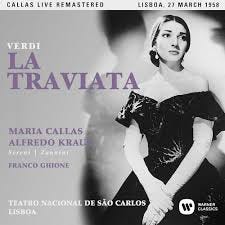

The other live recording with Maria Callas is her 1958 Lisbon Traviata under Franco Ghione with the Teatro Nacional São Carlos Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional and Chorus joined by tenor Alfredo Kraus and baritone Mario Sereni. This is also valuable for being another wonderful Callas’ interpretation, though I like Valletti’s voice better than Kraus’ voice and Sereni is a bit bland and faceless. The sound is marginally better than the London set, though there remain some imperfections and distractions. But truth be told there is not much to choose between this recording and the Covent Garden.

One surprise for me in putting together this survey was the 1956 La Traviata recording directed by French conductor Pierre Monteux from Rome on RCA/Sony with the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma Orchestra and Chorus. Violetta is played by soprano Rosanna Carteri (completely unknown to me), Alfredo is sung by Cesare Valletti, and Germont is sung by Leonard Warren. I was surprised because Monteux conducted relatively few operas, and while it is true his tempos are slow, there is a beauty and arc throughout which emphasizes the romantic nature of the story…this is at the opposite end from Toscanini’s quicker and more direct approach. Another pleasant surprise is Carteri’s Violetta, she is an almost ideal partner with Valletti, and they blend quite well. Carteri has a deeper, more resonant tone than Callas, but also easily negotiates Violetta’s more daring passages with an impressive range and smoothness. She doesn’t bring the same intensity to the role as Callas, but nobody does. Her portrayal is more than satisfying. Valletti is again very impressive, passionate but controlled with such a lovely tone to his voice. Warren is appropriately paternal in tone, and he brings a dramatic flourish with his vocal acting; he can be harsh when needed, but also more tender towards the end. The sound in the Sony remastering is very good, with just a small amount of hiss. Certainly a version to consider.

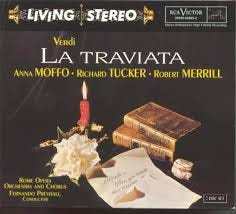

The RCA Living Stereo series got into the opera business as well, and their recording techniques were state-of-the-art at the time. The 1960 Living Stereo La Traviata features Anna Moffo as Violetta, Richard Tucker as Alfredo, and Robert Merrill as Germont, with Fernando Previtali conducting the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma Orchestra and Chorus. This is a studio recording, and the sound is very good for its time. Moffo is in her prime with a youthful and nimble presence which checks all the boxes. Moffo reminds me here of Leontyne Price in the most positive way, because Moffo has a depth in her voice which includes a legitimate “chest-voice” for lower notes. This comes with a tendency to “scoop” notes (though not nearly as much as Price did later in her career), but this is not bothersome. Moffo is fully in character, hits all the notes, and while not quite as dramatic as Callas, she is not far behind and some may prefer her tone to the more shrill Callas. While I enjoy Tucker’s voice, I don’t think he is quite right for the role because his tone tends to be loud, unsubtle, and not particularly youthful sounding, but there is no doubting his prowess. Merrill as Germont is more satisfying, and this was one of his best roles. Previtali prioritizes the musical line and the lyricism of the score, and his tempos are leisurely to middle-of-the-road. He is able to vary dynamics and tempos for the inherent drama in the music, and never goes over the top. This is a satisfying choice to be sure.

American soprano Beverly Sills became something of an opera legend in her heyday of the 1960s and 1970s after becoming a child star thanks to her appearances on TV at a young age. In her prime she was one of the best coloratura sopranos around, and Violetta was one of her signature roles. Her 1971 recording on EMI/Warner with tenor Nicolai Gedda and baritone Rolando Panerai. The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and John Alldis Choir is led by Aldo Ceccato. Sills is in excellent voice, and she moves effortlessly up and down the range. Her characterization of the role rivals Callas and Cotrubas, and her top notes are as thrilling as you will find anywhere. Gedda is capable of a softer and more sensitive tone, and it is in those romantic scenes where he shines. Still, Gedda is an acquired taste and I prefer a tenor like Valletti who can be more authentically Italianate in tone. Panerai is better than average as Germont in terms of taking on the role expressively and convincingly. I was not familiar with Ceccato, but he and the RPO are unobtrusive and the sound is good. This is primarily recommended for Bevery Sills’ beautiful Violetta.

Skipping ahead to 1976, we encounter arguably the greatest conductor of the twentieth century, Carlos Kleiber, conducting the Bayerisches Staatsorchester and Bayerische Staatsoper Chorus joined by soprano Ileana Cotrubas, tenor Placido Domingo, and baritone Sherrill Milnes, vividly recorded by Deutsche Grammophon. Domingo and Milnes are solidly fine, and while they are not exceptional, they are more than adequate. The highlights of this set for me are Cotrubas and Kleiber. Cotrubas delivers a stunning and masterful performance as Violetta, especially so when it comes to her frailty and vulnerability. She had a natural tenderness and exposed quality in her voice that she uses to perfection here, while she still brings all the vocal fireworks needed. While not as frantically intense as Callas, Cotrubas’ performance is a truly great interpretation in my book. I have the utmost respect for Kleiber, and he once again shows why he was a cut above the rest. His instincts are right on when it comes to the speeding up and slowing down in tempo, and he shows a sensitivity to the drama which is only equaled by Giulini, Toscanini, and Monteux. The sound is excellent.

The legendary soprano Joan Sutherland was one of the finest coloratura sopranos in history (coloratura being the ability to use elaborate ornamentation in singing). She recorded Violetta twice, and it is her second recording from 1980 on Decca that makes the recommended list. Sutherland is joined by legendary tenor Luciano Pavarotti as Alfredo and baritone Matteo Manuguerra as Germont, and the National Philharmonic Orchestra and London Opera Chorus is conducted by Richard Bonynge. The pervasive criticism of Sutherland’s singing was that her diction was poor, and that was often true. She prioritized the roundness of her tone rather than words per se, and this also sometimes meant that her characterization of the role was not as affecting. This is true of her Violetta here as well, but Sutherland did possess a unique voice and a remarkable virtuosic ability which made her interpretation special. While she sounds a bit too matronly on this recording, she is more dramatically inclined than on other recordings, and she is particularly effective in the final act. While she does not approach Callas, Moffo, or Cotrubas in her vocal acting, she does deliver some lovely singing. Pavarotti was never known for his acting, so while there is some lack of nuance and subtlety in his Alfredo, his golden tone is appealing and he is in his prime vocally. Manuguerra is one of the most successful Germonts on record, he is very convincing in the role, and his voice fits nicely. Bonynge is reliably faithful to the score, and the sound has good resonance and detail.

My favorite more recent recording is from soprano Angela Gheorghiu on the 1994 live recording on Decca led by Sir Georg Solti with the Covent Garden Orchestra and Chorus in London. Alfredo is sung by Frank Lopardo, and Germont is sung by Leo Nucci. Gheorghiu has a splendid voice, and she is easily believable as Violetta. Only 29 at the time of this recording, she was in her prime and was able to bring both powerful emotion and a sharp edge to her tone when needed. I would say Gheorghiu and Solti’s sympathetic direction are the strengths of the set, and it is recommended on that alone. Even so, I would not put Gheorghiu on the same level as Callas, Moffo, Cotrubas, or even Sills. Lopardo’s tenor is somewhat underpowered and has a pinched quality to his voice which is not too appealing. Nucci is average at best, but at least he doesn’t detract from Gheorghiu’s wonderful performance. The sound is very good, so if you need a Traviata in modern sound, this is a solid choice.

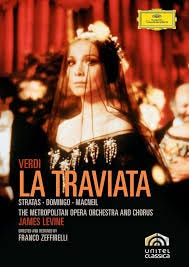

I wanted to include a recording of La Traviata with Teresa Stratas as Violetta, but the best recording (on video) with Placido Domingo and Cornell Macneil from the Met with James Levine on DG is behind a paywall, and I don’t own the DVD. The individual clips of highlights from that set on YouTube sound very good. Stratas’ 1965 recording on Orfeo with Fritz Wunderlich and Hermann Prey is sadly not recommendable.

Honorable Mention

RAI Torino / Maria Callas / Gabriele Santini (Warner 1953)

Maggio Musicale Fiorentino / Joan Sutherland / John Pritchard (Decca 1962)

La Scala / Renata Scotto / Antonino Votto (DG 1962)

RCA Italiana / Montserrat Caballé / Georges Prêtre (RCA 1967)

Metropolitan Opera / Cheryl Studer / James Levine (DG 1991)

I have not fully sampled more recent recordings, so this list may be incomplete to some degree. I admit to my own bias of preferring mostly older recordings, at least for this opera. But I hope you will take the opportunity to hear some of the classic recordings listed above, and if you have any favorite recordings made more recently, send me a message!

Join me next time when we discuss Igor Stravinsky’s ballet Petrushka (Petrouchka). See you then!

_______________

Notes:

Kimbell, David (2001). Holden, Amanda (ed.). The New Penguin Opera Guide. New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 978-0-14-029312-8.

Moore, Ralph. A partial survey of recordings of Verdi’s La traviata. MusicWeb International. Online at https://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2021/Jul/Verdi-traviata-survey.htm.

Youens, Susan. Program Note. Verdi La Traviata. The Metropolitan Opera Playbill. April 2019.